|

HE

SCOTTISH NATION;

OR THE

SURNAMES, FAMILIES, LITERATURE, HONOURS,

AND

BIOGRAPHICAL HISTORY

OF THE

PEOPLE OF SCOTLAND

By

WILLIAM ANDERSON,

AUTHOR OF LIFE, AND EDITOR OF WORKS, OF LORD SYROW, &C, &C

44 South Bridge, Edinburgh; and

115 Newgate Street, London.

----

1867

----------

VOLUME III

MACRIMMON, the surname of a minor

sept, (the siol Chrimminn,) who were the hereditary

pipers of Macleod of Macleod. They had a sort

of seminary for the instruction of learners in bagpipe

music, and were the most celebrated bagpipe players in the

Highlands. The first of whom there is any notice was

Ian Odhar, or dun-coloured John, who lived

about 1600. About the middle of the 17th century,

Patrick Mor MacRimmon, having lost seven sons, (he had

eight in all,) within a year, composed for the bagpipe a

touching 'Lament for the children,' called in Gaelic

Cmhadh na Cloinne. In 1745 Macleod's piper,

esteemed the best in Scotland, was called Donald Ban

Macrimmon. When that chief, who was opposed to

Prince Charles, with Munroe of Culcairn, at the head of

700 men, were defeated by Lord Lewis Gordon, and the

Farquharsons, at Inverury, 12 miles from Aberdeen, Donald

Ban was taken prisoner. On this occasion, a

striking mark of respect was paid to him by his brethren of

the bagpipe, which at once obtained his release. The

pipers in Lord Lewis' following did not play the next

morning, as was their wont, and on inquiry as to this

unusual circumstance, it was found by his lordship and his

officers that the pipes were silent because MacRimmon

was a prisoner, when he was immediately set at liberty.

He was, however, shortly afterwards killed in the night

attempt, led by the laird of Macleod, to capture the prince

at Moyhall, the seat of Lady Macintosh near

Inverness.

On the passing of the heritable jurisdiction abolition

bill in 1747, the occupation of the hereditary bagpipers was

gone. Donald Dubh MacRimmon, the

last of them, died in 1822, aged 91. The affecting

lament, Tha til, tha til, tha til, Mhic Chruimin,

"MacRimmon shall never, shall never, shall never

return," was composed on his departure for Canada.

--- Pg. 71 |

MAC

RORY, a surname derived from the name

Roderick called Ruari in the Highlands.

The clan Rory were so styled from Roderick,

the eldest of the three sons of Reginald, second son

of Somerled of the Isles y his second marriage.

This Roderick was lord of Kintyre and one of the most

noted pirates of his day. His descendants became

extinct in the third generation. The clan Donald

and clan Dougall sprung from Roderick's

brothers.

---Pg. 71 |

MONTGOMERY, the

surname of the noble family of Eglinton, which traces its

descent from Roger de Mundegumbrie, Viscount de

Hiesmes, son of Hugh de Mundegumbrie and Joceline de

Beaumont, niece of Gonnora, wife of Richard, duke

of Normandy, great-grandmother of

William the Conqueror. Rogger de Mundegumbrie,

thus nearly allied to the ruling house of Normandy, after

having obtained great distinction under the Norman banner of

France, accompanied his kinsman, William the Conqueror,

into England, and commanded the van of the invading

army at the decisive battle of Hastings in 1066. In

reward of his bravery he was, by the Conqueror, created earl

of Chichester and Arundel, and soon after of Shrewsbury.

He also received from him large grants of land, becoming, in

a short time, lord of no fewer of fifty-seven lordships

throughout England, with extensive possessions in Salop.

Having made a hostile incursion into Wales, he took the

castle of Baldwin, and gave it his own name of Montgomery,

a name which both the town in its vicinity and the entire

county in which it stands have permanently retained.

It is not known whence the name was derived.

Eustace, in his 'Classical Tour,' vol. i, p. 298,

mentions a lofty hill, called Monte Gomero, not far

from Loretto; and in the old ballad of 'Chevy Chase,' the

name is given as Mongon-byrry.

The first of the name in Scotland was Robert de

Montgomery, supposed to have been a grandson of Earl

Roger. When Walter, the son of Alan,

the first high steward of Scotland, whose castle of Oswestry

was in the vicinity of Shrewsbury, came to Scotland to take

possession of several grants of land which had been

conferred upon him by David I., Robert de Montgomery

is a witness to the foundation charter of Walter, the

high steward, to the monastery of Paisley in 1160, and to

other charters between that year and 1175. He died

about 1177.

In the Ragman Roll appear the names of John de

Montgomery, and his brother Murthaw, as among the

barons who swore fealty to Edward I. in 1296.

The former is designated of the county of Lanark, which then

comprehended the county of Renfrew. The latter was the

reputed ancestor of the Montgomeries of Thornton.

Sir John Montgomery, the seventh baron of

Eaglesham, one of the heroes of the battle of Otterburn,

married Elizabeth, only daughter and sole heiress of

Sir Hugh de Eglinton, justiciary of Lothian, and

niece of Robert II., and obtained with her the

baronies of Eglinton and Ardrossan. He was the

ancestor of the earls of eglinton, as mentioned under that

title, where the lineage of that noble family has been

already given, (see vol. ii. page 119).

----------

A baronetcy of

the United Kingdom was possessed by the family of

Montgomery of Macbeth Hill, Peebles-shire descended from

Troilus Montgomery, son of Adam

Montgomery of Giffen, a cadet of the Eglinton family,

living in the reigns of James V., and Mary

queen of Scots. It was conferred, 28th May, 1774, on

William Montgomery of Magbie Hill, but expired on the

death of his son, Sir George Montgomery, second

baronet, 9th July 1831.

Sir William's brother, Sir James Montgomery, of

Stanhope, Peebles-shire, an eminent lawyer, was also created

a baronet. Born at Magbie Hill, in 1721, he was

educated for the Scottish bar, and attained to Considerable

distinction as an advocate. On the abolition of the

heritable jurisdictions in Scotland in 1748, he was one of

the first sheriffs then named by the crown, and he was the

last survivor of those of this first nomination. He

rose gradually to the offices of solicitor-general, and

lord-advocate, and in 1775 was appointed lord-chief baron of

the court of exchequer in Scotland. Upon his

retirement from the bench in 1801, he was created a baronet

of the United Kingdom. His exertions in introducing

the most improved modes of agriculture into Peebles-shire

gained for him the title of 'Father of the county.' He

died Apr. 2, 1803, at the age of 82. his eldest son,

William, lieut.-col. 43d foot, having predeceased

him, he was succeeded by his 2d son, Sir James, 2d

baronet, born Oct. 9, 1766; appointed lord-advocate in1804,

resigned in1806; at one time M. P. for Peebles-shire.

He died May 27, 1839.

His sons by a first wife having predeceased him, he was

succeeded by his eldest son by his 2d wife, daughter of

Thomas Graham, Esq. of Kinross. This son, Sir

Graham Graham Montgomery, 3d baronet, born July 9, 1823,

graduated at Christ Church, Oxford, B. A.; m. in

1845, Alice, daughter of John James Hope-Johnston,

Esq. of Annandale, M. P. Issue 4 sons and 4

drs. Sons: James Gordon Henry, born Feb.

6, 1850, Basil-Templer, Charles Percy, and Arthur

Cecil. M. P. for Peebles-shire, 1852; lord-lieut.

of Kinross-shire, 1854.

Page 183 -

The first of the

family of Montgomerieof Anmuck Lodge, Ayrshire, was

Alexander, second son of Hugh Montgomerie of

Coilsfield, brother of Hugh, twelfth earl of Eglinton.

His son, William Eglinton Montgomerie, succeeded him

in1802. The eldest sister of the latter, Elizabeth,

was the first wife of the Right Hon. David Boyle,

lord-justice-general of Scotland, and died in 1822.

----------

The Irish family

of Montgomery of Grey Abbey, county Down, is

descended from Sir Hugh Montgomery, sixth laird of

Braidstone, in the parish of Beith, Ayrshire, a cadet of the

noble house of Eglinton, and the principal leader in the

colonization of Ulster in 1606. The insurrectionary

disturbances in Ireland before the death of Queen Elizabeth,

had placed a large extent of confiscated property at the

disposal of the crown. The laird of Braidstone, with a

view of obtaining some portion of it, effected the escape of

Con O'Neil, the chief of Ulster, from the castle of

Carrickfergus, where he had long been imprisoned.

O'Neil, in consequence "granted and assigned one half of

all his land estate in Ireland" to him "his heirs and

assigns." Thereafter, O'Neil and Braidstone

went to Westminster, when, through the influence of

Braidstone's brother, George, who was chaplain to

his majesty, O'Neil received pardon of the king;

Braidstone was knighted, and orders were given that the

agreement betwixt them should be confirmed by letters

patent, under the great seal of Ireland, "at such rents as

therein might be expressed, and under condition that the

lands should be planted with British protestants, and that

no grant of fee farm should be made to any person of mere

Irish extraction."

In the winter of 1605, Sir Hugh Montgomery

obtained from O'Neil a deed of feofment of all his

lands. Amongst the gentlemen who joined Sir Hugh

in the enterprize were, John Shaw of Greenock,

Patrick Montgomerie of Blackhouse, Colonel David Boyd,

Patrick Shaw of Kerseland, Hugh Montgomerie,

junior, Thomas Nelvin of Monkreddin, Patrick Mure

of Dugh, Sir William Edmiston of Duntreath, and

Messrs. Neill and Calderwood; besides a great

many retainers. In 1610, only four yeas after the

first planting, Sir Hugh brought before the king's

muster-master 1,000 able fighting men.

The success of his Scotch enterprise led to the

formation of the London companies in 1612, and thus was

founded the protestant province of Ulster, which, says

Hume, from being "the most wild and disorderly province

of all Ireland, soon became the best cultivated and most

civilized.

In 1622, Sir Hugh Montgomery was raised to the

peerage of Ireland as Viscount Montgomery of Ardes,

county Down. He was grandfather of Hugh, third

Viscount Montgomery of Ardes, created in 1661,

earl of Mount Alexander. These titles expired with

Thomas, seventh earl, in 1758.

The Montgomeries of the Hall, county Donegal,

possessing a baronetcy of the united kingdom, of the

creation of 1808, and the Montgomeries of Convoy

House, in the same county, are also descended from the

Eglinton family, their progenitors in Ireland being

among the settlers in Ulster in the reign of James VI

and I.

MONTGOMERY,

ALEXANDER, a celebrated poet of the

reign of James VI., supposed to have been a younger

son of Montgomery of Hazlehead Castle, in Ayrshire, a

branch of the noble family of Eglintoun, was born probably

about the middle of the 16th century. Of his personal

history there are no authentic memorials. In his poem,

entitled 'The Navigatioun,' he calls himself "ane German

born." Dempster describes him as "Equus Montanus,

vulgo vocatus;" but it is certain that he was never

knighted. In the titles to his works he is styled

"Captain," and it is conjectured that he was at one time a

commander in the body guard of the Regent Morton.

Melvil, in his 'Diary,' mentions him about 1577, as "Captain

Montgomery, a good honest man, and the regent's

domestic." His poetical talents procured him the

patronage of James V., from whom he enjoyed a

pension. In his majesty's 'Reulis and Cautelis to be

observit and eschewit in Scottish Poesie,' published in

1584, the royal critic quotes some of Montgomery's

poems, as examples of the different styles of verse.

In his latter years, he seems to have fallen into

misfortunes. His pension was withheld from him.

He was also involved in a tedious law-suit before the court

of session, and he was for some time the tenant of a gaol.

One of his minor pieces is entitled 'The Poet's Complaynte

against the Unkindnes of his Companions, when he wes in

Prissone.' His best known production is his

allegorical poem of 'The Cherrie and the Slae,' on which

Ramsey formed the model of his 'Vision,' and to one

particular passage in which he was indebted for his

description of the Genius of Caledonia. It was first

published in 1595, and reprinted in 1597, by Robert

Waldegrave, "according to a copie corrected by the

author himselfe." Another of his compositions is

styled 'The Flyting betwixt Montgomrie and Polwart.'

He also write 'The Minde's Melodie,' consisting of

Paraphrases of the Psalms, two of which were printed by

Ramsay in his Evergreen. Foulis of Glasgow

published, in 1751, an edition of his poetry, and Urie

of the same place brought another in1754. He composed

a great variety of Sonnets in the Scottish language; and

among the books present by Drummond to the university of

Edinburgh is a manuscript collection of the poems of

Montgomery, consisting of Odes, Sonnets, Psalms, and

Epitaphs. His death appears to have taken place

between 1597 and 1615, in which latter year an edition of

his 'Cherrie and Slae' was printed by Andrew

Page 184 -

Hart. In 1822 a complete edition of his poems

was published at Edinburgh, under the superintendence of

Mr. David Laing, with a biographical preface by Dr.

Irving.

MONTGOMERY, JAMES, an eminent

religious poet, was born in Irvine, in Ayrshire, Nov. 4,

1771. His father, the Rev. John Montgomery, of

Irish birth though of Scottish extraction, was a preacher in

the church of the United or Moravian brethren. When

the poet was about four years and a half old, his parents

returned to their native parish in the county of Antrim, in

the north of Ireland. About two years afterwards he

was sent to the seminary of the United Brethren at Fulneck,

near Leeds, for his education, and he remained there for ten

years. In 1783, his parents went to preach the gospel

among the slaves in the West Indies, where they both died,

his mother at Tobago in 1790, and his father at Barbadoes in

1791.

He was early inspired with a desire to write poetry by

hearing a portion of Blair's 'Grave' read. When

only ten years old, the bent of his mind was shown by his

composition of various little hymns. About 15 he began

to write a heroic poem on the subject of Alfred.' He was

first placed as an assistant in a general dealer's shop, at

Mirfield near Fulneck, but anxious for a higher occupation,

he one day set off, with three shillings and sixpence in his

pocket, to walk to London. He was at a little public

house at Wentworth, when a youth of the name of Hunt,

entered and getting into conversation with him, informed him

that his father, who kept a general store at Wath, in a

neighbouring village, required an assistant. He

accordingly applied, and was successful. The following

year (1790) he obtained an introduction to Mr. Harrison

a London publisher, and having offered him a manuscript

volume of his verses, the latter took him into his shop as

an assistant, although he declined to publish his poems.

In two years more, namely in 1792, he was fortunate enough

to obtain a situation in the establishment of Mr. Gales,

a bookseller of Sheffield, who had set up a newspaper called

the Sheffield Register. In a short time his

employer had to leave England, to avoid imprisonment for

printing articles too liberal for the then government, and

Montgomery at the age of twenty-two, became the

editor and publisher of the paper, the name of which, on its

becoming his part property, he changed to the more poetical

one of The Sheffield Iris.

At that period, the government,

apprehensive of the diffusion in England of the democratic

and republican principles of the first French revolution,

watched with a jealous eye the freedom of the press.

In January 1794, amidst the keen political excitement that

prevailed, Montgomery was prosecuted by the Attorney

General on a charge of having reprinted and sold to a street

hawker, six quires of a ballad, written by a clergyman of

Belfast, commemorating 'The fall of the Bastile' in 1789,

which by the crown was interpreted into a seditious libel.

Being found guilty, notwithstanding the innocence of his

intentions, he was sentenced to three months imprisonment,

in the castle of York, and to pay a fine of £20. In

the following January he was again tried, for a second

imputed political offence, the publication in his paper of a

paragraph which reflected on the conduct of a magistrate in

quelling riot at Sheffield. He was again

convicted, and sentenced to six months' imprisonment in York

castle, to pay a fine of £30, and to give security to keep

the peace for two years. "All the persons," said

Montgomery, writing in 1825, "who were actively concerned in

the prosecutions against me in 1794 and 1795, are dead, and,

without exception, they died in peace with me. I

believe I am quite correct in saying that from each of them

distinctly, in the sequel, I received tokens of good will,

and from several of them substantial proofs of kindness.

I mention not this as a plea in extenuation of offences for

which I bore the penalty of the law; I rest my

justification, in these cases, now on the same grounds, and

no other, on which I rested my justification then. I

mention the circumstance to the honour of the deceased and

as an evidence that, amidst all the violence of that

distracted time, a better spirit was not extinct, but

finally prevailed, and by his healing influence did indeed

comfort those who had been conscientious sufferers."

After his release, his health having been affected by

the confinement, he went for a few weeks to Scarborough, and

then resumed his duties as editor of the Iris.

The proprietorship of

Page 185 -

that paper up to July 3d, 1795, had been a co-partner

between the poet, and Benjamin Naylor but at that

date the partnership was dissolved. Montgomery,

who thence became sole proprietor, giving an engagement for

the payment of £1,600, the sum originally paid for the

property; and although he considered the terms somewhat

hard, a few years of industry and prosperity enabled him to

liquidate the bond. To the columns of his paper he had

contributed occasional pieces of poetry, as well as written

for it a series of Essays, of an entertaining or satirical

nature, entitled 'The Enthusiast.' Between 1790 and

1796 he had written a novel in four volumes, which was never

printed, and was ultimately committed to the flames.

He had also composed various hymns, both political and

religious, and written four addresses, which were spoken at

the theatre at Sheffield. At the beginning of 1797, he

published his first work, entitled 'Prison Amusements, by

Paul Positive,' a name which he early adopted for his

juvenile pieces, and the initials of which were often

mistaken for those of Peter Pindar the celebrated

satirist of the day. The volume contained twenty-four

poems, many of which, as the Preface states, were composed

in bitter moments, amid the horrors of a gaol, under the

pressure of sickness. One of the most conspicuous

pieces in the volume was entitled the 'Pleasures of

Imprisonment.' It was afterwards corrected and greatly

abridged by the author. The largest and most elaborate

piece, however, was "The Bramin,' in two cantos, and in

heroic verse. The same year he commenced a new series

of Essays, in the columns of the Iris, under the

designation of 'The Whisperer, or Hints and Speculations by

Gabriel Silvertongue, Gent.' These incubrations

were, the following year, collected by the author, and

published in a volume at London. He afterwards got

ashamed of the work, and did all he could to suppress it.

In 1801, with the view of extending his poetical

claims, he transcribed three of his poems, from the columns,

he transcribed three of his poems, from the columns of the

Iris, and with the signature of Alcęus,

sent them to the editor of the Poetical Register.'

These were the 'Remonstrance to Winter,' 'The Lyre,' in

blank verse, and 'The Battle of Alexandria.' In the

following year he also contributed some pieces to the same

publication, and on both occasions his poems were highly

eulogised by Dr. Aikin, in noticing that work in the

'Annual Review,' and quotations given. From this

period till 1806, he wrote and inserted in the columns of

the Iris many of the best of his minor pieces, such

as 'The Pillow;' 'The Thunder Storm;' 'The Joy of Grief;'

The Snowdrop;' 'The Ocean;' 'The Grave;' 'The Common Lot,'

&c. In that year appeared 'The Wanderer of

Switzerland, and other Poems,' among which were the pieces

named and others. On its publication, it was at once

acknowledged that a new poet had arisen whose claims to have

his name inscribed on the bard-roll of his country could not

be disputed. The work was most favourably received,

and in the course of a few weeks very copy of the first

edition was sold. A second edition was also speedily

exhausted. A third edition of a thousand copies was

issued by Messrs. Longman and Co., the eminent

London publishers, who had entered into an arrangement with

the author for the purpose. Among other periodicals

which welcomed Mr. Montgomery's work with high and

discriminating praise, was the 'Eclectic Review,' then

conducted by Mr. David Parken, a barrister.

This gentleman soon entered into a correspondence with the

poet, which led to his becoming one of the regular

contributors to that publication, when he had for his

associates such men as Robert Hall, Adam Clarke, Olinthus

Gregory, and John Foster.

On the appearance in 1807, of the third edition of 'The

Wanderer of Switzerland,' the Edinburgh Review opened

its batteries upon it, and in a most abusive critique

predicted "that in less than three years nobody would know

the name of the 'Wanderer of Switzerland,' or any of the

other poems in the collection." As in the memorable

case of Lord Byron, however, the judgment of the

public reversed the decision of the critic. Within

eighteen months, a fourth edition of 1,500 copies of the

condemned volume was passing through the press where the

Edinburgh Review itself was printed, and fifteen years

afterwards, namely in January 1822, it had reached its ninth

edition At that period Montgomery acknowledged

that so great had been the success of the work that it had

Page 186 -

produced him upwards of £800, and more than twelve thousand

copies had been sold, besides about a score of editions

printed in America.

In Byron's 'English Bards and Scotch Reviewers,'

published in 1809, Montgomery found himself noticed

in this strain:

"With broken lyre and cheek serenely pale,

Lo! sad Alcaeus wanders down the vale!

Though fair they rose, and might have

bloomed at last,

His hopes have perished by the northern

blast:

Nipped in the bud by Caledonian gales,

His blossoms wither as the blast prevails!

O'er his lost works let classic

Sheffield weep;

May no rude hand disturb their early

sleep!"

And in a note he

adds, "Poor Montgomery though praised by every

English Review, has been bitterlly reviled by the Edinburgh!

After all, the Bard of Sheffield is a man of considerable

genius; his 'Wanderer of Switzerland' is worth a thousand

'Lyrical Ballads,' and at least fifty 'Degraded Epics.' "

Mr. Montgomery's next work was "The West

Indies,' a poem in four parts and in the heroic couplet,

written in honour of the abolition of the African

slave-trade by the British legislature in 1807. It was

produced at the request of Mr. Bowyer, the London

publisher, to accompany a series of engravings representing

the past sufferings and the anticipated blessings of the

long-wronged Africans, both in their own land and in the

West Indies, and appeared in 1809 in connection with poems

on the same subject, by James Grahame author of 'The

Sabbath,' and Miss Benger. When Montgomery's

poem was republished by itself, accompanied by about

twenty occasional poems, upwards of ten thousand copies were

sold in ten years. His parents had laid down their

lives in behalf of the enslaved and perishing Negro, and in

this poem, their son, with a vigour and freedom of

description and a power of pathetic painting entirely his

own, raised his generous appeal to public justice in the

negro's behalf, which, no doubt, had its effect when, twenty

years after, slavery itself was abolished in all the

colonies belonging to Britain.

In the spring of 1813, Mr. Montgomery published

'The World before the Flood,' a poem in ten cantos in the

heroic couplet, suggested to the poet by a passage in the

eleventh book of Paradise Lost referring to the translation

of Enoch. He had now begun to take an active and

prominent part in the religious and benevolent meetings of

Sheffield and its neighbourhood, particularly in connexion

with missionary movements, the Bible Society, and the

Sabbath School Union, and in 1814 he was regularly admitted

a member of the Moravian church, of which his brother, the

Rev. Ignatius Montgomery, was a minister. He

himself had been intended for the ministry in connexion with

the United Brethren, had not his early tendency to poetry

prevented his entering upon the studies necessary for it.

Another of his brothers, Robert Montgomery, was a

grocer at Woolwich. They were all three educated at

the Moravian seminary at Fulneck. While the poet was

there, the institution was on one occasion visited by no

less a personage than Lord Monboddo the celebrated

Scottish judge. None of the boys had ever seen a lord

before, and Monboddo was a very strange-looking lord

indeed. He wore a large, stiff, bushy periwig,

surmounted by a huge, odd-looking hat; his very plain coat

was studded with broad brass buttons, and his breeches were

of leather. He stood in the schoolroom, with his grave

absent face bent downwards, drawing and redrawing his whip

along the floor, as the Moravian teacher pointed out to his

notice boy after boy. "And this," said the Moravian,

coming at length to young Montgomery, "is a

countryman of your lordship's." His lordship raised

himself up, looked hard at the little fellow, and then

shaking his huge whip over his head, "Ah," he exclaimed, "I

hope his country will have no reason to be ashamed of him."

"The circumstance," said the poet, "made a deep impression

on my mind, and I determined, - I trust the resolution was

not made in vain, - I determined in that moment that my

country should not have reason to be ashamed of me."

In January 1817 a volume was published, entitled 'The

State Lottery, a Dream,' by Samuel Roberts, a friend

of Montgomery, directed against that species of

national gambling, which, too long authorized by government,

was some years after put an end to by act of parliament.

The book

Page 187 -

contained 'Thoughts on Wheels, a poem in five parts,' by

James Montgomery, in which he introduced an 'Ode to

Britain,' written in a lofty strain of patriotism, which was

included in the first edition of the poet's collected poems

in 1836, and a quarter of a century after its first

publication he recited of a century after its first

publication he recited it at a public breakfast given to him

at Glasgow, when he visited Scotland in 1841.

In 1819 he produced 'Greenland and other Poems.'

The principal piece is in five cantos, and contains a sketch

of the ancient Moravian church, its revival in the 18th

century, and the origin of the missions by that people to

Greenland in 1733. The poem as published is only a

part of the author's original plan. It consists of a

series of episodes, some of which are very beautiful, while

the glowing descriptions of the peculiar natural phenomena

of the arctic regions are striking and original. In

1822 appeared his little volume of 'Songs of Zion,' being

imitations or paraphrases of the Psalms of David. In

the following year he was elected vice-president of the

Sheffield Literary and Philosophical Society, then newly

formed, when he delivered the opening lecture; "thus," says

his biographers, "presenting himself for the first time in

that interesting character which he was destined so often

afterwards to sustain, not only before his own townspeople,

but in various other places." In this address,

speaking of the literature of some of the celebrated nations

of antiquity, whose political vicissitudes fill so large a

space in the page of history, he made this striking remark:

"There is not in existence a line of Verse by Chaldęan,

Babylonian, Assyrian, Egyptian,

or Phnician bard.

"They had no poet, and they died."

In December of the

same year, he delivered a 'Lecture on Modern English

Literature' before the same Society. It is comprised

in the series afterwards published.

In 1824, a request having been made to him by his

publishers, Messrs. Longman and Co., to supply them

with as much matter in prose as would make two volumes,

appeared anonymously his 'Prose by a Poet.' Some of

the most interesting portions of this work had been

reconstructed out of the best written of his newspaper

articles, and for a time it sold well, but did not long

retain its popularity. Montgomery himself

remarked that 'Prose by a Poet' would probably fail to

please either of two large classes of readers, namely,

persons of taste merely, who would be disgusted with the

introduction of religious sentiments; and individuals of a

decidedly religious character, who would consider much of

the matter too light or sentimental; and he was not

mistaken. The same year was published a volume

entitled 'The Chimney Sweeper's Friend, and Climbing Boys'

Album,' containing pieces by different authors, 'arranged by

James Montgomery,' and dedicated to the king,

George IV. The work was got up, mainly by

Montgomery's exertions, to aid in effecting the

abolition, at length happily accomplished, of the cruel and

unnatural practice of employing boys in sweeping chimneys.

In 1825 his connexion with the Iris terminated,

as he that year disposed of the newspaper and his printing

business and materials to Mr. John Blackwell, who had

been at one time a Methodist preacher, but afterwards became

a dealer in old books, and was then a printer and stationer.

On his retirement from the paper, which he had conducted for

thirty years, every class of politicians in the town of

Sheffield united in giving him a public dinner, Lord

Milton, afterwards Earl Fitzwilliam in the chair,

as a testimony that there was among them but one feeling of

goodwill towards him, and but one opinion as to the

integrity with which he had for so long a time discharged

his duties as an editor. The dinner took place on the

poet's birthday, November 4th, 1825, when 116 gentlemen sat

down to the table. In returning thanks, the poet

entered into some details relative to his early life, as

well before as after his residence in Sheffield; alluding

also to his varied labours and ultimate success as a poet,

in which character his name will be known to all time.

He spoke with pardonable pride of the success which had

crowned his labours as an author, 'Not indeed," he said,

"with fame and fortune, as these were lavished on my greater

contemporaries, in comparison with whose magnificent

possessions on the British Parnassus my small plot of ground

is no more than Naboth's vineyard to Ahab's

kingdom, but it is my own; it is no

Page 188 -

copyhold; I borrowed it, I leased it from none. Every

foot of it I enclosed from the common myself; and I can say

that not an inch which I had once gained have I ever lost."

Some of his friends who could not attend, including many

ladies, afterwards presented him with 200 guineas, to be

applied to the revival of a mission which his father, the

Rev. John Montgomery, had begun in Tobago, but which had

been suspended since his death in 1791. The proprietor

of the estate on which it as situated, Mr. Hamilton,

a Scotchman, had in his will bequeathed £1000, contingent on

the renewal of the mission. To this sum, the two

hundred guineas were to be added, and the gift was

accompanied by the delicate request that the renewed mission

should be distinguished by the name of Montgomery, in

honour of himself and his father.

At the close of 1825 appeared 'The Christian Psalmodist;

or Hymns, Selected and Original.' These compositions,

562 in number, are from a great variety of authors,

including one hundred from his own pen, which form

part fifth of the collection. The compilation was made

for Mr Collins, the Glasgow publisher (who died Jan.

2, 1853) and for it he received one hundred guineas.

The prefatory essay contains some judicious remarks on the

writing of hymns, as one branch of the poetic art, and one

the works of Bishop Kenn, Dr. Isaac Watts, Addison,

Toplady, Charles Wesley, and others who have excelled in

it. Montgomery also wrote an Introductory essay

to an edition of Cowper's poems, then about to be

issued by Messrs. Chalmers and Collins.

In 1827, appeared 'The Pelican

Island,' by Mr. Montgomery, a poem in blank verse,

suggested by a passage in Captain Flinders' 'Voyage

to Terra Austrailis,' describing the existence of the

ancient haunts of the pelican in the small islands on the

coast of New Holland. The narrative is supposed to be

delivered by an imaginary being who witnesses the series of

events related after the whole has happened. To the

'Pelican Island' was added, as usual, some of his smaller

poems. Previous to its publication a work called 'The

Christian Poet' was issued by Mr. Collins of Glasgow,

with an admirable introductory essay by Mr. Montgomery,

a species of writing in which he excelled. He also

wrote the Introductory Essays to new editions of 'The

Pilgrim's Progress,' 'The Olney Hymns,' the 'Life of the

Rev. David Brainerd,' and other works published by the

same firm. In 1830 he contributed to the Cabinet

Cyclopedia the brief memoirs of Dante, Ariosto,

and Tasso, which appeared in the series of 'Literary

and Scientific Men of Italy.' The same year he

compiled for the London Missionary Society, 'The Missionary

Journal,' from a vast mass of valuable materials which had

been placed in his hands, for which he received £200.

He also delivered a course of lectures on the History of

English Literature before the members of the Royal

Institution of Great Britain at London. The following

years he lectured on Poetry at the same Institution.

Both courses he prepared for the press and published

in 1833.

In 1841 he visited Scotland, for the first and only

time since his childhood. On this occasion he

accompanied the Rev. Mr. Latrobe. Their main

object was the promotion of the missions of the United

Brethren, but Montgomery had also a great desire to

see the land of his birth. "Scotland." he said, in a

letter written in July 1844, to the committee of the Burns'

Festival, "took such early and effectual root in the soil of

my heart that to this hour it appears as green and

flourishing, in the only eyes with which I can now behold

it, as when, after an absence of more than threescore years,

I was favoured to see it with the eyes that are looking on

this paper. Though scarcely four and a half years old

when removed. I have yet more lively, distinct, and

delightful recollections of little Irvine, its bridges, its

river, its street aspect, and its rural landscape, with

sea-glimpses between, then I have equal reminiscences for

any subsequent period of the same length of time, spent

since then in fairer, wealthier, and more familiar, and

therefore less romantic, England. Yet those fond

recollections of my birth place, and renewals of infant

experience had become, through the vista of retrospect, so

ideal, that when, in the autumn of 1841, for the first time,

I returned to the scenes of my golden age, the humble

realities, though as beautiful as heaven's daylight could

make them in the first week

Page 189 -

of a serene October, I could hardly reconcile with the ideal

of themselves, into which they had been transmuted by

frequent repetition and retouching - every time with a

mellowing stroke - in the process of preserving the identity

of things, 'that were to me more dear and precious,' which

had been so soon and so long removed out of sight, but never

out of mind. I can, however, say that with the brief

acquaintance which on that occasion I made with my country

and my birthplace, and especially with what is the glory and

the blessing of both, the frank, and kind, and gracious

inhabitants, - my brief acquaintance, I was going to say,

with these had more than ever endeared to my better feelings

the land that gave me birth and the blood kindred with whom

I felt myself humbly but honestly allied." In a

postscript he explained that by "blood kindred," he meant

his kinship to all the blood of Scotland, neither less nor

more, pretending to no affinity with the noble house of

Eglinton.

He was received with great enthusiasm by the

magistrates and inhabitants of Irvine. That town

is distinguished as 'the only spot in Scotland where the

United Brethren first found a footing." The house in

which the poet was born is still (1856), standing in Halfway

Street. In his father's time the dwelling-house was

under the same roof with the little chapel in which he

ministered. The latter was afterwards converted into a

weaver's shop. A tablet has been placed on the wall to

remind visitors that that humble dwelling was the birthplace

of the author of 'The World before the Flood.' His

reception in Edinburgh and Glasgow was also most gratifying

to his feelings. In the latter city a public breakfast

was given to him.

A collected edition of his works with autobiographical

and illustrative notes, had been published in 1841, and in

1851 the whole of his works appeared in one volume 8vo.

In 1853 he issued a collection of 'Original Hymus, for

Public Private, and Social Devotion.' In his latter

years he enjoyed a pension of £150.

One of his last public appearances was at the meeting

of the Wesleyan Conference at Sheffield in October, 1852.

He entered leaning heavily on the arm of Dr. Hannah

and was by him conducted to a seat in front of the platform.

A few appropriate words from Dr. Hannah introduced

him to the Conference. The president addressed him in

simple and graceful terms. Then the aged and hoary

poet, somewhat bent and very feeble in body, with the silver

hair shining in flakes as it fell thin upon his temples, or

waved slightly upwards from the side of his head, stepped

forward to the front of the platform, and, raising his hands

in prayer and blessing, pronounced the words - "The Lord

bless and keep you; the Lord make his face to shine upon you

and give you peace." The beautiful and impressive way

in which he uttered the last words of this prayer was said

to have been inexpressibly affecting.

Mr. Montgomery,

who was never married, died at his residence, The Mount,

Sheffield, May 1st, 1854, and was buried at Sheffield.

His portrait is subjoined:

JAMES MONTGOMERY

His

funeral was a public one, and a monument was afterwards

erected to his memory in the town of Sheffield.

'Memoirs of the Life and Writings of James Montgomery,

including Selections from his Correspondence, remains in

prose and verse,

Page 190 -

and Conversations on various subjects; by John Holland

and James Everett; have been published in six volumes

8vo, London, 1854-56.

--- Pp. 184 - 190 |

|

Page 223

MURRAY,

a very common surname in Scotland, the origin of which has

already been explained; see ATHOL, duke of, (vol. i,

p. 164,) and moray, a surname, (page 204 of this

volume). An account of the Murrays of

Tullibardine, the ancestors of the Athol family, is

given under the former head, and those of Bothwell and

Abercairney under the latter.

----------

The

first baronet of the family of Murray of Blackbarony

was Sir Archibald Murray, who was created a baronet

of Nova Scotia, May 15, 1628. He was the son of Sir

John Murray, eldest son of Andrew Murray of

Blackbarony, whose ancestors had been seated at Blackbarony

for five generations prior to 1552. Sir John

was the brother of Sir Gideon Murray,

lord-high-treasurer of Scotland and a lord of session,

father of the first Lord Elibank, (see vol. ii, p.

128) and of Sir William Murray, ancestor of the

Clermont family. Lieutenant-colonel Sir Archibald John

Murray, baronet of Blackbarony, formerly of the Scots

fusilier guards, son of Sir John Murray, baronet of

Blackbarony, by his wife, Anne Digby, of the noble family

of Digby, died, without issue, May 22, 1860. He

was succeeded by his brother, Sir John Digby Murray,

baronet, born in 1798, married, 1st, in 1823, Miss

Susannah Cuthbert, issue one son, John Cuthbert;

2dly, in 1827, Frances, daughter and coheiress of

Peter Patten Bold, Esq., M. p., of Bold hall,

Lancashire; issue, 8 sons and 4 daughters.

----------

The family

of Murray of Clermont, Fifeshire, which possesses a

baronetcy (date 1626), is a branch of the ancient house of

Murray of Blackbarony, whose baronetcy is dated two

yeas later. Sir William Murray, 4th and

youngest son of Sir Andrew Murray of Blackbarony, who

lived in the reign of Mary, queen of Scots, was

knighted by James VI., and having acquired the estate

of Clermont in Fifeshire, it became the designation of his

family. His only son, William Murray of

Clermont, was created a baronet of Nova Scotia, July 1,

1626. Sir James Murray, 5th baronet,

receiver-general of the customs in Scotland, died in

February 1699, without issue, when the title devolved on his

nephew, Sir Robert Murray, 6th baronet, who died in

1771. His eldest son, Sir James Murray, 7th

baronet, a distinguished military officer during the first

American war, was adjutant-general of forces serving on the

continent in 1793. He married in 1794 the countess of

Bath in her own right, and in conse-

Page 224 -

quence assumed the surname and arms of Pulteney.

He subsequently held the office of secretary of war; was

colonel of the 18th foot, and a general in the army.

He died Apr. 26, 1811, leaving no issue, when his

half-brother, Sir John Murray, became 8th baronet.

Sir John was a lieuenant-general in the army, and

colonel of the 56th foot. He died, without issue, in

1827, when the title and estates devolved upon his brother,

the Rev. Sir William Murray, who died May 14, 1842.

The eldest son of the latter, Sir James Pulteney Murray,

10th baronet, died unmarried, Feb. 2, 1843. His

brother, Sir Robert Murray, born Feb. 1, 1815, became

11th baronet; married, in 1839, Susan Catherine Sanders,

widow of Adolphus Cottin Murray, Esq., and 2d

daughter and co-heir of John Murray, Esq., of

Ardeleybury, Herts, lineally descended from Sir William

Murray, father of 1st earl of Tullibardine; with issue,

a son, William Robert, 23d fusiliers, born in 1840,

and a daughter.

----------

The first baronet

of the Stanhope family was Sir William Murray

of Stanhope, and active supporter of the royal cause during

the civil wars, who for his loyalty was created a baronet of

Nova Scotia, after the Restoration, with remainder to his

heirs male whatsoever, 13th February 1664. His

ancestor, John Murray of Falahill, descended from

Archibald de Moravia, mentioned in the Chartulary of

Newbottle in 1280, was known in history as the outlaw

Murray. He died in the early part of the reign of

James V. His exploits are commemorated in

one of the ballads of the 'Minstrelsy of the Scottish

Border.' He married Lady Margaret Hepburn, and

had, with three daughters two sons. His eldest son,

John Murray of Falahill, was ancestor of the Murrays

of Philipbaugh. His second son, William Murray,

married Janet, daughter and heiress of William

Romanno of that ilk, Peebles-shire, and had a son,

William Murray of Romanno, living in December 1531.

The great-grandson of the latter, Sir David Murray,

who was knighted by Charles I., acquired the lands of

Stanhope in the same county, and was the father of Sir

William Murray, the first baronet of Stanhope.

Sir David Murray, the fourth baronet, was implicated in

the rebellion of 1745, and received sentence of death at

York the following year, but was subsequently pardoned on

condition of his leaving the country for life. The

family estates were sold under the authority of the court of

session. Sir David died in exile, without

issue, when the representation of the family devolved on his

uncle, Charles Murray, collector of the customs at

Borrowstownness, who, had the title not been forfeited,

would have been fifth baronet. His son, Sir David

Murray, died without issue at Leghorn, 19th October

1770. The representation of the family then devolved

on John Murray of Broughton, the well-known secretary

of Prince Charles. This personage having

assumed the title after the general act of revisal, became

Sir John Murray of Broughton, baronet. He

married Margaret, daughter of Colonel Robert

Ferguson, brother of William Ferguson of Carloch,

Nithsdale, and had three sons, David, his heir,

Robert, and Thomas, the last a lieutenant-general

in the army. Sir John died 6th December 1777.

His eldest son, Sir David, a naval officer, was

succeeded, on his death in June 1791, by his brother, Sir

Robert, ninth baronet. The son of the latter,

Sir David, became the tenth baronet in 1794, and on his

death, without issue, was succeeded by his brother, Sir

John Murray, eleventh baronet; married, with issue.

----------

The first baronet

of the Ochtertyre family was William Moray of

Ochtertyre, who was created a baronet of Nova Scotia, with

remainder to his heirs male, 7th June 1673. He was

descended from Patrick Moray, the first styled of

Ochtertyre, who died in 1476, a son of Sir David Moray

of Tullibardine. The family continued to spell their

name Moray till 1739, when the present orthography

was adopted by Sir William, 3d baronet. Sir

William Murray, 5th baronet, married Lady Augusta

Mackenzie, youngest daughter of 3d earl of Cromartie;

issue, 3 sons and 2 daughters. He died in 1800.

Of General Sir George Murray, G. C. B., his second

son, a memoir is given at page 232 in

larger type.

The eldest son, Sir Patrick Murray, 6th baronet,

born Feb. 3, 1771, passed advocate at the Scottish bar in

1793, and was appointed a baron of the court of exchequer in

Scotland in 1820. He died June 1, 1837. By his

wife, Lady Mary Hope, youngest daughter of the 2d

earl of Hopetoun, he had 5 sons and 4 daughters.

Capt. John Murray, the 2d son, assumed the name of

Gartshore, on succeeding to the estate of that name in

Dmbartonshire. (See vol. ii, page 284.)

Sir William Keith Murray, the eldest son, 7th

baronet of Ochtertyre, born in 1801, married 1st, Helen

Margaret Oliphant, only child and heiress of Sir

Alexander Keith of Dunnottar, knight marischal of

Scotland; issue, 10 sons and 3 daughters; 2dly, Lady

Adelaide, youngest daughter of 1st marquis of Hastings.

He assumed the name of Keith, on his marriage with

his first wife, and on her death in Oct. 1852, his eldest

son, Patrick, born Jan. 27, 1835, captain grenadier

guards, (retired in June, 1861,) succeeded to the estates of

Dunnottar, Kincardineshire, and Ravelston, Mid Lothian.

Sir William died Oct. 16, 1861, when his eldest son,

Sir Patrick, became 8th baronet.

----------

The Murrays

of Touchadam are supposed to derive from the Morays,

lords of Bothwell. Their progenitor, Sir Willliam

de Moravia, designed of Sanford, joined Robert the

Bruce, but being taken prisoner by the English, was sent

to London in 1306, and remained in captivity there until

exchanged after the battle of Bannockburn. His son and

successor, Sir Andrew de Moravia, called by David

II. "our dear blood relation," obtained from that

monarch a charter of the lands of Kepmad in Stirlingshire,

dated 10th May 1865. This was his first acquisition in

that county. On 28th July 1869 he received another

royal charter of the lands of Tonulcheadam, as

Touchadam was then called, the Tulchmaler, in the same

county. His great-grandson and representative,

William Murray of Touchadam, was scotifer? to

James II., and was appointed constable of Stirling

castle under James III. His eldest son,

David Murray of Touchadam, having no issue, made a

resignation of his whole estate to his nephew, John

Murray of Gawamore, captain of the king's guards and

lord provost of Edinburgh, who succeeded to the same on the

death of his uncle, about 1474. He was a firm and

devoted adherent of James III., and after the battle

of Sauchieburn he was deprived of a considerable portion of

his lands. A great number of the family writs were at

the same time embezzled or lost. His son, William

Murray, the seventh from the founder of the family,

Sir Andrew de Moravia, about 1568, married Agnes,

one of the daughters and coheiresses of James

Cuninghame of Polmaise, Stirlingshire, whereby he

acquired that estate. His son and successor, Sir

John Murray, knight, got a charter under the great seal

of the lands and barony of Polmaise, 8th April 1588.

His grandson, Sir William Murray of Touchadam and

Polmaise, obtained from Charles I. a charter of the

lands of Cowie in 1636. During the civil wars, he

supported the royal cause, and was at the battle of Preston

in 1648, when the army of the royalists under the duke of

Hamilton was defeated. In 1654 he was fined by

Cromwell £1,500.

Page 225 -

William Murray

of Touchadam and Polmaise succeeded his father, William

Murray of Touchadam, Polmaise, and Pitlochie in Fife, in

1814. He died in 1847, when his cousin, John Murray,

born in 1797, the 19th from Sir Andrew de Moravia

succeeded. He died suddenly at London, Apr. 15, 1862,

in his 65th year, and was succeeded by his eldest son,

John, lieutenant-colonel grenadier guards, both in 1831.

----------

The first on

record of the family of Murray of Philiphaugh in

Selkirkshire, Archibald de Moravia, mentioned in the

chartulary of Newbottle in 1280, was also descended, it is

supposed, from the Morays, lords of Bothwell.

In 1296 he swore fealty to Edward I. His son,

Roger de Moravia, obtained in 1321, from James,

Lord Douglas, the superior, a charter of the lands of

Fala, subsequently designated Falahill, for many years the

chief title of the family. The 5th in direct descent

from Roger was John Murray of Falahill, the

celebrated outlaw, who took possession of Ettrick Forest

with 500 men,

"__________ a' in ae liverye

clan.

O' the Lincome grene sae gaye to see;

"He and his ladye in purple clad,

O! gin they lived not royallie!" |

The

king James IV., sent James Boyd to him,

| "The earle of Arran his

brother was he," |

to ask him of whom he

held lands, and desiring him to come and be the king's

"man,"

| "And hald of him yon

fireste free." |

On Boyd

delivering this message to him,

"Thir landis are mine!

the outlaw said;

I ken nae king oin Christentie;

Frae Soudron I this foreste wan.

When the king nor his knightis were not to see." |

And he declared his

intention to keep it

| "Contrair all kingis in

Christentie." |

The king, in

consequence, set forth at the head of a large force,

to punish the outlaw, and force him to submission.

The outlaw summoned to his aid his kinsmen Murray

of Cockpool and Murray of Traquair, who

hastened to Ettrick with all their men. The

barony of Traquair before it came into the

possession of the Stuarts (earls of Traquair)

was the property of the family of Murray,

ancestors of the Murrays of Blackbarony.

The lands of Traquair were forfeited by

Willielmus de Moravia previous to 1464.

They were afterwards, by a charter from the crown

dated 3d February 1478, conveyed to James Stewart,

earl of Buchan, son of the black knight of Lorne,

from whom they descended to the arls of Traquair.

On the approach of the royal force, the outlaw,

"with four in his cumpanie," came and knelt before

the king and said,

"I'll give thee the

keys of my castell,

Wi' the blessing o' my gay ladye,

Gin thou'lt make me sheriffe of this

Foreste,

And a' my offspring after me." |

To this the

king consented, glad to receive his submission

on III.

any terms, and the usual ceremony of feudal

investiture was gone through, by the outlaw

resigning his possessions into the hands of the

king, and receiving them back, to be held of him

as superior.

"He was made

sheriffe of Ettricke Foreste,

Surely while upward grows the tree;

And if he was na traitour to the

king,

Forfaulted he suld never be." |

It is certain

that, by the charter from James IV.,

dated November 30, 1509, John Murray of

Philiphaugh is vested with the dignity of

heritable sheriff of Ettrick Forest, which

included the greater part of what is now

Selkirkshire, an office held by his descendants

till the abolition of the heritable

jurisdictions in 1747. "The tradition of

Ettrick Forest," says Sir Walter Scott,

in his introduction to "The Sang of the Outlaw

Murray,' in the 'Minstrelsy of the Scottish

Border.' "bears that the outlaw was a man of

prodigious strength, possessing a baton or club,

with which he laid lee (i. e. waste) the

country for many miles round, and that he was at

length slain by Buccleuch, or some of his clan,

at a little mount, covered with fir trees,

adjoining to Newark castle, and said to have

been part of the garden. A varying

tradition bears the place of his death to have

been near to the house of the duke of

Buccleuch's gamekeeper, beneath the castle, and

that the fatal arrow was shot by Scott of

Haining from the ruins of a cottage on the

opposite side of the Yarrow. There was

extant, within these twenty years, some verses

of a song on his death. The feud betwixt

the outlaw and the Scotts may serve to

explain the asperity with which the chieftain of

that clan is handled in the ballad." The

laird of Buccleuch had counselled "fire and

sword" against the outlaw; for, says he,

| "He lives by reif

and felonie!" |

But the king

gave him this rebuke:

"And round him

cast a wilie ee, -

Now, haud thy tongue, Sir Walter

Scott,

Nor speak of reif nor felonie: -

For, had every honest man his awin

key,

A right puir clan thy name wad be!" |

The outlaw's

wife, Lady Margaret Hepburn, was the

daughter of the first earl of Bothwell. He

had two sons, James, his heir, and

William, ancestor of the Murrays of

Romanna, afterwards Stanhope, baronets, (see

previous page).

James Murray of Falahill, the elder son, died

about 1529, and his son, Patrick Murray

of Falahill, obtained, under the great seal, a

charter, dated 28th January 1528, of the lands

of Philiphaugh, situated near the royal burgh of

Selkirk, and celebrated as the scene of the

signal defeat of the marquis of Montrose, 15th

September 1645, by General Leslie.

The hollow under the mount adjoining the ruins

of Newark castle, mentioned above as the place

where the outlaw Murray is said to have

been slain, is called by the country people

Slain-man's lee, in which, according to

tradition, the Covenanters, a day or two after

the battle of Philiphaugh, put many of their

prisoners to death. A number of human

bones were, at one period, found there, in

making a drain.

Patrick's great-great-grandson, Sir John

Murray of Philiphaugh, knight, was appointed

by the Scottish Estates one of the judges for

trying those of the counties of Roxburgh and

Selkirk, who had joined the standard of Montrose

in 1646. In 1649 he claimed £12,014, for

the damages he had sustained from Montrose.

