|

HISTORY of the FIFTY-FOURTH REGIMENT

of

MASSACHUSETTS VOLUNTEER INFANTRY

1863-1865

by Luis Fenollosa Emilio

Published:

Boston:

The History Book Company

1894.

----------

CHAPTER VI.

SIEGE OF WAGNER

[Page 105]

EARLY on the

morning of July 19, the men of the fifty-fourth were aroused, and

the regiment marched down the beach, making camp near the southern

front of the island at a point where the higher hills give way to a

low stretch of sand bordering the inlet. On this spot the

regiment remained during its first term of service, at Morris

Island.

That day was the saddest in the history of the

Fifty-fourth, for the depleted ranks bore silent witness to the

severe losses of the previous day. Men who had wandered to

other points during the night continued to join their comrades until

some four hundred men were present. A number were without

arms, which had either been destroyed or damaged in their hands by

shot and shell, or were thrown away in the effort to save life.

The officers present for duty were Captain Emilio,

commanding, Surgeon Stone, Quartermaster

Ritchie, and Lieutenants T. W. Appleton, Grace,

Dexter, Jewett, Emerson, Reid, Tucker,

Johnston, Howard, and Higginson.

Some fifty men, slightly wounded, were being treated in

camp. The severely wounded, including seven officers, were

taken on the 19th to hospitals at Beaufort, where every care was

given them by the medical men, General Saxton, his officers,

civilians, and the colored people.

[Page 106]

By order of

General Terry, commanding Morris Island, the regiment

on the 19th was attached to the Third Brigade with the Tenth

Connecticut, Twenty-fourth Massachusetts, Seventh New Hampshire, One

Hundredth New York, and Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania, under

General Stevenson. Upon the 20th the labors of the

siege work began, for in the morning the first detail was furnished.

Late in the afternoon the commanding officer received orders to take

the Fifty-fourth to the front for grand-guard duty. He

reported with all the men in camp — some three hundred — and was

placed at the Beacon house, supporting the Third New Hampshire and

Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania. There was no firing of

consequence that night. In the morning the Fifty-fourth was

moved forward into the trenches.

Capt. D. A. Partridge, left sick in

Massachusetts, joined July 21, and, as senior officer, assumed

command.

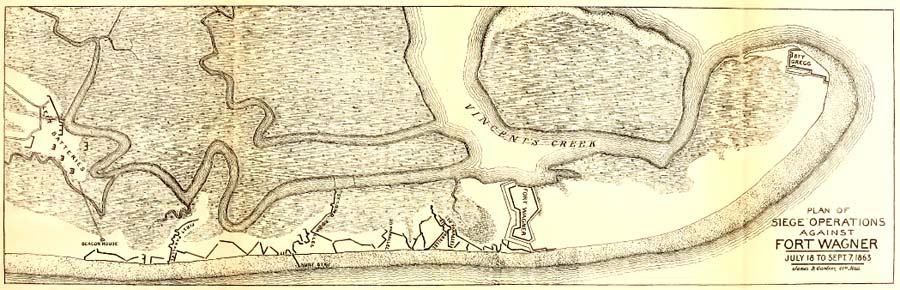

Preparations were made for a bombardment of Sumter as

well as for the siege of Wagner. Work began on the artillery

line of July 18, that night, for the first parallel, 1,350 yards

from Wagner. When completed, it mounted eight siege and field

guns, ten mortars, and three Requa rifle batteries. July 23,

the second parallel was established some four hundred yards in front

of the first. Vincent's Creek on its left was obstructed with

floating booms. On its right was the "Surf Battery," armed

with field-pieces. This parallel was made strong for defence

for the purpose of constructing in its rear the "Left Batteries"

against Sumter. It mounted twenty-one light pieces for defence

and three thirty-pounder Parrotts and one Wiard rifle. The two

parallels were connected by zigzag approaches to protect passing

troops. In the construction of these works and the

transportation of siege material, ordnance, and

[Page 107]

quartermaster's stores, the Fifty-fourth was engaged, in common with

all the troops on the island, furnishing large details. So many men

were called for that but a small camp guard could be maintained, and

at times non-commissioned officers volunteered to stand on post.

Col. M. S. Littlefield, Fourth South Carolina

Colored, on July 24, was temporarily assigned to command the

Fifty-fourth. The colonel's own regiment numbered but a few

score of men, and this appointment seemed as if given to secure him

command commensurate with the rank he held. It gave rise to

much criticism in Massachusetts as well as in the regiment, for it

was made contrary to custom and without the knowledge of Governor

Andrew. Though silently dissatisfied, the officers

rendered him cheerful service.

