|

STILL'S

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORDS,

REVISED EDITION.

(Previously Published in 1879 with title: The Underground Railroad)

WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR.

NARRATING

THE HARDSHIPS, HAIRBREADTH ESCAPES AND DEATH STRUGGLES

OF THE

SLAVES

IN THEIR EFFORTS FOR FREEDOM.

TOGETHER WITH

SKETCHES OF SOME OF THE EMINENT FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, AND

MOST LIBERAL AIDERS AND ADVISERS OF THE ROAD

BY

WILLIAM STILL,

For many years connected with the Anti-Slavery Office in

Philadelphia, and Chairman of the Acting

Vigilant Committee of the Philadelphia Branch of the Underground

Rail Road.

Illustrated with 70 Fine Engravings

by Bensell, Schell and Others,

and Portraits from Photographs from Life.

Thou shalt not deliver unto his

master the servant that has escaped from his master unto thee. -

Deut. xxiii 16.

SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION.

PHILADELPHIA:

WILLIAM STILL, PUBLISHER

244 SOUTH TWELFTH STREET.

1886

pp. 642 - 654

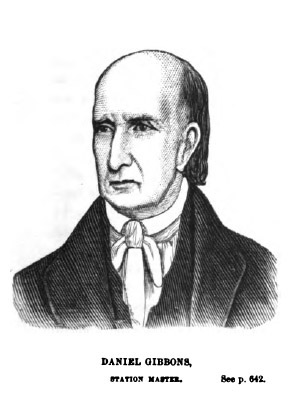

DANIEL GIBBONS.

Page 642

A life as uneventful as the one whose story we are about

to tell, affords little scope for the genius of the

biographer or the historian, but being carefully

studied, it cannot fail to teach a lesson of devotion

and self-sacrifice, which should be learned and

remembered by every succeeding age.

Daniel Gibbons, son of James and Deborah

(Hoopes) Gibbons, wa sborn on the banks of Mill

creek, in Lancaster county, Pennsylvania, on the 21st

day of the 12th month (December), 1775. He was

descended on his father's side from an English ancestor,

whose name appears on the colonial records, as far back

as 1683. John Gibbons evidently came with

or before William Penn to this "goodly heritage

of freedom." His earthly remains lie at Concord

Friends' burying-ground, Delaware county, near where the

family lived for a generation or two. The

grandfather of Daniel Gibbons, who lived near

where West Town boarding-school now is, in Chester

county, bought for seventy pounds, "one thousand acres

of land and allowances," in what is now Lancaster

county, intending, as he ultimately did, to settle his

three sons upon it. This purchase was made about

the year 1715. In process of time, the

eldest son, desiring to marry Deborah Hoopes, the

daughter of Daniel Hoopes, of a neighboring

township in Chester county, the young people obtained

the consent of parents and friends, but it was a time of

grief and mourning among young and old. The young

Friends assured the intended bride, that they would not

marry the best man in the Province and do what she was

about to do; and the elder dames, so far relaxed the

Puritanic rigidity of their rules, as to allow the

invitation of an uncommonly large company of guests to

the wedding, in order that a long and perhaps last

farewell, might be said to the beloved daughter, who,

with her husband, was about to emigrate to the "far

West." Loud and long were the lamentations, and

warm the embraces of these simple minded Christian

rustics, companions of toil and deprivation, as they

parted from two of their number who were to leave their

circle for the West; the West being then thirty-six

miles distant. This was on the sixth day of the

fifth month, 1756. More than a century has passed

away; all the good people, eighty-nine in number, who

signed the wedding certificate as witnesses, have passed

away, and how vast is the change wrought in our midst

since that day!

Joseph Gibbons was so much pleased with the

daring enterprise of his son and daughter-in-law, that

he gave them one hundred acres of land in his Western

possessions more than he reserved for his other and

younger sons, and to it they immediately emigrated, and

building first a cabin and the next year a store-house,

began life for themselves in earnest.

It is interesting, in view of the long and consistent

anti-slavery course

[pg. 643]

which Daniel Gibbons pursued, to trace the

influence that wrought upon him while his character was

maturing, and the causes which led him to see the

wickedness of the system which he opposed.

The Society of Friends in that day bore in mind the

advice of their great founder, Fox, whose last

words were: "Friends, mind the light." And

following that guide which leads out of all evil and

into all good, they viewed every custom of society with

eyes undimmed by prejudice, and were influenced in every

action of life by a belief in the common brother hood of

man, and a resolve to obey the command of Jesus, to love

one another. This being the case, slavery and

oppression of all kinds were unpopular, and indeed

almost unknown amongst them.

James Gibbons was a republican, and an

enthusiastic advocate of American liberty. Being a

man of commanding presence, and great energy and

determination, efforts were made during the Revolution

to induce him to enlist as a cavalry soldier. He

was prevented from so doing by the entreaties of his

wife, and his own conscientious scruples as a Friend.

About the time of the Revolution, or immediately after,

he removed to the borough of Wilmington, Delaware,

where, being surrounded by slavery, he became more than

ever alive to its iniquities. He was interested

during his whole life in getting slaves off. And

being elected second burgess of Wilmington during his

residence there, his official position gave him great

opportunities to assist in this noble work. It is

related that during his magistracy a slave-holder

brought a colored man before him, whom he claimed as his

slave. There being no evidence of the alleged

ownership, the colored man was set at liberty. The

pretended owner was inclined to be impudent; but

James Gibbons told him promptly that nothing

but silence and good behaviour on his part would prevent

his commitment for contempt of court.

About the year 1790, James Gibbons came

back to Lancaster county, where he spent twenty years in

the practice of those deeds which will remain "in

everlasting remembrance;" dying, full of years and

honors, in 1810.

Born in the first year of the revolution and growing up

surrounded by such influences, Daniel Gibbons

could not have been other than he was, the friend of the

down-trodden and oppressed of every nationality and

color. In 1789 his father took him to see General

Washington, then passing through Wilmington.

To the end of his life he retained a vivid recollection

of this visit, and would recount its incidents to his

family and friends. During his father's residence

in Wilmington, he spent his summers with kinsmen in

Lancaster county, learning to be a farmer, and his

winters in Wilmington going to school.

At the age of fourteen years he was bound an

apprentice, as was the good custom of the day, to a

Friend in Lancaster county to learn the tanning

business. At this he served about six years, or

until his master ceased to follow the business.

During this apprenticeship he became accustomed to

[pg. 644]

severe labor, so severe indeed that he never recovered

from the effects thereof, having a difficulty in walking

during the remainder of his life, which prevented him

from taking the active part in Underground Rail Road

business which he otherwise would have done. His

father’s estate being involved in litigation caused him

to be put to this trade, farming being his favorite

employment, and one which he followed during his whole

life.

In 1805 he took a pedestrian tour, by way of New York,

Albany, and Niagara Falls to the State of Ohio, then the

farm West, coming home by way of Pittsburg, and walking

altogether one thousand three hundred and fifty miles.

In this trip he increased the injury to his feet, so as

to render himself virtually a cripple. Upon the

death of his father he settled upon the farm, on which

he died.

About the year 1808 on going to visit some friends, who

has removed to Adams county, Pennsylvania, he became acquanted

with Hanna Wierman, whom he married on the fourth

day of the fifth month, 1815. At this time

Daniel Gibbons was about forty years old, and his

wife about twenty-eight, she having been born on the

ninth of the seventh month, 1787. A life of one

after their union, would be incomplete without

some notice of the other.

During a married life of thirty-seven years, Hannah

Gibbons was the assistant of her husband in every

good and noble work. Possessed of a warm heart, a

powerful, though uncultivated intellect, an excellent

judgment, and great sweetness of disposition, she was

fitted both by nature and training to endure without

murmuring the inconvenience of trouble incident to the

reception and care of fugitives and to rejoice that to

her was given the opportunity of assisting them in their

efforts to be free.

The true measure of greatness in a human soul, is its

willingness to suffer for its own good, or the good of

its fellows, its self-sacrificing spirit. Granting

the truth of this, one of the greatest souls was that of

Hannah W. Gibbins. The following incident

is a proof of this:

In 1836, when she was no longer a young woman, thee

came to her home, one of the poorest, most ignorant, and

filthiest of mankind. - a slave from the great valley of

Virginia. He was foot-sore and weary, and could

not tell how he came, or who directed him. He

seemed indeed, a missive directed and set by the hand of

the almighty. Before he could be cleansed or

recruited, he was taken sick, and before he could be

removed (even if he could have been trusted at the

county poor house), his case was pronounced to be

small-pox. For six long weeks did this good angel

in human form, attend upon this unfortunate object.

reasons were found why no one else could do it, and with

her own hands, she ministered to his wants, until he was

restored to health. Such was her life. This

is merely one case. She was always ready to do her

duty. Her interest in good, never left her, for

when almost dying, she aroused from her lethargy and

asked if Abraham Lincoln was elected president of

the United States, which he was a few days after

[pg. 645]

wards. She always predicted a civil war, in the

settlement of the Slavery question.

During the last twenty-five years of her life she was

an elder in the Society of Friends, of which she had

always been an earnest, consistent, and devoted member.

Her patience, self-denial, and warm affection were

manifested in every relation of life. As a

daughter, wife, mother, friend, and mistress of a family

she was beloved by all, and to her relatives and friends

who are left behind, the remembrance of her good deeds

comes wafted like a perfume from beyond the golden

gates. She survived her husband about eight years,

dying on the sixteenth of the tenth month, 1860.

Three children, sons, were born to their marriage, two

of whom died in infancy and one still (1871) survives.

To give some idea of the course pursued by Daniel

and Hannah Gibbons, I insert the following letter,

containing an account of events which took place in

1821:

"A short time since, I learned that my old friend,

William Still was about to publish a history of the

Underground Rail Road. His own experience in the

service of this road would make a large volume. I

was brought up by Daniel Gibbons, and am asked to

say what I know of him as an abolitionist. From my

earliest recollection, he was a friend to the colored

people, and often hired them and paid them liberal

wages. His house was a depot for fugitives, and

many hundreds has he helped on their way to freedom.

Many a dark night he has sent me to carry them victuals

and change their places of refuge, and take them to

other people's barns, when not safe for him to go.

I have known him start in the night and go fifty miles

with them, when they were very hotly pursued. One

man and his wife lived with him for a long time.

Afterwards to man lived with Thornton Walton.

The man was hauling lumber from Columbia. He was

taken from his team in Lancaster, and lodged in

Baltimore jail. Daniel Gibbons went to

Baltimore, visited the jail and tried hard to get him

released, but failed. I would add here, that

Daniel Gibbons faithful wife, one of the best women

I ever knew, was always ready, day or night, to do all

she possibly could to help the poor fugitives on their

way to freedom. Many interesting incidents

occurred at the home of my uncle. I will relate

one. He had living with him at one time, two

colored men, Thomas Colbert and John

Stewart. The latter was from Maryland;

John often said he would go back and get his wife.

He said no, for his master knew if he undertook to take

him, he would kill him. He did go and brought his

wife to my uncle's.

While these two large men, Tom and John,

were there along came Robert (other name unknown), and

in bad plight, his feet bleeding. Robert

was put in the barn to thrash, until he could be fixed

up to go again on his

[pg. 646]

journey. But in a few days, behold, along came his

master. He brought with him that notorious

constable, Haines, from Lancaster, and one other

man. They came suddenly upon Robert; as

soon as he saw them he ran and jumped out of the

"overshoot," some ten feet down. In jumping, he

put one knee out of joint. The men ran around the

barn and seized him. By this time, the two colored

men, Tom and John, came, together with my

uncle and aunt. Poor Robert owned his

master, but John told them they should not take

him away, and was going at them with a club. One

of the men drew a pistol to shoot John, but uncle

told him he had better not shoot him; this was not a

slave State. Inasmuch as Robert had owned

his master, Uncle told John h must submit, so

they put Robert on a horse, and started with him.

After they were gone John said: "Mr. Gibbons,

just say the word, and I will bring Robert back."

Aunt said: "Go, John, go!" So John

ran to Joseph Rakestraw's and got a gun (without

any lock), and ran across the fields, with Tom after

him, and headed the party. The men all ran

except Haines, who kept Robert between

himself and John, so that John should not

shoot him. But John called out to Robert

to drop off that horse or he would shoot him. This

Robert did, and John and Tom

brought him back in triumph. My aunt said:

"John, thee is a good fellow, thee has done well."

Robert was taken to Jesse Gilberts barn,

and Dr. Dingee fixed his knee. As Soon as

he was able to travel, he took a "bee-line" for the

North star.

My life with my uncle and aunt made me an abolitionist.

I left them in the winter of 1824 and came to Salem,

Ohio, where I kept a small station on the Underground

Rail Road, until the United States government took my

work away. I have helped over two hundred

fugitives on their way to Canada.

Respectfully,

DANIEL BONSALL,

Salem, Columbiana county, Ohio."

One day, in the winter of

1822, Thomas Johnson, a colored man, living with Daniel

Gibbons, went out early in the morning, to set traps for

muskrats. While he was gone, a slave-holder came to the house

and inquired for his slave. Daniel Gibbons said: "There

is no slave here of that name." The man replied: "I know he is

here. The man we're after, is a miserable, worthless, thieving

scoundrel.' "Oh! very well, then," said the good Quaker, "if

that's the kind of man thee's after, then I know he is not here.

We have a colored man here, but he is not that kind of a man."

The slave-holder waited awhile, the man not making his appearance,

then said: "Well, now, Mr. Gibbons, when you see that man

next, tell him that we were here, and if he will come home, we will

take good care of him, and be kind to him." "Very well," said

Daniel, "I will tell him what thee says, but say to him at

the same time, that he is a very great fool, if he does as thee

requests." The colored man sought, having caught sight of the

slave-

[pg. 647]

holders, and knowing who they were, went off that night,

under Daniel Gibbons' directions, and was never

seen by his master gain. Afterward, Daniel

and his nephew, William Gibbons, went with this

man to Adams county. With his master came the

master of Mary, a girl with straight hair, and

nearly white, who lived with Daniel Gibbons and

his wife. Poor Mary was unfortunate.

Her master caught her, and took her back with him into

Slavery. She and a little girl, who was taken away

about the year 1830, were the only ones ever taken back

from the house of Daniel Gibbons.

Between the time of his

marriage, when he began to keep a depot on the

Underground Rail Road, and the year 1824, he passed more

than one hundred slaves through to Canada, and between

the latter time and his death, eight hundred more,

making, in all nine hundred aided by him. He was

ever willing to sacrifice his own personal comfort and

convenience, in order to assist fugitives. In

1833, when on his way to the West, in a carriage with

his friend, Thomas Peart, also a most faithful

friend of the colored man and interested in Underground

Rail Road affairs, he found a fugitive slave, a woman,

in Adams county, who was in immediate danger. He

stopped his journey, and sent his horse and wagon back

to his own home with the woman, that being the only safe

way of getting her off. This was but a sample of

his self-denial, in the cause of human freedom.

His want of ability to guide in person runaway slaves,

or to travel with them, prevented him from taking active

part in the wonderful adventures and hair-breadth

escapes which his brain and tact rendered possible and

successful. It is believed that no slave was ever

recaptured that followed his directions. Sometimes

the abolitionists were much annoyed by impostors, who

pretended to be runaways, in order to discover their

plans, and betray them to the slave-holders.

Daniel Gibbons was possessed of much acuteness in

detecting these people, but having detected them, he

never treated them harshly or unkindly.

Almost from infancy, he was distinguished for the

gravity of his deportment, and his utter heedlessness of

small things. The writer has heard men preach the

doctrine of the trifling value of the things of a

present time, and of the tremendous importance of those

of a never-ending eternity, but Daniel Gibbons is

the only person she ever knew, who lived that doctrine.

He believed in plainness of apparel as taught by

Friends, not as a form or a rule of society, but as a

principle; often quoting from some one who said that

"The adornment of a vain and foolish world, would feed a

starving one." He opposed extravagant fashions and

all luxury of habit and life, as calculated to produce

effeminacy and degrading sensuality, and as a bestowal

of idolatrous attention upon that body which he would

often say "was here but for a shore time."

Looking only upon that as religion, which made men love

each other and do good to each other in this world, he

was little of a stickler for points of

[pg. 648]

belief, and even when he did look into theological

matters or denounce a man's religious opinions, it was

generally because they were calculated to darken the

mind and be entertained as a substitute for good works.

Pursuing the even tenor of his way, he could as easily

lead the flying fugitive slave by night out of the way

of his powerful master, as one differently constituted

could bestow his wealth upon the most popular charity in

the land.

His faith was of the simplest kind - the Parable of the

prodigal son, contains his creed. Discarding what

are commonly called "plans of salvation," he believed in

the light "which lighteth every man that cometh into the

world," and that if people would follow this light, they

would thus seek "the kingdom of Heaven and its

righteousness and all other things needful would be

added thereunto. He was a devoted member of the

Society of Friends, in which he held the position of

elder, during the last twenty-five years of his life.

That peculiar doctrine of the Society, which repudiates

systematic divinity and with it a paid ministry, he held

in special reverence, finding confirmation of its truth

in the general advocacy of Slavery, by the popular

clergy of his day.

When he was quite advanced in years, and the

Anti-slavery agitation grew war, he was solicited to

join an anti-slavery society, but on hearing the

constitution read, and finding that it repudiated all

use of physical force on the part of the oppressed in

gaining their liberty, he said that he could not assent

to that - that he had long been engaged in getting off

slaves, and that he had always advised them to use

force, although remonstrating against going to the

extent of taking life, and that now he could not recede

from that position, and he did not see how they could

always be got off without the use of some force.

His faith is an overruling Providence was complete.

He believed, even in the darkest days of freedom in our

land, in the ultimate extinction of Slavery, and at

times, although advanced in year, thought he would live

to witness that glorious consummation. It is only

in a man's own family and by his wife and children, that

he is really known, and it is by those who best knew,

and indeed, who only knew this good man, that his

biographer is most anxious that he should be judged.

As a parent, he was not excessively indulgent, as a

husband, one more nearly a model is rarely found.

But his kindness in domestic life, his love for his

wife, his son and his grandchildren, and their

reciprocal love and affection for him, no words can

express.

It was in his father's household in his youth and in

his own household in his mature years, that was fostered

that wealth of love and affection, which, extending and

widening, took in the whole race, and made him the

friend of the oppressed everywhere, and especially of

those whom it was a dangerous and unpopular task to

befriend.

The tenderness and thoughtfulness of his disposition

are well shown in

[pg. 649]

the following incident: Upon one occasion, his son

received a kick from a horse, which he was about to

mount at the door. When he had recovered from the

shock, and it was found that he was not seriously

injured, the father still continued to look serious, and

did not cease to shed tears. On being asked why he

grieved, his answer was: "I was just thinking how

it would have been with thee, had that stroke proved

fatal." Such thoughts were at once the notes of

his own preparation and a warning to others to be also

ready.

A life consistent with his views, was a life of

humility and universal benevolence, and such was his.

It was a life, as it were in Heaven, while yet on earth,

for it soared above and beyond the corrupt and slavish

influences of earthly passions.

His interest in temperance never failed him. On

his death-bed ho would call persons to him, who needed

such advice, and admonish them on the subject of using

strong drinks, and his last expression of interest in

any humanitarian movement, was an avowal of his belief

in the great good to arise from a prohibitory liquor

law.

To a friend, who entered his sick room, a few days

before his death, he said: " Well, E., thee is

preparing to go to the West." The friend replied:

"Yes, and Daniel, I suppose thee is preparing to

go to eternity." There was an affirmative reply,

and E. inquired, "How does thee find it?"

Daniel said: "I don't find much to do, I

find that I have not got a hard master to deal with.

Some few things which I have done, I find not entirely

right." He quitted the earthly service of the

Master, on the 17th day of the eighth month, 1852.

A young physician, son of one of his old friends, after

attending his funeral, wrote to a friend, as follows:

"To quote the words of Webster, ' We turned and paused,

and joined our voices with the voices of the air, and

bade him hail ! and farewell!' Farewell, kind and

brave old man! The voices of the oppressed whom

thou hast redeemed, welcome thee to the Eternal City."

-------------------------

LUCRETIA MOTT.

Of all the women who served the Anti-slavery cause in

its darkest days, there is not one whose labors were

more effective, whose character is nobler, and who is

more universally respected and beloved, than Lucretia

Mott. You cannot speak of the slave

without remembering her, who did so much to make Slavery

impossible. You cannot speak of freedom, without

recalling that enfranchised spirit, which, free from all

control, save that of conscience and God, labored for

absolute liberty for the whole human race. We

cannot think of the partial triumph of freedom in this

country, without rejoicing in the great part she took in

the victory. Lucretia Mott is one of

[pg. 650]

the noblest representatives of ideal womanhood.

Those who know her, need not be told this, but those who

only love her in the spirit, may be sure that they can

have no faith too great in the beauty of her pure and

Christian life.

The book would be incomplete without giving some

account, however brief, of Lucretia Mott's

character and labors in the great work to which her life

has been devoted. To wright it fully would require

a volume. She was born in 1793, in the island of

Nantucket, and is descended from Coffins and

Macys, on the father's side, and from the Folgers,

on the mother's side, and through them is related to

Dr. Benjamin Franklin. Her maiden name was

Lucretia Coffin.

During the absence of her father on a long voyage, her

mother was engaged in mercantile business, purchasing

goods in Boston, in exchange for oil and candles, the

staples of the island. Mrs. Mott

says in reference to this employment: "The

exercise of women's talent in this line, as well as the

general care which devolved upon them in the absence of

their husbands, tended to develop their intellectual

powers, and strengthened them mentally and physically."

The family removed to Boston in 1804. Her parents

belonged to the religious Society of Friends, and

carefully cultivated in their children, the

peculiarities as well as the principles of that sect.

To this early training, we may ascribe the rigid

adherence of Mrs. Mott, to the beautiful

but sober costume of the Society.

When in London, in 1840, she visited the Zoological

Gardens, and a gentleman of the party, pointing out the

splendid plumage of some tropical birds, remarked :

"You see, Mrs. Mott, our heavenly Father

believes in bright colors. How much it would take

from our pleasure, if all the birds were dressed in

drab." "Yes;" she replied, "but immortal beings do

not depend upon feathers for their attractions.

With the infinite variety of the human face and form, of

thought, feeling and affection, we do not need gorgeous

apparel to distinguish us. Moreover, if it is

fitting that woman should dress in every color of the

rainbow, why not man also? Clergymen, with

their black clothes and white cravats, are quite as

monotonous as the Quakers. "Whatever may be the

abstract merit of this argument, it is certain that the

simplicity of Lucretia Mott's nature, is

beautifully expressed by her habitual costume.

In giving the principal events of Lucretia

Mott's life, we prefer to use her own language

whenever possible. In memoranda furnished by her

to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, she

says: "My father had a desire to make his

daughters useful. At fourteen years of age, I was

placed, with a younger sister, at the Friends' Boarding

School, in Dutchess county, State of New York, and

continued there for more than two years, without

returning home. At fifteen, one of the teachers

leaving the school, I was chosen as au assist

[pg. 651]

ant in her place. Pleased with the promotion, I

strove hard to give satisfaction, and was gratified, on

leaving the school, to have an offer of a situation as

teacher if I was disposed to remain; and informed that

my services should entitle another sister to her

education, without charge. My father was at that

time, in successful business in Boston, but with his

views of the importance of training a woman to

usefulness, he and my mother gave their consent to

another year being devoted to that institution."

Here is another instance of the immeasurable value of

wise parental influence.

In 1809 Lucretia joined her family in

Philadelphia, whither they had removed. "At the

early age of eighteen," she says, " I married James

Mott, of New York—an attachment formed while at

the boarding-school." Mr. Mott entered

into business with her father. Then followed

commercial depressions, the war of 1812, the death of

her father, and the family became involved in

difficulties. Mrs. Mott was again

obliged to resume teaching. "These trials," she

says, " in early life, were not without their good

effect in disciplining the mind, and leading it to set a

just estimate on worldly pleasures."

To this early training, to the example of a noble

father and excellent mother, to the trials which came so

quickly in her life, the rapid development of Mrs.

Mott's intellect is no doubt greatly due.

Thus the foundation was laid, which has enabled her, for

more than fifty years, to be one of the great workers in

the cause of suffering humanity. These are golden

words which we quote from her own modest notes:

"I, however, always loved the good, in childhood desired

to do the right, and had no faith in the generally

received idea of human depravity." Yes, it was

because she believed in human virtue, that she was

enabled to accomplish such a wonderful work. She had the

inspiration of faith, and entered her life battle

against Slavery with a divine hope, and not with a

gloomy despair.

The next great step in Lucretia Mott's

career, was taken at the age of twenty-five, when,

"summoned by a little family and many cares, I felt

called to a more public life of devotion to duty, and

engaged in the ministry in our Society."

In 1827 when the Society was divided Mrs.

Mott's convictions led her "to adhere to the

sufficiency of the light within us, resting on the truth

as authority, rather than 'taking authority for truth.'"

We may find no better place than this to refer to her

relations to Christianity. There are many people

who do not believe in the progress of religion.

They are right in one respect. God's truth cannot be

progressive because it is absolute, immutable and

eternal. But the human race is struggling up to a

higher comprehension of its own destiny and of the

mysterious purposes of God so far as they are revealed

to our finite intelligence. It is in this sense

that religion is progressive. The Christianity of

this age ought to be more intelligent than

[pg. 652]

the Christianity of Calvin. "The popular doctrine

of human depravity," says Mrs. Mott, "

never commended itself to my reason or conscience.

I searched the Scriptures daily, finding a construction

of the text wholly different from that which was pressed

upon our acceptance. The highest evidence of a

sound faith being the practical life of the Christian, I

have felt a far greater interest in the moral movements

of our age than in any theological discussion."

Her life is a noble evidence of the sincerity of this

belief. She has translated Christian principles

into daily deeds.

That spirit of benevolence which Mrs. Mott

possesses in a degree far above the average, of

necessity had countless modes of expression. She

was not so much a champion of any particular cause as of

all reforms. It was said of Charles Lamb

that he could not even hear the devil abused without

trying to say something in his favor, and with all

Mrs. Mott's intense hatred of Slavery we do

not think she ever had one unkind feeling toward the

slave holder. Her longest, and probably her

noblest work, was done in the antislavery cause.

"The millions of down-trodden slaves in our land," she

says, "being the greatest sufferers, the most oppressed

class, I have felt bound to plead their cause, in season

and out of season, to endeavor to put my soul in their

soul's stead, and to aid, all in my power, in every

right effort for their immediate emancipation."

When in 1833, Wm. Lloyd Garrison

took the ground of immediate emancipation and urged the

duty of unconditional liberty without expatriation,

Mrs. Mott took an active part in the

movement. She was one of the founders of the

Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society in 1834.

"Being actively associated in the efforts for the

slave's redemption," she says, "I have traveled

thousands of miles in this country, holding meetings in

some of the slave states, have been in the midst of mobs

and violence, and have shared abundantly in the odium

attached to the name of an uncompromising modern

abolitionist, as well as partaken richly of the sweet

return of peace attendant on those who would 'undo the

heavy burdens and let the oppressed go free, and break

every yoke."' In 1840 she attended the World's

Anti-Slavery Convention in London. Because she was

a woman she was not admitted as a delegate. All

the female delegates, however, were treated with

courtesy, though not with justice. Mrs.

Mott spoke frequently in the liberal churches of

England, and her influence outside of the Convention had

great effect on the Anti-Slavery movement in Great

Britain.

But the value of Mrs. Mott's anti-slavery

work is not limited to what she individually did, great

as that labor was. Her influence over others, and

especially the young, was extraordinary. She made

many converts, who went forth to spread the great ideas

of freedom throughout the land. No one can of

himself accomplish great good. He must labor

through others, he must inspire them, convince the

unbelieving, kindle the fires of faith in doubting

souls, and in the unequal fight of Right with Wrong make

Hope

[pg. 653]

take the place of despair. This Lucretia

Mott has done. Her example was an inspiration.

In the Temperance reform Mrs. Mott took

an early interest, and for many years she has practiced

total abstinence from intoxicating drinks In

the cause of Peace she has been ever active, believing

in the " ultra non-resistance ground, that no Christian

can consistently uphold and actively engage in and

support a government based on the sword." Yet

this, we believe, did not prevent her from taking a

profound interest in the great war for the Union; though

she deplored the means, her soul must have exulted in

the result. Through anguish and tears, blood and

death America wrought out her salvation. Do we not

believe that the United States leads the cause of human

freedom? It follows then that the abolition of the

gigantic system of human slavery in this country is the

grandest event in modern history. Mrs.

Mott has also been earnestly engaged in aid of the

working classes, and has labored effectively for " a

radical change in the system which makes the rich

richer, and the poor poorer." In the Woman's

Rights question she was early interested, and with

Mrs. Elizabeth Cady Stanton,

she organized, in 1848, a Woman's Rights' Convention at

Seneca Falls, New York. At the proceedings of this

meeting, "the nation was convulsed with laughter."

But who laughs now at this irresistible reform?

The public career of Lucretia Mott is in

perfect harmony with her private life. "My life in

the domestic sphere," she says, " has passed much as

that of other wives and mothers of this country. I

have had six children. Not accustomed to resigning

them to the care of a nurse, I was much confined to them

during their infancy and childhood.

"Notwithstanding her devotion to public matters her

private duties were never neglected. Many of our

readers will no doubt remember Mrs. Mott

at Anti-slavery meetings, her mind intently fixed upon

the proceedings, while her hands were as busily engaged

in useful sewing or knitting. It is not our place

to inquire too closely into this social circle, but we

may say that Mrs. Mott's history is a

living proof that the highest public duties may be

reconciled with perfect fidelity to private

responsibilities. It is so with men, why should it

be different with women?

In her marriage, Mrs. Mott was fortunate.

James Mott was a worthy partner for such a

woman. He was born in June, 1788, in Long Island.

He was an anti-slavery man, almost before such a thing

as anti-slavery was known. In 1812 he refused to

use any article which was produced by slave labor.

The directors of that greatest of all railway

corporations, the Underground Rail Road, will never

forget his services. He died, January 26, 1868,

having nearly completed his 80th year. "Not only

in regard to Slavery," said the "Philadelphia Morning

Post," at the time," but in all things was Mr.

Mott a reformer, and a radical, and while his

principles were absolute, and his opinions

uncompromising, his nature was singularly gener-

[pg. 654]

ous and humane. Charity was not to him a duty, but

a delight; and the benevolence, which, in most good men,

has some touch of vanity or selfish ness, always seemed

in him pure, unconscious and disinterested. His

life was long and happy, and useful to his fellow-men.

He had been married for fifty-seven years, and none of

the many friends of James and Lucretia

Mott, need be told how much that union meant, nor

what sorrow comes with its end in this world."

Mary Grew pronounced his fitting epitaph when

she said: "He was ever calm, steadfast, and strong in

the fore front of the conflict."

In her seventy-ninth year, the energy of Lucretia

Mott is undiminished, and her soul is as ardent

in the cause to which her life has been devoted, as when

in her youth she placed the will of a true woman against

the impotence of prejudiced millions. With the

abolition of Slavery, and the passage of the Fifteenth

Amendment, her greatest life-work ended. Since

then, she ha« given much of her time to the Female

Suffrage movement, and so late as November, 1871, she

took an active part in the Annual Meeting of the

Pennsylvania Peace Society.

Since the great law was enacted, which made all men,

black or white, equal in political rights—as they were

always equal in the sight of God— Mrs. Mott

has made it her business to visit every colored church

in Philadelphia. This we may regard as the formal

closing of fifty years of work in behalf of a race which

she has seen raised from a position of abject servitude,

to one higher than that of a monarch's throne. But

though she may have ended this Anti-slavery work, which

is but the foundation of the destiny of the colored race

in America, her influence is not ended—that cannot die;

it must live and grow and deepen, and generations hence

the world will be happier and better that Lucretia

Mott lived and labored for the good of all

mankind.

<

CLICK HERE to go

BACK to PAGES 623-641 > <

CLICK HERE to GO to

PAGES 654 to 679 >..

|