|

CHAPTER II - pg. 28

The two Strangers

- The Circus Company

- Departures from Saratoga

- Ventriloquism and Legerdemain

- Journey to New York

- Free Papers

- Brown and Hamilton

- The haste to reach the Circus

- Arrival in Washington

- Funeral of Harrison

- The Sudden Sickness

- The Torment of Thirst

- The Receding Light

- Insensibility

- Chains and Darkness

ONE morning,

towards the latter part of the month of March, 1841,

having at that time no particular business to engage my

attention, I was walking about the village of Saratoga

Springs, thinking to myself where I might obtain some

present employment, until the busy season should arrive.

Anne, as was her usual custom, had gone over to

Sandy Hill, a distance of some twenty-miles, to take

charge of the culinary department at Sherrill's Coffee

House, during the session of the court.

Elizabeth, I think, had accompanied her.

Margaret and Alonzo were with their aunt at

Saratoga.

On the corner of Congress the street and Broadway, near

the tavern, then, and for aught I know to the contrary,

still kept by Mr. Moon, I was met by two

gentlemen of respectable appearance, both of whom were

entirely unknown to me. I have the impres-

[pg. 29]

TWO STRANGERS.

sion that they were introduced to me by

some one of my acquaintances, but who, I have in vain

endeavored to recall, with the remark that I was an

expert player on the violin.

At any rate, they immediately entered into conversation

on that subject, making numerous inquiries touching my

proficiency in that respect. My responses being to

all appearances satisfactory, they proposed to engage my

services for a short period, stating, at the same time,

I was just such a person as their business required.

Their names, as they afterwards gave them to me, were

Merrill Brown and Abram Hamilton, though

whether these were their true appellations, I have

strong reasons to doubt. The former was a man

apparently forty years of age, somewhat short and

thick-set, with a countenance indicating shrewdness and

intelligence. He wore a black frock coat and black

hat, and said he resided either at Rochester or at

Syracuse. the latter was a young man of fair

complexion and light eyes, and, I should judge, had not

passed the age of twenty-five. He was tall and

slender , dressed in a snuff-colored coat, with glossy

hat, and vest of elegant pattern. His whole

apparel was in the extreme of fashion. His

appearance was somewhat effeminate, but prepossessing,

and their was about him an easy air, that showed he had

mingled with the world. They were connected, as

they informed me, with a circus company, then in the

city of Washington; that they were on their

[pg. 30]

way thither to rejoin it, having left it for a short

time to make an excursion northward, for the purpose of

seeing the country, and were paying their expenses by an

occasional exhibition. They also remarked that

they had found much difficulty in procuring music for

their entertainments, and that if I would accompany them

as far as New-York, they would give me one dollar for

each day's services, and three dollars in addition for

every night I played at their performances, besides

sufficient to pay the expenses of my return from

New-York to Saratoga.

I at once accepted the tempting offer, both for the

reward it promised, and from the desire to visit the

metropolis. They were anxious to leave

immediately. Thinking my absence would brief, I

did not deem it necessary to write to Anne

whither I had gone; in fact supposing that my return,

perhaps, would be as soon as hers. So taking a

change of linen and my violin, I was ready to depart.

The carriage was brought round - a covered one, drawn by

a pair of noble bays, altogether forming an elegant

establishment. Their baggage, consisting of three

large trunks, was fastened on the rack, and mounting to

the driver's seat, while they took their places in the

rear, I drove away from Saratoga on the road to Albany,

elated with my new position, and happy as I had ever

been, on any day in all my life.

We passed through Ballston, and striking the ridge

road, as it was called, if my memory correctly serves

[pg. 31]

VENTRILOQUISM AND LEGERDEMAIN.

me, followed it direct to Albany.

We reached that city before dark, and stopped at a hotel

southward from the Museum.

This night I had an opportunity of witnessing one of

their performances - the only one, during the whole

period I was with them. Hamilton was

station at the door; I formed the orchestra, while

Brown provided the entertainment. It consisted

in throwing balls, dancing on the rope, frying pancakes

in a hat, causing invisible pigs to squeal, and other

like feats of ventriloquism and legerdemain. The

audience was extraordinarily sparse, and not of the

selectest character at that, and Hamilton's

report of the proceeds presented but a "Beggerly account

of empty boxes."

Early next morning we renewed our journey. The

burden of their conversation now was the expression of

an anxiety to reach the circus without delay. They

hurried forward, without again stopping to exhibit, and

in due course of time, we reached New York, taking

lodgings at a house on the west side of the city, in a

street running from Broadway to the river. I

supposed my journey was at an end, and expected in a day

or two at least, to return to my friends and family to

Saratoga. Brown and Hamilton,

however, began to importune me to continue with them to

Washington. They alleged that immediately on their

arrival, now that the summer season was approaching, the

circus would set out for the north. They promised

me a situation and high wages if I

[pg. 32]

would accompany them. Largely did they expatiate

on the advantages that would result to me, and such were

the flattering representations they made, that I finally

concluded to accept the offer.

The next morning they suggested that, inasmuch as we

were about entering a slave State, it would be well,

before leaving New York, to procure free papers.