Anticipating a bombardment of Sumter, the enemy were

busy strengthening the gorge or south wall with both cotton-bales

and sand-bags. A partial disarmament of the fort was being

effected. Wagner was kept in repair by constant labor at

night. To strengthen their circle of batteries the enemy were

busy upon new works on James Island. About 10 a. m., on the

24th, the Confederate steamer "Alice" ran down and was met by the

"Cosmopolitan," when thirty-eight Confederates were given up, and we

received one hundred and five wounded, including three officers.

There was complaint by our men that the Confederates had neglected

their wounds, of the unskilful surgical treatment received, and that

unnecessary amputations were suffered. From Col. Edward C.

Anderson it was ascertained that the Fifty-fourth's prisoners

would not be given up, and Colonel Shaw's death was

confirmed.

[Page 108]

Battery

Simkins on James Island opened against our trenches for the first

time on the 25th. For the first time also sharpshooters of the enemy

fired on our working parties with long-range rifles. Orders

came on the 26th that, owing to the few officers and lack of arms,

the Fifty-fourth should only furnish fatigue details.

Quartermaster Ritchie, who was sent to Hilton Head,

returned on the 29th with the officers, men, and camp equipage from

St. Helena, and tents were put up the succeeding day. Some six

hundred men were then present with the colors, including the sick.

The number of sick in camp was very large, owing to the severe work

and terrible heat. About nineteen hundred were reported on

August 1 in the whole command. The sight of so many pale,

enfeebled men about the hospitals and company streets was

dispiriting. As an offset, some of those who had recovered

from wounds returned, and Brig.-Gen. Edward A. Wild's brigade

of the First North Carolina and Fifty-fifth Massachusetts, both

colored, arrived and camped on Folly Island.

Mr. De Mortie, the regimental

sutler, about this time brought a supply of goods. After

August 2 the details were somewhat smaller, as the colored brigade

on Folly-Island began to send over working parties. But calls

were filled from the regiment daily for work about the landing and

the front. Two men from each company reported as sharpshooters

in conjunction with those from other regiments.

The famous battery known as the "Swamp Angel" was begun

August 4, and built under direction of Col. E. W. Serrell,

First New York Engineers, and was situated in the marsh between

Morris and James islands. It was constructed upon a foundation

of timber, with sand-bags

[Page 109]

filled upon Morris Island and taken out in boats. A

two-hundred-pounder Parrott gun was lightered out to the work at

night with great difficulty. Its fire reached Charleston, a

distance of 8,800 yards. This gun burst after the first few

discharges. Later, two mortars were mounted in the work in

place of the gun. Capt. Lewis S. Payne, One Hundredth

New York, the most daring scout of our forces, at night, August 3,

while at Payne's dock, was captured with a few men.

August 5 the men were informed that the Government was

ready to pay them $10 per month, less $3 deducted for clothing.

The offer was refused, although many had suffering families.

About this time a number of men were detached, or detailed, as

clerks, butchers, and as hands on the steamers "Escort" and

"Planter." Work was begun on the third parallel within four

hundred yards of Wagner on the night of the 9th. When

completed, it was one hundred yards in length, as the island

narrowed. Water was struck at a slight depth. The

weather was excessively hot, and flies and sand-fleas tormenting.

Only sea-bathing and cooler nights made living endurable. The

Fifty-fourth was excused from turning out at reveille in consequence

of excessive work, for we were daily furnishing parties reporting to

Lieut. P S. Michie, United States Engineers, at the Left

Batteries, and to Colonel Serrell at the " Lookout."

Fancied security of the Fifty-fourth camp so far from

the front was rudely dispelled at dark on August 13 by a shell from

James Island bursting near Surgeon Stone's tent.

These unpleasant visits were not frequent, seemingly being efforts

of the enemy to try the extreme range of their guns.

Reinforcements, consisting of Gen. George H. Gor

[Page 110]

don's division from the Eleventh Corps, arrived on the 13th

and landed on the 15th upon Folly Island. No rain fell from

July 18 until August 13, which was favorable for the siege work, as

the sand handled was dry and light. This dryness, however,

rendered it easily displaced by the wind, requiring constant labor

in re-covering magazines, bombproofs, and the slopes. The air

too was full of the gritty particles, blinding the men and covering

everything in camp.

By this date twelve batteries were nearly ready for

action, mounting in all twenty-eight heavy rifles, from thirty to

three hundred pounders, besides twelve ten-inch mortars. Those

for breaching Sumter were at an average distance of 3,900 yards.

Detachments from the First United States Artillery, Third Rhode

Island Artillery, One Hundredth New York, Seventh Connecticut,

Eleventh Maine, and the fleet, served the guns. These works

had been completed under fire from Sumter, Gregg, Wagner, and the

James Island batteries, as well as the missiles of sharpshooters.

Most of the work had been done at night. Day and night heavy

guard details lay in the trenches to repel attack. The labor

of transporting the heavy guns to the front was very great, as the

sinking of the sling-carts deep into the sand made progress slow.

Tons of powder, shot, and shell had been brought up, and stored in

the service-magazines. It was hoped by General

Gillmore that the demolition of Sumter would necessitate the

abandonment of Morris Island, for that accomplished, the enemy could

be prevented from further relief of the Morris Island garrison.

Sumter was then commanded by Col. Alfred Rhett, First South

Carolina Artillery; and the garrison was of his regiment. In

all this work preparatory to breaching Sumter the Fifty-

[Page 111]

fourth had borne more than its share of labor, for it was

exclusively employed on fatigue duty, which was not the case with

the white troops. There had been no time for drill or

discipline. Every moment in camp was needed to rest the

exhausted men and officers. The faces and forms of all showed

plainly at what cost this labor was done. Clothes were in

rags, shoes worn out, and haversacks full of holes. On the

16th the medical staff was increased by the arrival of Asst.-Surg.

G. M. Pease. Lieut. Charles Silva, Fourth South

Carolina (colored), was detached to the Fifty-fourth on the 21st,

doing duty until November 6.

Shortly after daybreak, August 17, the first

bombardment of Sumter began from the land batteries, the navy soon

joining in action. The fire of certain guns was directed

against Wagner and Gregg. Capt. J. M. Wampler, the engineer

officer at Wagner, and Capt. George W. Rodgers and

Paymaster Woodbury of the monitor "Catskill" were killed.

Sumter was pierced time and again until the walls looked like a

honeycomb. All the guns on the northwest face were disabled,

besides seven others. A heavy gale came on the 18th, causing a

sand-storm on the island and seriously interfering with gun

practice. Wagner and Gregg replied slowly. Lieut.

Henry Holbrook, Third Rhode Island Heavy Artillery,

was mortally wounded by a shell.

By premature explosion of one of our shells, Lieut.

A. F. Webb, Fortieth Massachusetts, was killed and several men

wounded at night on the 19th. The water stood in some of the

trenches a foot and a half deep. Our sap was run from the left

of the third parallel that morning. The One Hundredth New

York, Eighty-fifth Pennsylvania, and

[Page 112]

Third New Hampshire were detailed as the guard of the advance

trenches. An event of the 20th was the firing for the first

time of the great three-hundred-pounder Parrott. It broke down

three sling-carts, and required a total of 2,500 days' labor before

it was mounted. While in transit it was only moved at night,

and covered with a tarpaulin and grass during the daytime. The

enemy fired one hundred and sixteen shots at the Swamp Angel from

James Island, but only one struck. Sumter's flag was shot away

twice on the 20th. All the guns on the south face were

disabled. Heavy fire from land and sea continued on the 21st,

and Sumter suffered terribly.

A letter from Gillmore to Beauregard was

sent on the 21st, demanding the surrender of Morris Island and

Sumter, under penalty, if not complied with, of the city being

shelled. The latter replied, threatening retaliation.

Our fourth parallel was opened that night 350 yards from Wagner, and

the One Hundredth New York unsuccessfully attempted to drive the

enemy's pickets from a small ridge two hundred yards in front of

Wagner. The Swamp Angel opened on Charleston at 1.30 a. m. on

the 22d. By one shell a small fire was started there.

Many non-combatants left the city. Wagner now daily gave a

sharp fire on our advanced works to delay progress. The "New

Ironsides" as often engaged that work with great effect. Late

on the 22d a truce boat came from Charleston, causing firing to be

temporarily suspended.

Although almost daily the Fifty-fourth had more or less

men at the front, it had suffered no casualties. The men were

employed at this period in throwing up parapets, enlarging the

trenches, covering the slopes, turfing the batteries, filling

sand-bags, and other labors incident to the

[Page 113]

operations. In the daytime two men were stationed on higher

points to watch the enemy's batteries. Whenever a puff of

smoke was seen these "lookouts" called loudly, "Cover!" adding the

name by which that particular battery was known. Instantly the

workers dropped shovels and tools, jumped into the trench, and,

close-covered, waited the coming of the shot or shell, which having

exploded, passed, or struck, the work was again resumed. Some

of the newer batteries of the enemy were known by peculiar or

characteristic names, as "Bull in the Woods," "Mud Digger," and

"Peanut Battery." At night the men, worked better, for the

shells could be seen by reason of the burning fuses, and their

direction taken; unless coming in the direction of the toilers, the

work went on. Becoming accustomed to their exposure, in a

short time this "dodging shells" was reduced almost to a scientific

calculation by the men. Most of all they dreaded

mortar-shells, which, describing a curved course in the sky, poised

for a moment apparently, then, bursting, dropped their fragments

from, directly overhead. Bomb or splinter proofs alone

protected the men from such missiles, but most of the work was in

open trenches. Occasionally solid shot were thrown, which at

times could be distinctly seen bounding over the sand hills, or

burying themselves in the parapets.

Our batteries and the navy were still beating down the

walls of Sumter on the 23d, their shots sweeping through it.

That day Colonel Rhett, the commander, and four other

officers were there wounded. With Sumter in ruins, the breaching

fire ceased that evening, and General Gillmore

reported that he "considered the fort no longer a fit work from

which to use artillery." He then deemed his part of the work

against Charleston accomplished, and ex

[Page 114]

pected that the navy would run past the batteries into the harbor.

Admiral Dahlgren and the Navy Department thought

otherwise, declining to risk the vessels in the attempt.

Captain Partridge about August 23 applied

for sick leave and shortly went north. In consequence

Captain Emilio again became the senior officer and was at

times in charge of the regiment until the middle of October.

On the 23d the brigade was reviewed on the beach by General

Gillmore, accompanied by General Terry.

The latter complimented the Fifty-fourth on its appearance.

That evening Captain Emilio and Lieutenant

Higginson took one hundred and fifty men for grand guard,

reporting to Col. Jos. R. Hawley, Seventh Connecticut,

field-officer of the trenches. This was the first detail other

than fatigue since July 21. The detachment relieved troops in

the second parallel. During the night it was very stormy, the

rain standing in pools in the trenches. But few shots were

fired. Charleston's bells could be heard when all was still.

At midnight the Swamp Angel again opened on the city. About 10

a.m., on the 24th, Wagner and Johnson both opened on us, the former

with grape and canister sweeping the advanced works. In the

camp, by reason of rain and high tides, the water was several inches

deep in the tents on lowest ground. A new brigade — the Fourth

— was formed on the 24th, composed of the Second South Carolina,

Fifty-fourth Massachusetts, and Third United States Colored Troops

(the latter a new regiment from the north), under Colonel

Montgomery.

About dark on the 25th a force was again advanced

against the enemy's picket, but was repulsed. It was found

that a determined effort must be made to carry the sand ridge

crowned by the enemy's rifle-pits. Just before dark

[Page 115]

the next day, therefore, a concentrated fire was maintained against

this position for some time. Col. F. A. Osborn,

Twenty-fourth Massachusetts, with his regiment, supported by the

Third New Hampshire, Capt. Jas. F. Randlett, then advanced

and gallantly took the line in an instant, the enemy only having

time to deliver one volley. They captured sixty-seven men of

the Sixty-first North Carolina. Cover was soon made, a task in

which the prisoners assisted to insure their own safety. The

Twenty-fourth lost Lieut. Jas. A. Perkins and two enlisted

men killed, and five wounded. Upon this ridge, two hundred

yards from Wagner, the fifth parallel was immediately opened.

Beyond it the works, when constructed, were a succession of short

zigzags because of the narrow breadth of the island and the flanking

and near fire of the Confederates. Our fire was being more

directed at Wagner, which forced its garrison to close their

embrasures in the daytime. It had also become more difficult

to send their customary relieving force every third day to Morris

Island. Fire upon us from the James Island batteries on the

left became very troublesome, occasioning numerous casualties.

Our own mortar-shells, on the 27th, in the evening killed seven men,

and wounded two of the Eighty-fifth Pennsylvania.

That night there was a severe thunder-storm drenching

everything in camp and leaving pools of water in the tents. A

warm drying sun came out on the 28th. In the evening there was

some disturbance, soon suppressed, in consequence of ill feeling

toward the regimental sutler. In the approaches work was slow

by reason of the high tides and rain. Moonlight nights

interfered also, disclosing our working parties to the enemy.

Colonel Montgomery, commanding the brigade, on the

29th established his head

[Page 116]

quarters near the right of our camp. It was learned that a

list of prisoners recently received from the enemy contained no

names of Fifty-fourth men. On the 30th Lieut.-Col. Henry A.

Purviance, Eighty-fifth Pennsylvania, was killed by the

premature explosion of one of our own shells. The enemy's

steamer "Sumter," returning from Morris Island early on the 31st

with six hundred officers and men, was fired into by Fort Moultrie,

and four men were killed or drowned.

With our capture of the ridge on the 26th the last

natural cover was attained. Beyond for two hundred yards

stretched a strip of sand over which the besiegers must advance.

It seemed impossible to progress far, as each attempt to do so

resulted in severe losses. Every detail at the front

maintained its position only at the cost of life. So numerous

were the dead at this period of the siege that at almost any hour

throughout the day the sound of funeral music could be heard in the

camps. Such was the depressing effect upon the men that

finally orders were issued to dispense with music at burials.

The troops were dispirited by such losses without adequate results.

That the strain was great was manifested by an enormous sick list.

It was the opinion of experienced officers that the losses by

casualties and sickness were greater than might be expected from

another assault.

Success or defeat seemed to hang in the balance.

Under no greater difficulties and losses many a siege had been

raised. General Gillmore, however, was equal to

the emergency. He ordered the fifth parallel enlarged and

strengthened, the cover increased, and a line of rifle trench run in

front of it. New positions were constructed for the

sharpshooters. All his light mortars were moved to the

[Page 117]

front, and his guns trained on Wagner. A powerful calcium

light was arranged to illumine the enemy's work, that our fire might

be continuous and effective. Changes were also made in the

regiments furnishing permanent details in the trenches and advanced

works, and an important part, requiring courage and constancy, was

now assigned to our regiment. It is indicated in the following

order: —

HEADQUARTERS U. S. FORCES,

MORRIS ISLAND,

S. C, Aug. 31, 1863.

Special Orders No. 131.

II. The Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteers, Col. M.

S. Littlefield, Fourth South Carolina Volunteers, commanding, are

hereby detailed for special duty in the trenches under the direction

of Maj. T. B. Brooks, A. D. C. and Assistant Engineer.

The whole of the available force of the regiment will be divided

into four equal reliefs, which will relieve each other at intervals

of eight hours each. The first relief will report to Major

Brooks at the second parallel at 8 a. m. this day. No

other details will be made from the regiment until further orders.

By order of

BRIG.-GEN. A. H. TERRY.

ADRIAN TERRY,

Captain, and Assistant Adjutant-General.

Major Brooks, in his journal

of the siege under date of August 31, thus writes, —

"The Third United States Colored Troops, who have been on fatigue

duty in the advance trenches since the 20th inst., were relieved

to-day by the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Volunteers (colored), it

being desirable to have older troops for the important and hazardous

duty required at this period." Throughout the whole siege the

First New York Engineers held the post of honor. Their sapping

brigades took

[Page 118]

the lead in the advance trench opening the ground, followed by

fatigue details which widened the cut and threw up the enlarged

cover. These workers were without arms, but were supported by

the guard of the trenches. Upon this fatigue work with the

engineers, the Fifty-fourth at once engaged. During the night

of the 31st work went on rapidly, as the enemy fired but little.

Out of a detail of forty men from the One Hundred and Fourth

Pennsylvania, one was killed and six were wounded. One of the

guard was killed by a torpedo. A man of Company K, of our

regiment, was mortally wounded that night.

Early on September 1 our land batteries opened on

Sumter, and the monitors on Wagner. Four arches in the north

face of Sumter with platforms and guns were carried away.

Lieut. P. S. Michie, United States Engineers, was temporarily in

charge of the advance works on the right. Much work was done

in strengthening the parapets and revetting the slopes. Our

Fifty-fourth detail went out under Lieutenant Higginson that

morning, and had one man wounded. Rev. Samuel Harrison,

of Pittsfield, Mass., commissioned chaplain of the regiment, arrived

that day.

September 2 the land batteries were throwing some few

shots at Sumter and more at Wagner. Capt. Jos. Walker,

First New York Engineers, started the sap at 7 p. m. in a new

direction under heavy fire. Considering that the trench was

but eighty yards from Wagner, good progress was made. The

sap-roller could not be used, because of torpedoes planted

thereabout. Our fire was concentrated upon Wagner on the 3d,

to protect sapping. But little success resulted, for the

enemy's sharpshooters on the left enfiladed our trench at from one

hundred to three hundred yards. At this time the narrowest

development in the

[Page 119]

whole approach was encountered, — but twenty-five yards; and the

least depth of sand, — but two feet. Everywhere torpedoes were

found planted, arranged with delicate explosive mechanism.

Arrangements were made to use a calcium light at night. From

August 19 to this date, when the three regiments serving as guards

of the trenches were relieved by fresher troops, their loss

aggregated ten per cent of their whole force, mainly from artillery

fire.

On the night of the 3d, "Wagner fired steadily,

and the James Island batteries now and then. Our detail at the

front had George Vanderpool killed and Alexander

Hunter of the same company — H — wounded. Throughout

the 4th we fired at Wagner, and in the afternoon received its

last shot in daylight. Captain Walker ran the

sap twenty-five feet in the morning before he was compelled to

cease.

When the south end of Morris Island was captured,

Maj. O. S. Sanford, Seventh Connecticut, was placed in charge of

two hundred men to act as "boat infantry." From their camp on

the creek, near the Left Batteries, details from this force were

sent out in boats carrying six oarsmen and six armed men each.

They scoured and patrolled the waters about Morris Island.

Throughout the whole siege of Charleston this boat infantry was kept

up, under various commanders. It was thought that could

Gregg be first taken, Wagner's garrison might be captured

entire; and an attempt to do so was arranged for the night of

September 4. Details for the enterprise, which was to be a

surprise, were made from four regiments under command of Major

Sanford. The admiral was to send boats with howitzers

as support. When all was ready, the boats started toward

Gregg. Nearing that work, several musketshots were heard.

A navy-boat had fired into and cap-

[Page 120]

tured a barge of the enemy with Maj. F. F. Warley, a surgeon,

and ten men. This firing aroused Gregg's garrison; our

boats were discovered and fired upon. Thus the surprise was a

failure, and the attack given up.

Wagner was now in extremis, and the garrison

enduring indescribable misery. A pen picture of the state of

things there is given by a Southerner as follows : —

"Each day, often from early dawn, the 'New Ironsides'

or the monitors, sometimes all together, steamed up and delivered

their terrific fire, shaking the fort to its centre. The

noiseless Cohorn shells, falling vertically, searched out the secret

recesses, almost invariably claiming victims. The burning sun

of a Southern summer, its heat intensified by the reflection of the

white sand, scorched and blistered the unprotected garrison, or the

more welcome rain and storm wet them to the skin. An

intolerable stench from the unearthed dead of the previous conflict,

the carcasses of cavalry horses lying where they fell in the rear,

and barrels of putrid meat thrown out on the beach sickened the

defenders. A large and brilliantly colored fly, attracted by

the feast and unseen before, inflicted wounds more painful though

less dangerous than the shot of the enemy. Water was scarcer

than whiskey. The food, however good when it started for its

destination, by exposure, first, on the wharf in Charleston, then on

the beach at Cumming's Point, being often forty-eight hours in

transitu, was unfit to eat. The unventilated bombproofs,

filled with smoke of lamps and smell of blood, were intolerable, so

that one endured the risk of shot and shell rather than seek their

shelter. The incessant din of its own artillery, as well as

the bursting shell of the foe, prevented sleep. . . ."

General

Beauregard on September 4 ordered Sumter's garrison reduced

to one company of artillery and two of infantry under Maj.

Stephen Elliott. Early on the 5th

[Page 121]

the land batteries, "Ironsides," and two monitors opened a terrific

bombardment on Wagner which lasted forty-two hours. Under its

protection our sap progressed in safety. Wagner dared not show

a man, while the approaches were so close that the more distant

batteries of the enemy feared to injure their own men. Our

working parties moved about freely. Captain Walker

ran some one hundred and fifty yards of sap; and by noon the flag,

planted at the head of the trench to apprise the naval vessels of

our position, was within one hundred yards of the fort. The

Fifty-fourth detail at work there on this day had Corp.

Aaron Spencer of Company A mortally wounded by one of our

own shells, and Private Chas. Van Allen

of the same company killed. Gregg's capture was again

attempted that night by Major Sanford's command.

When the boats approached near, some musket-shots were exchanged;

and as the defenders were alert, we again retired with slight loss.

Daylight dawned upon the last day of Wagner's memorable

siege on September 6. The work was swept by our searching fire

from land and water, before which its traverses were hurled down in

avalanches covering the entrances to magazines and bombproofs.

Gregg was also heavily bombarded. As on the previous day our

sappers worked rapidly and exposed themselves with impunity.

