|

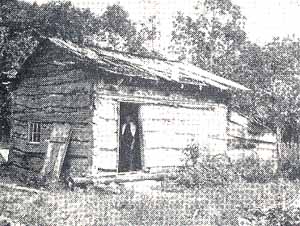

THE humble log cabin of a century ago was a humble

home indeed, yet it surpassed in one respect many a millionaire's

mansion today. Though a single room housed a big family -

sometimes more than one - there was always room for the stranger,

the new settler or the traveler. The genuine hospitality of

the early settler has been the theme of many a story.

The pioneer had little, but that little he generously shared with

one who had less. If necessary, he was willing to give all he

had. It was nothing to travel mile after mile through

bottomless mud and swollen streams to see a sick neighbor. No

distance was too far if some one needed help. When the

newcomer arrived everybody dropped his own affairs and went to

work to "raise" a cabin for him. To have charged a

fee for a night's lodging would have been the height of impropriety

and would not have been tolerated. To have refused to lend a

tool would have aroused the whole neighborhood to resentment.

A man's word was as good as his bond. Implicit confidence in

one another prevailed. No matter what sacrifice was required a

man met any promise he had made. It was considered a

reflection on one's integrity if one were asked to give a note in

promise of payment. FIGHTING COMMON

A man's character was not to be assailed lightly in those days.

The pioneer was quick to resent a real or imaginary wrong.

Slander cases were quit common. A man was always ready for a

fight. Life on the frontier was not only a battle with nature,

but often a battle with fists with the other fellow.

The word "liar" always brought

on a fight. It was a signal to go. Though fighting was a

violation of the law, the authorities winked at it. A justice

of the peace once said: "Boys, if you must fight, fight where

I can't see you. If I see you fighting I will have to arrest

and fine you. But when a fight did occur, it settled

the difficulty. The man who was beaten acknowledged it.

The combatants shook hands and were friends again. No one lay

in a dark alley with a blackjack waiting for his enemy. He

settled the matter in the broad, open light of day, with plenty of

witnesses. A good fight always enlivened any occasion.

A fight was not always the result of a quarrel. If a man had a

reputation for being the "best" man he had to defend that

reputation. Two good men would go out of their way to meet

each other and settle the question as to who was the better man.

Did it matter that a fellow was all bruised up and bleeding when he

got through? No, no! His honor was at stake!

AMUSEMENTS So when his corn and wheat and flax were harvested, he

had little to do but hunt and fish. To vary the entertainment,

there were horse races, shooting matches, deer hunts, fix and wolf

chases, ax throwing exhibitions, jumping and wrestling matches,

dancing, and trials of strength. Ax throwing was somewhat

dangerous, but it proved one's skill. A small area would be

marked on a tree, and the aim of each thrower was to stick the ax

blade inside that area. The horse racing became popular at the

mills, while the men were waiting their turn to have their corn

ground. The racing horses were the common farm stock, and cows

and other animals were wagered on the outcome of the races.

Often "roughhouses" resulted, for whisky was drunk freely.

Some of the earliest mills in Macon county were King's mill on

Stevens creek, Allen's mill on the Sangamon, the Davis mill on Big

Creek, and the Robert Smith and Whitley mills southwest of Decatur.

AN OLD MILL

This picture of the old John Morrison mill on Salt Creek, in Dewitt

county, is typical of mills in early Macon County. In

those days a popular fellow was the man who could play the fiddle.

The fiddle was the only kind of musical instrument to be had, and

the fiddler was always sure of an invitation to every party.

Most of the fiddlers of the early day were unable to play by note,

but they produced the music, and that was all that was necessary.

Being in a position to hear much gossip, the fiddler usually was a

veritable news gatherer - and dispenser also. Singing schools,

house raisings, corn shuckings - any of the occasions that served to

bring the people together - furnished the social life. Keeping the

fireplace supplied with the wood was practically the only work to be

done in the winter time. The fire was never allowed to die out

winter or summer. There were no matches then, and if the fire

died out it was necessary to go to neighbors for live coals to

rekindle it. The pioneer was skilled in the use of the ax.

With it he could build his house, without nails, screws or locks.

Cabins were usually built at the edge of the timber, sites where

water and wood were plentiful being chosen. No one then was so

wild as to dream that some day the prairie would be inhabited.

The most that was claimed was that farms would extend a short

distance out from the timber. Prairie land would be forever

wild and used for grazing purposes only. The prairies were

submerged with water a good part of the year. Horses and

cattle mired on ground that is now the best farming land in the

county. There were no plows suitable to break the tough

prairie sod. At first there were no fences, and animals roamed at

will. When fences did come, they were built to keep the stock

out, instead of keeping it in. This was according to a

decision of the Supreme court, and it was a big drawback to the

farmers. To build and keep in repair the fences needed to

protect his crop, cost the farmer more than the land itself. Money

was so scarce that sometimes a letter lay unclaimed for weeks

because of lack of cash to pay the postage on it. A man could

haul wheat by wagon to Chicago, Springfield or St. Louis and get for

a bushel only half enough to buy a yard of calico.

PLENTY TO EAT One thing the pioneer usually had in plenty, and

that was something to eat. Deer, bear, turkeys, ducks, quail,

squirrels, rabbits, prairie chickens abounded. The river

contained plenty of fish. Each settler had his truck patch,

where he grew corn and other vegetables. Hogs and cattle were

raised. Greens were to be had for the picking. Johnny

cake and corn pone, and mush and milk, added to the pioneer's diet.

Maple sugar and honey were plentiful, and in season there were wild

fruits. One can easily imagine the pioneer's appetite. For

kitchen ware the earliest comers had only vessels called "noggens,"

hollowed out of wood. Some had tin and pewter ware. The

drinking cup usually was a gourd. The Dutch oven, kettle and

frying pan were necessities. Furniture was home made. If an

extra bed were needed, a few poles were quickly secured, and an ax

and an augur were all the implements necessary to fashion them

together properly. Carding and spinning of flax and wool, weaving

it into cloth and then making it into clothes was one of the chief

duties of the women. Every cabin had its spinning wheel and

loom. The women made their own soap with lye made from wood

ashes, and their own starch from wheat bran. THE

"SHAKES" One of the worst hardships of the early settlers was the

annual recurrence of the malaria, a disease which could not be

avoided in this undrained swampy land.1 It was

called by various names, the ague, chills and fever, and the

"Illinois shakes." It spared no one and was intensely severe.

Often entire families would be ill at one time. Many a prospective

settler, after coming to Illinois - lured by glowing accounts of the

land - packed up his belongings and left after one siege of "the

shakes." THE DEEP SNOW There were two memorable

events in the lives of the early citizens of central Illinois, which

became milestones in reckoning dates. The first was the deep

snow in the winter of 1830-31. For years afterwards dates were

mentioned as "before or after the deep snow." Snow began falling

in the early winter and continued for months, each downfall being

succeeded by heavy sleet which formed a crust of ice. Finally

the snow became so deep that tops of fences could not be seen, and

one could drive right over them.2 People were housed up

for weeks, and there was much suffering, though no loss of life.

Many wild animals and game perished, however. Deer, caught in

the snow, could be killed without the aid of guns. Game was

scarce for years afterward. SUDDEN FREEZE Then in

January, 1836, occurred the "sudden freeze," which also caused

intense suffering. The freeze came about 4 o'clock in the

afternoon of a rainy day. Animals out in the field, and

chickens, geese, ducks, were caught in ice, the water freezing about

their feet. Streams and ponds were stretches of ice. It

was so cold that it was said that boiling water thrown into the air

came down as particles of ice. In other parts of the state several

lives were lost during the sudden freeze. People caught out on

the prairie and unable to find shelter froze to death. Dr.

Thomas H. Read of Decatur, on his way to see a patient, almost lost

his life in that way. Another event of interest was the heavy

rainfall in 1835, which resulted in raising the Sangamon higher than

it had ever been know before. The water drained off slowly.

But all these hardships were endured by the pioneers, and they

stayed. They were the ones who made the prairie a fit place to

live, and to them is due the honor and respect and admiration of the

succeeding generations who have reaped the benefits.

----------------------

1 Quinine was found

in the saddlebags of every doctor of the early day. It was

given for "The Shakes". Many years the county had to suffer

from this disease. It did not disappear until the general

system of farm drainage took the water off the prairies. Then

the farmers weren't thinking of waging war against the disease when

they started the drainage systems, but were undertaking it with the

idea of increased production of their farms. It served both

purposes, however. The mosquitoes disappeared, malaria was

known no more, and the farm land was greatly improved.

2 Nathaniel Brown, the first blacksmith in Friend's creek

township, came to Illinois from Tennessee in 1830, just after the

snow fell. He moved into a house he bought, and the man who

sold it told him it was enclosed by a seven-rail fence. The

purchaser was unable to get a sight of that fence until the

following spring, when the snow melted.

<PREVIOUS> <NEXT>

<CLICK

HERE TO RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS>

|