The idea struck me as a prudent one, though I think it

would scarcely have occurred to me, had they not

proposed it. We proceeded at once to what I

understood to be the Custom House. They made oath

to certain facts showing I was a free man. A paper

was drawn up an handed us, with the direction to take it

to the clerk's office. We did so, and the clerk

having added something to it, for which he was paid six

shillings, we returned again to the Custom House.

Some further formalities were gone through with before

it was completed, when, paying the officer two dollars,

I placed the papers in my pocket, and started with my

two friends to our hotel. I thought at the time, I

must confess, that the papers were scarcely worth the

cost of obtaining them - the apprehension of danger to

my personal safety never having suggested itself to me

in the remotest manner. The clerk, to whom we were

directed, I remember, made a memorandum in a large book,

which, I presume, is in the office yet. A

reference to the entries during the latter part of

March, or first of April, 1841, I have no doubt will

satisfy the incredulous, at least so far as this

particular transaction is concerned.

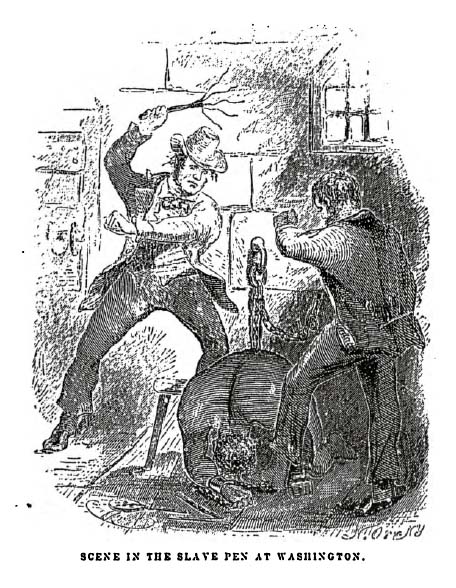

SCENE IN THE SLAVE PEN AT WASHINGTON

[pg. 33]

ARRIVAL AT WASHINGTON

With the

evidence of freedom in my possession, the next day after

our arrival in New York, we crossed the ferry to Jersey

City, and took the road to Philadelphia. Here we

remained one night, continuing our journey towards

Baltimore early in the morning. In due time, we

arrived in the latter city, and stopped at a hotel near

the railroad depot, either kept by a Mr. Rathbone

or known as the Rathbone House. All the way

from New York, their anxiety to reach the circus seemed

to grow more and more intense. We left the

carriage at Baltimore, and entering the cars, proceeded

to Washington, at which place we arrived just at

nightfall, the evening previous to the funeral of

General Harrison, and stopped at Gadsby's

Hotel, on Pennsylvania Avenue.

After supper they called me to their apartments, and

paid me forty-three dollars, a sum greater than my wages

amounted to, which act of generosity was in consequence,

they said, of their not having exhibited as often as

they had given me to anticipate, during our trip from

Saratoga. They moreover informed me that it had

been the intention of the circus company to leave

Washington the next morning, but that on account of the

funeral, they had concluded to remain another day.

They were then, as they had been from the time of our

first meeting, extremely kind. No opportunity was

omitted of addressing me in the language of approbation;

while, on the other hand, I was certainly much

prepossessed in their favor. I

[pg. 34]

gave them my confidence without reserve, and would

freely have trusted them to almost any extent.

Their constant conversation and manner towards me -

their foresight in suggesting the idea of free papers,

and a hundred other little acts, unnecessary to be

repeated - all indicated that they were friends indeed,

sincerely solicitous for my welfare. I know not

but they were. I know not but they were innocent

of the great wickedness of which I now believe them

guilty. Whether they were accessory to my

misfortunes - subtle and inhuman monsters in the shape

of men - designedly luring me away from home and family,

and liberty, for the sake of gold - those who read these

pages will have the same means of determining as myself.

If they were innocent, my sudden disappearance must have

been unaccountable indeed; but revolving in my mind all

the attending circumstances, I never yet could indulge,

towards them, so charitable a supposition.

After receiving the money from them, of which they

appeared to have an abundance, they advised me not to go

into the streets that night, inasmuch as I was

unacquainted with the customs of the city.

Promising to remember their advice, I left them

together, and soon after was shown by a colored servant

to a sleeping room in the back part of the hotel, on the

ground floor. I laid down to rest, thinking of

home and wife, and children, and the long distance that

stretched between us, until I fell asleep. But

[pg. 35]

FUNERAL OF HARRISON.

no good angel of pity came to my

bedside, bidding me to fly - no voice of mercy

forewarned me in my dreams of the trials that were just

at hand.

The next day there was a great pageant in Washington.

The roar of cannon and the tolling of bells filled the

air, while many houses were shrouded with crape, and the

streets were black with people. As the day

advanced, the procession made its appearance, coming

slowly through the Avenue, carriage after carriage, in

long succession, while thousands upon thousands followed

on foot - all moving to the sound of melancholy music.

They were bearing the dead body of Harrison to

the grave.

