|

HISTORY of the FIFTY-FOURTH REGIMENT

of

MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY

1863-1865

by Luis Fenollosa Emilio

Published:

Boston:

The History Book Company

1894.

----------

CHAPTER IV.

DESCENT ON JAMES ISLAND

[Page 51]

ALL

suspense regarding the employment of the Fifty-fourth ended July 8,

with the receipt, about noon, of orders to move at an hour's notice,

taking only blankets and rations. Three hours after, the

regiment began to embark, headquarters with seven companies finding

transportation on the steamer "Chasseur," the remaining ones on the

steamer "Cossack," with Colonel Montgomery and staff.

Lieutenant Littlefield, with a guard of one

hundred men, was detailed to remain at St. Helena in charge of the

camp. Assistant-Surgeon Bridgham also remained with the

sick. Captain Bridge and Lieutenant Walton were

unable to go on account of illness. A start was made late in

the afternoon in a thunder-storm, the "Cossack" stopping at Hilton

Head to take on Captain Emilio and a detail of ninety

men there. The following night was made miserable by wet

clothes, a scarcity of water, and the crowded condition of the small

steamers.

About 1 a. m. on the 9th, the transports arrived off

Stono Inlet; the bar was crossed at noon; and anchors were cast off

Folly Island. The inlet was full of transports, loaded with

troops, gunboats, and supply vessels, betokening an important

movement made openly.

General Gillmore's plans should be

briefly stated. He desired to gain possession of Morris

Island, then in the

[Page 52]

enemy's hands, and fortified. He had at disposal ten

thousand infantry, three hundred and fifty artillerists, and

six hundred engineers; thirty-six pieces of field artillery,

thirty Parrott guns, twenty-seven siege' and three Cohorn

mortars, besides ample tools and 'material. Admiral

Dahlgren was to co-operate. On Folly Island, in

our possession, batteries were constructed near Lighthouse

Inlet, opposite Morris Island, concealed by the sand

hillocks and undergrowth. Gillmore's real

attack was to be made from this point by a coup de main, the

infantry crossing the inlet in boats covered by a

bombardment from land and sea. Brig. Gen. Alfred

H. Terry, with four thousand men, was to make a

demonstration on James Island. Col. T. W. Higginson,

with part of his First South Carolina Colored and a section

of artillery, was to ascend the South Edisto River, and cut

the railroad at Jacksonboro. This latter force,

however, was repulsed with the loss of two guns and the

steamer "Governor Milton."

Late in the afternoon of the 9th Terry's division

moved. The monitor "Nantucket," gunboats "Pawnee" and "Commodore

McDonough," and mortar schooner" C. P. Williams

"passed up the river, firing on James Island to the right

and John's Island to the left, followed by thirteen

transports carrying troops. Col. W. W. H. Davis,

with portions of his regiment — the One Hundred and Fourth

Pennsylvania - and the Fifty-second Pennsylvania, landed on

Battery Island, advancing to a bridge leading to James

Island.

Heavy cannonading was heard in the direction of Morris

Island, at 6 a. m. on the 10th. Before night word came

that all the ground south of Fort Wagner on Morris Island

[Page 53]

was captured with many guns and prisoners. This news was

received with rousing cheers by Terry's men and the sailors.

At dawn Colonel Davis's men crossed to James Island,

his skirmishers driving a few cavalry. At an old house the

main force halted with pickets advanced. While this movement

was taking place, a portion of the other troops landed. That

day a mail brought news of Vicksburg's capture and Lee's defeat at

Gettysburg. Lieut. Edward B. Emerson joined the

Fifty-fourth from the North.

About noon of the 11th, the regiment landed, marched

about a mile, and camped in open ground on the furrows of an old

field. The woods near by furnished material for brush shelters

as a protection against the July sun. By that night all troops

were ashore. Terry's division consisted of three

brigades, — Davis's, of the Fifty-second and One Hundred and

Fourth Pennsylvania and Fifty-sixth New York; Brig. Gen. Thomas

G. Stevenson's, of the Twenty-fourth Massachusetts, Tenth

Connecticut, and Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania; and Montgomery's, of

the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts and Second South Carolina.

James Island is separated from the mainland by Wappoo

Creek. From the landing a road led onward, which soon

separated into two: one running to the right through timber, across

low sandy ground to Secessionville; the other to the left, over open

fields across the low ground, past Dr. Thomas Grimball's

house on to the Wappoo. The low ground crossed by both these

roads over cause ways formed the front of Terry's lines, and

was commanded by our naval vessels. Fort Pemberton, on the

Stono, constituted the enemy's right. Thence the line was

retired partially behind James Island Creek, con-

[Page 54]

sisting of detached light works for field-guns and infantry.

Their left was the fortified camp of Secessionville, where, before

Battery Lamar, General Benham was repulsed in

the spring of 1862.

General Beauregard, the Confederate

Department commander, considered an attack on Charleston by way of

James Island as the most dangerous to its safety. He posted

his forces accordingly, and on July 10 had 2,926 effectives there,

with 927 on Morris Island, 1,158 on Sullivan's Island, and 850 in

the city. Few troops from other points were spared when Morris

Island was attacked on the 10th; therefore Terry's diversion

had been effective. Had Beauregard's weakness been

known, Terry's demonstration in superior force might have

been converted into a real attack, and James Island fallen before

it, when Charleston must have surrendered or been destroyed.

Captain Willard, on the 11th, with

Company B, was sent to John's Island at Legareville to prevent a

repetition of firing upon our vessels by artillery such as had

occurred that morning.

In the afternoon the Tenth Connecticut and

Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania, covered by the "Pawnee's" fire,

advanced the picket line. Word was received of an unsuccessful

assault on Fort Wagner, with considerable loss to us.

Abraham F. Brown of Company E accidentally shot himself to death

with a small pistol he was cleaning. Late that afternoon

Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell, with Companies D, F, I, and K,

went out on picket in front of our right, remaining throughout a

dark and stormy night. During the night of the 13th,

Captain Emilio, with Company E, picketed about

Legareville. Capt A.

[Page 55]

P. Rockwell's First Connecticut Battery arrived from

Beaufort on the 14th.

Between the 10th and 16th there had arrived for the

enemy from Georgia and North Carolina two four-gun batteries

and six regiments of infantry. Beauregard also reduced

his force on Morris Island and concentrated on James,

under command of Brig. Gen. Johnson Hagood.

Gillmore still kept Terry there, inviting attack,

although the purpose of the diversion had been accomplished.

On the 15th the enemy demonstrated in front of the Tenth

Connecticut pickets. It was rumored that two scouts

had been seen about our lines.

Some thought had been given to securing a line of

retreat; for the engineers were reconstructing the broken

bridge leading from James Island, and repairing causeways,

dikes, and foot-bridges across the marshes along the old

road to Cole's Island, formerly used by the Confederates.

Companies B, H, and K, of the Fifty-fourth, under

command of Captain Willard, were detailed for

picket on the 15th, and about 6 p. m. relieved men of

Davis's brigade. Captain Russel and

Lieutenant Howard, with Company H, held the

right from near a creek, over rolling ground and rather open

country covered with high grass and thistles.

Captain Simpkins and Lieut. R. H. L. Jewett

held the left of the Fifty-fourth line with Company K and a

portion of Company B. It was over lower ground,

running obliquely through a growth of small timber and

brush. There was a broken bridge in the front. A

reserve, consisting of the remainder of Company B, under

Lieut. Thomas L. Appleton, was held at a stone house.

Captain Willard's force was five officers and

about two

[Page 56]

hundred men. From Simpkins's left to the Stono

the picket line was continued by men of the Tenth

Connecticut, holding a dangerous position, as it had a swamp

in rear. Frequent showers of rain fell that evening.

All night following, the enemy was uneasy. Lurking men

were seen, and occasional shots rang out. Captain

Willard, mounting the roof of the house, could see

great activity among the signal corps of the enemy. He

sent word to his officers to be vigilant, and prepared for

attack in the morning.

About midnight the men were placed in skirmishing

order, and so remained. Sergeant Stephens of

Company B relates that George Brown of his company, a

" dare-devil fellow," crawled out on his hands and knees and

fired at the enemy's pickets.

