|

IRELAND

EMIGRATION

and

VALUATION AND PURCHASE OF LAND IN IRELAND

By John Locke

LONDON:

John William Parker and Son, 445, West Strand;

or from the author, 14, Henrietta Street, Dublin.

Published 1853

| p. 5 -

Irish Emigration, with especial

reference to the working of the Incumbered Estates

Commission.

-----

[Read before the tatistial Section of

the British Association, at Belfast, 3rd Sept., 1852]

------

| THE agricultural

blight of 1846, which swept away the staple food

of the Irish peasantry, initiated a series of

events, that promise to result in a total

revolution of the social and industrial

condition of Ireland. Not only the love of

country, but the rude agrarian links, that bound

the peasant to his farmstead, at whatever

desperate risk, were completely broken by the

loss of the potato crop; and, following close

upon the steps of famine, came that

emigration,so unprecedented in extent, as to be

termed by journalists the National Exodus;

and which now appears to be annually increasing

beyond the supply from births and immigration,

the circle of attraction being widened by every

emigrant, whose first savings are almost

invariably transmitted to the parent country,

for the purpose of defraying the passage-money

of relatives and friends; the remittances from

North America to Ireland, in 1851, intended

mainly for this purpose, amounting to the

enormous sum of 990,000l.* |

|

Social revolution |

According to the twelfth report of the Colonial

Land and Emigration Commissioners, the total

decrease in the population between 1841 and 1851

was 1,659,330, and the emigration within the

same period 1,289,133, or more than

three-fourths of this decrease. Again, by

the last census, the population of Ireland on

Mar. 31st 1850, was

6,515,794, and, assuming the rate of increase by

births at 1 per cent, per annum, it would give

an annual addition of only 65,157: but the

number of emigrants in 1851 is estimated at

257,372, or about double the average emigration

of the preceding ten years, whilst it exceeds

any probable increase of the population by

nearly four to one; and this disproportion is

still further aggravated by the fact, that the

outflow is of vigorous adults (male and female

in nearly equal numbers), by whom population is

mainly sustained, while orphaned infancy,

destitution, and old age, an unprolific remnant,

are left behind. The attraction of the

gold-fields abroad, and the number of evictions

at home, also contribute largely to swell the

tide of emigration; and both these causes are on

the increase, new gold districts being

discovered, and proprietors of land, especially

those who have purchased under the Encumbered

Estates Court, finding the consolidation of

farms a necessary preliminary to the

introduction of an improved system of

agriculture. This policy is, indeed,

sometimes adopted with as little discretion as

humanity, for tenancy must be considered in most

instances as the indispensable instrumentality

of production and profit, few purchasers being

either willing to farm their land, or competent

to so with advantage. There may be

difficulty in finding a new tenant, but there

can be no mistake

in keeping and encouraging one who is inclined

to improve. |

|

Decrease

of

population |

If then Irish expatriation proceed in this

accelerating ratio (and the number of emigrants

for the first four months of 1852 (76,370)†

-----

* Twelfth Report of the Colonial Land and Emigration

Commissioners, pp. 9 - 12, and p. 68.

† Twelfth Report of the Emigration Commissioners.

p. 6 -

appears to warrant such an inference) a simple

sum in arithmetical progression suffices to

demonstrate, that the country will be denuded of

its agricultural population in a very few years.

