|

HISTORY of the FIFTY-FOURTH REGIMENT

of

MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY

1863-1865

by Luis Fenollosa Emilio

Published:

Boston:

The History Book Company

1894.

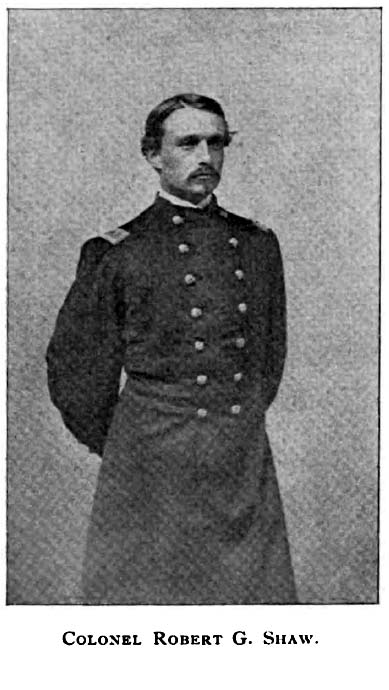

Colonel Robert G. Shaw.

FIFTY-FOURTH

MASSACHUSETTS INFANTRY.

----------

CHAPTER I.

RECRUITING

AT the close of the

year 1862, the military situation was discouraging to the

supporters of the Federal Government. We had been

repulsed at Fredericksburg and at Vicksburg, and at

tremendous cost had fought the battle of Stone River.

Some sixty-five thousand troops would be discharged during

the ensuing summer and fall. Volunteering was at a

standstill. On the other hand, the Confederates,

having filled their ranks, were never better fitted for

conflict. Politically, the opposition had grown

formidable, while the so-called "peace-faction" was strong,

and active for mediation.

IN consequence of the situation, the arming of negroes,

first determined upon in October, 1862, was fully adopted as

a military measure; and President Lincoln, on Jan. 1,

1863, issued the Emancipation Proclamation. In

September, 1862, General Butler began organizing the

Louisiana Native Guards from free negroes. General

Saxton, in the Department of the South, formed the First

South Carolina from contrabands in October of the same year.

Col. James Williams, in the summer of 1862,

[Pg. 2]

recruited the First Kansas Colored. After these

regiments next came, in order of organization, the

Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, which was the first raised in

the Northern States east of the Mississippi River.

Thenceforward the recruiting of colored troops, North and

South, was rapidly pushed. As a result of the measure,

167 organizations of all arms, embracing 186,097 enlisted

men of African descent, were mustered into the United States

service.

John A. Andrew, the war Governor of

Massachusetts, very early advocated the enlistment of

colored men to aid in suppressing the Rebellion. The

General Government having at last adopted this policy, he

visited Washington in January, 1863, and as a result of a

conference with Secretary Stanton, received the

following order, under which the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts

Volunteer Infantry was organized: --

| |

EDWIN M. STANTON,

Secretary of War. |

|

With this document the Governor at once returned to

Boston, anxious to begin recruiting under it before

the |

[Page 3]

| Government could

reconsider the matter. One of his first steps

was to transmit the following letter, outlining his

plans: -- |

| |

|

BOSTON, Jan. 30,

1863. |

FRANCIS G. SHAW, ESQ.,

Staten Island, N. Y.

DEAR SIR, - As you may have seen by the newspapers, I

am about to raise a colored regiment in

Massachusetts. This I cannot be regard as

perhaps the most important corps to be organized

during the whole war, in view of what must be the

composition of our new levies; and therefore I am

very anxious to organize it judiciously, in order

that it may be a model for all future colored

regiments. I am desirous to have for its

officers - particularly for its field-officers -

young men of military experience, of firm

antislavery principles, ambitious, superior to a

vulgar contempt for color, and having faith in the

capacity of colored men for military service.

Such officers must necessarily be gentlemen of the

highest tone and honor; and I shall look for them in

those circles of educated antislavery society which,

next to the colored race itself, have the greatest

interest in this experiment.

Reviewing the young men of the character I have

described, now in the Massachusetts service, it

occurs to me to offer the colonelcy to your son,

Captain Shaw, of the Second Massachusetts

Infantry, and the lieutenant-colonelcy to Captain

Hallowell of the Twentieth Massachusetts

Infantry, the son of Mr. Morris L. Hallowell

of Philadelphia. With my deep conviction of

the importance of this undertaking, in view of the

fact that it will be the first colored regiment to

be raised in the free States, and that its success

or its failure will go far to elevate or depress the

estimation in which the character of the colored

Americans will be held throughout the world, the

command of such a regiment seems to me to be a high

object of ambition for any officer. How much

your son may have reflected upon such a subject I do

not know, nor have I any information of his

disposition for such a task except what I |

[Page 4]

have derived from his general

character and reputation; nor should I wish him to

undertake it unless he could enter upon it with a

full sense of its importance, with an earnest

determination for its success, and with the assent

and sympathy and support of the opinions of his

immediate family.

I therefore enclose you the letter in which I make him

the offer of this commission; and I will be obliged

to you if you will forward it to him, accompanying

it with any expression to him of your own views, and

if you will also write to me upon the subject.

My mind is drawn towards Captain Shaw by many

considerations. I am sure he would attract the

support, sympathy, and active co-operation of many

among his immediate family relatives. The more

ardent, faithful, and true Republicans and friends

of liberty would recognize in him a scion from a

tree whose fruit and leaves have always contributed

to the strength and healing of our generation.

So it is with Captain Hallowell. His

father is a Quaker gentleman of Philadelphia, two of

whose sons are officers in our army, and another is

a merchant in Boston. Their house in

Philadelphia is a hospital and home for Massachusett

officers; and the family are full of good works; and

he was the adviser and confidant of our soldiery

when sick or on duty in that city. I need not

add that young Captain Hallowell is a gallant

and fine fellow, true as steel to the cause of

humanity, as well as to the flag of the country.

I wish to engage the field-officers, and then get their

aid in selecting those of the line. I have

offers from Oliver T. Beard of Brooklyn, N.

Y., late Lieutenant-Colonel of the Forty-eighth New

York Volunteers, who says he can already furnish six

hundred men; and from others wishing to furnish men

from New York and from Connecticut; but I do not

wish to start the regiment under a stranger to

Massachusetts. If in any way, by suggestion or

otherwise, you can aid the purpose which is the

burden of this letter, I shall receive your

co-operation with the heartiest gratitude. |

[Page 5]

|

I do not wish the office to go begging; and if the

offer is refused, I would prefer it being kept

reasonably private. Hoping to hear from you

immediately on receiving this letter, I am, with

high regard, |

| |

Your obedient servant and friend,

JOHN A. ANDREW |

Francis G. Shaw

himself took the formal proffer to his son, then in

Virginia. After due deliberation, Captain Shaw,

on February 6, telegraphed his acceptance.

Robert Gould Shaw was the grandson of Robert

G. Shaw of Boston. His father, prominently

identified with the Abolitionists, died in 1882, mourned as

one of the best and noblest of men. His mother,

Sarah Blake Sturgis, imparted to her only son the rare

and high traits of mind and heart she possessed.

He was born Oct. 10, 1837, in Boston, was carefully

educated at home and abroad in his earlier years, and

admitted to Harvard College in August, 1856, but

discontinued his course there in his third year. After

a short business career, on Apr. 19, 1861, he marched with

his regiment, the Seventh New York National Guard, to the

relief of Washington. He applied for and received a

commission as second lieutenant in the Second Massachusetts

Infantry; and after serving with his company and on the

staff of Gen. George H. Gordon, he was promoted to

captaincy. Colonel Shaw was of medium height,

with light hair and fair complexion, of pleasing aspect and

composed in his manners. His bearing was graceful, as

became a soldier and gentleman. His family connections

were of the highest social standing, character, and

influence. He married Miss Haggerty, of New

York City, on May 2, 1863.

[Page 6]

Captain Shaw arrived in Boston on February 15,

and at once assumed the duties of his position.

Captain Hallowell was already there, daily engaged in

the executive business of the new organization; and about

the middle of February, his brother, Edward N. Hallowell,

who had served as a lieutenant in the Twentieth

Massachusetts Infantry, also reported for duty, and was made

major of the Fifty-fourth before its departure for the

field.

Line-officers were commissioned from persons nominated

by commanders of regiments in the field, by tried friends of

the movement, the field-officers, and those Governor

Andrew personally desired to appoint. This freedom

of selection, - unhampered by claims arising from recruits

furnished or preferences of the enlisted men, so powerful in

officering white regiments, - secured for this organization

a corps of officers who brought exceptional character,

experience, and ardor to their allotted work. Of the

twenty-nine who took the field, fourteen were veteran

soldiers from three-yeas regiments, nine from nine-months

regiments, and one from the militia; six had previously been

commissioned. They included representatives of

well-known families; several were Harvard men; and some,

descendants of officers of the Revolution and the War of

1812. Their average age was about twenty-three years.

At the time a strong prejudice existed against arming

the blacks and those who dared to command them. The

sentiment of the country and of the army was opposed to the

measure. It was asserted that they would not fight,

that their employment would prolong the war, and that white

troops would refuse to serve with them. Besides the

moral courage required to accept commissions in the

Fifty-fourth at the time it was organizing, physical cour-

[Page 7]

age was also necessary, for the Confederate Congress, on May

1, 1863, passed an act, a portion of which read as follows:

-

"SECTION IV.

That every white person being a commissioned officer, or

acting as such, who, during the present war, shall command

negroes or mulattoes in arms against the Confederate Sates,

or who shall arm, train, organize, or prepare negroes or

mulattoes for military service against the Confederate

States, or who shall voluntarily aid negroes or mulattoes in

any military enterprise, attack, or conflict in such

service, shall be deemed as inciting servile insurrection,

and shall, if captured, be put to death or be otherwise

punished at the discretion of the Court."

The motives which

influenced many of those appointed are forcibly set forth in

the following extracts from a letter of William H.

Simpkins, then of the Forty-fourth Massachusetts

Infantry, who was killed in action when a captain in the

Fifty-fourth: -

"I have to tell you

of pretty important step that I have just taken. I

have given my name to be forwarded to Massachusetts for a

commission in the Fifth-fourth Negro Regiment, Colonel

Shaw. This is no hasty conclusion, no blind leap

of an enthusiast, but the result of much hard thinking.

It will not be at first, and probably not for a long time,

an agreeable position, for many reasons to evident to state

. . . . Then this is nothing but an experiment after all;

but it is an experiment that I think it high time we should

try, - an experiment which, the sooner we prove fortunate

the sooner we can count upon an immense number of hardy

troops that can stand the effect of a Southern climate

without injury; an experiment which the sooner we prove

unsuccessful, the sooner we shall establish an important

truth and rid ourselves of a false hope."

[Page 8]

From first to last the original officers exercised a

controlling influence in the regiment. To them -

field, staff, and line - was largely due whatever fame was

gained by the Fifty-fourth as a result of efficient

leadership in camp or on the battlefield.

In his "Memoirs of Governor Andrew" the Hon.

Peleg W. Chandler writes: -

"When the first

colored regiment was formed, the [Governor Andrew]

remarked to a friend that in regard to other regiments, he

accepted men as officers who were sometimes rough and

uncultivated, 'but these men,' he said, 'shall be commanded

by officers who are eminently gentlemen.'"

So much for the

selection of officers. When it came to filling the

ranks, strenuous efforts were required outside the State, as

the colored population could not furnish the number required

even for one regiment.

Pending the effort in the wider field available under

the plan proposed, steps were taken to begin recruiting with

the State. John W. M. Appleton, of Boston, a

gentleman of great energy and sanguine temperament, was the

first person selected for a commission in the Fifty-fourth,

which bore date of February 7. He reported to the

Governor, and received orders to begin recruiting. An

office was taken in Cambridge Street, corner of North

Russell, upstairs, in a building now torn down. On

February 16, the following call was published in the columns

of the "Boston Journal": -

TO COLORED MEN.

Wanted.

Good men for the Fifth-fourth Regiment of Massachusetts

Volunteers of African descent, Col. Robert G. Shaw.

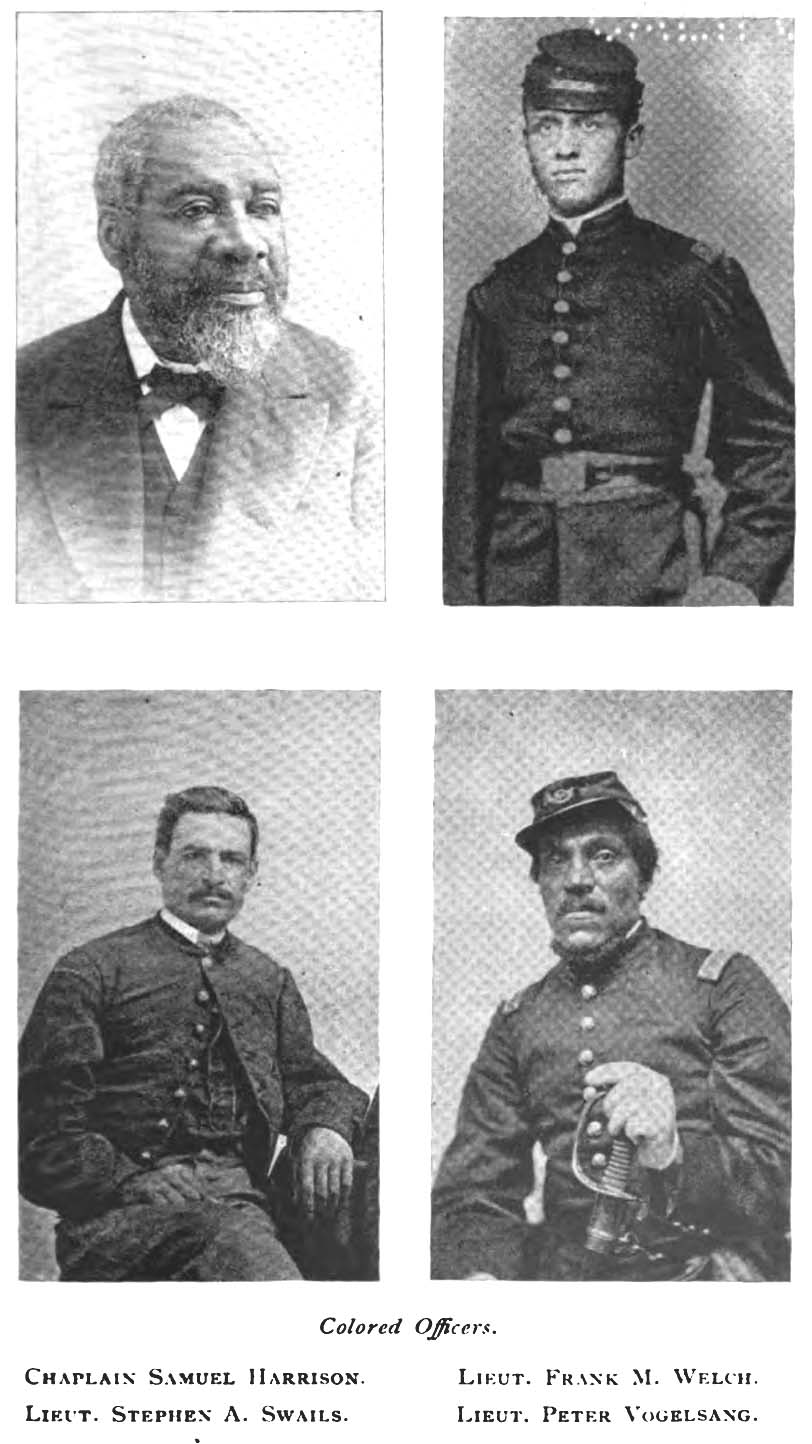

Chaplain Samuel Harrison

Lieut. Frank M. Welch

Lieut. Stephen A. Swails

Lieut. Peter Vogelsang

[Page 9]

$100 bounty at expiration of term of service. Pay $13

per month, and State aid for families. All necesary

information can be obtained at the office, corner Cambridge

and North Russell Streets.

LIEUT. J. W. M. APPLETON

Recruiting Officer.

In five days

twenty-five men were secured; and Lieutenant Appleton's

work was vigorous prosecuted, with measurable success.

It was not always an agreeable task, for the rougher element

was troublesome and insulting. About fifty or sixty

men were recruited at this office, which was closed about

the last of March. Lieutenant Appleton then

reported to the camp established and took command of Company

A, made up of his recruits and others afterward obtained.

Early in February quite a number of colored men were

recruited in Philadelphia, by Lieut. E. N. Hallowell,

James M. Walton, who was subsequently commissioned in

the Fifty-fourth, and Robert R. Corson, the

Massachusetts State Agent. Recruiting there was

attended with much annoyance. The gathering -place had

to be kept secret, and the men sent to Massachusetts in

small parties to avoid molestation or excitement.

Mr. Corson was obliged to purchase railroad tickets

himself, and get the recruits one at a time on the cars or

under cover of darkness. The men sent and brought from

Philadelphia went to form the major part of Company B.

New Bedford was also chosen as a fertile field.

James W. Grace, a young business man of that place,

was selected as recruiting officer, and commissioned

February 10. He opened headquarters on Williams

Street, near the postoffice and put out the United States

flag across the street.

[Page 10]

Colored ministers of the city were informed of his plans;

and Lieutenant Grace visited their churches to

interest the people in his work. He arranged for

William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Frederick

Douglass, and other noted men to address meetings.

Cornelius Howland, C. B. H. Fessenden, and James

B. Congdon materially assisted and were good friends of

the movement. While recruiting, Lieutenant Grace

was often insulted by such remarks as, "There goes the

captain of the Negro Company! He thinks the negroes

will fight! They will turn and run at the first sight

of the enemy!" His little son was scoffed at in school

because his father was raising a negro company to fight the

white men. Previous to departure, the New Bedford

recruits and their friends gathered for a farewell meeting.

William Berry presided; prayer was offered by Rev.

Mr. Grimes; and remarks were made by

Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell, Lieutenant Grae, C. B. H.

Fessenden, Ezra Wilson, Rev. Mr. Kelly, Wesley Furlong,

and Dr. Bayne. A collation at A. Taylor

and Company's followed. Temporarily the recruits took

the name of "Morgan Guards," in recognition of

kindnesses from S. Griffiths Morgan. At camp

the New Bedford men, - some seventy-five in number, - with

others from that place and elsewhere, became Company C, the

representative Massachusetts company.

Only one other commissioned officer is known to the

writer as having performed effective recruiting service.

This is Watson W. Bridge, who had been first

sergeant, Company D, Thirty-seventh Massachusetts Infantry.

His headquarters were at Springfield, and he worked n

Western Massachusetts and Connecticut. When ordered to

camp, about April 1, he had recruited some seventy men.

[Page 11]

Much the larger number of recruits were obtained

through the organization and by the means which will now be

described. About February 15, Governor Andrew

appointed a committee to superintend the raising of recruits

for the colored regiments, consisting of George L.

Stearns, Amos A. Lawrence, John M. Forbes, William I.

Bowditch, Le Baron Russell, and Richard P. Hallowell,

of Boston; Mayor Howland and James B. Congdon

of New Bedford; Willard P. Phillips, of Salem; and

Francis G. Shaw of New York. Subsequently the

membership was increased to one hundred, and it became known

as the "Black Committee." It was mainly instrumental

in procuring the men of the Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth

Massachusetts Infantry, the Fifth Massachusetts Cavalry,

besides 3,967 other colored men credited to the State.

All the gentlemen named were persons of prominence.

Most of them had been for years in the van of those advanced

thinkers and workers who had striven to help and free the

slave wherever found.

The first work of this committee was to collect money;

and in a very short time five thousand dollars was received,

Gerrit Smith, of New York, sending his check for five

hundred dollars. Altogether nearly one hundred

thousand dollars was collected, which passed through the

hands of Richard P. Hallowell, the treasurer, who was

a brother of the Hallowells commissioned in the

Fifth-fourth. A call for recruits was published in a

hundred journals from east to west. Friends whose

views were known were communicated with, and their aid

solicited; but the response was not for a time encouraging.

With the need came the man. Excepting Governor

Andrew, the highest praise for recruiting the

Fifty-fourth

[Page 12]

belongs to George L. Stearns, who had been closely

identified with the struggle in Kansas and John Brown's

projects. He was appointed agent for the committee,

and about February 23 went west on his mission. Mr.

Stearns stopped at Rochester, N. Y., to ask the aid of

Fred Douglass, received hearty co-operation, and

enrolling a son of Douglass as his first recruit.

His headquarters were made at Buffalo, and a line of

recruiting posts from Boston to St. Louis established.

Soon such success was met with in the work that after

filling the Fifty-fourth the number of recruits was

sufficient to warrant forming a sister regiment. Many

newspapers gave publicity to the efforts of Governor

Andew and the committee. Among the persons who

aided the project by speeches or as agents were George E.

Stephens, Daniel Calley, A. M. Green, Charles L. Remond,

William Wells Brown, Martin R. Delany, Stephen Myers, O. S.

B. Wall, Rev. William Jackson, John S. Rock, Rev. J. B.

Smith, Rev. H. Garnett, George T. Downing and Rev. J.

W. Loqueer.

Recruiting stations are

established, and meetings held at Nantucket, Fall River,

Newport, Providence, Pittsfield, New York City,

Philadelphia, Elmira, and other places throughout the

country. In response the most respectable,

intelligent, and courageous of the colored population

everywhere gave up their avocations, headed the enlistment

rolls, and persuaded others to join them.

Most memorable of all the meetings held in aid of

recruiting the Fifty-fourth was that at the Joy Street

Church, Boston, on the evening of February 16, which was

enthusiastic and largely attended. Robert Johnson,

Jr., presided; J. R. Sterling was the

Vice-President, and Fran-

[Page 13]

cis Fletcher Secretary. In opening, Mr.

Johnsonstated the object of the gathering. HE

thought that another year would show the importance of

having the black man in arms, and pleaded with his hearers,

by the love they bore their country, not to deter by word or

deed any person from entering the serving. Judge

Russell said in his remarks, "You want to be

line-officers yourselves." He thought they had a right

to be, and said, -

"If you want

commissions, go, earn, and get them. [Cheers.] Never

let it be said that when the country called, this reason

kept back a single man, but go cheerfully."

Edward L. Pierce

was the next speaker; and he reminded them of the many

equalities they had in common with the whites. He

called on them to stand by those who for half a century ahd

maintained that they would prove brave and noble and

patriotic when the opportunity came. Amid great

applause Wendell Phillips was introduced. The

last time he had met such an audience was when he was driven

from Tremont Temple by a mob. Since then the feeling

toward them had much changed. Some of the men who had

pursued and hunted him and them even to that very spot had

given up their lives on the battlefields of Virginia.

He said: -

"Now they offer you

a musket and say, 'Come and help us.' The question is,

will you of Massachusetts take hold? I hear there is

some reluctance because you are not to have officers of your

own color. This may be wrong, for I think you have as

much right to the first commission in a brigade as a white

man. No regiment should be without a mixture of the

races. But if you cannot have a whole loaf, will you

not take a slice?

[Page 14]

He recited reasons why it would be better to have white

officers, stating among other things that they would be more

likely to have justice done them and the prejudice more

surely overcome than if commanded by men of their own race.

He continued: -

"Your success hangs

on the general success. If the Union lives, it will

live with equal races. If divided, and you have done

your duty, then you will stand upon the same platform with

the white race. (Cheers.] Then make use of the offers

Government has made you; for if you are not willing to fight

your way up to office, you are not worthy of it. Put

yourselves under the stars and stripes, and fight yourselves

to the marquee of a general, and you shall come out with a

sword. [Cheers.]

Addresses were then

made by Lieutenant Colonel Hallowell, Robert C.

Morris, and others. It was a great meeting for the

colored people, and did much to aid recruiting.

Stirring appeals and addresses were written by J. M.

Langston, Elizur Wright, and others. One published

by Frederick Douglass in his own paper, at Rochester,

N. Y., was the most eloquent in inspiring. The

following is extracted: -

"We can get at the

throat of treason and slavery through the State of

Massachusetts. She was first in the War of

Independence; first to break the chains of her slaves; first

to make the black man equal before the law; first to admit

colored children to her common schools. She was first

to answer with her blood the alarm-cry of the nation when

its capital was menaced by the Rebels. You know her

patriotic Governor, and you know Charles Sumner.

I need add no more. Massachusetts now welcomes you as

her soldiers." . . .

[Page 15]

In consequence of the cold weather there was some

suffering in the regimental camp. When this became

known, a meeting was held at a private residence on March

10, and a committee of six ladies and four gentlemen was

appointed to procure comforts, necessities and a flag.

Colonel Shaw was present, and gave an account of

progress. To provide a fund, a levee was held at

Chickering Hall on the evening of March 20, when speeches

were made by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Wendell Phillips, Rev.

Dr. Neale, Rev. Father Taylor, Judge Russell, and

Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell. Later, through the

efforts of Colonel Shaw and Lieutenant-Colonel

Hallowell, a special fund of five hundred dollars was

contributed to purchase musical instruments and to instruct

and equip a band.