The greatest danger was from our own shells, by which one man was

wounded. Lieutenant McGuire, U. S. A., was in charge a

part of the day. He caused the trenches to be prepared for

holding a large number of troops, with means for easy egress to the

front. Late that evening General Gillmore issued

orders for an assault at nine o'clock the next morning, the hour of

low tide, by three storming columns under General

[Page 122]

Terry, with proper reserves. Artillery fire was to be

kept up until the stormers mounted the parapet. At night the

gallant Captain Walker, who was assisted by Captain Pratt,

Fifty-fifth Massachusetts, observed that the enemy's sharpshooters

fired but scatteringly, and that but one inortar-shell was thrown

from Wagner. About 10 P. M. he passed into the ditch and

examined it thoroughly. He found a fraise of spears and

stakes, of which he pulled up some two hundred. Returning, a flying

sap was run along the crest of the glacis, throwing the earth level,

to enable assailants to pass over readily.

From early morning Col. L. M. Keitt, the

Confederate commander of Morris Island, had been signalling that his

force was terribly reduced, the enemy about to assault, and that to

save the garrison there should be transportation ready by nightfall

of the 6th. He reported his casualties on the 5th as one

hundred out of nine hundred; that a repetition of that day's

bombardment would leave the work a ruin. He had but four

hundred effectives, exclusive of artillerymen. His negro

laborers could not be made to work; and thirty or forty soldiers had

been wounded that day in attempting to repair damages.

General Beauregard, who had been, since the 4th at least,

jeopardizing the safety of the brave garrison, then gave the

necessary order for evacuation.

A picket detail of one hundred men went out from the

Fifty-fourth camp at 5 P.M. on the 6th. Our usual detail was

at work in the front under the engineers. It was not until two

o'clock on the morning of September 7 that the officers and men of

the regiment remaining in camp were aroused, fell into line, and

with the colored brigade marched up over the beach line to a point

just south of the Beacon

[Page 123]

house, where these regiments rested, constituting the reserve of

infantry in the anticipated assault. Many of the regiments were

arriving or in position, and the advance trenches were full of

troops. Soon came the gray of early morning, and with it

rumors that Wagner was evacuated. By and by the rumors were

confirmed, and the glad tidings spread from regiment to regiment .

Up and down through the trenches and the parallels rolled repeated

cheers and shouts of victory. It was a joyous time our

men threw up their hats, dancing in their gladness. Officers

shook hands enthusiastically. Wagner was ours at last.

In accordance with instructions, at dark on the 6th the

Confederate ironclads took position near Sumter. Some

transport vessels were run close in, and forty barges under

Lieutenant Ward, C. S. N., were at Cumming's Point.

A courier reported to Colonel Keitt that everything

was prepared, whereupon his troops were gradually withdrawn, and

embarked after suffering a few casualties in the movement. By

midnight Wagner was deserted by all but Capt. T. A. Huguenin,

a few officers, and thirty-five men. The guns were partially

spiked, and fuses prepared to explode the powder-magazine and burst

the guns. At Gregg the heavy guns and three howitzers were

spiked, and the magazine was to be blown up. The evacuation

was complete at 1.30 A.M. on the 7th. At a signal the fuses

were lighted in both forts; but the expected explosion did not occur

in either work, probably on account of defective matches.

Just after midnight one of the enemy, a young Irishman,

deserted from Wagner and gained our lines. Taken before

Lieut.-Col. O. L. Mann, Thirty-ninth Illinois, general officer

of the trenches, he reported the work abandoned and the enemy

retired to Gregg. Half an hour later all the guns

[Page 124]

were turned upon Wagner for twenty minutes, after which Sergeant

Vermillion, a corporal, and four privates of the Thirty-ninth

Illinois, all volunteers, went out. In a short time they

returned, reporting no one in Wagner and only a few men in a boat

rowing toward Gregg. On the receipt of this news the flag of

the sappers and the regimental color of the. Thirty-ninth

Illinois were both planted on the earthwork. A hasty

examination was made of Wagner, in the course of which a line of

fuse connecting with two magazines was cut. Every precaution was

taken, and guards posted at all dangerous points.

A few moments after our troops first entered Wagner two

companies of the Third New Hampshire under Captain Randlett

were pushed toward Gregg. Capt. C. R. Brayton, Third

Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, and some Fifty-fourth men started for

the same point. Amid the sand-hills the Third New Hampshire

men stopped to take charge of some prisoners, while Captain

Brayton kept on, and was the first to enter Gregg, closely

followed by the Fifty-fourth men. In Wagner eighteen pieces of

ordnance were found, and in Gregg, seven pieces. All about the

former work muskets, boarding-pikes, spears, and boards filled with

spikes were found arranged to repel assaults. Inside and all around,

the stench was nauseating from the buried and unburied bodies of men

and animals. The bombproof was indescribably filthy. One

terribly wounded man was found who lived to tell of his sufferings,

but died on the way to hospital. Everywhere were evidences of

the terrific bombardment beyond the power of pen to describe.