There is no doubt, indeed, that the change is

usually a beneficial one for the emigrants

themselves, tending to develop, by many

favourable opportunities, and urgent motives of

action, their moral capabilities, and latent

intellect; and rejecting the servile and

slothful habits of a worn-out state of society

for the awakening energies of a new country,

that affords high remuneration for labour, and

ensures to persevering industry its just measure

of reward. And this observation applies

especially to the inhabitants of the remote

west, where the physical type has been gradually

deteriorating for generations, and the inferior

facial angle, and stunted size, denote

degradation both of the physical and

intellectual man. Where the peasantry had

no knowledge of the wants of an advanced

civilization, and no experience of its comforts,

their food a precarious root, their dwellings of

mud and straw, the result could not be

otherwise; for a sordid habitude of life will

dwarf the bodily frame, and penury will ‘‘chill

the genial current of the soul.” |

|

Increase

of

emigration |

|

An elaborate article was lately published in a

French newspaper (La Presse), by M. Bertillon,

proving by comparison between the former

condition of the negroes and present state of

that emancipated race in the West Indies, that

education and liberty conduce to lengthen life,

and consequently increase population; and had we

time now to enter upon the subject, we might

demonstrate by comparison of Ulster with

Connaught, that the numbers and prosperity of a

population are precisely in proportion to the

extension of sound education, and the

application of the principles of industry and

rational freedom to the conduct of life. |

|

Effects

of

education |

|

We now proceed to consider the reparative

agencies, that promise to check the consequences

of excessive emigration; and these are, 1st, The

general progress of the people, industrial,

educational, and social, 2ndly, A well defined

law of tenure, worked out in the spirit of its

intention by the mutual good-feeling and

good-sense of landlords and tenants; and 3rdly,

The improvement of the labouring classes,

including cottiers and small farmers, whose

profits and wages have been hitherto

insufficient for decent maintenance. Now,

the first mentioned is abundantly manifest in

the decrease of crime and the increase of

agricultural improvement and general enterprise

throughout the country. Of the second, we

may entertain a well-grounded expectation, the

matter being in competent and zealous hands; and

the diminution of poor-law taxation, and

substitution of independent capitalists for

distressed or insolvent landed proprietors, who

were unhappily incapacitated from fulfilling the

responsibilities of their position, afford

strong warranty for the improvement of the

labouring classes; which is, indeed, already

felt in the rise of wages and progress of

industry in all its departments, agricultural,

manufacturing, and commercial. |

|

Reparative

agencies |

|

To discuss all the subjects involved in our

inquiry, would lead to statements and reasonings

quite too numerous and tedious for a brief

essay: I have therefore selected but one branch,

and have now the honour to lay before the

section a series of tables, together with a few

statistical observations, compiled from the

records of the Incumbered Estates Court, proving

the importance and extent of those social and

p. 7

economic changes, which have been facilitated,

rather than caused, by the enactment of a law,

severe indeed in its operation to some, but

justified by the public exigency, and rendered

unavoidable from circumstances that legislative

wisdom could neither anticipate nor control.

The number of Petitions lodged for sale of estates up

to July 3 1st, is 2,389; number of Absolute

Orders for sale, to same date, 1,714; the number

of Conveyances executed to August 9th, is 2,310.

From the first sale under the act, which took place

February 19th 1850, to the end of July 1852, not

quite two years and a half, 779 estates, or

parts of estates, have been sold, in 4,062 lots,

to 2,455 purchasers; so that the number of

proprietors has been more than trebled; and this

proportion is in fact considerably greater; for

the purchases of the Ballinahinch property, and

a few other large estates, are intended for

division and re-sale in lots.

The quantity of land, that has already changed hands,

exceeds 1,000,000 acres, or one-twentieth of the

surface of the island; the total area exclusive

of water amounting, according to the Ordnance

Survey, to 20,177,446 acres.

In comparing the great extent of acreage with the

proportionally small amount of the

purchase-money, especially in the case of

English purchasers (see Table II), it must be

borne in mind, that a great portion of the land,

especially in Mayo and Galway, consists of

mountain, bog, and unreclaimed tracts.

The total proceeds of the sales is upwards of 7,000,000l.,

and the amount distributed up to August 26th,

inclusive of about 1,000,000l. allowed to

incumbrancers, who became purchasers, is

4,248,708l. 11s. 1d., or

nearly two-thirds of the produce of the sales;

thus, not only realizing this enormous amount of

capital, hitherto locked up in barren mortgages

or chancery litigation, but quickening its

circulation, and facilitating its productive

reinvestment in the soil. The comparison

of the number of purchasers with the number of

conveyances executed, and of the amount

distributed with the total amount of sales,

prove how diligently and satisfactorily to the

public the Commissioners are accomplishing their

arduous labours.

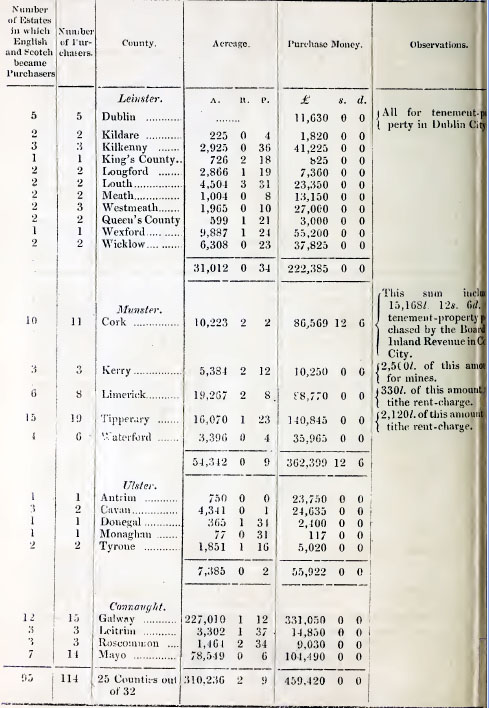

TABLE I.

Showing the Number and

Comparative Amounts of Purchasers under the

Incumbered Estates' Court.

By

this table it appears, that the purchasers

at and under 2000l., are two-thirds

of the whole number; thus exhibiting the

practical tendency of the Act to establish

an independent agricultural middle class,

which is so much wanting in Ireland.

The greatest amount of sales has been in

Galway, - nearly a million; the least in

Londonderry, - only 7015l.

There have been only two purchases exceeding

100,000l., one in Galway, and one in

Queen's County, *

* Emo Park, part of Lord

Portarlington's estate, purchased by

himself; and the Ballinahinch

Etsate in Galway, purchased by the

mortgagees, the Law Life Insurance Company,

who will probably re-sell in lots.

p. 8 -

Showing the County, Acreage, and

Amount - English and Scotch Purchasers.

TABLE II.

Showing the County, Acreage, and Amount -

English and Scotch Purchasers.

p. 9 -

English and Scotch have purchased in every

county in Ireland, except Clare in Muster,

Sligo in Connaught, and Down, Armagh, Cavan,

Fermanagh, and Londonderry, in Ulster.

TABLE III.

Acreage and Amounts arranged according to

Provinces.

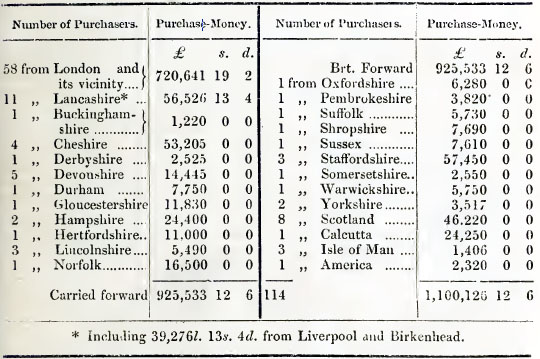

TABLE IV.

Showing the Localities from whence the

Purchase-Money came.

p. 10 -

Of

these, one purchaser was from Calcutta,

amount 24,250l.; three from the Isle

of Man, all under 1,200l.; and eight

from cotland: - viz., one between 2000l.

and 5000l.; and seven between 5000l.

and 10,000l. of the eight purchasers

from Scotland, two were gentry and six

farmers.

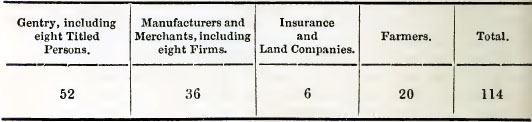

TABLE VI.

Showing (as accurately as can be

ascertained) the Classification of these

Purchasers.

|

|

Incumbered

Estates

Commission. |

It is a fact of great importance, as affecting

the improvement of the far west, that English

and Scotch purchasers, and farmers also, usually

settle in groups. Thus, 63,000 acres of

Sir R. O'Donnell's Mayo estates have been

purchased by English captalists, led by Mr.

Ashworth; whose work, entitled "The Saxon in

Ireland," has been so serviceable to this

country. And now a large portion of Erris,

and of the northern shores of Clew bay, are in

the possession of Englishmen. Again, in

Galway another set of English purchasers,

Messrs, Twining, Ellis, Eastwood, Palmer,

and others, are grouped on the shores of

Ballinakil bay, and in the vale of Kylemore.

Nor are our own countrymen backward in the work

of improvement, nineteen-twentieths of the

purchasers being Irish, and the greater number

of these, especially in the west, diligently

applying their capital to reclamation of the

soil. Even in this prosperous province,*

the advantages of facilitating the sale and

transmission of hopelessly incumbered property,

are remarkably exemplified, the sale of the

Mountcashel estate affording

opportunity to the wealthy citizens of Belfast

to invest their capital in land; and the sale of

the Donegall estate stimulating

the enterprise of manufacturers and tradesmen,

by enabling them to purchase their own holdings

or tenements in the borough.

We now return to our subject of English and Scotch

purchases; and it will be observed, on reference

to the foregoing tables, that by far the greater

proportion of these is in the very districts of

the far west, where the population has been most

diminished, and where capital and improvement

are chiefly required; three-fourths of the total

average being in Galway and Mayo, and two-fifths

of the total amount being invested in the same

counties.

The immigration too is confessedly not of an expulsive

character, abundance of unoccupied land,

perished from stagnant water, or the surface of

which has been only scratched in scattered

patches for centuries, being in the market, and

inviting the advent of more productive systems

of culture.

The number of English and Scotch purchasers, as well as

the

---------------

*Ulsterp. 11 -

amount of their investments, is also increasing.

Up to January 31st of this year, the purchasers

were one-twenty-fifth* as to number, and

one-tenth as to the total amount of

purchase-money. On referring to these

tabbies, we shall find, that up to July 31st the

proportion as to number is one-twentieth, and as

to amount, about one sixth of the total

purchase-money.

It is undeniable, that the forethought, punctuality,

disciplined labour, and scientific skill of the

English and Scotch farmer,—what may in one word

be termed industrial economy, must prove an

invigorating graft on those wayward and

procrastinating habits, that have for so long a

period impeded the improvement of the peasantry

of the south and west of Ireland. |

|

English

immigration |

|

It was not until the jealousies of Norman and

Saxon merged in one common name and undivided

interest, that the signs were developed in

England of that progress, which has placed her

at the head of the nations. And just in

proportion as the invidious distinction of Celt

and Saxon is forgotten in this country, and all

classes, however differing in creed or opinion,

are bound to each other and to the throne by the

links of constitutional loyalty and social

order, will a similar happy example of progress

be developed in Ireland.

_________________________

Observations of the

Valuation and Purchase of Land in Ireland.

[Read before the Statistical Society of

London, 15th November, 1852.]

IN the

present transition state of property in Ireland,

valuation of land, based upon correct data, is

of great importance; and the writer of this

paper respectfully offers the results of his

information and experience on the subject, in

the hope that these may be of service,

especially to English and Scotch capitalists

seeking investments in this country. |

|

Union and

progress. |

|

The Commissioners for the Sale of Incumbered

Estates, in certain cases, direct a special

valuation to be made by some competent valuator,

on application made to them showing proper

reasons for such a measure; but it is required,

in every case, that the Poor Law and Government

valuations should be set forth in the published

rentals of estates for sale |

|

Special

valuations |

| in their court. The

Poor Law valuation may be comparatively useful,

as a check on other valuations, in estimating

the amount of purchase but, having been

originally made, or subsequently revised, by

isolated individuals at different periods,

without co-operation or reference to any fixed

schedule of prices, it cannot be relied on as an

accurate |

|

Poor Law

valuations |

measure of value.

