CHAPTER VIII

Pg. 105

- Ford's Embarrassments

- Mistress Ford's Plantation on Bayou Boeuf

- Description of the Latter

- Ford's Brother-in-law, Peter Tanner

- Meeting with Eliza

- She still Mourns for her Children

- Ford's Overseer, Chapin

- Tibeats' Abuse

- The Keg of Nails

- The First Fight with Tibeats

- His Discomfiture and Castigation

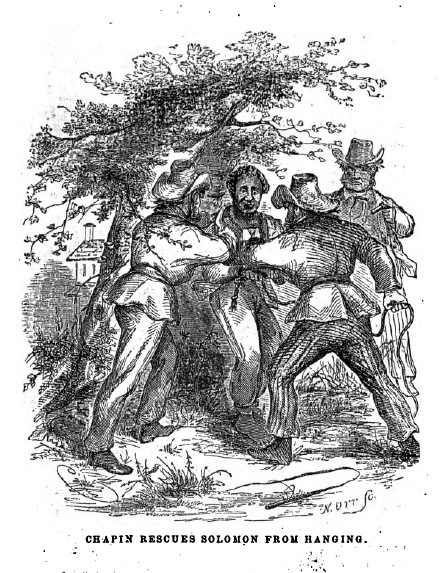

- The attempt to Hang me

- Chapin's Interference and Speech

- Unhappy Reflections

- Abrupt Departure of Tibeats, Cook, and

Ramsey

- Lawson and the Brown Mule

- Message to the Pine Woods

WILLIAM FORD unfortunately became embarrassed in

his pecuniary affairs. A heavy judgment was

rendered against him in consequence of his having

become security for his brother, Franklin Ford,

residing on Red River, above Alexandria, and who had

failed to meet his liabilities. He was also

indebted to John M. Tibeats to a considerable

amount in consideration of his services in building

the mills on Indian Creek, and also a weaving-house,

corn-mill and other erections on the plantation at

Bayou Boeuf, not yet completed. It was

therefore necessary, in order to meet these demands,

to dispose of eighteen slaves, myself among the

number. Seventeen of them, including Sam

and Harry, were purchased by Peter

Compton, a planter also residing on Red River.

[pg. 106]

I was sold to Tibeats, in consequence,

undoubtedly, of my slight skill as a carpenter.

This was in the winter of 1842. The deed of

myself from Freeman to Ford, as I

ascertained from the public records in New-Orleans

on my return, was dated June 23d, 1841. At the

time of my sale to Tibeats, the price agreed

to be given for me being more than the debt, Ford

took a chattel mortgage of four hundred dollars.

I am indebted for my life, as will hereafter be

seen, to that mortgage.

I bade farewell to my good friends at the opening, and

departed with my new master Tibeats. We

went down to the plantation on Bayou Boeuf, distant

twenty-seven miles from the Pine Woods, to complete

the unfinished contract. Bayou Boeuf is a

sluggish, winding stream - one of those stagnant

bodies of water common in that region, setting back

from Red River. It stretches from a point not

far from Alexandria, in a south-easterly directions,

and following its tortuous course, is more than

fifty miles in length. Large cotton and sugar

plantations line each shore, extending back to the

borders of interminable swamps. It is alive

with aligators, rendering it unsafe for

swine, or unthinking slave children to stroll along

its banks. Upon a bend in this bayou, a short

distance from Cheneyville, was situated the

plantation of Madam Ford - her

brother, Peter Tanner, a great landholder,

living on the opposite side.

On my arrival at Bayou Boeuf, I had the pleasure of

meeting Eliza, whom I had not seen for

several

[pg. 107]

months. She had not pleased Mrs. Ford,

being more occupied in brooding over her sorrows

than in attending to her business, and had, in

consequence, been sent down to work in the field on

the plantation. She had grown feeble and

emaciated, and was still mourning for her children.

She asked me if I had forgotten them, and a great

many times inquired if I still remembered how

handsome little Emily was - how much

Randall loved her - and wondered if they were

living still, and where the darlings could then be.

She had sunk beneath the weight of an excessive

grief. Her drooping form and hollow cheeks too

plainly indicated that she had well nigh reached the

end of her weary road.

Ford's overseer on this plantation, and who had

the exclusive charge of it, was a Mr. Chapin,

a kindly-disposed man, and a native of Pennsylvania.

In common with others, he held Tibeats in

light estimation, which fact, in connection with the

four hundred dollar mortgage, was fortunate for me.

I was now compelled to labor very hard. From

earliest dawn until late at night, I was not allowed

to be a moment idle. Notwithstanding which,

Tibeats was never satisfied. He was

continually cursing and complaining. He never

spoke to me a kind word. I was his faithful

slave, and earned him large wages every day, and yet

I went to my cabin nightly, loaded with abuse and

stinging epithets.

We had completed the corn mill, the kitchen, and so

forth, and were at work upon the weaving-house,

[pg. 108]

when I was guilt of an act, in that State punishable

with death. It was my first fight with

Tibeats. The weaving-house we were

erecting stood in the orchard a few rods from the

residence of Chapin, or the "great house," as

it was called. One night having worked

until it was too dark to see, I was ordered by

Tibeat to rise very early in the morning,

procure a keg o nails form Chapin, and

commence putting on the clapboards. I retired

to the cabin extremely tired, and having cooked a

supper of bacon and corn cake, and conversed a while

with Eliza, who occupied the same cabin, as

also did Lawson and his wife Mary, and

a slave named Bristol, laid down upon the

ground floor, little dreaming of hte sufferings that

awaited me on the morrow. Before daylight I

was on the piazza of the "great house," awaiting the

appearance of overseer Chapin. To have

aroused him from his slumbers and stated my errand,

would have been an unpardonable boldness. At

length he came out. Taking off my hat, I

informed him Master Tibeats had directed me

to call upon him for a keg of nails. Going

into the store-room, he rolled it out, at the same

time saying, if Tibeats preferred a different

size, he would endeavor to furnish them, but that I

might use those until further directed. Then

mounting his horse, which stood saddled and bridled

at the door, he rode away into the field, whither

the slaves had preceded him, while I took the keg on

my shoulder, and proceeding to the weaving-house,

broke in the head, and commenced nailing on the

clapboards.

[pg. 109]

As the day began to open, Tibeats came out of

the house to where I was, hard at work. He

seemed to be that morning even more morose and

disagreeable than usual. He was my master,

entitled by law to my flesh and blood, and to

exercise over me such tyrannical control as his mean

nature prompted; but there was no law that could

prevent my looking upon him with intense contempt.

I had just come round to the keg for a further

supply of nails, as he reached the weaving-house.

"I thought I told you to commence putting on

weather-boards this morning," he remarked.

"Yes, master, and I am about it," I replied.

"Where?" he demanded.

"On the other side," was my answer.

He walked round to the other side, examined my work for

a while, muttering to himself in a fault-finding

tone.

"Didn't I tell you last night to get a keg of nails of

Chapin?" he broke forth again.

"Yes, master, and so I did; and overseer said he would

get another size for you, if you wanted them, when

he came back from the field."

Tibeats walked to the keg, looked a moment at

the contents, then kicked it violently. Coming

towards me in a great passion, he exclaimed,

"G-d d__n you! I thought you knowed

something."

I made answer: "I tried to do as you told me,

[pg. 110]

master. I didn't mean anything wrong.

Overseer said -- " But he interrupted me with

such a flood of curses that I was unable to finish

the sentence. At length he ran towards the

house, and going to the piazza, took down one of the

overseer's whips. The whip had a short wooden

stock, braided over with leather, and was loaded at

the butt. The lash was three feet long, or

thereabouts, and made of raw-hide stands.

At first I was somewhat frightened, and my impulse was

to run. There was no one about except Rachel,

the cook, and Chapin's wife, and neither of

them were to be seen. The rest were in the

field. I knew he intended to whip me, and it

was the first time any one had attempted it since my

arrival at Avoyelles. I felt, moreover, that I

had been faithful - that I was guilty of no wrong

whatever, and deserved commendation rather than

punishment. My fear changed to anger, and

before he reached me I had made up my mind fully not

to be whipped, let the result be life or death.

Winding the lash around his hand, and taking hold of

the small end of the stock, he walked up to me, and

with a malignant look, ordered me to strip.

"Master Tibeats, said I, looking him boldly in

the face, "I will not." I was about to

say something further in justification, but with

concentrated vengeance, he sprang upon me, seizing

me by the throat with one hand, raising the whip

with the other, in the act of striking. Before

the blow descended, however,

[pg. 111]

I had caught him by the collar of the coat, and

drawn him closely to me. Reaching down, I

seized him by the ankle, and pushing him back with

the other hand, he fell over on the ground.

Putting one arm around his leg, and holding it to my

breast, so that his head and shoulders only touched

the ground, I placed my foot upon his neck. He

was completelly in my power. My blood was up.

It seemed to course through my veins like fire.

In the frenzy of my madness I snatched the whip from

his hand. He struggled with all his power;

swore that I should not live to see another day; and

that he would tear out my heart. But his

struggles and his treats were alike in vain. I

cannot tell how many times I struck him. Blow

after blow fell fast and heavy upon his wriggling

form. At length he screamed - cried murder -

and at last the blasphemous tyrant called on God for

mercy. But he who had never shown mercy did

not receive it. The stiff stock of the whip

warped round his cringing body until my right arm

ached.

Until this time I had been too busy to look about me.

Desisting for a moment, I saw Mrs. Chapin

looking from the window, and Rachel standing

in the kitchen door. Their attitudes expressed

the utmost excitement and alarm. His creams

had been heard in the field. Chapin was

coming as fast as he could ride. I stuck him a

blow or two more, then pushed him from me with such

a well-directed kick that he went rolling over on

the ground.

Rising to his feet, and brushing the dirt from his

[pg. 112]

hair, he stood looking at me, pale with rage.

We gazed at each other in silence. Not a word

was uttered until Chapin galloped up to us.

"What is the matter?" he cried out.

"Master Tibeats wants to whip me for using the

nails you gave me," I replied.

"What is the matter with the nails?" he inquired,

turning to Tibeats.

Tibeats answered to the effect that they were

too large, paying little heed, however, to Chapin's

question, but still keeping his snakish eyes

fastened maliciously on me.

"I am overseer here," Chapin began. "I

told Platt to take them and use them, and if

they were not of the proper size I would get others

on returning from the field. It is not his

fault. Besides, I shall furnish such nails as

I please. I hope you will understand that,

Mr. Tibeats."

Tibeats made no reply, but, grinding his teeth

and shaking his fist, swore he would have

satisfaction, and that it was not half over yet.

Thereupon he walked away, followed by the overseer,

and entered the house, the latter talking to him all

the while in a suppressed tone, and with earnest

gestures.

I remained where I was, doubting whether it was better

to fly or abide the result, whatever it might be.

Presently Tibeats came out of the house, and,

saddling his horse, the only property he possessed

besides myself, departed on the road to Chenyville."

when he was gone, Chapin came out, visibly exci-

[pg. 113]

ted, telling me not to stir, not to attempt to leae

the plantation on any account whatever. He

then went to the kitchen, and calling Rachel

out, conversed with her some time. Coming back

, he again charged me with great earnestness not to

run, saying my master was a rascal; that he had left

on no good errand, and that there might be trouble

before night. But at all events, he insisted

upon it, I must not stir.

At I stood there, feelings of unutterable agony

overwhelmed me. I was conscious that I had

subjected myself to unimaginable punishment.

The reaction that followed my extreme ebullition of

anger produced the most painful sensations of

regret. An unfriended, helpless slave - what

could I do, what could I say, to

justify, in the remotest manner, the heinous act I

had committed, of resenting a white man's

contumely and abuse. I tried to pray - I tried

to beseech my Heavenly Father to sustain me in my

sore extremity, but emotion choked my utterance, and

I could only bow my head upon my hands and weep.

For at least an hour I remained in this situation,

finding relief only in tears, when, looking up, I

beheld Tibeats, accompanied by two horsemen,

coming down the bayou. They rode into the

yard, jumped from their horses, and approached me

with large whips, one of them also carrying a coil

or rope.

"Cross your hands," commanded Tibeats, with the

addition of such a shuddering expression of

blasphemy as is not decorous to repeat.

[pg. 114]

"You need not bind me, Master Tibeats, I am

ready to go with you anywhere," said I.

One of his companions then stepped forward, swearing if

I made the least resistance he would break my head -

he would tear me limb from limb - he would cut my

black throat - and giving wide scope to other

similar expressions. Perceiving any

importunity altogether vain, I crossed my hands,

submitting humbly to whatever disposition they might

please to make of me. Thereupon Tibeats

tied my wrists, drawing the rope around them with

his utmost strength. Then he bound my ankles

in the same manner. In the meantime the other

two had slipped a cord within my elbows, running it

across my back, and tying it firmly. It was

utterly impossible to move hand or foot. With

a remaining piece of rope Tibeats made an

awkward noose, and placed it about my neck.

"Now, then," inquired one of Tibeats'

companions, "where shall we hang the nigger?"

One proposed such a limb, extending from the body of a

peach tree, near the spot where we were standing.

He comrade objected to it, alleging it would break,

and proposed another. Finally they fixed upon

the latter.

During this conversation, and all the time they were

binding me, I uttered not a word. Overseer

Chapin, during the progress of the scene, was

walking hastily back and forth on the piazza.

Rachel was crying by the kitchen door, and

Mrs. Chapin was still

[pg. 115]

looking from the window. Hope died within my

heart. Surely my time had come. I should

never behold the light of another day - never behold

the faces of my children - the sweet anticipation I

had cherished with such fondness. I should

that hour struggle through the fearful agonies of

death! None would mourn for me - none revenge

me. Soon my form would be mouldering in that

distant soil, or, perhaps, be cast to the slimy

reptiles that filled the stagnant waters of the

bayou! Tears flowed down my cheeks, but they

only afforded a subject of insulting comment for my

executioners.

At length, as they were dragging me towards the tree,

Chapin, who had momentarily disappeared from

the piazza, came out of the house and walked towards

us. He had a pistol in each hand, and as near

as I can now recall to mind, spoke in a firm,

determined manner, as follows:

"Gentlemen, I have a few words to say. You had

better listen to them. Whoever moves that

slave another foot from where he stands is a dead

man. In the first place, he does not deserve

this treatment. It is a shame to murder him in

this manner. I never knew a more faithful boy

than Platt. You, Tibeats, are in

the fault yourself. You are pretty much of a

scoundrel, and I know it, and you richly deserve the

flogging you have received. In the next place,

I have been overseer on this plantation seven years,

and, in the absence of William Ford, am

master here. My duty is to protect his

interests, and that duty I shall

[pg. 116]

perform. You are not responsible - you are a

worthless fellow. Ford holds a mortgage

on Platt of four hundred dollars.

If you hang him he loses his debt. Until that

is canceled you have no right to take his life.

You have no right to take it any way. There is

a law for the slave as well as for the white man.

You are no better than a murderer.

"As for you," addressing Cook and Ramsay,

a couple of overseers from neighboring plantations,

"as for you - begone! If you have any regard

for your own safety, I say, begone."

Cook and Ramsay, without a further word,

mounted their horses and rode away. Tibeats,

in a few minutes, evidently in fear, and overawed by

the decided tone of Chapin, sneaked off like

a coward, as he was, and mounting his horse,

followed his companions.

I remained standing where I was, still bound, with the

rope around my neck. As soon as they were

gone, Chapin called Rachel, ordering

her to run to the field, and tell Lawson to

hurry to the house without delay, and bring the

brown mule with him, an animal much prized for its

unusual fleetness. Presently the boy appeared.

"Lawson," said Chapin, "you must go to

the Pine Woods. Tell your master Ford

to come here at once - that he must not delay a

single moment. Tell him they are trying to

murder Platt. Now hurry, boy. Be

at the Pine Woods by noon if you kill the mule."

Chapin stepped into the house and wrote a pass.

When he returned, Lawson was at the door,

mounted

[pg. 117]

on his mule. Receiving the pass, he plied the

whip right smartly to the beast, dashed out of the

yard, and turning up the bayou on a hard gallop, in

less time than it ahs taken me to describe the

scene, was out of sight.

<

BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS >