|

HISTORY of the FIFTY-FOURTH

REGIMENT

of

MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY

1863-1865

by Luis Fenollosa Emilio

Published:

Boston:

The History Book Company

1894.

----------

CHAPTER V.

THE GREATER ASSAULT ON WAGNER

[Page 67]

ON the "General

Hunter" the officers procured breakfast; but the men were still

without rations. Refreshed, the officers were all together for

the last time socially; before another day three were dead, and

three wounded who never returned. Captain Simpkins,

whose manly appearance and clear-cut features were so pleasing to

look up, was, as always, quiet and dignified; Captain Russell

was voluble and active as ever, despite all fatigue. Neither

appeared to have any premonition of their fate. It was

different with Colonel Shaw, who again expressed to

Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell his apprehension of speedy death.

Running up Folly River, the steamer arrived at Pawnee

Landing, where, at 9 A.M., the Fifty-fourth disembarked.

Crossing the island through woods, the camps of several regiments

were passed, from which soldiers ran out, shouting, "Well done! we

heard your guns!" Others cried, "Hurrah, boys! you saved the

Tenth Connecticut!" Leaving the timber, the Fifty-fourth came

to the sea beach, where marching was easier. Stretching away

to the horizon, on the right, was the Atlantic; to the left, sand

hillocks, with pine woods farther inland. Occasional squalls

of rain came, bringing rubber blankets and coats into use. At

one point on the beach, a box of water-soaked hard bread was

discovered, and the contents speedily

[Page 68]

divided among the hungry men. Firing at the front had been

heard from early morning, which toward noon was observed to have

risen into a heavy cannonade.

After a march of some six miles, we arrived at

Lighthouse Inlet and rested, awaiting transportation. Tuneful

voices about the colors started the song, "When this Cruel War is

Over," and the pathetic words of the chorus were taken up by others.

It was the last song of many; but few then thought it was requiem.

By ascending the sand-hills, we could see the distant vessels

engaging Wagner. When all was prepared, the

Fifty-fourth boarded a smaller steamer, landed on Morris Island,

about 5 P.M., and remained near the shore for further orders.

General Gillmore, on the 13th, began

constructing four batteries, mountain forty-two guns and mortars, to

damage the slopes and guns of Wagner, which were completed

under the enemy's fire, and in spite of a sortie at night, on the

14th. He expected to open with them on the 16th; but heavy

rains so delayed progress that all was not prepared until the 18th.

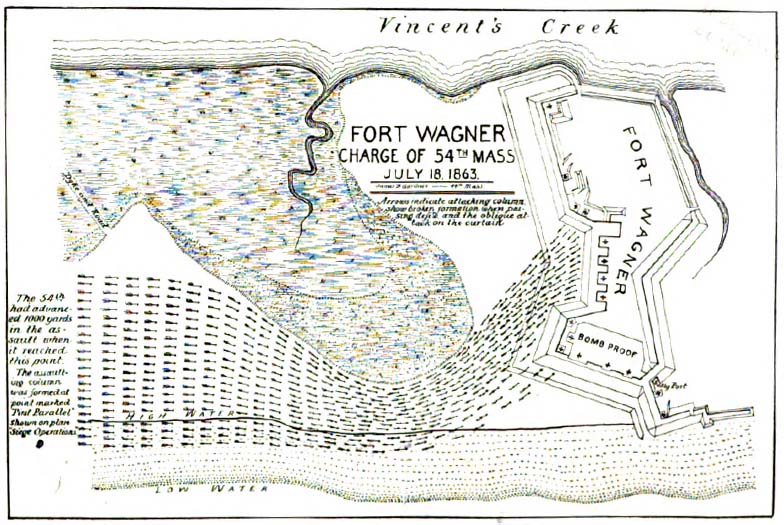

Beyond this siege line, which was 1,350 yards south of Wagner,

stretched a narrow strip of land between the sea and Vincent's

Creek, with its marshes. At low tide, the beach sand afforded

a good pathway to the enemy's position; but at high tide, it was

through deep, loose sand, and over low sand hillocks. This

stretch of sand was unobstructed, until at a point two hundred yards

in front of Wagner, the enemy had made a line of rifle trenches.

Some fifty yards nearer Wagner, an easterly bend of the marsh

extended to within twenty-five yards of the sea at high tide,

forming a defile, through which an assaulting column must pass.

[Page 69]

Nearly

covered by this sweep of the marsh, and commanding it as well as the

stretch of sand beyond to the Federal line, was "Battery Wagner," so

named by the Confederates, in memory of Lieut.-Col. Thomas M.

Wagner, First South Carolina Artillery, killed at Fort Sumter.

This field work was constructed of quartz sand, with turf and

palmetto log revetment, and occupied the whole width of the island

there, - some six hundred and thirty feet. Its southern and

principal front was double-bastioned. Next the sea was a heavy

traverse and curtain covering a sally-port. Then came the

southeast bastion, prolonged westerly by a curtain connected with

the southwest bastion. At the western end was another

sally-port. An infantry parapet closed the rear or north face.

It has large bombproofs, magazines, and heavy traverses.

Wagner's armament was reported to its commander,

July 15, as follows: on sea face, one ten-inch Columbiad, and two

smooth-bore thirty-two-pounders; on southeast bastion, operating on

land and sea, one rifled thirty-two-pounder; on south point of

bastion operating on land, one forty-two pounder carronade; in the

curtain, with direct fire on land approach to embrasure, two

eight-inch naval shell-guns, one eight-inch sea-coast howitzer, and

one thirty-two-pounder smooth-bore; on the flank defences of the

curtain, two thirty-two-pounder carronades in embrasures; on the

southerly face, one thirty-two-pounder carronade in embrasure; in

southwest angle, one ten-inch sea-coast mortar; on bastion gorge,

one thirty-two-pounder carronade. There were also four

twelve-pounder howitzers. All the northerly portion of Morris

Island was in range of Fort Sumter, the eastern James Island and the

[Page 70]

Sullivan's Island batteries, besides Fort Gregg, on the northerly

extremity of Morris Island, which mounted three guns.

Brig.-Gen. William B. Taliaferro, an able

officer, who had served with distinction under "Stonewall"

Jackson was in command of Morris Island, for the Confederates.

Wagner's garrison, on the 18th, consisted of the Thirty-first

and Fifty-first North Carolina, the Charleston Battalion, two

companies Sixty-third Georgia Heavy Artillery, and two companies

First South Carolina Infantry, acting as artillery, and two guns

each of the Palmetto and Blake's Artillery, - a total force of

seventeen hundred men. Such was the position, armament, and

garrison of the strongest single earthwork known in the history of

warfare.

About 10 A.M., on the 18th, five wooden gunboats joined

the land batteries in shelling Wagner, lying out of the

enemy's range. At about 12.30 P. M., five monitors and the

"New Ironsides" opened, and the land batteries increased their fire.

A deluge of shot was not poured into the work, driving the main

portion of its garrison into the bombproofs, and throwing showers of

sand from the slopes of Wagner into the air but to fall back in

place again. The enemy's flag was twice shot away, and, until

replaced, a battle-flag was planted with great gallantry by daring

men. From Gregg, Sumter, and the James and Sullivan's Island

batteries, the enemy returned the iron compliments; while for

a time Wagner's cannoneers ran out at intervals, and served a

part of the guns, at great risk.

A fresh breeze blew that day; at times the sky was

clear; the atmosphere, lightened by recent rains, resounded

[Page 71]

with the thunders of an almost incessant cannonade.

Smoke-clouds hung over the naval vessels, our batteries, and those

of the enemy. During this terrible bombardment, the two

infantry regiments and the artillery companies, except gun

detachments, kept in the bombproofs. But the Charleston

Battalion lay all day under the parapets of Wagner. - a

terrible ordeal, which was borne without demoralization. In

spite of the tremendous fire, the enemy's loss was only eight men

killed and twenty wounded before the assault.

General Taliaferro foresaw that this bombardment

was preliminary to an assault, and had instructed his force to take

certain assigned positions when the proper time came. Too

three companies of the Charleston Battalion was given the

Confederate right along the parapet; the Fifty-first North Carolina,

along the curtain; and the Thirty-first North Carolina, the left,

including the southeast bastion. Two companies of the

Charleston Battalion were placed outside the work, covering the

gorge. A small reserve was assigned to the body of the fort.

Two field-pieces were to fire from the traverse flanking the beach

face and approach. For the protection of the eight-inch

shell-guns in the curtain and the field-pieces, they were covered

with sand-bags, until desired for service. Thoroughly

conservant with the ground, the Confederate commander rightly

calculated that the defile would break up the formation of his

assailants at a critical moment, when at close range.

General Gillmore, at noon, ascended the lookout

on a hill within his lines, and examined the ground in front.

Throughout the day this high point was the gathering-place of

observers. The tide turned to flow at 4 P.M.,

[Page 72]

and about the same time firing from Wagner ceased, and not a

man was to be seen there. During the afternoon the troops were

moving from their camps toward the front. Late in the day the

belief was general that the enemy had been driven from his shelter,

and the armament of Wagner rendered harmless.

General Gillmore, after calling his chief officers together for

conference, decided to attack that evening, and the admiral was so

notified. Firing from land and sea was still kept up with

deceased rapidity, while the troops were preparing.

Upon arriving at Morris Island, Colonel Shaw and

Adjutant James walked toward the front to report to

General Strong, who they at last found, and who announced that

Fort Wagner was to be stormed that evening. Knowing Colonel

Shaw's desire to place his men beside white troops, he said,

"You may lead the column, if you say 'yes.' Your men, I known,

are worn out, but do as you chose." Shaw's face

brightened, and before replying, he requested Adjutant James

to return and have Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell bring up the

Fifty-fourth. Adjutant James, who relates this

interview, then departed on his mission. Receiving this order,

the regiment marched on to General Strong's headquarters,

where a halt of five minutes was made about 6 o'clock P.M.

Noticing the worn look of the men, who had passed two days without

an issue of rations, and no food since morning, when the weary march

began, the general expressed his sympathy and his great desire that

they might have food and stimulant. It could not be, however,

for it was necessary that the regiment should move on to the

position assigned.

Detaining Colonel Shaw to take supper with him,

[Page 73]

General Strong sent the Fifty-fourth forward under the

lieutenant-colonel toward the front, moving by the middle road west

of the sand-hills. Gaining a point where these elevations gave

place to low ground, the long blue line of the regiment advancing by

the flank attracted the attention of the enemy's gunners on James

Island. Several solid shot were fired at the column, without

doing any damage, but they recochetted ahead or over the line in

dangerous proximity. Realizing that the national colors and

the white flag of the State especially attracted the enemy's fire,

the bearers began to roll them up on the staves. At the

same moment, Captain Simpkins commanding the color company

(K) turned to observe his men. His quick eye noted the

half-furled flags with uplifted sword, he commanded in imperative

tones, "Unfurl those colors!" It was done, and the fluttering

silks again waved, untrammelled, in the air.

Colonel Shaw, at about 6:30 P.M., mounted and

accompanied General Strong toward the front. After

proceeding a short distance, he turned back, and gave to Mr.

Edward L. Pierce, a personal friend, who had been General

Strong's guest for several days, his letters and some papers,

with a request to forward them to his family if anything occurred to

him requiring such service. That sudden purpose accomplished,

he galloped away, overtook the regiment, and informed Lieutenant-Colonel

Hallowell of what the Fifty-fourth was expected to do.

The direction was changed to the right, advancing east toward the

sea. By orders, Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell broke the

column at the sixth company, and led the companies of

[Page 74]

the left wing to the rear of those of the right wing. When the

sea beach was reached, the regiment halted and came to rest,

awaiting the coming up of the supporting regiments.

General Gillmore had assigned to General

Seymour the command of the assaulting column, charging him with

its organization, formation, and all the details of the attack.

His force was formed into three brigades of infantry; the first

under General Strong, composed of the Fifty-fourth

Massachusetts, Sixth Connecticut, Forty-eighth New York, Third New

Hampshire, Ninth Maine, and Seventy-sixth Pennsylvania; the second,

under Col. Haldimand S. Putnam of his own regiment, - the

Seventh New Hampshire, - One Hundredth New York, Sixty-second and

Sixty-seventh Ohio; the third, or reserve brigade, under

Brig.-Gen. Thomas G. Stevenson of the Twenty-fourth

Massachusetts, Tenth Connecticut, Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania, and

Second South Carolina. Four companies of the Seventh

Connecticut, and some regular and volunteer artillery-men manned and

served the guns of the siege line.

Formed in column of wings, with the right resting near

the sea, at a short distance in advance of the works, the men of the

Fifty-fourth were ordered to lie down, there muskets loaded but not

capped, and bayonets fixed. There the regiment remained for

half an hour, while the formation of the storming column and reserve

was perfected. To the Fifty-fourth had been given the post of

honor, not by chance, but by deliberate selection. General

Seymour has stated the reasons why this honorable but dangerous

duty was assigned the regiment in the following words: -

[Page 75]

"It was believed that the Fifty-fourth was in every

respect as efficient as any other body of men; and as it was one of

the strongest and best officered, there seemed to be no good reason

why it should not be selected for the advance. This point was

decided by General Strong and myself.

In numbers

the Fifty-fourth had present but six hundred men, for besides the

large camp guard and the sick left at St. Helena Island, and the

losses sustained on James Island, on the 16th, a fatigue detail of

eighty men under Lieut. Francis L. Higginson did not

participate in the attack.

The formation of the regiment for the assault was, as

shown in the diagram below, with Companies B and E on the right of

the respective wings.

RIGHT WING.

K C I A B

LEFT WING.

H F G D E

Colonel

Shaw, Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell,

Adjutant James, seven captains, and twelve lieutenants, -

a total of twenty-two officers, advanced to the assault.

Surgeon Stone and Quartermaster Ritchie

were present on the field. Both field officers were

dismounted; the band and musicians acted as stretcher-bearers.

To many a gallant man these scenes upon the sands were

the last of earth; to the survivors they will be ever present.

Away over the sea to the eastward the heavy sea-fog was gathering,

the western sky bright with the reflected light, for the sun had

set. Far away thunder mingled with the occasional boom of

cannon. The gathering host all about, the silent lines

stretching away to the rear, the passing of a horseman now and then

carry-

[Page 76]

ing orders, - all was ominous of the impending onslaught. Far

and indistinct in front was the now silent earthwork, seamed,

scarred, and ploughed with shot, its flag still waving in defiance.

Among the dark soldiers who were to lead veteran

regiments which were equal in drill and discipline to any in the

country, there was a lack of their usual light-heartedness, for they

realized, partially at least, the dangers they were to encounter.

But there was little nervousness and no depression observable.

It took but a touch to bring out their irrepressible spirit and

humor in the old way. When a cannon-shot from the enemy came

toward the line and passed over, a man or two moved nervously,

calling out a sharp reproof from Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell, whom

the men still spoke of as "the major." Thereupon one soldier

quietly remarked to his comrades, "I guess the major forgets what

kind of balls them is!" Another added, thinking of the foe, "I

guess they kind of 'spec's we're coming.

Naturally the officers' thoughts were largely regarding

their men. Soon they would know whether the lessons they had

taught of soldierly duty would bear good fruit. Would they

have cause for exultation or be compelled to sheathe their swords,

rather than lead cowards Unknown to them, the whole question

of employing three hundred thousand colored soldiers hung in the

balance. But few, however, doubted the result. Wherever

a white officer led that night, even to the gun-muzzles and

bayonet-points, there, by his side, were black men as brave and

steadfast as himself.

At last the formation of the column was nearly

perfected. The Sixth Connecticut had taken position in

[Page 77]

column of companies just in rear of the Fifty-fourth. About

this time, Colonel Shaw walked back to Lieutenant-Colonel

Hallowell, and said "I shall go in advance with the National

flag. You will keep the State flag with you; it will give the

men something to rally round. We shall take the fort or die

there! Good-by!"

Presently, General Strong, mounted upon a

spirited gray horse, in full uniform, with a yellow handkerchief

bound around his neck, rode in front of the Fifty-fourth,

accompanied by two aids and two orderlies. He addressed the

men; and his words, as given by an officer of the regiment, were:

"Boys, I am a Massachusetts man, and I know you will fight for the

honor of the State. I am sorry you must go into the fight

tired and hungry, but the men in the fort are tired too. There

are but three hundred behind those walls, and they have been

fighting all day. Don't fire a musket on the way up, but go in

and bayonet them at their guns." Calling out the color-bearer,

he said, "If this man should fall, who will lift the flag and carry

it on?" Colonel Shaw, standing near, took a cigar from

between his lips, and said quietly, "I will." The men loudly

responded the Colonel Shaw's pledge, while General Strong

rode away to give the signal for advancing.

Colonel Shaw calmly walked up and down the line

of his regiment. He was clad in a close-fitting

staff-officer's jacket, with a silver eagle donoting his rank on

each shoulder. His trousers were light blue; a fine narrow

silk sash was wound round his waist beneath the jacket. Upon

his head was a high felt army hat with cord. Depending from

his sword-belt was a field-officer's sword of English manufacture,

with the initials of his name worked

[Page 78]

into the ornamentation of the guard. On his hand was

an antique gem set in a ring. In his pocket was a gold

watch, marked with his name, attached to a gold chain.

Although he had given certain papers and letters to his

friend, Mr. Pierce, he retained his pocket book,

which doubtless contained papers which would establish his

identity. His manner generally reserved before his

men, seemed to unbend to them, for he spoke as he had never

done before. He said, "Now I want you to prove

yourselves men," and reminded them that the eyes of

thousands would look upon the night's work. His

bearing was composed and graceful; his cheek had somewhat

paled; and the slight twitching of the corners of his mouth

plainly showed that the whole cost was counted, and his

expressed determination to take the fort or die was to be

carried out.

Meanwhile the twilight deepened, as the minutes, drawn

out by waiting, passed, before the signal was given.

Officers had silently grasped one another's hands, brought

their revolvers round to the front, and tightened their

sword-belts. The men whispered last injunctions to

comrades, and listened for the word of command.

The preparations usual in an assault were not made.

There was no provision for cutting away obstructions,

filling the ditch, or spiking the guns. No special

instructions were given the stormers; no line of skirmishers

or covering party was thrown out; no engineers or guides

accompanied the column; no artillery-men to serve captured

guns; no plan of the work was shown company officers.

It was understood that the fort would be assaulted with the

bayonet, and that the Fifty-fourth would be closely

supported.

[Page 79]

While on the

sands a few cannon-shots had reached the regiment, one passing

between the wings, another over to the right. When the

inaction had become almost unendurable, the signal to advance came.

Colonel Shaw walked along the front to the centre, and giving

the command, "Attention!" the men sprang to their feet. Then

came the admonition, "Move in quick time until within a hundred

yards of the fort; then double quick, and charge!" A slight

pause, followed by the sharp command, "forward!" and the

Fifty-fourth advanced to the storming.

There had been a partial resumption of the bombardment

during the formation, but now only an occasional shot was heard.

The enemy in Wagner had seen the preparations, knew what was coming,

and were awaiting the blow. With Colonel Shaw leading,

sword in hand, the long advance over three quarters of a mile of

sand had begun, with wings closed up and company officers

admonishing their men to preserve the alignment. Guns from

Sumter, Sullivan's Island, and James Island, began to play upon the

regiment. It was about 7.45 P.M., with darkness coming on

rapidly, when the Fifty-fourth moved. With barely room for the

formation from the first, the narrowing way between the sand

hillocks and the sea soon caused a strong pressure to the right, so

that Captains Willard and Emilio on the right of the

right companies of their wings were some of their men forced to

march in water up to their knees, at each incoming of the sea.

Moving at quick time, and preserving its formation as

well as the difficult ground and narrowing way permitted, the

Fifty-fourth was approaching the defile made by the easterly sweep

of the marsh. Darkness was rapidly com-

[Page 80]

lug on, and each moment became deeper. Soon men on the flanks

were compelled to fall behind, for want of room to continue in line.

The centre only had a free path, and with eyes strained upon the

colonel and the flag, they pressed on toward the work, now only two

hundred yards away.

At that moment Wagner became a mound of fire, from

which poured a stream of shot and shell. Just a brief lull,

and the deafening explosions of cannon were renewed, mingled with

the crash and rattle of musketry. A sheet of flame, followed

by a running fire, like electric sparks, swept along the parapet, as

the Fifty-first North Carolina gave a direct, and the Charleston

Battalion a left-oblique, fire on the Fifty-fourth. Their

Thirty-first North Carolina had lost heart, and failed to take

position in the southeast bastion, — fortunately, too, for had its

musketry fire been added to that delivered, it is doubtful whether

any Federal troops could have passed the defile.