About half a dozen stragglers from the retiring enemy

were taken on the island. Our boats captured two of the enemy's

barges containing a surgeon and fifty-five men,

[Page 125]

and a boat of the ram "Chicora" with an officer and seven sailors.

Wagner's siege lasted fifty-eight days. During

that period 8,395 soldiers' day's work of six hours each had been

done on the approaches; eighteen bomb or splinter proof

service-magazines made, as well as eighty-nine emplace ments for

guns, — a total of 23,500 days' work. In addition, forty-six

thousand sand-bags had been filled, hundreds of gabions and fascines

made, and wharves and landings constructed. Of the nineteen

thousand days' work performed by infantry, the colored troops had

done one half, though numerically they were to white troops as one

to ten. Three quarters of all the work was at night, and nine

tenths under artillery and sharpshooters' fire or both combined.

Regarding colored troops, Major Brooks, Assistant Engi

neer, in his report, says, —

"It is

probable that in no military operations of the war have negro troops

done so large a proportion, and so important and hazardous fatigue

duty, as in the siege operations on the island."

The colored

regiments participating were the Fifty-fourth and Fifty-fifth

Massachusetts, First North Carolina, Second South Carolina, and

Third United States Colored Troops. Officers serving in charge

of the approaches, when called upon by Major Brooks to

report specifically upon the comparative value of white and colored

details under their charge for fatigue duty during the period under

consideration, gave testimony that for perseverance, docility,

steadiness, endurance, and amount of work performed, the blacks more

than equalled their white brothers. Their average of sick was

but 13.97, while that of the whites was 20.10

[Page 126]

The percentage of duty performed by the blacks as compared with the

whites was as fifty-six to forty-one.

Major Brooks further says, —

"Of the

numerous infantry regiments which furnished fatigue parties, the

Fourth New Hampshire did the most and best work, next follow the

blacks, — the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts and Third United States

Colored Troops."

General

Beauregard reports his loss during the siege as a total of

296, exclusive of his captured. But the official "War Records"

show that from July 18 to September 7 the Confederate loss was a

total of 690. The Federal loss during the same period by the

same authority was but 358.

Despite the exposure of the Fifty-fourth details day

and night with more or less officers and men at the front, the

casualties in the regiment during the siege as given by the

Adjutant-General of Massachusetts were but four killed and four

wounded.

Shortly after the fall of Wagner the following order

was issued to the troops.

DEPARTMENT OF THE SOUTH,

MORRIS ISLAND, S. C.,

Sept. 15, 1863.

It is with no

ordinary feelings of gratification and pride that the

brigadier-general commanding is enabled to congratulate this army

upon the signal success which has crowned the enterprise in which it

has been engaged. Fort Sumter is destroyed. The scene

where our country's flag suffered its first dishonor you have made

the theatre of one of its proudest triumphs.

The fort has been in the possession of the enemy for

more than two years, has been his pride and boast, has been

strengthened by every appliance known to military science, and has

defied the assaults of the most powerful fleet the world ever saw.

[Page 127]

Bat it has yielded to your courage and patient labor. Its

walls are now crumbled to ruins, its formidable batteries are

silenced, and though a hostile flag still floats over it, the fort

is a harm less and helpless wreck.

Forts Wagner and Gregg, works rendered memorable by

their protracted resistance and the sacrifice of life they have

cost, have also been wrested from the enemy by your persevering

courage and skill, and the graves of your fallen comrades rescued

from desecration and contumely.

You now hold in undisputed possession the whole of

Morris Island; and the city and harbor of Charleston lie at the

mercy of your artillery from the very spot where the first shot was

fired at your country's flag and the Rebellion itself was

inaugurated.

To you, the officers and soldiers of this command, and

to the gallant navy which has co-operated with you are due the

thanks of your commander and your country. You were called

upon to encounter untold privations and dangers, to undergo

unremitting and exhausting labors, to sustain severe and

disheartening reverses. How nobly your patriotism and zeal

have responded to the call the results of the campaign will show and

your commanding general gratefully bears witness.

Q. A. Gillmore,

Brigadier- General Commanding.

|