An attack was indeed impending, arranged on the

following plan: Brig. Gen. A. H. Colquitt, with the

Twenty-fifth South Carolina, Sixth and Nineteenth Georgia,

and four companies Thirty-second Georgia, about fourteen

hundred men, supported by the Marion Artillery, was to cross

the marsh at the causeway nearest Secessionville, "drive the

enemy as far as the lower causeway [nearest Stono] rapidly

recross the marsh at that point by a flank movement, and cut

off and capture the force encamped at Grimball's."

Col. C. H. Way, Fifty-fourth Georgia, with eight hundred

men, was to follow and co-operate. A reserve of one

company of cavalry, one of infantry, and a section of

artillery, was at Rivers's house. Two Napoleon guns

each, of the Chatham Artillery, and Blake's Battery,

and four twelve-pounders of the Siege Train, supported by

four hundred infantry, were to attack the gunboats "Pawnee"

and "Marblehead" in the Stono River.

[Page 57]

In the gray of early dawn

of July 16, the troops in bivouac on James Island were awakened by

dropping shots, and then heavy firing on the picket line to the

right. Clambering to the top of a pile of cracker-boxes, an

officer of the Fifty-fourth, looking in the direction of the firing,

saw the flashes of musketry along the out posts. In a few

moments came the sharp metallic explosions from field-guns to the

left by the river-bank. Wilkie James, the

adjutant, rode in post-haste along the line, with cheery voice but

unusually excited manner, ordering company commanders to form.

"Fall in! fall in!" resounded on all sides, while drums of the

several regiments were beating the long-roll. But a few

moments sufficed for the Fifty-fourth to form, when Colonel Shaw

marched it to the right and some little distance to the rear,

where it halted, faced to the front, and stood in line of battle at

right angles to the Secessionville road.

Rapid work was going on at the outposts. Before

dawn the pickets of the Fifty-fourth had heard hoarse commands and

the sound of marching men coming from the bank of darkness before

them. Soon a line of men in open order came sweeping toward

them from the gloom into the nearer and clearer light.

Colquitt, with six companies of the Eutaw

Regiment (Twenty-fifth South Carolina), skirmishing before his

infantry column, crossing Rivera's causeway, was rapidly advancing

on the black pickets.

Simpkins's right was the first point of contact;

and the men, thus suddenly attacked by a heavy force, discharged

their pieces, and sullenly contested the way, firing as they went,

over rough and difficult ground, which obstructed the enemy's

advance as well as their own retirement.

[Page 58]

Soon the enemy gained the

road at a point in rear of Russel's right. Some of the men

there, hardly aware of their extremity, were still holding their

positions against those of the enemy who appeared in the immediate

front. It seemed to Sergt. Peter Vogelsang

of Company H, who had his post at a palmetto-tree, that in a moment

one hundred Rebels were swarming about him. He led his

comrades to join men on his left, where they advanced, firing.

With effect too, for they came to the body of a dead Rebel, from

whom Vogelsang took a musket. Russel's right

posts, thus cut off, were followed by a company of the Nineteenth

Georgia, and after the desultory fighting were driven, to escape

capture, into the creek on the right of the line, where some were

drowned.

Those most courageous refused to fall back, and were

killed or taken as prisoners. Sergt. James D. Wilson of

Company H was one of the former. He was an expert in the use

of the musket, having been employed with the famous Ellsworth

Zouaves of Chicago. Many times he had declared to his

comrades that he would never retreat or surrender to the enemy.

On that morning, when attacked, he called to his men to stand fast.

Assailed by five men, he is said to have disabled three of them.

Some cavalrymen coming up, he charged them with a shout as they

circled about him, keeping them all at bay for a time with the

bayonet of his discharged musket, until the brave fellow sank in

death with three mortal besides other wounds.

Captain Russel, finding that the enemy

had turned his flank before he could face back, had to retire with

such men as were not cut off, at double-quick, finding the foe about

the reserve house when he reached it. A mounted

[Page 59]

officer charged up to Russel, and cut twice at his head with

his sword. Preston Williams of Company H caught

the second sweep upon his bayonet and shot the Confederate through

the neck, thus saving his captain's life. From the reserve

house Russel and his men retired, fighting as they could.

Captain Simpkins's right, as has been

told, first bore the force of the attack. By strenuous efforts

and great personal exposure that cool and gallant officer collected

some men in line. With them he contested the way back step by

step, halting now and then to face about and fire, thus gaining

time, the loss of which thwarted the enemy's plan. Of his men,

Corp. Henry A. Field of Company K especially distinguished

himself.

Captain Willard at the reserve house at

once sent back word, by a mounted orderly, of the situation.

To the support of his right he sent Lieutenant Appleton

with some men, and to the left First Sergeant Simmons of

Company B with a small force, and then looked for aid from our main

body. He endeavored to form a line of skirmishers, when the

men began coming back from the front, but with little success.

The men could not be kept in view because of the underbrush nearly

as high as a man. As the expected succor did not come, the

officers and the remaining men made their way back to the division.

It will be remembered that with the first musket-shots

came the sound of field-guns from the Stono. The enemy's four

Napoleons had galloped into battery within four hundred yards of the

gunboats, and fired some ten rounds before they were replied to;

their shots crashed through the "Pawnee" again and again, with some

loss. It was im-

[Page 60]

possible for the gunboats to turn in the narrow stream, and their

guns did not bear properly. To drop down was dangerous, but it was

done; when out of close range, the "Marblehead," "Pawnee," and

"Huron" soon drove their tormentors away from the river-bank.

To capture the Tenth Connecticut, the enemy, after

dealing with the Fifty-fourth, sent a portion of his force; but the

resistance made by Captain Simpkins had allowed time for the Tenth

Connecticut to abandon its dangerous position at the double-quick.

None too soon, however, for five minutes' delay would have been

fatal.

A correspondent of "The Reflector," writing from Morris

Island a few days later, said: -

"The boys of the Tenth

Connecticut could not help loving the men who saved them from

destruction. I have been deeply affected at hearing this feeling

expressed by officers and men of the Connecticut regiment; and

probably a thousand homes from Windham to Fairfield have in letters

been told the story how the dark-skinned heroes fought the good

fight and covered with their own brave hearts the retreat of

brothers, sons, and fathers of Connecticut."

The valuable time gained by

the resistance of the Fifty-fourth pickets had also permitted the

formation of Terry's division in line of battle. Hardly

had the Fifty-fourth taken its position before men from the front

came straggling in, all bearing evidence of struggles with bush and

brier, some of the wounded limping along unassisted, others helped

by comrades. One poor fellow, with his right arm shattered,

still carried his musket in his left hand.

Captain Russel appeared in sight,

assisting a sergeant

[Page 61]

badly wounded. Bringing up the rear came Captains

Willard and Simpkins, the latter with his trousers and

rubber coat pierced with bullets. As the pickets and

their officers reached the regiment, they took their places

in line.

A few minutes after these events, the enemy, having

advanced to a position within about six hundred yards of the

Federal line, opened fire with guns of the Marion Artillery,

making good line shots, but fortunately too high.

It was a supreme moment for the Fifty-fourth, then

under fire as a regiment for the first time. The sight

of wounded comrades had been a trial; and the screaming shot

and shell flying overhead, cutting the branches of trees to

the right, had a deadly sound. But the dark line stood

stanch, holding the front at the most vital point. Not

a man was out of place, as the officers could see while they

stood in rear of the lines, observing their men.

In reply to the enemy's guns the Connecticut battery

fired percussion-shells, and for some time this artillery

duel continued. To those who were anticipating an

attack by infantry, and looking for the support of the

gunboats, their silence was ominous. Every ear was

strained to catch the welcome sound, and at last it came in

great booms from Parrott guns. Very opportunely, too,

on the night before, the armed transports "John

Adams" and "Mayflower" had run up the creek on our right

flank, and their guns were fired twelve or fifteen times

with good effect before the enemy retired.