From early in the morning, I was constantly in the

company of Hamilton and Brown. They

were the only persons I knew in Washington. We

stood together as the funeral pomp passed by. I

remember distinctly how the window glass would break and

rattle to the ground, after each report of the cannon

they were firing in the burial ground. We went to

the capitol, and walked a long time about the grounds.

In the afternoon, they strolled towards the President's

House, all the time keeping me near to them, and

pointing out various places of interest. As yet, I

had seen nothing of the circus. In fact, I had

thought of it but little, if at all, amidst the

excitement of the day.

My friends, several times during the afternoon, entered

drinking saloons, and called for liquor. They were

by no means in the habit, however, so far as I

[pg. 36]

knew them, of indulging to excess. On these

occasions, after serving themselves, they would pour out

a glass and hand it to me. I did not become

intoxicated, as may be inferred from what subsequently

occurred. Towards evening, and soon after

partaking of one of these potations, I began to

experience most unpleasant sensations. I felt

extremely ill. My head commenced aching - a dull, heavy

pain, inexpressibly disagreeable. At the supper

table, I was without appetite; the sight and flavor of

food was nauseous. About dark the same servant

conducted me to the room I had occupied the previous

night. Brown and Hamilton advised me

to retire, commiserating me kindly, and expressing hopes

that I would be better in the morning. Divesting

myself of coat and boots merely, I threw myself upon the

bed. It was impossible to sleep. The pain in

my head continued to increase, until it became almost

unbearable. In a short time I became thirsty.

My lips were parched. I could think of nothing but

water - of lakes and flowing rivers, of brooks where I

had stopped to drink, and of the dripping bucket, rising

with its cool and overflowing nectar, from the bottom of

the well. Towards midnight, as near as I could

judge, I arose, unable longer to bear such intensity of

thirst. I was a stranger in the house, and knew

nothing of its apartments. There was no one up, as

I could observe. Groping about at random, I knew

not where, I hound the way at last to a kitchen in the

basement. Two or three colored servants were

moving through it, one

[pg. 37]

THE TORMENT OF THIRST.

of whom, a woman, gave me two glasses of

water. It afforded momentary relief, but by the

time I had reached my room again, the same burning

desire of drink, the same tormenting thirst, had again

returned. If was even more torturing than before,

as was also the wild pain in my head, if such a thing

could be. I was in sore distress - in most

excruciating agony! I seemed to stand on the brink

of madness! The memory of that night of horrible

suffering will follow me to the grave.

In the course of an hour or more after my return from

the kitchen, I was conscious of some one entering my

room. There seemed to be several - a mingling of

various voices, - but how many, or who they were, I

cannot tell. Whether Brown and Hamilton

were among them, is a mere matter of conjecture. I

only remember, with any degree of distinctness, that I

was told it was necessary to go to a physician and

procure medicine, and that pulling on my boots, without

coat or hat, I followed them through a long passage-way,

or alley, into the open street. It ran out at

right angles from Pennsylvania Avenue. On the

opposite side there was a light burning in a window.

My impression is there were then three persons with me,

but it is altogether indefinite and vague, and like the

memory of a painful dream. Going towards the

light, which I imagined proceeded from a physician's

office, and which seemed to recede as I advanced, is the

last glimmering recollection I can now recall.

From that moment I was

[pg. 38]

insensible. How long I remained in that condition

- whether only at night, or many days and nights - I do

not know; but when consciousness returned, I found

myself alone, in utter darkness, and in chains.

The pain in my head had subsided in a measure, but I

was very faint and weak. I was sitting upon a low

bench, made of rough boards, and without coat or hat.

I was hand-cuffed. Around my ankles also were a

pair of heavy fetters. One end of a chain was

fastened to a large ring in the floor, the other to the

fetters on my ankles. I tried in vain to stand

upon my feet. Waking from such a painful trance,

it was some time before I could collect my thoughts.

Where was I? What was the meaning of these chains?

Where were Brown and Hamilton? What

had I done to deserve imprisonment in such a dungeon?

I could not comprehend. There was a blank of some

indefinite period, preceding my awakening in that

lonely place, the events of which the at most stretch of

memory was unable to recall. I listened intently

for some sign or sound of life, but nothing broke the

oppressive silence, save the clinking of my chains,

whenever I chanced to move. I spoke aloud, but the

sound of my voice startled me. I felt of my

pockets, so far as the fetters would allow - far enough,

indeed , to ascertain that I had not only been robbed of

liberty, but that my money and free papers were also

gone! Then did the idea begin to break upon my

mind, at first dim and confused, that I had been

kidnapped. But that I thought was incredible.

[pg. 39]

CHAINS AND DARKNESS.

There must have been some

misapprehension - some unfortunate mistake. It

could not be that a free citizen of New York, who had

wronged no man, nor violated any law, should be dealt

with thus inhumanly. The more I contemplated my

situation, however, the more I became confirmed in my in

my suspicions. It was a desolate thought, indeed.

I felt there was no trust or mercy in unfeeling man; and

commending myself to the God of the oppressed, bowed my

head upon my fettered hands, and wept most bitterly.

<

BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS > |