|

STILL'S

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORDS,

REVISED EDITION.

(Previously Published in 1879 with title: The Underground Railroad)

WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR.

NARRATING

THE HARDSHIPS, HAIRBREADTH ESCAPES AND DEATH STRUGGLES

OF THE

SLAVES

IN THEIR EFFORTS FOR FREEDOM.

TOGETHER WITH

SKETCHES OF SOME OF THE EMINENT FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, AND

MOST LIBERAL AIDERS AND ADVISERS OF THE ROAD

BY

WILLIAM STILL,

For many years connected with the Anti-Slavery Office in

Philadelphia, and Chairman of the Acting

Vigilant Committee of the Philadelphia Branch of the Underground

Rail Road.

Illustrated with 70 Fine Engravings

by Bensell, Schell and Others,

and Portraits from Photographs from Life.

Thou shalt not deliver unto his

master the servant that has escaped from his master unto thee. -

Deut. xxiii 16.

SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION.

PHILADELPHIA:

WILLIAM STILL, PUBLISHER

244 SOUTH TWELFTH STREET.

1886

pp. 493 - 528

[Page 493] - continued

_______________

ARRIVAL FROM

RICHMOND, 1859

CORNELIUS HENRY JOHNSON. FACE CANADA-WARD

FOR YEARS.

Quite an

agreeable interview took place between Cornelius

and the Committee. He gave his experience of

Slavery pretty fully, and the Committee enlightened him

as to the workings of the Underground Rail Road, the

value of freedom, and the safety of Canada as a refuge.

Cornelius was a single man, thirty-six years of

age, full black, medium size, and intelligent. He

stated that he had had his face set toward Canada

[Page 494]

for a long while. Three times he had made an

effort to get out of the prison house. “Within the

last four or five years, times have gone pretty hard

with me. My mistress, Mrs. Mary F. Price,

had lately put me in charge of her brother, Samuel M.

Bailey, a tobacco merchant of Richmond. Both

believed in nothing as they did in Slavery; they would

sooner see a black man dead than free. They were

about second class in society. He and his sister

own well on to one hundred head, though within the last

few years he has been thinning off the number by sale.

I was allowed one dollar a week for my board; one dollar

is the usual allowance for slaves in my situation.

On Christmas week he allowed me no board money, but made

me a present of seventy-five cents; my mistress added

twenty-five cents, which was the extent of their

liberality. I was well cared for. When the

slaves got sick he doctored them himself, he was too

stingy to employ a physician. If they did not get

well as soon as he thought they should, he would order

them to their work, and if they did not go he would beat

them. My cousin was badly beat last year in the

presence of his wife, and he was right sick. Mr.

Bailey was a member of St. James’ church, on

Fifth street, and my mistress was a communicant of the

First Baptist church on Broad Street. She let on

to be very good.”

“I am one of a family of sixteen; my mother and eleven

sisters and brothers are now living; some have been sold

to Alabama, and some to Tennessee, the rest are held in

Richmond. My mother is now old, but is still in

the service of Bailey. He promised to take

care of her in her old age, and not compel her to labor,

so she is only required to cook and wash for a dozen

slaves. This they consider a great favor to the

old ‘grand mother.’ It was only a year ago he

cursed her and threatened her with a flogging. I

left for nothing else but because I was dissatisfied

with Slavery. The threats of my master

caused me to reflect on the North and South. I had

an idea that I was not to die in Slavery. I

believed that God would assist me if I would try.

I then made up my mind to put my case in the hands of

God, and start for the Underground Rail Road. I

bade good-bye to the old tobacco factory on Seventh

street, and the First African Baptist church on Broad

street (where he belonged), where I had so often heard

the minister preach ‘servants obey your masters;’ also

to the slave pens, chain gangs, and a cruel master and

mistress, all of which I hoped to leave forever.

But to bid good-bye to my old mother in chains, was no

easy job, and if my desire for freedom had not been as

strong as my desire for life itself, I could never have

stood it; but I felt that I could do her no good; could

not help her if I staid. As I was often threatened

by my master, with the auction-block, I felt I must give

up all and escape for my life.”

Such was substantially the story of Cornelius

Henry Johnson. He talked for an hour as

one inspired, and as none but fugitive slaves could

talk.

[Page 495]

--------------------

ARRIVAL FROM DELAWARE, 1858.

THEOPHILUS COLLINS, ANDREW

JACKSON BOYCE, HANDY BURTON AND ROBERT JACKSON.

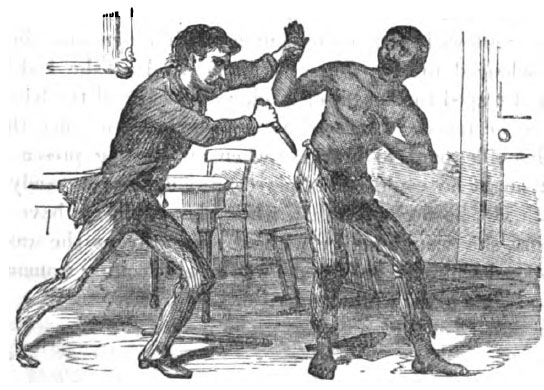

A DESPERATE, BLOODY

STRUGGLE - GUN, KNIFE AND FIRE SHOVEL, USED BY

AN INFURIATED MASTER.

Judged from their outward appearance, as well as

from the fact that they were from the

neighboring State of Delaware, no extraordinary

revelations were looked for from the above-named

party. It was found, however, that one of

their numbers, at least, had a sad tale of

outrage and cruelty to relate. The facts

stated are as follows:

THEOPHILUS is twenty-four years of age,

dark, height and stature hardly medium, with

faculties only about average compared with

ordinary fugitives from Delaware and Maryland.

His appearance is in no way remarkable.

His bearing is subdued and modest; yet he is not

lacking in earnestness. Says Theophilus,

"I was in servitude under a man named

Houston, near Lewes, Delaware; he was a very

mean man, he didn't allow you enough to eat, nor

enough clothes to wear. He never allowed

to drop of tea, or coffee, or sugar, and if you

didn't eat your breakfast before day he wouldn't

allow you any, but would drive you out without

any. He had a wife; she was mean, too,

meaner than he was. Four years ago last

Fall my master cut my entrails* out for going to

meeting at Daniel Wesley's church one

Sabbath night. Before day, Monday morning,

he called me up to whip me; called me into his

dining-room, locked the doors, and then ordered

me to pull off my shirt. I told him no,

sir, I wouldn't; right away he went and got the

cowhide, and gave me about twenty over my head

with the butt. He tore my shirt off, after

I would not pull it off; he

ordered me to cross my hands.

I didn't do that. After I wouldn't do

that,

-------------------------

*Entrails: Internal organs

[Page 496]

he went and got his gun and

broke the breech of that over my head. He

then seized up the fire-tongs and struck me over

the head ever so often. The next thing he

took was the parlor shovel and he beat on me

with that till he broke the handle; then he took

the blade and stove it at my head with all his

might. I told him that I was bound to come

out of that room. He run up to the door

and drawed his knife and told me if I ventured

to the door he would stab me. I never made

it any better or worse, but aimed straight for

the door; but before I reached it he stabbed me,

drawing the knife (a common picket knife) as

hard as he could rip across my stomach; right

away he began stabbing me about my head," (marks

were plainly to be seen). After a

desperate struggle, Theophilus succeeded

in getting out of the building.

"I started," said he, "at once for Georgetown, carrying

a part of my entrails in my hands for the whole

journey, sixteen miles. I went to my young

masters, and they took me to an old colored

woman, called Judah Smith, and for five

days and nights I was under treatment of Dr.

Henry Moore, Dr. Charles Henry Richards,

and Dr. William Newall all these attended

me. I was not expected to live for a long

time, but the Doctors cured me at last."

ANDREW

reported that he fled from Dr.

David Houston. "I left because of my

master's meanness to me; he was a very mean man

to his servants," said Andrew, "and

I got so tired of him I couldn't stand him any

longer." Andrew was about

twenty-six years of age, ordinary size; color,

brown, and was entitled to his freedom, but knew

not how to secure it by law, so resorted to

Underground Rail Road method.

HANDY,

another of this party, said that he left because

the man who claimed to be his master "was so

hard." The man by whom he had been wronged

was known where he came from by the name of

Shepherd Burton, and was in the farming

business. "He was a churchman," said

Handy, "but never allowed me to go to church

a half dozen times in my life."

ROBERT

belonged to Mrs. Mary Hickman, at least

she had him in her possession and reaped the

benefit of his hire and enjoyed the leasure and

ease thereof while he toiled. For some

time prior to his leaving, this had been a thorn

in his side, hard to bear; so when an opening

presented itself by which he thought he could

better his condition, he was ready to try the

experiment. He, however, felt that while

she would not have him to look to for support,

she would not be without sympathy, as she was a

member of the Episcopal Church; besides she was

an old-looking woman and might not need his help

a great while longer.

[Page 497]

ARRIVAL FROM

RICHMOND, 1859.

STEPNEY BROWN.

Stepney was an extraordinary man, his

countenance indicating great goodness of heart, and his

gratitude to his heavenly Father for his deliverance

proved that he was fully aware of the Source whence his

help had come. Being a man of excellent natural

gifts, as well as of religious fervor and devotion to a

remarkable degree, he seemed admirably fitted to

represent the slave in chains, looking up to God with an

eye of faith, and again the fugitive in Canada

triumphant and rejoicing with joy unspeakable over his

deliverance, yet not forgetting those in bonds, as bound

with them. The beauty of an unshaken faith

in the good Father above could scarcely have shone with

a brighter lustre than was seen in this simple-hearted

believer.

STEPNEY was thirty-four years of age, tall,

slender, and of a dark hue. He readily confessed

that he fled from Mrs. Julia A. Mitchell, of

Richmond; and testified that she was decidedly stingy

and unkind, although a member of St. Paul’s church.

Still he was wholly free from acrimony, and even in

recounting his sufferings was filled with charity

towards his oppressors. He said, “I was moved to

leave because I believed that I had a right to be a free

man.”

He was a member of the Second Baptist church, and

entertained strong faith that certain infirmities, which

had followed him through life up to within seven years

of the time of his escape, had all been removed through

the Spirit of the Lord. He had been an eye-witness

to many outrages inflicted on his fellow-men. But

he spoke more of the sufferings of others than his own.

His stay was brief, but interesting. After his

arrival in Canada he turned his attention to industrial

pursuits, and cherished his loved idea that the Lord was

very good to him. Occasionally he would write to

express his gratitude to God and man, and to inquire

about friends in different localities, especially those

in bonds.

The following letters are specimens, and speak for

themselves:

| |

|

CLIFTON HOUSE, NIAGARA FALLS,

August the 27. |

DEAR

BROTHER:—-It is with

pleasure i take my pen in hand to write a few lines to

in form you that i am well hopeping these few lines may

fine you the same i am longing to hear from you and your

family i wish you would say to Julis Anderson

that he must realy excuse me for not writing but i am in

hopes that- he is doing well. i have not heard no

news from Virgina. plese to send me all the news

say to Mrs. Hunt an you also forever pray

for me knowing that God is so good to us. i have

not seen brother John Dungy for 5 months,

but we have corresponded together but he is doing well

in Brandford. i am now at the falls an have been

on here some time an i shall with the help of the lord

locate myself somewhere this winter an go to school

excuse me for not annser your letter sooner

[Page 498]

knowing that i cannot write well you please to send me

one of the earliest papers send me word if any of our

friends have been passing through i know that you are

very busy but ask your little daughter if she will

annser this letter for you i often feel that i cannot

turn god thanks enough for his blessings that he has

bestoueth upon me. Say to brother suel that he

must not forget what god has consighn to his hand, to do

that he must pray in his closet that god might teach

him. say to mr. Anderson that i hope he

have retrad an has seeked the lord an found him precious

to his own soul for he must do it in this world for he

cannot do it in the world to come. i often think about

the morning that i left your house it was such a sad

feeling but still i have a hope in crist do you think it

is safe in boston my love to all i remain your brother,

| |

|

BRANTFORD,

March 3d, 1860. |

MR. WILLIAM

STILL, DEAR

SIR:—I now

take the pleasure of writing to you a few lines write

soon hoping to find you enjoying perfect health, as I am

the same.

My joy within is so great that I cannot find words to

express it. When I met with my friend brother

Dungy who stopped at your house on his way to Canada

after having a long chase after me from Toronto to

Hamilton he at last found me in the town of Brant ford

Canada West and ought we not to return Almighty God

thanks for delivering us from the many dangers and

trials that beset our path in this wicked world we live

in.

I have long been wanting to write to you but I entirely

forgot the number of your house Mr. Dungy

luckily happened to have your directions with him.

Religion is good when we live right may God help you to

pray often to him that he might receive you at the hour

of your final departure. Yours most respectfully.

| |

STEPNEY

BROWN, per

Jas.

A. Walkinshaw. |

DEAR

SIR:—I take the pleasure of

dropping you a few lines, I am yet residing in Brantford

and I have been to work all this summer at the falls and

I have got along remarkably well, surely God is good to

those that put their trust in him I suppose you have

been wondering what has become of me but I am in the

lands of living and long to hear from you and your

family. I would have wrote sooner, but the times

has been such in the states I have not but little news

to send you and I’m going to school again this winter

and will you be pleased to send me word what has become

of Julius Anderson and the rest-of my

friends and tell him I would write to him if I knew

where to direct the letter, please send me word whether

any body has been along lately that knows me. I

know that you are busy but you must take time and answer

this letter as I am anxious to hear from you, but

nevertheless we must not forget our maker, so we cannot

pray too much to our lord so I hope that mr.

Anderson has found peace with God for me myself

really appreciate that hope that I have in Christ, for I

often find myself in my slumber with you and I hope we

will meet some day. Mr. Dungy sends

his love to you I suppose you are aware that he is

married, he is luckier than I am or I must get a little

foothold before I do marry if I ever do. I am in a very

comfortable room all fixed for the winter and we have

had one snow. May the lord be with you and all you

and all your house hold. I remain forever your

brother in Christ,

[Page 499]

ARRIVAL FROM

MARYLAND, 1859.

JIM KELL, CHARLES HEATH,

WILLIAM CARLISLE, CHARLES RINGGOLD, THOMAS

MAXWELL, AND SAMUEL SMITH.

On the evening of the Fourth of July, while all was

hilarity and rejoicing the above named very interesting

fugitives arrived from the troubled district, the

Eastern shore of Maryland, where so many conventions had

been held the previous year to prevent escapes; where

the Rev. Samuel Green had been

convicted and sent to the penitentiary for ten years for

having a copy of Uncle Tom's Cabin in his humble home;

where so many parties, on escaping, had the good sense

and courage to secure their flight by bringing their

masters' horses and carriages a good way on their

perilous journey.

SAM had been tied up and beat

many times severely. WILLIAM

had been stripped naked, and

frequently and cruelly cowhided. Thomas had

been clubbed over his head more times than a few.

Jim had been whipped with clubs and switches

times without number. Charles had had five

men on him at one time, with cowhides, his master in the

lead.

CHARLES HEATH had had his head

cut shockingly, with a club, in the hands of his master;

this well cared-for individual in referring to his kind

master, said: “I can give his character right along, he

was a perfect devil. The night we left, he had a

woman tied up - God knows what he done. He was

always blustering, you could never do enough for him no

how. First thing in the morning and last thing at

night, you would hear him cussing — he would cuss in

bed. He was a large farmer, all the time drunk.

He had a good deal of money but not much character.

He was a savage, bluff, red face-looking concern."

Thus, in the most earnest, as well as in an intelligent

manner, Charles described the man (Aquila

Cain ), who had hitherto held him under the yoke.

JAMES left his mother, Nancy

Kell, two brothers, Robert and Henry,

and two sisters, Mary and Annie; all

living in the neighborhood whence he fled. Besides

these, he had eight brothers and sisters living in

Baltimore and elsewhere, under the yoke. He was

twenty-four years of age, of a jet color, but of a manly

turn. He fled from Thomas Murphy, a

farmer, and regular slave-holder. Charles

Heath was twenty-five years of age, medium size,

full black, a very keen-looking individual.

WILLIAM was also of unmixed

blood, shrewd and wide-awake for his years, - had been

ground down under the heel of Aquila Cain.

He left his mother and two sisters.

CHARLES RINGGOLD was eighteen

years of age; no white blood showed itself in the least

in this individual. He fled from Dr. Jacob

Preston, a member of the Episcopal Church, and a

practical farmer with twenty head of slaves. “He

was not so bad, but his wife was said to be a 'stinger.'

” Charles left his mother and father

behind, also four sisters.

[Page 500]

THOMAS was of pure blood, with a

very cheerful, healthy-looking countenance, -

twenty-one years of age, and was to "come free"

at twenty-five, but he had too much good sense

to rely upon the promises of slave-holders in

matters of this kind. He too belonged to

Cain who, he said, was constantly talking

about selling, etc. He left his father and

mother.

After being furnished with food, clothing, and free

tickets, they were forwarded on in triumph and

full of hope.

------------------------

SUNDRY

ARRIVALS, 1859

JOHN EDWARD LEE, JOHN

HILLIS, CHARLES ROSS, JAMES RYAN, WILLIAM

JOHNSTON, EDWARD WOOD, CORNELIUS FULLER AND HIS

WIFE HARRIET, JOHN PINKET, ANSAL CANNON, AND

JAMES BROWN.

JOHN came from Maryland,

and brought with him a good degree of pluck. He

satisfied the Committee that he fully believed

in freedom , and had proved his faith by his

works, as he came in contact with pursuers, whom

he put to flight by the use of an ugly-looking

knife, which he plunged into one of them,

producing quite a panic; the result was that he

was left to pursue his Underground Rail Road

journey without further molestation. There

was nothing in John's appearance which would

lead one to suppose that he was a blood-thirsty

or bad man, although a man of uncommon muscular

powers; six feet high, and quite black, with

resolution stamped on his countenance. But

when he explained how he was enslaved by a man

named John B. Slade, of Harford Co., and

how, in some way or other, he became entitled to

his freedom, and just as the time arrived for

the consummation of his long prayed - for boon,

said Slade was about to sell him, -after

this provocation, it was clear enough to

perceive how John came to use his knife.

JOHN HILLIS is was a tiller of

the ground under a widow lady (Mrs. Louisa Le

Count), of the New Market District,

Maryland. He signified to the mistress,

that he loved to follow the water, and that he

would be just as safe on water as on land, and

that he was discontented. The widow heard

John's plausible story, and saw nothing

amiss in it, so she consented that he should

work on a schooner. The name of the craft

was “Majestic.” The hopeful John

endeavored to do his utmost to please, and was

doubly happy when he learned that the “Majestic”

was to make a trip to Philadelphia. On

arriving John's eyes were opened to see

that he owed Mrs. Le Count nothing, but

that she was largely indebted to him for years

of unrequited toil; he could not, therefore,

consent to go back to her. He was troubled

to think of his poor wife and children, whom he

had left in the hands of Mrs. Harriet

Dean, three quarters of a mile from New

Market; but it was easier for him to

[Page 501]

imagine plans by which he could get them off than to

incur the hazard of going back to Maryland; therefore he

remained in freedom.

CHARLES Ross was clearly of the

opinion that he was free-born, but that he had been

illegally held in Slavery, as were all his brothers and

sisters, by a man named Rodgers, a farmer, living

near Greensborough, in Caroline county, Md. Very

good reasons were given by Charles for the charge

which he made against Rodgers, and it went far

towards establishing the fact, that “colored men had no

rights which white men were bound to respect," in

Maryland. Although he was only twenty-three years

of age, he had fully weighed the matter of his freedom,

and appeared firmly set against Slavery.

WILLIAM JOHNSON was owned by a

man named John Bosley, a farmer, living

near Gun Powder Neck, Maryland. One morning he,

unexpectedly to William, gave him a terrible

cowhiding, which, contrary to the master's designs, made

him a firm believer, in the doctrine of immediate

abolition, and he thought, that from that hour he must

do something against the system if nothing more than to

go to Canada. This determination was so strong,

that in a few weeks afterwards he found himself on the

Underground Rail Road. He left one brother and one

sister; his mother was dead, and of his father's

whereabouts he knew nothing. William was

nineteen years of age, brown color, smart and

good-looking.

EDWARD WOOD was a “chattel" from

Drummerstown, Accomac county, Virginia, where he had

been owned by a farmer, calling himself James

White; a man who “drank hard and was very crabbed,”

and before Edward left owned eleven head of

slaves. Edward left a wife and three

children, but the strong desire to be free, which had

been a ruling passion of his being from early boyhood,

rendered it impossible for him to stay, although the

ties were very hard to break. Slavery was crushing

him hourly, and he felt that he could not submit any

longer.

CORNELIUS FULLER, and his wife,

HARRIET, escaped together from

Kent county, Maryland. They belonged to separate

masters; Cornelius, it was said, belonged to the

Diden Estate; his wife to Judge

Chambers, whose Honor lived in Chestertown. He

is no man for freedom, bless you,” said Harriet.

“He owned more slaves than any other man in that part of

the country; he sells sometimes, and he hired out a

great many; would hire them to any kind of a master, if

he half killed you.” Cornelius and

Harriet were obliged to leave their daughter

Kitty, who was thirteen years of age.

JOHN PINKET and Ansal

Cannon took the Underground Rail Road cars at New

Market, Dorchester county, Maryland. John

was a tall young man, of twenty-seven years of age, of

an active turn of mind and of a fine black color.

He was the property of Mary Brown, a

widow, firmly grounded in the love of Slavery; believing

[Page 502]

that a slave had no business to get tired or desire his

freedom. She sold one of John's sisters to

Georgia, and before John fled, had still in her

possession nine head of slaves. She was a member

of the Methodist church at East New Market. From

certain movements which looked very suspicious in

John's eyes, he had been allotted to the Southern

Market, he there fore resolved to look out for a

habitation in Canada. He had a first-rate

corn-field education, but no book learning. Up to

the time of his escape, John had shunned

entangling himself with a wife.

ANSAL was twenty-five years of

age, well-colored, and seemed like a good natured and

well-behaved article. He escaped from Kitty

Cannon, another widow, who owned nine chattels.

“Sometimes she treated her slaves pretty well,” was the

testimony of Ansal. He ran away because he

did not get pay for his services. In thus being

deprived of his hire, he concluded that he had no

business to stay if he could get away.

-------------------------

ARRIVAL FROM

MARYLAND, 1859

JAMES BROWN.

A more giant-like looking passenger than the

above named individual had rarely ever passed

over the road. He was six feet three

inches high, and in every respect, a man of

bone, sinew and muscle. For one who had

enjoyed only a field hand's privileges for

improvement, he was not to be despised.

JIM owed service to Henry Jones; at least he

admitted that said Jones claimed him, and

had hired him out to himself for seven dollars

per month. While this amount seemed light,

it was much heavier than Jim felt willing

to meet solely for his master's benefit.

After giving some heed to the voice of freedom

within, he considered that it behooved him to

try and make his way to some place where men

were not guilty of wronging their neighbors out

of their just hire. Having heard of the

Underground Rail Road running to Canada, he

concluded to take a trip and see the country,

for himself; so he arranged his affairs with

this end in view, and left Henry Jones

with one less to work for him for nothing.

The place that he fled from was called North

Point, Baltimore county. The number of

fellow slaves left in the hands of his old

master, was fifteen .

-------------------------

ARRIVAL FROM

DELAWARE, 1859.

EDWARD, JOHN, AND CHARLES

HALL.

The above named individuals were brothers from

Delaware. They were young; the eldest

being about twenty, the youngest not far from

seventeen years of age. [Page 503]

EDWARD was

serving on a farm, under a man named Booth. Perceiving

that Booth was “running through his property” very fast by

hard drinking, Edward's better judgment admonished him that his

so-called master would one day have need of more rum money, and that

he might not be too good to offer him in the market for what he

would bring. Charles resolved that when his brothers

crossed the line dividing Delaware and Pennsylvania, he would not be

far behind.

The mother of these boys was freed at the age of

twenty-eight, and lived in Wilmington, Delaware. It was owing

to the fact that their mother had been freed that they entertained

the vague notion that they too might be freed; but it was a well

established fact that thousands lived and died in such a hope

without ever realizing their expectations. The boys, more

shrewd and wide awake than many others, did not hearken to such

"stuff.” The two younger heard the views of the elder brother,

and expressed a willingness to follow him. Edward,

becoming satisfied that what they meant to do must be done quickly,

took the lead, and off they started for a free State.

JOHN was owned by one James B. Rodgers, a

farmer, and “a most every kind of man,” as John expressed

himself; in fact John thought that his owner was such a

strange, wicked, and cross character that he couldn't tell himself

what he was. Seeing that slaves were treated no better than

dogs and hogs, John thought that he was none too young to be

taking steps to get away.

CHARLES was held by James Rodgers, Sr., under

whom he said that he had served nine years with faint prospects of

some time becoming free, but when, was doubtful.

-------------------------

ARRIVAL FROM

VIRGINIA, 1859.

JAMES TAYLOR, ALBERT GROSS,

AND JOHN GRINAGE.

To see mere lads, not

twenty one years of age, smart enough to outwit

the very shrewdest and wisest slave-holders of

Virginia was very gratifying. The young

men composing this arrival were of this

keen-sighted order.

JAMES was only a little turned of

twenty, of a yellow complexion , and

intelligent. A trader, by the name of

George Ailer, professed to own

James. He said that he had been used

tolerable well, not so bad as many had been

used. James was learning the

carpenter trade; but he was anxious to obtain

his freedom, and finding his two companions true

on the main question, in conjunction with them

he contrived a plan of escape, and took out.

'His father and mother, Harrison and

Jane Taylor, were left at

Fredericksburg to mourn the absence of their

son.

ALBERT was in his twentieth year,

the picture of good health, not

[Page 504]

homely by any

means, although not of a fashionable color.

He was under the patriarchal protection of a man

by the name of William Price, who carried

on farming in Cecil county, Maryland.

Albert testified that he was a bad man.

JOHN GRINAGE, was only twenty, a

sprightly, active young man, of a brown color.

He came from Middle Neck, Cecil county, where he

had served under William Flintham, a

farmer.

-------------------------

SUNDRY

ARRIVALS FROM MARYLAND (1859)

AND OTHER PLACES.

JAMES ANDY WILKINS, and

wife

LUCINDA, with their little boy,

CHARLES, CHARLES HENRY GROSS, A WOMAN with her

TWO CHILDREN - one in her arms - JOHN BROWN,

JOHN ROACH, and wife LAMBRY, and HENRY

SMALLWOOD.

The above-named passengers did not all come from the

same place, or exactly at the same time; but for the

sake of convenience they are thus embraced under a

general head.

JAMES ANDY WILKINS “gave the

slip” to a farmer, by the name of George

Biddle, who lived one mile from Cecil, Cecil county,

Maryland. While he hated Slavery, he took a

favorable view of his master in some respects at least,

as he said that he was a “moderate man in talk; but “sly

in action.” His master provided him with two pairs

of pantaloons in the summer, and one in the winter, also

a winter jacket, no vest, no cap, or hat. James

thought the sum total for the entire year's clothing

would not amount to more than ten dollars. Sunday

clothing he was compelled to procure for himself by

working of nights; he made axe handles, mats, etc., of

evenings, and caught musk rats on Sunday, and availed

him self of their hides to procure means for his most

pressing wants. Besides these liberal privileges

his master was in the habit of allowing him two whole

days every harvest, and at Christmas from twenty-five

cents to as high as three dollars and fifty cents, were

lavished upon him.

His master was a bachelor, a man of considerable means,

and “kept tolerable good company," and only owned two

other slaves, Rachel Ann Dumbson

and John Price.

LUCINDA, the companion of

James, was twenty-one years of age, good looking,

well-formed and of a brown color. She spoke of a

man named George Ford as her owner.

He, however, was said to be of the “mode rate class” of

slave-holders; Lucinda being the only slave

property he possessed, and she came to him through his

wife (who was a Methodist ). The master was an

outsider, so far as the Church was concerned. Once

[Page 505]

in a great while Lucinda was allowed to go to

church, when she could be spared from her daily routine

of cooking, washing, etc. Twice a week she was

permitted the special favor of seeing her husband.

These simple privations not being of a grave character,

no serious fault was found with them; yet Lucinda

was not without a strong ground of complaint. Not

long before escaping, she had been threatened with the

auction-block; this fate she felt bound to avert, if

possible, and the way she aimed to do it was by escaping

on the Underground Rail Road. Charley, a bright

little fellow only three years of age, was "contented

and happy” enough. Lucinda left her father,

Moses Edgar Wright, and two

brothers, both slaves. One belonged to “Francis

Crookshanks,” and the other to Capt.

Jim Mitchell. Her mother, who was known

by the name of Betsy Wright, escaped when

she (Lucinda) was seven years of age. Of

her whereabouts nothing further had ever been heard.

Lucinda entertained strong hopes that she might

find her in Canada.

CHARLES HENRY Gross began life in

Maryland, and was made to bear the heat and burden of

the day in Baltimore, under Henry Slaughter,

proprietor of the Ariel Steamer. Owing to hard

treatment, Charles was induced to fly to Canada

for refuge.

A woman with two children, one in her arms, and the

other two years of age (names, etc., not recorded), came

from the District of Columbia. Mother and

children, appealed loudly for sympathy.

JOHN BROWN, being at the beck of

a man filling the situation of a common clerk (in the

shoe store of McGrunders), became dissatisfied.

Asking himself what right Benjamin Thorn

(his professed master) had to his hire, he was led to

see the injustice of his master, and made up his mind,

that he would leave by the first train, if he could get

a genuine ticket via the Underground Rail Road. He

found an agent and soon had matters all fixed. He

left his father, mother and seven sisters and one

brother, all slaves. John was a man small

of stature, dark, with homely features, but he was very

determined to get away from oppression.

JOHN and LAMBY ROACH had been

eating bitter bread under bondage near Seaford.

John was the so-called property of Joshua

O'Bear, "a fractious, hard-swearing man, and when

mad would hit one of his slaves with anything he could

get in his hands." John and his companion

made the long journey on foot. The former had been

trained to farm labor and the common drudgery of slave

life. Being a man of thirty-three years of age,

with more than ordinary abilities, he had given the

matter of his bondage considerable thought, and seeing

that his master “got worse the older he got,” together

with the fact, that his wife had recently been sold, he

was strongly stirred to make an effort for Canada.

While it was a fact, that his wife had already been

sold, as above stated, the change of ownership was not

to take place for some months, consequently John “ took

out in a hurry.”

[Page 506]

His wife was the property of Dr. Shipley,

of Seaford, who had occasion to raise some money for

which he gave security in the shape of this wife and

mother. Horsey was the name of the

gentleman from whom it was said that he obtained the

favor; so when the time was up for the payment to be

made, the Dr. was not prepared. Horsey,

therefore, claimed the collateral (the wife) and thus

she had to meet the issue, or make a timely escape to

Canada with her husband. No way but walking was

open to them. Deciding to come this way, they

prosecuted their journey with uncommon perseverance and

success. Both were comforted by strong faith in

God, and believed that He would enable them to hold out

on the road until they should reach friends.

HENRY SMALLWOOD saw that he was

working every day for nothing, and thought that he would

do better. He described his master (Washington

Bonafont) as a sort of a rowdy, who drank pretty

hard, leaving a very unfavorable impression on

Henry's mind, as he felt almost sure such conduct

would lead to a sale at no distant day. So he was

cautious enough to “take the hint in time.”

Henry left in company with nine others; but after

being two days on the journey they were routed and

separated by their pursuers. At this point

Henry lost all trace of the rest. He heard

afterwards that two of them had been captured, but

received no further tidings of the others.

Henry was a fine representative for Canada; a tall,

dark, and manly-looking individual, thirty-six years of

age. He left his father and mother behind.

ARRIVAL FROM RICHMOND, 1859.

HENRY JONES AND TURNER

FOSTER.

HENRY was

left free by the will of his mistress (Elizabeth

Mann), but the heirs were making desperate efforts

to overturn this instrument. Of this, there was so

much danger with a Richmond court, that Henry

feared that the chances were against him; that the court

was not honest enough to do him justice. Being a

man of marked native foresight, he concluded that the

less he talked about freedom and the more he acted the

sooner he would be out of his difficulties. He was

called upon, however, to settle certain minor matters,

before he could see his way clear to move in the

direction of Canada; for instance, he had a wife on his

mind to dispose of in some way, but how he could not

tell. Again, he was not in the secret of the

Underground Rail Road movement; he knew that many got

off, but how they managed it he was ignorant. If

he could settle these two points satisfactorily, he

thought that he would be willing to endure any sacrifice

for the sake of his freedom. He found an agent of

the Under ground Rail Road, and after surmounting

various difficulties, this point was

[Page 507]

settled. As good luck would have it, his wife, who was a free

woman, although she heard the secret with great sorrow, had the good

sense to regard his step for the best, and thus he was free to

contend with all other dangers on the way.

He encountered the usual suffering, and on his arrival

experienced the wonted pleasure. He was a man of forty-one

years of age, spare made, with straight hair, and Indian complexion,

with the Indian's aversion to Slavery.

TURNER, who was a fellow-passenger with Henry,

arrived also from Richmond. He was about twenty-one, a bright,

smart, prepossessing young man. He fled from A. A. Mosen,

a lawyer, represented to be one of the first in the city, and a firm

believer in Slavery. Turner differed widely with his

master with reference to this question, although, for prudential

reasons, he chose not to give his opinion to said Mosen.

-------------------------

ARRIVAL FROM

MARYLAND.

TWO YOUNG MOTHERS, EACH

WITH BABES IN THEIR ARMS - ANNA ELIZABETH YOUNG

AND SARAH JANE BELL - WHIPPED TILL THE BLOOD

FLOWED.

The appearance of these young mothers a first

produced a sudden degree of pleasure, but their

story of suffering quite as suddenly caused the

most painful reflections. It was hardly

possible to listen to their tales of outrage and

wrong with composure. Both came from Kent

county, Maryland, and reported that they fled

from a man by the name of Massey; a man

of low stature, light-complexioned, with dark

hair, dark eyes, and very quick temper; given to

hard swearing as a common practice; also, that

the said Massey had a wife, who was a very tall

woman, with blue eyes, chest nut-colored hair,

and a very bad temper; that, conjointly,

Massey and his wife were in the habit of

meting out cruel punishment to their slaves,

without regard to age or sex, and that they

themselves, ( Anna Elizabeth and

Sarah Jane), had received repeated

scourgings at the hands of their master.

Anna and Sarah were respectively

twenty-four and twenty-five years of age;

Anna was of a dark chestnut color, while

Sarah was two shades lighter; both had good

manners, and a fair share of intelligence, which

afforded a hopeful future for them in freedom.

Each had a babe in her arms.

SARAH had been a married woman for three years; her

child, a boy, was eight months old, and was

named Garrett Bell.

Elizabeth's child was a girl, nineteen

months old, and named Sarah Catharine Young.

Elizabeth had never been married.

They had lived with Massey five years up

to the last March prior to their escape, having

been bought out of the Balti-

[Page 508]

more slave-pen, with the understanding that they were to

be free at the expiration of five years' service under

him. The five years had more than expired, but no

hope or sign of freedom appeared. On the other

hand, Massey was talking loudly of selling them

again. Threats and fears were so horrifying to

them, that they could not stand it; this was what

prompted them to flee. “As often as six or seven

times," said Elizabeth, “I have been whipped by

master, once with the carriage whip, and at other times

with a raw hide trace. The last flogging I

received from him, was about four weeks before last

Christmas; he then tied me up to a locust tree standing

before the door, and whipped me to his satisfaction."

SARAH had

fared no better than Elizabeth, according to her

testimony. “Three times,” said she, “I have been

tied up; the last time was in planting corn-time, this

year. My clothing was all stripped off above my

waist, and then he whipped me till the blood ran down to

my heels.” Her back was lacerated all over.

She had been ploughing with two horses, and un

fortunately had lost a hook out of her plough; this, she

declared was the head and front of her offending,

nothing more. Thus, after all their suffering,

utterly penniless, they reached the Committee, and were

in every respect, in a situation to call for the deepest

commiseration. They were helped and were thankful.

_______________

ARRIVAL FROM

MARYLAND, VIRGINIA, AND THE DISTRICT OF

COLUMBIA.

JOHN WESLEY SMITH, ROBERT

MURRAY, SUSAN STEWART, AND JOSEPHINE SMITH.

Daniel Hubert was fattening on John

Wesley's earnings contrary to his, John's,

idea of right. For a long time John failed

to see the remedy, but as he grew older and wiser the

scales fell from his eyes and he perceived that the

Underground Rail Road ran near his master's place,

Cambridge, Md., and by a very little effort and a large

degree of courage and perseverance he might manage to

get out of Maryland and on to Canada, where

slave-holders had no more rights than other people.

These reflections came seriously into John's mind

at about the age of twenty-six; being about this time

threatened with the auction-block he bade slavery good

-night, jumped into the Underground Rail Road car and

off he hurried for Pennsylvania. His mother,

Betsy, one brother, and one sister were left in the

hands of Hubert. John Wesley

could pray for them and wish them well, but nothing

more.

ROBERT MURRAY

became troubled in mind about his freedom while living

in Loudon county, Virginia, under the heel of Eliza

Brooks, a widow woman, who used him bad,

according to his testimony. He had been

[Page 509]

“knocked about a good deal.” A short while before

he fled, he stated that he had been beat brutally, so

much so that the idea of escape was beat into him.

He had never before felt as if he dared hope to try to

get out of bondage, but since then his mind had

undergone such a sudden and powerful change, he began to

feel that nothing could hold him in Virginia; the place

became hateful to him. He looked upon a

slave-holder as a kind of a living, walking, talking

“Satan, going about as a roaring lion seeking whom he

may destroy.” He left his wife, with one child;

her name was Nancy Jane, and the name of

the offspring was Elizabeth. As Robert

had possessed but rare privileges to visit his wife, he

felt it less a trial to leave than if it had been

otherwise. William Seedam owned the

wife and child.

SUSAN STEWART and JOSEPHINE SMITH

fled together from the District of

Columbia. Running away had been for a long time a

favorite idea with Susan, as she had suffered

much at the hands of different masters. The main

cause of her flight was to keep from being sold again;

for she had been recently threatened by Henry

Harley, who "followed droving," and not being rich,

at any time when he might be in want of money she felt

that she might have to go. When a girl only twelve

years of age, her young mind strongly revolted against

being a slave, and at that youthful period she tried her

fortune at running away. While she was never

caught by her owners, she had the misfortune to fall

into the hands of another slave holder no better than

her old master, indeed she thought that she found it

even worse under him, so far as severe floggings were

concerned. Susan was of a bright brown

color, medium size, quick and active intellectually and

physically, and although she had suffered much from

Slavery, as she was not far advanced in years, she might

still do something for herself. She left no near

kin that she was aware of.

JOSEPHINE fled from Miss

Anna Maria Warren, who had

previously been deranged from the effects of paralysis.

Josephine regarded this period of her mistress'

sickness as her opportunity for planning to get away

before her mistress came to her senses.

_______________

SUNDRY ARRIVAL FROM MARYLAND AND VIRGINIA.

HENRY FIELDS, CHARLES

RINGGOLD, WILLIAM RINGGOLD, ISAAC NEWTON AND

JOSEPH THOMAS.

["Five other cases were attended to by

Dillwyn Parish and J. C. White" -

other than this no note was made of them.]

HENRY FIELDS took the benefit of the

Underground Rail Road at the age of eighteen.

He fled from the neighborhood of Port Deposit

while being "broke in" by a man named

Washington Glasby who was wicked

[Page 510]

enough to claim him as his

property, and was also about to sell him.

This chattel was of a light yellow complexion,

hearty-looking and wide awake.

CHARLES RINGGOLD took offence at being

whipped like a dog, and the prospect of being

sold further South; consequently in a high state

of mental dread of the peculiar institution, he

concluded that freedom was worth suffering for,

and although he was as het under twenty years of

age, he determined not to remain in

Perrymanville, Maryland, to wear the chains of

Slavery for the especial benefit of his

slave-holding master (whose name was

inadvertently omitted).

WILLIAM RINGGOLD

fled from Henry Wallace, of Baltimore.

A part of the time William said he "had

had it pretty rough, and a part of the time

kinder smooth," but never had had matters to his

satisfaction. Just before deciding to make

an adventure on the Underground Rail Road, his

owner had been talking of selling him.

Under the apprehension that this threat would

prove no joke, Henry began to study what

he had better do to be saved from the jaws of

hungry negro traders. It was not long

before he came to the conclusion that he had

best strike out upon a venture in a Northern

direction, and do the best he could to get as

far away as possible from the impending danger

threatened by Mr. Wallace. After a

long and weary travel on foot by night, he found

himself at Columbia, where friends of the

Underground Rail Road assisted him on to

Philadelphia. Here his necessary wants

were met, and directions given him how to reach

the land of refuge, where he would be out of the

way of all slave-holders and slave-traders.

Six of his brothers had been sold; his mother

was still in bondage in Baltimore.

ISAAC NEWTON

hailed from Richmond, Virginia. He

professed to be only thirty years of age, but he

seemed to be much older. while he had had

an easy time in slavery, he preferred that his

master should work for himself, as he felt that

it was his bounden duty to look after number

one; so he did not hesitate about leaving his

situation vacant for any one who might desire

it, whether white or black, but made a

successful "took out."

JOSEPH THOMAS

was doing the work of a so-called master in

Prince George's county, Maryland. For some

cause or other the alarm of the auction-block

was sounded in his ears, which at first

distracted him greatly; upon sober reflection it

worked greatly to his advantage. It set

him to thinking seriously on the subject of

immediate emancipation, and what a miserable

hard lot of it he should have through life if he

did not "pick up" courage and resolution to get

beyond the terror of slave-holders; so under

these reflections he found his nerves gathering

strength, his fears leaving him, and he was

ready to venture on the Underground Rail Road.

He came through without any serious difficulty.

He left his father and mother,

Shadrach and

Lucinda Thomas. [Page 511]

ARRIVAL FROM

SEAFORD, 1859

ROBERT BELL AND TWO OTHERS.

ROBERT

came from

Seaford, where he had served under Charles Wright,

a farmer, of considerable means, and the owner of a

number of slaves over whom he was accustomed to rule

with much rigor.

Although Robert's master had a wife and five

children, the love which Robert bore them was too

weak to hold him; and well adapted as the system of

Slavery might be to render him happy in the service of

young and old masters, it was insufficient for him.

Robert found no rest under Mr. Wright; no

privileges, scantily clad, poor food, and a heavy yoke,

was the policy of this "superior." Robert

testified, that for the last five years, matters had

been growing worse and worse; that times had never been

so bad before. Of nights, under the new regime,

the slaves were locked up and not allowed to go

anywhere; flogging, selling, etc. were the every-day

occurrence throughout the neighborhood. Finally,

Robert became sick of such treatment, and he

found that the spirit of Canada and freedom was

uppermost in his heart. Slavery grew blacker and

blacker, until he resolved to "pull up stakes" upon a

venture. The motion was right, and succeeded.

Two other passengers were at teh station at the same

time, but they had to be forwarded without being

otherwise noticed on the book.

_______________

ARRIVAL FROM TAPP'S NECK, MD., 1859.

LEWIS WILSON, JOHN WATERS, ALFRED EDWARDS

AND WILLIAM QUINN.

LEWIS' grey hairs signified

that he had been for many years plodding under the yoke.

He was about fifty years of age, well set, not tall, but

he had about him the marks of a substantial laborer.

He had been brought up on a farm under H. Lynch,

whom Lewis described as "a mean man when drunk,

and very severe on his slaves." The number that he

ruled over as his property, was about twenty. Said

Lewis, about two years ago, he shot a free man,

and the man died about two hours afterwards; for this

offence he was ot even imprisoned. Lynch

also tried to cut the throat of John Waters, and

succeeded in making a frightful gash on his left

shoulder (mark shown), which mark he will carry with him

to the grave; for this he was not even sued.

Lewis left five children in bondage, Horace,

John, georgians, Louisa and Louis, Jr., owned

by Bazil and John Benson.

[Page 512]

JOHN was forty years of age, dark, medium size,

and another of Lynch's "articles." He left

his wife Anna, but no children; it was hard to

leave her, but he felt that it would be still harder to

live and die under the usage that he had experienced on

Lynch's farm.

ALFRED was twenty-two years of

age; he was of a full dark color, and quite smart.

He fled from John Bryant, a farmer. Whether

he deserved it or not, Alfred gave him a bad

character, at least, with regard to the treatment of his

slaves. He left his father and mother, six

brothers and sisters. Traveling under doubts and

fears with the thought of leaving a large family of his

nearest and dearest friends, was far from being a

pleasant undertaking with Alfred, yet he bore up

under the trial and arrived in peace.

"WILLIAM

is twenty-two,

black, tall, intelligent, and active," are the words of

the record.

_______________

ARRIVAL FROM

MARYLAND, 1859.

ANN MARIA JACKSON AND HER SEVEN CHILDREN

- MARY ANN, WILLIAM HENRY, FRANCES SABRINA,

WILHELMINA, JOHN EDWIN, EBENEZER THOMAS, AND

WILLIAM ALBERT

The coming of the above named was duly

announced by Thomas Garrett:

| |

|

WILMINGTON, 11th mo., 21st, 1858 |

DEAR FRIENDS - McKIM and STILL: - I write to inform you

that on the 16th of this month, we passed on four able

bodied men to Pennsylvania, and they were followed last

night by a woman and her six children, from three or

four years of age, up to sixteen years; I believe

the whole belonged to the same estate, and they were to

have been sold at public sale, I was informed yesterday,

but preferred seeking their own master; we had some

trouble in getting those last safe along, as they could

not travel far on foot, and could not

[Page 513]

safely cross any of the bridges on the canal, either on

foot or in carriage. A man left here two days

since, with carriage, to meet them this side of the

canal, but owing to spies they did not reach him till 10

o'clock last night; this morning he returned, having

seen them about one or two o'clock this morning in a

second carriage, on the border of Chester county, where

I think they are all safe, if they can be kept from

Philadelphia If you see them they can tell their

own tales, as I have seen one of them. May He, who

feeds the ravens, care for them. Yours,

The fire of

freedom obviously burned with no ordinary fervor in the

breast of this slave mother, or she never would have

ventured with the burden of seven children, to escape

from the hell of Slavery.

ANN MARIA was about forty years

of age, good-looking, pleasant countenance, and of a

chestnut color, height medium, and intellect above the

average. Her bearing has humble, as might have

been expected, from the fact that she emerged from the

lowest depths of Delaware Slavery. During the Fall

prior to her escape, she lost her husband under most

trying circumstances; he died in the poor-house, a

raving maniac. Two of his children had been taken

from their mother by her owner, as was usual with

slave-holders, which preyed so severely on the poor

father's mind that it drove him into the state of

hopeless insanity. He was a "free man" in the eye

of Delaware laws, yet he was not allowed to exercise the

least authority over his children.

Prior to the time that the two children were taken from

their mother, she had been allowed to live with her

husband and children, independently of her master, by

supporting herself and them with the white-wash brush,

wash-tub, etc. For this privilege the mother

doubtless worked with double energy, and the master, in

all probability, was largely the gainer, as the children

were no expense to him in their infancy; but when they

began to be old enough to hire out, or bring high prices

in the market, he snatched away two of the finest

articles and the powerless father was immediately

rendered a fit subject for the mad-house; but eh brave

hearted mother looked up to God, resolved to wait

patiently until in a good Providence the way might open

to escape with her remaining children to Canada.

Year in and year out she had suffered to provide food

and raiment for her little ones. Many times in

going out to do days' work she would be compelled to

leave her children, not knowing whether during her

absence they would fall victims to fire, or be carried

off by the master. But she possessed a well tried

faith, which in her flight kept her from despondency.

Under her former lot she scarcely murmured, but declared

that she had never been at east in Slavery a day after

the birth of her first-born. The desire to go to

some part of the world where she could have the control

and comfort of her children, had always been a

prevailing idea with her. "It almost broke my

heart," she said, "when he came and took my children

away as soon as they were big enough to hand me a drink

of water. My

[Page 514]

husband was always very kind to me, and I had often

wanted him to run away with me and the children, but I

could not get him in the notion; he did not feel that he

could, and so he stayed , and died broken-hearted,

crazy. I was owned by a man named Joseph

Brown; he owned property in Milford, and he had a

place in Vicksburg, and some of his time he spends

there, and some of the time he lives in Milford.

This Fall he said he was going to take four of my oldest

children and two other servants to Vicksburg. I

just happened to hear of this news in time. My

master was wanting to keep me in the dark about taking

them, for fear that something might happen. My

master is very sly; he is a tall, slim man, with a

smooth face, bald head, light hair, long and sharp nose,

swears very hard, and drinks. He is a widower, and

is rich.

On the road the poor mother, with her travel -

worn children became des perately alarmed, fearing that

they were betrayed. But God had provided better things

for her ; her strength and hope were soon fully

restored, and she was lucky enough to fall into the

right hands. It was a special pleasure to aid such a

mother. Her arrival in Canada was announced by Rev. H.

Wilson as follows:

| |

|

NIAGARA CITY, Nov. 30th, 1858. |

DEAR BRO. STILL : - I am happy to inform you that

Mrs. Jackson and her interesting family of seven

children arrived safe and in good health and spirits at

my house in St. Catharines, on Saturday evening last.

With sincere pleasure I provided for them comfort able

quarters till this morning, when they left for Toronto.

I got them conveyed there at half fare, and gave them

letters of introduction to Thomas Henning, Esq.,

and Mrs. Dr. Willis, trusting that they will be

better cared for in Toronto than they could be at St.

Catharines. We have so many coming to us we think

it, best for some of them to pass on to other places.

My wife gave them all a good supply of clothing before

they left us. James Henry, an older

son is, I think, not far from St. Catharine, but has not

as yet reunited with the family. Faithfully and truly

yours,

| |

Faithfully and truly yours, |

HIRAM WILSON . |

_______________

SUNDRY

ARRIVALS FROM VIRGINIA, MARYLAND AND DELAWARE.

LEWIS LEE, ENOCH DAVIS, JOHN BROWN,

THOMAS EDWARD DIXON, AND WILLIAM OLIVER.

Slavery brought about many radical changes, some in one

way and some in another. Lewis Lee

was entirely too white for practical purposes.

They tried to get him to content himself under the yoke,

but he could not see the point. A man by the name

of William Watkins, living near Fairfax,

Virginia, claimed Lewis, having come by his title

through marriage. Title or no title, Lewis

thought that he would not serve him for nothing, and

that he had been hoodwinked already a great while longer

than he should have allowed himself to be.

Watkins had managed to keep him in the dark and

[Page 515]

doing hard work on the no-pay system up to the age of

twenty-five. In Lewis’ opinion, it was now

time to “strike out on his own hook;” he took his last

look of Watkins (he was a tall, slim fellow, a

farmer, and a hard drinker), and made the first step in

the direction of the North. He was sure that he

was about as white as anybody else, and that he had as

good a right to pass for white as the white folks, so he

decided to do so with a high head and a fearless front.

Instead of skulking in the woods, in thickets and

swamps, under cover of the darkness, he would boldly

approach a hotel and call for accommodations, as any

other southern gentleman. He had a little money,

and he soon discovered that his color was perfectly

orthodox. He said that he was “treated first-rate

in Washington and Baltimore;" he could recommend both of

these cities. But destitute of education, and

coming among strangers, he was conscious that the shreds

of slavery were still to be seen upon him. He had,

moreover, no intention of disowning his origin when once

he could feel safe in assuming his true status. So

as he was in need of friends and material aid, he sought

out the Vigilance Committee, and on close examination

they had every reason to believe his story throughout,

and gave him the usual benefit.

ENOCH DAVIS

came from within five miles of Baltimore, having been

held by one James Armstrong, "an old grey-headed

man," and a farmer, living on Huxtown Road. Judged

from Davis' stand-point, the old master could

never been recommended, unless some one wanted a very

hard place and a severe master. Upon inquiry, it

was ascertained that Enoch was moved to leave on

account of the "riot," (John Brown's Harper's

Ferry raid), which he feared would result in the sale of

a good many slaves, himself among the number,; he,

therefore, "laid down the shovel and the hoe," and quit

the place.

JOHN BROWN

(this was an adopted name, the original one not being

preserved), left to get rid of his connection with

Thomas Stevens, a grocer, living in Baltimore.

John, however, did not live in the city with said

Stevens, but on the farm near Frederick's Mills,

Montgomery county, Maryland. This place was known

by the name of "White Hall Farm;" and was under the

supervision of James Edward Stevens, a son of the

above-named Stevens. John's reason s for

leaving were not noted on the book, but his eagerness to

reach Canada spoke louder than words, signifying that

the greater the distance that separated him from the old

"White Hall Farm" the letter.

THOMAS EDWARD DIXON

arrived from near the Trap, in Delaware. He was

only about eighteen eyars of age, but as tall as a man

of ordinary height; - dark, with a pleasant countenance.

He reported that he had had trouble with a man known by

the name of Thomas W. M. McCracken, who had

treated him "bad;" as Thomas thought that such

trouble and bad treatment might be of frequent

occurrence, he concluded that he had better go

[Page 516]

away and let McCracken get somebody else to fill his place,

if he did not choose to fill it himself. So off Thomas

started, and as if by instinct, he came direct to the Committee.

He passed a good examination and was sided.

WILLIAM

OLIVER, dark, well-made, young man with

the best of country manners, fled from Mrs. Marshall, a lady living in Prince

George's county, Maryland. William had recently been in

the habit of hiring his time at the rate of ten dollars per month,

and find himself everything. The privilege of living in

Georgetown had been vouchsafed him, and he preferred this locality

to his country situation. Upon the whole he said he had been

treated pretty well. He was, nevertheless, afraid that times

were growing "very critical," and as he had a pretty good chance, he

thought he had better make use of it, and his arrangements were

wisely made. He had reached his twenty-sixty year, and was

apparently well settled. He left one child, Jane Oliver

owned by Mrs. Marshall.

_______________

ARRIVAL

FROM DIFFERENT POINTS

JACOB BROWN, JAMES HARRIS, BENJAMIN PINEY, JOHN

SMITH, ANDREW JACKSON, WILLIAM HUGHES, WESLEY WILLIAMS, ROSANNA

JOHNSON, JOHN SMALLWOOD, AND HENRY TOWNSEND.

JACOB BROWN was eating the

bread of Slavery in North Carolina. A name-sake of his by the

name of Lewis Brown, living in Washington, according to the

slave code of that city had Jacob in fetters, and was

exercising about the same control over him that he exercised over

cattle and horses. While this might have been a pleasure for

the master, it was painful for the slave. The usage which

Jacob had ordinarily received made him anything but contented.

At the age of twenty, he resolved that he would run

away if it cost him his life. This purpose was made known to a

captain, who was in the habit of bringing passengers from the South

to Philadelphia. With an unwavering faith he took his

appointed place in a private part of the vessel, and as fast as wind

and tide would bring the boat he was wafted on his way Canada-ward.

Jacob was a dark man, and about full size, with hope large.

JAMES

HARRIS

escaped from Delaware. A white woman,

Catharine Odine by name, living near Middletown, claimed

James as her man; but James did not care to work for her on

the unrequited labor system. He resolved to take the first

train on the Underground Rail Road that might pass that way.

It was not a great while ere he was accommodated, and was brought

safely to Philadelphia. The regular examination was made and

he passed creditably. He was described in the book as a man of

yellow

[Page 517]

complexion, good-looking, and intelligent. After

due assistance, he was regularly forwarded on to canada.

This was in the mouth of November, 1856.

Afterwards nothing more was heard of him, until the

receipt of the following letter from Prof. L. D.

Mansfield, showing that he had been reunited to his

wife, under amusing, as well as touching circumstances:

DEAR BRO. STILL: - A very

pleasant circumstances has brought you to mind, and I am always

happy to be reminded of you, and of the very agreeable, though brief

acquaintance which he made at Philadelphia two years since.

Last Thursday evening, while at my weekly prayer meeting, our

exercises were interrupted by the appearance of Bro. Loguen,

of Syracuse, who had come on with Mrs. Harris in search of

her husband, whom he had sent to my care three weeks before. I

told Bro. L. that no such man had been at my house, and I

knew nothing of him. But I dismissed the meeting, and went

with him immediately to the African Church, where the collored

brethren were holding a meeting. Bro. L. looked through

the dor, and the first person whom he saw was Harris.

He was called out, when Loguen said, in a rather reproving

and excited tone, "What are you doing here; didn't I tell you to e

off to Canada? Don't you known they are after you? Come

get your hat, and come with us, we'll take care of you." The

poor fellow was by this time thoroughly frightened, and really

thought he had been pursued. We conducted him nearly a mile,

to the hotel where his wife was waiting for him, leaving him still

under the impression that he was pursued and that we were conducting

him to a place of safety, or were going to box him up to send hi to

Canada. Bro. L. opened the door of the parlor, and

introduced him; but he was so frightened that he did not know his

wife at first, until she called him James, when they had a

very joyful meeting. She is now a servant in y family, and he

has work, and doing well, and boards with her. We shall do all

we can for them, and teach them to read and write, and endeavor to

place them in a condition to take care of themselves.

Loguen had a fine meeting in my Tabernacle last night, and made

a good collection for the cause of the fugitives.

I should be happy to hear from you and your kind

family, to whom remember me very cordially. Believe me ever

truly yours,

L. D. MANSFIELD.

Mr. and Mrs. Harris wish to be

gratefully remembered to you and yours.

BENJAMIN

PINEY reported that he came from Baltimore

county, Maryland, where he had held in subjection to Mary

Hawkins. He alleged that he had very serious cause for

grievance; that she had ill-treated him for a long time and had of

late threatened to sell him to Georgia. His brothers and

sisters had all been sold, but he meant not to be if he could help

himself. The sufferings that he had been called upon to endure

had opened his eyes, and he stood still to wait for the Underground

Rail Road car, as he anxiously wished to travel north, with all

possible speed. He waited, but a little while, ere he was on

the road, under difficulties it is true, but he arrived safely and

was joyfully received. He imagined his mistress in a fit of

perplexity, such as he might enjoy, could he peep at her from

Canada, or some safe place. He however did not wish her any

evil, but he was very decided that he did not want any more to do

with her. Benjamin was twenty years of age, dark

complexion, size ordinary, mental capacity, good considering

opportunities.

[Page 518]

JOHN

SMITH

was a yellow boy, nineteen years of age, stout

build, with marked intelligence. He held Dr. Abraham Street

responsible for treating him as a slave. He held Dr.

Abraham Street responsible for treating him as a slave.

The doctor lived at Marshall District, Harford county, Maryland.

John frankly confessed, to the credit of the doctor, that he

got "a plenty to eat, drink and wear," yet he declared that he was

not willing to remain a slave, he had higher aims; he wanted to be

above that condition. "I left," said he, "because I wanted to

see the country. If he had kept me in a hogshead of sugar, I

wouldn't stayed," said the bright-minded slave youth. "They told me

anything - told me to obey my master, but I didn't mind that.

I am going off to see the Scriptures," said John.

ANDREW JACKSON

"took out" from near Cecil, Delaware, where he had been owned by a

man calling himself Thomas Palmer, who owned seven or eight

others. His manners were by no means agreeable to Andrew;

he was quite too "blustery," and was dangerous when in one of his

fits. Although Andrew was but twenty-three years of

age, he thought that Palmer had already had much more of his

valuable services than he was entitled to, and he determined, that

if he (the master), ever attempted to capture him, he would make him

remember him the longest day he lived.

WILLIAM HUGHES was an Eastern

Shore "piece of property" belonging to Daniel Cox. William

had seen much of the dark doings of Slavery, and his mind had

been thoroughly set against the system. True, he had been but

twenty-two years under the heel of his master, but that was

sufficient.

WESLEY WILLIAMS, on his arrival

from Warrick, Maryland, testified that he had been in the hands of a

man known by the name of Jack Jones, from whom he had

received almost daily floggings and scanty food. Jones

was his so-called owner. These continual scourgings stirred

the spirit of freedom in Wesley to that degree that he was compelled

to escape for his life. He left his mother (a free woman), and

one sister in Slavery.

ROSANNA JOHNSON, alias CATHARINE

BRICE.

The spot of Rosanna looked upon the most dread and where she

had suffered as a slave, under a man called Doctor Street,

was near the Rock of Deer Creek, in Harford county, Maryland.

In the darkness in which Slavery ordinarily kept the

fettered and "free niggers," it was a considerable length of time

ere Rosanna saw how barbarously she and her race were being

wronged and ground down - driven to do unrequited labor - deprived

of an education, obliged to receive the cuffs, kicks, and curses of

old or young, who might happen to claim a title to them. But

when she did see her true condition, she was not content until she

found herself on the Underground Rail Road.

Rosanna was about thirty years of age, of a dark

color, medium stature, and intelligent. She left two brothers

and her father behind. The Committee forwarded her on North.

From Albany Rose wrote back to inquire after particular

friends, and to thank those who had aided her - as follows:

[Page 519]

| |

|

ALBANY, Jan. the 30, 1858 |

MRS. WILLIAM STILL: -

i sit don to rite you a fue lines in saying have you herd of

John Smith or Benjamin Pina i have cent letters to

them but i hav know word from them John Smith was oned by

Doker abe Street Bengermin oned by Mary hawkings i wish

to know if you kno am if you will let me know as swon as you get

this. My lov to Mis Still i am much oblige for those

articles. My love to mrs. george and verry thankful to

her Rosean Johnson oned by doctor Street when you cend

the letter rite it Cend it 63 Gran St in the car of andrue