The expected attack on Terry's line by infantry

did not take place, for after about an hour the enemy

retired in some confusion. By General

Terry's order, the Fifty

[Page 62]

fourth was at once directed to reoccupy the old picket line.

Captain Jones with two companies advanced,

skirmishing; and the main body followed, encountering arms

and equipments of the enemy strewn over a broad trail.

At the reserve house the regiment halted in support of a

strong picket line thrown out. Parties were sent to

scour the ground, finding several wounded men lying in the

brush or in the marsh across the creek. They also

brought in the body of a Confederate, almost a child, with

soft skin and long fair hair, red with his own blood.

This youthful victim of the fight was tenderly buried soon

after.

Some of our dead at first appeared to be mutilated; but

closer inspection revealed the fact that the fiddler-crabs,

and not the enemy, did the work. It was told by some

of those who lay concealed, that where Confederate officers

were, the colored soldiers had been protected; but that in

other cases short shrift was given, and three men had been

shot and others bayonetted.

Colonel Shaw had despatched Adjutant

James to report that the old line was re-established.

He returned with the following message from General

Terry: "Tell your colonel that I am exceedingly

pleased with the conduct of your regiment. They have

done all they could do."

During the afternoon a mail was received. After

reading their letters Colonel Shaw and

Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell conversed. The

colonel asked the major if he believed in presentiments, and

added that he felt he would be killed in the first action.

Asked to try to shake off the feeling, he quietly said, "I

will try." General Beauregard reported his loss

as three killed,

[Page 63]

twelve wounded, and three missing, which is believed

to be an under-estimate. We found two dead Confederates,

and captured six prisoners representing four regiments.

The Adjutant-General of Massachusetts gives the Fifty-fourth

loss as fourteen killed, eighteen wounded, and thirteen missing. Outside our regiment the casualties were

very light.

General Terry in his official report says:

-

" I desire to express my

obligations to Captain Balch, United

States Navy, commanding the naval forces in the river, for the

very great assistance rendered to me, and to report to the commanding general the good services of

Captain Rockwell and

his battery, and the steadiness and soldierly conduct of the

Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment who were on duty at

the outposts on the right and met the brunt of attack."

General Terry was ordered

to evacuate James Island

that night. At about five o'clock p. m., the Fifty-fourth

was relieved by the Fifty-second Pennsylvania, and returned to the bivouac. While awaiting the marching

orders, several officers and men of the Tenth Connecticut

came to express their appreciation of the service rendered

by the Fifty-fourth companies attacked in the morning, by

which they were enabled to effect a safe retreat. Afterward, upon Morris Island the colonel of that regiment

made similar expressions.

Col. W. W. H. Davis, with his own and Montgomery's

brigades, and the Tenth Connecticut, was to retire by the

land route. Brigadier-General Stevenson's Twenty-fourth

Massachusetts and Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania were ordered to take transports from James Island.

By Colonel Davis's order the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts

[Page 64]

was given the advance, moving at 9.30 o'clock that night, followed

by the other regiments, the route being pointed out by guides from

the engineers, who accompanied the head of column.

All stores, ammunition, and horses of the Fifty-fourth

were put on board the steamer "Boston" by Quartermaster Ritchie,

who, with his men, worked all night in the mud and rain.