The Government valuations were constituted under

three Acts of Parliament, made respectively in

1839 (6 and 7 Wm. IV. c. 84), 1846 (9 and

10 Vict. c. 110), and 1852 (15 and 16 Vict. c.

63). The first-named, usually termed the

Ordnance Valuation, was based on a fixed scale

of prices of agricultural produce, and intended

to form an uniform and relative valuation, the

townland (the smallest denomination of land

possessing permanent boundaries) being made the

unit

-------------------------

* For more detailed information on this and

other subjects connected with the social

condition of Ireland, the reader is referred to

a pamphlet by the same author, entitled,

"Ireland, Observations on the People, the Land

and the Law,” &c.p. 12 -

p. 13 -

|

|

Government

valuations. |

|

The amount of Poor Law taxation, now happily

dimishing throughout Ireland, will not be a

serious discouragement when it is considered

that the very circumstance of an independent and

employing capitalist becoming the proprietor of

a hitherto insolvent estate, must necessarily

result in the reduction of local taxation. But

purchasers should look closely to the condition

of land as respects drainage, farm buildings, or

excessive population; the expenditure necessary

to remedy imperfections in such matters being,

in reality, an essential element of price. |

|

Poor Law

taxation. |

|

The schedule of prices in the ordnance (or

townland) valuation, and the average for the

first nine months of this year, are here stated,

from comparison of which with the valuation of

any townland, the present annual letting value

can be easily computed. The scale adopted in the

Act last passed is not given, as its utility to

the land market will not be generally available

for several years; the only districts as yet

completed under this Act being the municipal

borough of Cork, four baronies in Kerry, one in

Limerick, and one in Tipperary.† |

|

Comparative

scales of

prices |

-------------------------

* The Ordnance Maps may be had at Hodges and Smith’s,

Dublin, for 2s. 6d., or 5s.

the sheet. The valuations may be inspected

at the office of the General Survey and

Valuation of Ireland, in Dublin. It is

manifest that the townland valuation does not

apply where the lot is only a part of any

townland, but this very seldom occurs.

† Glenarought,

Corkaguiny, Dunkerron North and Dunkerron South,

in Kerry; Iffa and Offa West, in Tipperary; and

Glenquin, in Limerick. |

|

|

p. 14. -

Valuation and Purchases of

Land in Ireland.

TABLE I.

Scale of Prices adopted under the Townland

Valuation, 6 & 7 Wm. IV, c. 84.

TABLE II.

Average of Four Markets - Dublin, Belfast,

Cork, and Mullingar - from

January to September, 1852, both inclusive.

On

comparing these tables it will be seen, at a

glance, that the townland valuation is a

perfectly safe measure of annual value, with the

qualifying observations before started. |

|

|

|

It will

be expected, perhaps, that some definite opinion

should be here given as to the rates of

purchase, but there are so many modifying local

circumstances to be considered in each case,

that any fixed estimate would be incapale

of general application. The published

rentals, when representing the rents previously

to 1846, are in such instances usually

fallacious, and we may therefore refer to the

Government valuations. From 21 to 25

years’ purchase of the net annual value is a

moderate scale in Leinster and Ulster, with

exception of Monaghan and Cavan, where land is

somewhat lower than in the other counties;

finding this net value by deducting the tithe

rent-charge and half the poor rate from the

government valuations,* the full amount of poor

s rate being averaged at 2s. 8d.

in the pound annually. A similar estimate may be

also assumed in Waterford and the eastern half

of Cork. In the remaining counties of

Munster, and in Connaught, from 17 to 22 years*

purchase may be estimated as a safe investment,

finding the net value as before, and the poor

rate being averaged at 5s. in the pound

annually. These are, however, but very

loose approximations. The estate, or lot,

should be personally inspected, and considered

in every aspect, from its geological

-------------------------

* The townland (or ordnance) valuation has been

completed in twenty-six counties, as already

stated. In the remaining six counties the

tenement valuation (where published) may be made

equally available, the results of both being

nearly identical, inasmuch as the scale of the

townland valuation differs very little from the

average prices of 1846, upon which the latter

valuation, or rent-estimate of tenements, has

been founded. |

|

Rates of

purchase |

| p. 15 -

Valuation and Purchases of

Land in Ireland.

structure to its marketable

position. THe capitalist, or farmer,

intending to settle in Ireland, will generally

find estates divided into large farms with

substantial buildings, in Leinster. In

Ulster (excepting Donegal) the rents are

comparatively higher, though quite as well paid

as in Leinster, but the land is much subdivided

throughout all the

manufacturing districts of the former province.

In Munster and Connaught (especially in the

counties of Galway and Mayo) the enterprising

agriculturist will find large tracts in the

market, abundant in all the elements of

undeveloped fertility, inviting the outlay of

capital. |

|

|

| |

|

English and

Irish farming |

| |

|

Purchase of

estates in

Chancery |

| |

|

Of peaty

mountain or

moorland. |

| |

|

Of impropriate

tithe rent

charge |

| |

|

Of head-rents |

Estates subject to heavy head-rents or annuities

have hitherto sold much below the average range

of price brought by unincumbered fee-simple

property; and this circumstance appears to have

mainly influenced the unanimous decision of a

Committee of the House of Lords in recommending

a total abandonment of the claim for the labour-rate

advances made during the famine, and imposed on

our Poor Law unions

in the shape of a consolidated annuity, not

exceeding 40 years. The following communication,

extracted from the report of that Committee,

affords a clear example of the depreciation of

property thus circumstanced, which, however, has

risen in demand with the improvement of our land

market during the past year; as is specially

evidenced by an increased price on re-sales, or

adjourned sales, of from 3 to 7 years

-------------------------

* See “Ireland, Observations on," &c. &c. p. 57.

|

|

Of leaseholds,

and estates

subject to

heavy annual

charges |

| p. 16 -

Valuation and Purchases of

Land in Ireland.

|

|

|

|

INSERT TABLE

-------------------------

|

|

British invest-

ments in the

far west. |

|

p. 17 -

Valuation of Purchase of

Land in Ireland.

But little tenement property has been sold in

Ireland, except in Dublin, Cork and Belfast.

In the last mentioned prosperous community from

25 to 30 years' purchase has been generally give

for the numerous lots of the Marquis of

Donegall's estate: elsewhere such property has

seldom brought more than 18 years; purchase on

the nett rental or value. |

|

Tenement

and house

property. |

| |

|

Freedom from

taxation |

| |

|

Fixed charges

on landed

estates |

| |

|

Incidental

charges |

| |

|

Cheap labour. |

| |

|

Profits on

purchases |

|

|

Warnings to new

proprietors. |

p. 18. -

-------------------------

*See "Ireland, Observations on," &c. &c. pp. 42 - 47. |

|

|

| p. 18 -

Valuation and Purchase of

Land in Ireland.

or accumulations, may reader

himself and succesors in a great measure

independent of those evils that have so deformed

and disorganized our social and civil condition

in Ireland.

The incoming

As the legal |

|

|

|

The neglected tenantry |

|

Neglected

tenantry |

|

Men of capital |

|

Encourage-

ment to

settlers |

| p. 19 -

Valuation and Purchase of

Land in Ireland.

History

affords no parallel

_________________________

The

Schedule of Prices under 15 & 16 Vict. c. 63,

referred to in p. 9, is here added: -

Wheat at the general average of seven shillings and

sixpence per hundred-weight of one hundred and

twelve pounds:

Oats at the general average price of four shillings and

tenpence per hundredweight of one hundred and

twelve pounds;

Barley at the general average price of five shillings

and sixpence per hundredweight of one hundred

and twelve pounds;

Flax at the general average price of forty-nine

shillings per hundred weight of one hundred and

twelve pounds;

Butter at the general average price of sixty-five

shillings and four pence per hundredweight of

one hundred and twelve pounds;

Beef at the general average price of thirty-five

shillings and sixpence per hundredweight of one

hundred and twelve pounds.

Mutton at the general average price of forty-one

shillings per hundredweight of one hundred and

twelve pounds.

Pork at the general average price of thirty-two

shillings per hundredweight of one hundred and

twelve pounds. |

|

|

|

|