Besides subscriptions, certain sums of money were

received from towns and cities of the State, for volunteers

in the Fifty-fourth credited to their quota. The

members of the committee contributed liberally to the funds

required, and the following is a partial list of those who

aided the organization in various ways: -

George Putnam,

Charles G. Loring,

J. Huntington Wolcott,

Samuel G. Ward,

James M. Barnard,

William F. Weld,

J. Wiley Edmands,

William Endicott, Jr.,

Francis L. Lee,

Oakes Ames,

James L. Little,

Marshall S. Scudder |

George Higginson,

Thomas Russell,

Edward S. Philbrick,

Oliver Ellsworth,

Robert W. Hooper,

John H. Stevenson,

John H. Silsbee,

Manuel Fenollosa,

G. Mitchell,

John W. Brooks,

Samuel Cabot, Jr.,

John Lowell, |

[Page 16]

James T. Fields,

Henry Lee, Jr.,

George S. Hale,

William Dwight,

Richard P. Waters,

Avery Plummer, Jr.,

Alexander H. Rice,

John J. May,

John Gardner,

Mrs. Chas. W. Sumner,

Albert G. Browne,

Ralph Waldo Emerson,

William B. Rogers,

Charles Buffum,

John S. Emery,

Gerritt Smith,

Albert G. Browne, Jr.,

Mrs. S. R. Urbino,

Edward W. Kinsley,

Uriah and John Ritchie,

Pond & Duncklee,

John H. and Mary E. Cabot,

Mary P. Payson,

Manuel Emilio,

Henry W. Holland, |

Miss Halliburton,

Frederick Tudor,

Samuel Johnson,

Mary E. Stearns,

Mrs. William J. Loring,

Mrs. Governor Andrew,

Mrs. Robert C. Waterton,

Wright & Potter,

James B. Dow,

William Cumston,

John A. Higginson,

Peter Smith,

Theodore Otis,

Avery Plummer,

James Savage,

Samuel May,

Mrs. Samuel May,

Josiah Quincy,

William Claflin,

Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis,

George Bemis,

Edward Atkinson,

Professor Agassiz,

John G. Palfrey, |

besides several societies and fraternities.

Most of the papers connected with the labors of the

committee were destroyed in the great Boston fire, so that

it is difficult now to set forth properly in greater detail

the work accomplished.

In the proclamation

of outlawry issued by Jefferson Davis, Dec.

23, 1862, against Major-General Butler, was the

following clause: -

[Page 17]

"Third. That

all negro slaves captured in arms be at once delivered over

to the executive authorities of the respective States to

which they belong, to be dealt with according to the laws of

said States.

The act passed by

the Confederate Congress previously referred to, contained a

section which extended the same penalty to negroes or

mulattoes captured, or who gave aid or comfort to the

enemies of the Confederacy. Those who enlisted in the

Fifty-fourth did so under these acts of outlawry bearing the

penalties provided. Aware of these facts, confident in

the protection the Government would and should afford, but

desirous of having official assurances, George T. Downing

wrote regarding the status of the Fifty-fourth men, and

received the following reply: -

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS, EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT,

BOSTON, March 23, 1863.

GEORGE T. DOWNING, ESQ., New York.

DEAR SIR, - In reply to your inquiries made as to

the position of colored men who may be enlisted into the

volunteer service of the United States, I would say that

their position in respect to pay, equipments, bounty, or any

aid or protection when so mustered is that of any and all

other volunteers.

I desire further to state to you that when I was in

Washington on one occasion, in an interview with Mr.

Stanton, the Secretary of War, he stated in the most

emphatic manner that he would never consent that free

colored men should be accepted into the service to serve as

soldiers in the South, until he should be assured that the

Government of the United States was prepared to guarantee

and defend to the last dollar and the last man, to these

men, all the rights, privileges, and immunities that are

given by the laws of civilized warfare to other soldiers.

Their present acceptance and muster-in as soldiers

[Page 18]

pledges the honor of the nation in the same degree and to

the same rights with all. They will be soldiers of the

Union, nothing less and nothing different. I believe

they will earn for themselves an honorable fame, vindicating

their race and redressing their future from the aspersions

of the past.

I am, yours truly,

JOHN ANDREW.

Having recited the

measures and means whereby the Fifty-fourth was organized,

the history proper of the regiment will now be entered upon.

< CLICK HERE

to RETURN to TABLE of CONTENTS >

|