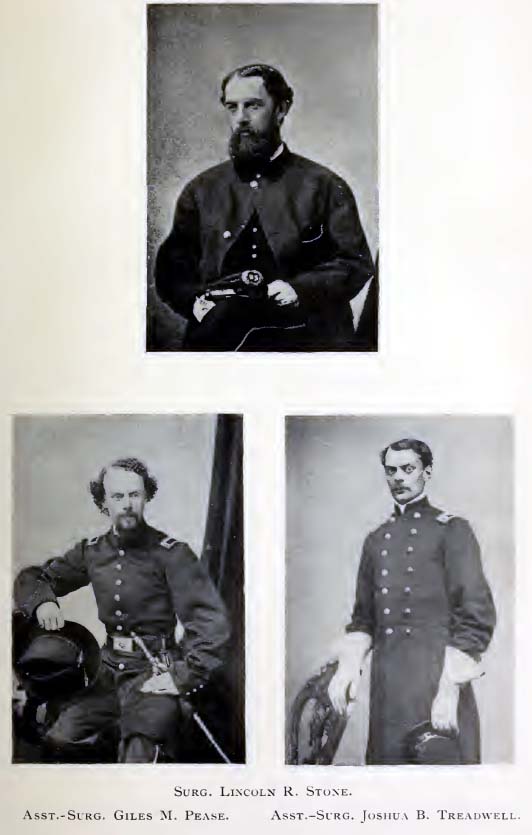

Surgeon Lincoln R. Stone of the Fifty-fourth and Surgeon

Samuel A. Green of the Twenty-fourth Massachusetts saw that all

the wounded were properly cared for, and also embarked.

It was a stormy night, with frequent flashes of

lightning, and pouring rain. Colonel Davis, at the

proper time, saw to the withdrawal of the Fifty-second Pennsylvania,

which held the front lines. So silently was the operation

accomplished that the enemy did not discover our evacuation until

daylight. When the Fifty-sixth New York, the rear-guard, had

crossed the bridge leading from James Island, at 1 a. m., on the

17th, it was effectually destroyed, thus rendering pursuit

difficult.

That night's march was a memorable one, for the

difficulties of the way were exceptional, and only to be encountered

upon the Sea Islands. After passing the bridge, the road led

along narrow causeways and paths only wide enough for two men to

pass abreast; over swamps, and streams bridged for long distances by

structures of frail piling, supporting one or two planks with no

hand-rail. A driving rain poured down nearly the whole time,

and the darkness was intense. Blinding flashes of lightning

momentarily illumined the way, then fading but to render the

blackness deeper.

Throughout most of the march the men were obliged to

[Page 65]

move in single file, groping their way and grasping their leader as

they progressed, that they might not separate or go astray.

Along the foot-bridges the planks became slippery with mire from

muddy feet, rendering the footing insecure, and occasioning frequent

falls, which delayed progress. Through the woods, wet branches

overhanging the path, displaced by the leaders, swept back with

bitter force into the faces of those following. Great clods of

clay gathered on the feet of the men.

Two hours were consumed in passing over the dikes and

foot-bridges alone. In distance the route was but a few miles, yet

it was daybreak when the leading companies reached firmer ground.

Then the men flung them selves on the wet ground, and in a moment

were in deep sleep, while the column closed up. Reunited solidly

again, the march was resumed, and Cole's Island soon reached. The

regiments following the Fifty-fourth had the benefit of daylight

most of the way.

Footsore, weary, hungry, and thirsty, the regiment was

halted near the beach opposite Folly Island about 5 a. m., on the

17th. Sleep was had until the burning sun awakened the greater

number. Regiments had been arriving and departing all the

morning. Rations were not procurable, and they were fortunate

who could find a few crumbs or morsels of meat in their haversacks.

Even water was hard to obtain, for crowds of soldiers collected

about the few sources of supply. By noon the heat and glare

from the white sand were almost intolerable.

In the evening a moist cool breeze came; and at eight

o'clock the regiment moved up the shore to a creek in readiness to

embark on the "General Hunter," lying in the stream. It was found

that the only means of board

[Page 66]

ing the steamer was by a leaky long-boat which would hold about

thirty men. Definite orders came to report the regiment to

General Strong at Morris Island without delay, and at 10

p. m. the embarkation began. By the light of a single lantern

the men were stowed in the boat.

Rain was pouring down in torrents, for a thunder storm

was raging. Throughout that interminable night the long-boat

was kept plying from shore to vessel and back, while those on land

stood or crouched about in dripping clothes, awaiting their turn for

ferriage to the steamer, whose dim light showed feebly in the gloom.

The boat journey was made with difficulty, for the current was

strong, and the crowded soldiers obstructed the rowers in their

task. It was an all night's work. Colonel Shaw

saw personally to the embarkation; and as daylight was breaking

he stepped in with the last boat-load, and himself guided the craft

to the "Hunter." Thus with rare self-sacrifice and fine

example, he shared the exposure of every man, when the comfortable

cabin of the steamer was at his disposal from the evening before.

|