When this tempest of war came, before which men fell in

numbers on every side, the only response the Fifty-fourth made to

the deadly challenge was to change step to the double-quick, that it

might the sooner close with the foe. There had been no stop,

pause, or check at any period of the advance, nor was there now.

As the swifter pace was taken, and officers sprang to the fore with

waving swords barely seen in the darkness, the men closed the gaps,

and with set jaws, panting breath, and bowed heads, charged on.

Wagner's wall, momentarily lit up by cannon-flashes,

was still the goal toward which the survivors rushed in sadly

diminished numbers. It was now dark, the gloom made more

intense by the blinding explosions in the

Fort Wagner Charge of 54th Mass.

July 18, 1863

[Page 81]

front. This terrible fire which the regiment had just faced,

probably caused the greatest number of casualties sustained by the

Fifty-fourth in the assault; for nearer the work the men were

somewhat sheltered by the high parapet. Every flash showed the

ground dotted with men of the regiment, killed or wounded.

Great holes, made by the huge shells of the navy or the land

batteries, were pitfalls into which the men stumbled or fell.

Colonel Shaw led the regiment to the left

toward the curtain of the work, thus passing the southeast bastion,

and leaving it to the right hand. From that salient no

musketry fire came; and some Fifty-fourth men first entered it, not

following the main body by reason of the darkness. As the

survivors drew near the work, they encountered the flanking fire

delivered from guns in the southwest salient, and the howitzers

outside the fort, which swept the trench, where further severe

losses were sustained. Nothing but the ditch now separated the

stormers and the foe. Down into this they went, through the

two or three feet of water therein, and mounted the slope beyond in

the teeth of the enemy, some of whom, standing on the crest, fired

down on them with depressed pieces. Both flags were planted on

the parapet, the national flag carried there and gallantly

maintained by the brave Sergt. William H. Carney of Company

C.

In the pathway from the defile to the fort many brave

men had fallen. Lieutenant-Colonel Hallowell was

severely wounded in the groin, Captain Willard in the

leg, Adjutant James in the ankle and side, Lieutenant

Romans in the shoulder. Lieutenants Smith and

Pratt were also wounded. Colonel Shaw had

led his regiment from first to last. Gaining the rampart, he

stood there for a mo-

[Page 82]

ment with uplifted sword, shouting, "Forward, Fifty-fourth!" and

then fell dead, shot through the heart, be sides other wounds.

Not a shot had been fired by the regiment up to this

time. As the crest was gained, the crack of revolver-shots was

heard, for the officers fired into the surging mass of upturned

faces confronting them, lit up redly but a moment by the

powder-flashes. Musket-butts and bayonets were freely used on the

parapet, where the stormers were gallantly met. The garrison

fought with muskets, handspikes, and gun-rammers, the officers

striking with their swords, so close were the combatants.

Numbers, however, soon told against the Fifty-fourth, for it was

tens against hundreds. Outlined against the sky, they were a

fair mark for the foe. Men fell every moment during the brief

struggle. Some of the wounded crawled down the slope to

shelter; others fell headlong into the ditch below.

It was seen from the volume of musketry fire, even

before the walls were gained, that the garrison was stronger than

had been supposed, and brave in defending the work. The first

rush had failed, for those of the Fifty-fourth who reached the

parapet were too few in numbers to overcome the garrison, and the

supports were not at hand to take full advantage of their first

fierce attack. Repulsed from the crest after the short

hand-to-hand struggle, the assailants fell back upon the exterior

slope of the rampart. There the men were encouraged to remain

by their officers, for by sweeping the top of the parapet with

musketry, and firing at those trying to serve the guns, they would

greatly aid an advancing force. For a time this was done, but

at the cost of more lives. The

[Page 83]

enemy's fire became more effective as the numbers of the

Fifty-fourth diminished. Hand grenades or lighted shells were

rolled down the slope, or thrown over into the ditch.

All this time the remaining officers and men of the

Fifty-fourth were firing at the hostile figures about the guns, or

that they saw spring upon the parapet, fire, and jump away.

One brave fellow, with his broken arm lying across his breast, was

piling cartridges upon it for Lieutenant Emerson, who,

like other officers, was using a musket he had picked up.

Another soldier, tired of the enforced combat, climbed the slope to

his fate; for in a moment his dead body rolled down again. A

particularly severe fire came from the southwest bastion.

There a Confederate was observed, who, stripped to the waist, with

daring exposure for some time dealt out fatal shots; but at last

three eager marksmen fired together, and he fell back into the fort,

to appear no more. Capt. J. W. M. Appleton

distinguished himself before the curtain. He crawled into an

embrasure, and with his pistol prevented the artillery-men from

serving the gun. Private George Wilson of Company A had

been shot through both shoulders, but refused to go back until he

had his captain's permission. While occupied with this

faithful soldier, who came to him as he lay in the embrasure,

Captain Anderson's attention was distracted, and the gun was

fired.

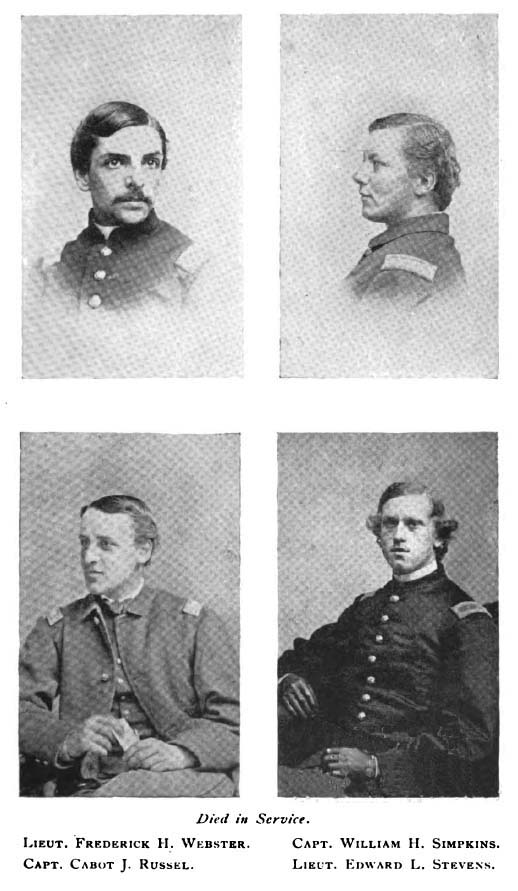

In the fighting upon the slopes of Wagner, Captains

Russel and Simpkins were killed or mortally wounded.

Captain Pope there received a severe wound in the shoulder.

All these events had taken place in a short period of

[Page 84]

time. The charge of the Fifty-fourth had been made and

repulsed before the arrival of any other troops. Those who had

clung to the bloody slopes or were lying in the ditch, hearing

fighting going on at their right, realized at last that the expected

succor would not reach them where they were. To retire through

the enveloping fire was as dangerous and deadly as to advance.

Some that night preferred capture to the attempt at escaping; but

the larger portion managed to fall back, singly or in squads, beyond

the musketry fire of the garrison.

Captain Emilio, the junior of that rank,

succeeded to the command of the Fifty-fourth on the field by

casualties. After retiring from Wagner to a point where men

were encountered singly or in small squads, he determined to rally

as many as possible. With the assistance of Lieutenants

Grace and Dexter, a large portion of the Fifty-fourth

survivors were collected and formed in line, together with a

considerable number of white soldiers of various regiments.

Wile thus engaged, the national flag of the Fifty-fourth was brought

to Captain Emelio; but as it was useless as a rallying-point

in the darkness, it was sent to the rear for safety.

Sergeant CArney had bravely brought this flag from Wagner's

parapet, at the cost of two grievous wounds. The State color

was torn from the staff, the silk was found by the enemy in the

moat, while the staff remained with us.

Finding a line of rifle trench unoccupied and no

indication that dispositions were being made for holding it,

believing that the enemy would attempt a sortie, which was indeed

contemplated but not attempted, Captain Emilio there

stationed his men, disposed to defend the line. Other men were

collected as they appeared. Lieut-

[Page 85]

tenant Tucker, slightly wounded, who was among the

last to leave the sand hills near the fort, joined this force.

Desultory firing was still going

on, and after a time,

[Page 86]

[Page 87]

[Page 88]

[Page 89]

[Page 90]

[Page 91]

[Page 92]

[Page 93]

[Page 94]

[Page 95]

[Page 96]

black soldiers had been captured. Under the acts of the

Confederate Congress they were outlaws, to be delivered to the State

authorities when captured, for trial; and the penalty of servile

insurrection was death.

The fate of Captains Russel and

Simpkins was also unknown. It was thought possible that

they too were captured. Governor Andrew and the

friends of the regiment therefore exerted themselves to have the

Government throw out its protecting hand over its colored soldiers

and their officers in the enemy's hands.

Two sections were at once added to General Orders No.

100 of the War Department, relating to such prisoners, a copy of

which was transmitted to the Confederate commissioner, Robert

Ould. The first set forth that once a soldier no man

was responsible individually for warlike acts; the second, that the

law of nations recognized no distinctions of color, and that if the

enemy enslaved or sold the captured soldier, as the United States

could not enslave, death would be the penalty in retaliation.

The President also met the case in point involving the Fifty-fourth

prisoners, by issuing the following proclamation:

Executive Mansion, Washington, July 80, 1863.

It is the duty of every

government to give protection to its citizens of whatever class,

color, or condition, and especially to those who are duly organized

as soldiers in the public service. The law of nations and the

usages and customs of war, as carried on by civilized powers, permit

no distinction as to color in the treatment of prisoners of war as

public enemies. To sell or enslave any captured person on

account of his color, and for no offence against the laws of war, is

a relapse into barbarism and a crime against the civilization of the

age. The Government of the United States will give the same

protection

LIEUT. FREDERICK H. WEBSTER

CAPT. WILLIAM H. SIMPKINS

CAPT. CABUT J. RUSSEL

LIEUT. EDWARD L. STEVENS

[Page 97]

to all its soldiers; and if the enemy shall sell or enslave any one

because of his color, the offence shall be punished by retaliation

upon the enemy's prisoners in our hands.

It is therefore ordered that for every soldier of the

United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a Rebel

soldier shall be executed, and for every one enslaved by the enemy

or sold into slavery, a Rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor

on the public works, and continue at such labor until the other

shall be released and receive the treatment due a prisoner of war.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN.

By order of the Secretary of War,

E. D. TOWNSEND, Assistant Adjutant-General.

Such prompt

and vigorous enunciations had a salutary effect; and the enemy did

not proceed to extremities. But the Fifty-fourth men were

demanded by Governor Bonham, of South Carolina, from the

military authorities. A test case was made; and Sergt.

Walter A. Jeffries of Company H, and Corp. Charles

Hardy of Company B, were actually tried for their lives.

They were successfully defended by the ablest efforts of one of the

most brilliant of Southern advocates, the Union-loving and noble

Nelson Mitchell, of Charleston, who, with a courage

rarely equalled, fearlessly assumed the self-imposed task.

Thence forth never noticed, this devoted man died a few months after

in Charleston, neglected and in want, because of this and other

loyal acts. For months no list could be obtained of the

Fifty-fourth prisoners, the enemy absolutely refusing information.

After long imprisonment in Charleston jail, they were taken to

Florence stockade, and were finally released in the spring of 1865.

The best attainable information shows that the survivors then

numbered some twenty-seven, some of whom rejoined the regi-

[Page 98]

ment, while others were discharged from parole camps or hospitals.

Colonel Shaw's fate was soon ascertained

from those who saw him fall, and in a day or two it was learned from

the enemy that his body had been found, identified, and, on July 19,

buried with a number of his colored soldiers. The most

circumstantial account relating thereto is contained in a letter to

the writer from Capt. H. W. Hendricks, a Confederate officer

who was present at the time, dated from Charleston, S. C, June 29,

1882; and the following extracts are made therefrom: —

"... Colonel

Shaw fell on the left of our flagstaff about ten yards towards

the river, near the bombproof immediately on our works, with a

number of his officers and men. He was instantly killed, and

fell outside of our works. The morning following the battle

his body was carried through our lines; and I noticed that he was

stripped of all his clothing save under-vest and drawers. This

desecration of the dead we endeavored to provide against; but at

that time — the incipiency of the Rebellion — our men were so

frenzied that it was next to impossible to guard against it; this

desecration, however, was almost exclusively participated in by the

more desperate and lower class of our troops. Colonel

Shaw's body was brought in from the sally-port on the

Confederate right, and conveyed across the parade-ground into the

bombproof by four of our men of the burial party. Soon after,

his body was carried out via the sally-port on the left river-front,

and conveyed across the front of our works, and there buried. . . .

His watch and chain were robbed from his body by a private in my

company, by name Charles Blake. I think he had

other personal property of Colonel Shaw. . . .

Blake, with other members of my company, jumped our works at

night after hostilities had ceased, and robbed the dead. . . .

Colonel Shaw was the only officer buried with the colored

troops. . . ."

[Page 99]

Such disposal of the remains of an officer of Colonel Shaw's

rank, when his friends were almost within call, was so unusual and

cruel that there seemed good ground for the belief that the

disposition made was so specially directed, as a premeditated

indignity for having dared to lead colored troops. When known

throughout the North, it excited general indignation, and fostered

bitterness. Though recognizing the fitness of his

resting-place, where in death he was not separated from the men he

was in life not ashamed to lead, the act was universally condemned.

It was even specifically stated in a letter which appeared in the

"Army and Navy Journal," of New York City, written by Asst.-Surg.

John T. Luck, U. S. N., who was captured while engaged in

assisting our wounded during the morning of July 19, that Gen.

Johnson Hagood, who had succeeded General Taliaferro in

command of Battery Wagner that morning, was responsible for the

deed. The following is extracted from that letter: —

". . . While being

conducted into the fort, I saw Colonel Shaw of the Fifty-four

Massachusetts (colored) Regiment lying dead upon the ground just

outside the parapet. A stalwart negro man had fallen near him.

The Rebels said the negro was a color sergeant. The colonel

had been killed by a rifle-shot through the chest, though he had

received other wounds. Brigadier-General

Hagood, commanding the Rebel forces, said to me: 'I knew

Colonel Shaw before the war, and then esteemed him.

Had he been in command of white troops, I should have given him an

honorable burial; as it is, I shall bury him in the common trench

with the negroes that fell with him.' The burial party were

then at work; and no doubt Colonel Shaw was

buried just beyond the ditch of the fort in the trench where

[Page 100]

I saw our dead indiscriminately thrown. Two days afterwards a

Rebel surgeon (Dr. Dawson, of Charleston, S. C, I

think) told me that Hagood had carried out his threat."

Assistant-Surgeon Luck's statement is, however,

contradicted by General Hagood; for having requested

information upon the matter, the writer, in December, 1885, received

from Gen. Samuel Jones, of Washington, a copy

of a letter written by Gen. Johnson Hagood to

Col. T. W. Higginson, of Cambridge, Mass., dated Sept.

21, 1881. General Hagood quotes from Colonel

Higginson's letter of inquiry relative to Colonel

Shaw's burial, the conversation which Assistant-Surgeon

Luck alleges to have had with him at Battery Wagner about the

disposition of Colonel Shaw's body, as set forth in

the extract given from Assistant-Surgeon Luck's

letter, and then gives his (General Hagood's) account

of the meeting with Assistant-Surgeon Luck as

follows, the italics being those of the general : —

"On the day after the night assault and while the

burial parties of both sides were at work on the field, a chain of

sentinels dividing them, a person was brought to me where I was

engaged within the battery in repairing damages done to the work.

The guard said he had been found wandering within our lines, engaged

apparently in nothing except making observations. The man

claimed to be a naval surgeon belonging to gunboat 'Pawnee;' and

after asking him some questions about the damages sustained by that

vessel a few days before in the Stono River from an encounter with a

field battery on its banks, I informed him that he would be sent up

to Charleston for such disposition as General Beauregard

deemed proper. I do not recall the name of this person,

and have not heard of him since, but he must be the Dr.

Leech [Luck?] of whom you speak. I

[Page 101]

have no recollection of other conversation with him than that

given above. He has, however, certainly reported me

incorrectly in one particular. I never saw or heard of

Colonel Shaw until his body was pointed out to me that

morning, and his name and rank mentioned. . . . I simply give my

recollection in reply to his statement. As he has confounded

what he probably heard from others within the battery of their

previous knowledge of Colonel Shaw, he may at the distance of

time at which he spoke have had his recollection of his interview

with me confounded in other respects.

"You further ask if a request from General

Terry for Colonel Shaw's body was refused the day after

the battle. I answer distinctly, No. At the written

request of General Gillmore, I, as commander of the

battery, met General Vogdes (not Terry), on a

flag of truce on the 22d. Upon this flag an exchange of

wounded prisoners was arranged, and Colonel Putnam's

body was asked for and delivered. Colonel Shaw's

body was not asked for then or at any other time to my knowledge. .

. . No special order was ever issued by me, verbally or

otherwise, in regard to the burial of Colonel Shaw or

any other officer or man at Wagner. The only order was a

verbal one to bury all the dead in trenches as speedily as possible,

on account of the heat; and as far as I knew then, or have reason to

believe now, each officer was buried where he fell, with the men who

surrounded him. It thus occurred that Colonel Shaw,

commanding negroes, was buried with negroes."

These extracts from the

letters of Assistant-Surgeon Luck and General

Hagood are submitted to the reader with the single suggestion

that what is said about Colonel Shaw's body being brought

into Fort Wagner, contained in Captain Hendricks's

letter, should be borne in mind while reading the latter portion of

the extracts from General Hagood's letter.

But how far General Hagood may be held

responsible

[Page 102]

for the lack of generous and Christian offices to the re mains of

Colonel Shaw, his family and comrades, is another matter.

And the writer submits that these faults of omission are grave; that

the acknowledged bravery of Colonel Shaw in life, and

his appearance even in death, when, as General Hagood

acknowledges, "his body was pointed out to me that morning," should

have secured him a fitting sepulture, or the tender of his body to

his friends. This burial of Colonel Shaw,

premeditated and exceptional, was without question intended as an

ignominy. It served to crown the sacrifices of that young

life, so short and eventful, and to place his name high on the roll

of martyrs and leaders of the Civil War.

Colonel Shaw's sword was found during the

war in a house in Virginia, and restored to his family. His

silk sash was purchased in Battery Wagner from a private soldier, by

A. W. Muckenfuss, a Confederate officer, who, many years

after, generously sent it North to Mr. S. D. Gilbert, of

Boston, for restoration to the Shaw family.

Only these two articles have been recovered, so far as known.

No effort was made to find Colonel Shaw's

grave when our forces occupied the ground. This was in

compliance with the request contained in the following letter : —

NEW

YORK, Aug. 24, 1863.

BRIGADIER-GENERAL GILLMORE, Commanding

Department of the South.

SIR, — I take the liberty to address you because I am

in formed that efforts are to be made to recover the body of my son,

Colonel Shaw of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts

Regiment, which was buried at Fort Wagner. My object in

writing is to say that such efforts are not authorized by me or any

of my family, and that they are not approved by us. We hold

that a

[Page 103]

soldier's most appropriate burial-place is on the field where he has

fallen. I shall therefore be much obliged, General, if in case

the matter is brought to your cognizance, you will forbid the

desecration of my son's grave, and prevent the disturbance of his

remains or those buried with him. With most earnest wishes for

your success, I am, sir, with respect and esteem,

Your obedient servant,

FRANCIS GEORGE SHAW.

Captains Russel and

Simpkins were doubtless interred with other white soldiers,

after their bodies had been robbed of all evidences of their rank

during the hours of darkness.

After all firing had ceased, about midnight,

Brig.-Gen. Thomas G. Stevenson, commanding the front lines,

ordered two companies of the Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania, under

Lieutenant-Colonel Duer, to advance from the abatis as

skirmishers toward Wagner, followed by four companies of the

Ninety-seventh, without arms, under Captain Price, to rescue

the wounded. General Stevenson saw to this

service personally, and gave special instructions to rescue as many

as possible of the Fifty-fourth, saying, "You know how much harder

they will fare at the hands of the enemy than white men." The

rescuing party, with great gallantry and enterprise, pushed the

search clear up to the slopes of Wagner, crawling along the ground,

and listening for the moans that indicated the subjects of their

mission. When found, the wounded were quietly dragged to

points where they could be taken back on stretchers in safety.

This work was continued until daylight, and many men gathered in by

the Ninety-seventh; among them was Lieutenant Smith of

the Fifty-fourth. It was a noble work fearlessly done.

[Page 104]

Throughout the assault

and succeeding night, Quartermaster Ritchie was active and

efficient in rendering help to the wounded of the regiment and

endeavoring to ascertain the fate of Colonel Shaw and other

officers. Surgeon Stone skilfully aided all

requiring his services, sending the severely wounded men and

officers from temporary hospitals to the steamer "Alice Price."

|