He died in 1676.

Page 226 -

His eldest

son, Sir James Murray of Philiphaugh, born in 1655,

was admitted a lord of session in 1689, and appointed

lord-register in 1705. On his death in 1708, he was

succeeded by his eldest son, John Murray of

Philiphaugh, M. P. from 1725 till his decease in 1753.

His gentleman's fourth son, Charles, married a sister

of Robert Scott, Esq. of Danesfield, Bucks, and was

grandfather of Charles Robert Scott Murray, Esq. of

Danesfield, M. P. for that county.

The eldest son, John Murray of Philiphaugh, was

several times M. P. for the county of Selkirk, and once for

the Selkirk burghs, after a severe and expensive contest

with Mr. Dundas. He died in 1800. His

eldest son, John Murray of Philiphaugh, died,

unmarried, in 1830, and was succeeded by his only surviving

brother, James Murray of Philiphaugh, the 17th of the

family, in a direct line; married, with issue.

----------

The Murrays

of Lintrose, Perthshire, are a junior branch of the

Murrays of Ochtertyre, being derived from Mungo

Murray, born 15th July 1662, youngest son of Sir

William Murray of Ochtertyre, baronet, by

Isabel, his wife, the daughter of John Oliphant, Esq.,

of Bachelton. Captain William Murray, a son of

this family, served with the 42d Highlanders, under Wolfe,

in America, and afterwards in the West Indies.

Subsequently, with the rank of major in the same

distinguished regiment, he served under General Howe

against the American revolutionists. On the 15th

September 1776, when the reserve of the British army were in

possession of the heights above New York, Major Murray

was nearly carried off by the enemy, but saved himself by

his strength and presence of mind. Attacked by an

American officer and two soldiers, he kept his assailants at

bay for some time with his fusil; but closing upon him, his

dirk slipped behind him, and being a corpulent man, he was

unable to reach it. Snatching the sword of the

American officer from him, he soon compelled the party to

retreat. He wore the sword as a trophy during the

campaign. He became lieutenant-colonel 27th regiment,

and died the following year.

----------

The Murrays

of Cringletie, Peebles-shire, are descended from a junior

branch of the family of Murray of Blackbarony.

James Wolfe Murray, Esq. of Cringletie, born in 1814,

eldest son of James Wolfe Murray, Lord Cringletie,

a senator of the College of Justice, by Isabella

Katherine, daughter of James Charles Edward Stuart

Strange, Esq., (godson of Prince Charles Edward.)

succeeded his father in 1836; appointed to 42d Royal

highlanders in 1833; married in 1852, Elizabeth Charlotte,

youngest daughter of John Whyte Melville, Esq., and

grand-daughter of 5th duke of Leeds, with issue. His

son, James Wolfe Murray, born in 1853.

----------

Other old

families of the names of Murrays of Broughton,

Wigtownshire; Murray of Murraythwaite, Dumfriesshire;

and Murray of Murrayshall, Perthshire. The

family of Murraythwaite have been settled there since about

1421.

The Murrays of Murrayshall derive in the male

line from the ancient family of Gręme

of Balgowan, and in the female, from that of Murray,

Lord Balvaird, (see vol. i, p. 231,) whose eldest son

succeeded as Viscount Stormont, (see STORMONT, Viscounty

of). John Murray, advocate, son of Andrew

Murray of Murrayshall, at one period sheriff of

Aberdeenshire; born in 1809, succeeded in 1847; m. in

1853, Robina, dr. of Thomas Hamilton, Esq.;

educated at Edinburgh university, M. A. 1828. Passed

advocate in 1831.

The Murrays

of Henderland, Peebles-shire, have given two judges to the

court of session, namely, Alexander Murray, Lord

Henderland, who died in 1795, and his second son, Sir

John Archibald Murray, appointed in 1839, when he

assumed the judicial title of Lord Murray. He

had previously been lord-advocate, and recorder of the great

roll, or clerk of the pipe, in the court of exchequer,

Scotland, a sinecure office which had also been held by his

father, and was resigned by Lord Murray, some time

before first appointment as lord-advocate in 1834. He

was M. P. for the Leith district of burghs from 1832 to

1838. He died in 1859.

MURRAY,

SIR ROBERT, one of the founders and

the first president of the Royal Society of London, was the

son of Sir Robert Murray of Craigie, by a daughter of

George Halket of Pitferran. He is supposed to

have been born about the beginning of the seventeenth

century, and received his education partly at St. Andrews

and partly in France. Early in life he entered the

French army, and became so great a favourite with

Cardinal Richelieu that he soon obtained the rank of

colonel. He returned to Scotland about the time that

Charles I. took refuge with the Scots army; and,

while his majesty was with the latter of Newcastle in

December 1646, he formed a plan for the king's escape, which

was only frustrated by Charles' want of resolution.

"The design, "says Burnet, "proceeded so far that the

king put himself in disguise, and went down the back stairs

with Sir Robert Murray; but his majesty, apprehending

it was scarce possible to pass through all the guards

without being discovered, and judging it highly indecent to

be catched in such a condition, changed his resolution with

Charles II., he was appointed justice-clerk, an

office which appears to have remained vacant since the

deprivation of Sir John Hamilton in 1649. A few

days after he was sworn a privy counciller, and in the

succeeding June was nominated a lord of session, but he

never exercised the functions of a judge. At the

Restoration he was reappointed a lord of session, and also

justice-clerk, and made one of the lords auditors of the

exchequer; but these appointments were merely nominal to

secure his support to the government; for, though he was

properly the first who had the style of lord-justice-clerk,

he was ignorant of the law, and it does not appear that he

ever sat on the bench at all. He was high in favour

with the king, Charles II., by whom he was employed

in his chemical processes, and was, indeed, the conductor of

his laboratory. He was succeeded in the office of

justice clerk in

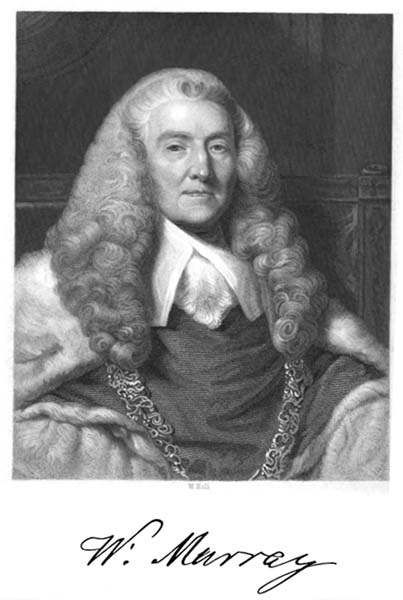

W. MURRAY

Page 227 -

1663 by Sir John Home of Renton; and in 1667 he had a

considerable share in the direction of public affairs in

Scotland, when, not being so obstinately bent on the

establishment of Episcopacy as some of his colleagues, an

unusual degree of moderation marked for a time the

proceedings of the government. Sir Robert's

principal claim to distinction, however, consists in his

having been one of the founders of the Royal Society of

London, and its first president. "While he lived,"

says Bishop Burnet, "he was the life and soul of that

body." He was a member of almost all its obtaining its

charter, in July 1622, and in framing its statutes and

regulations, was indefatigably zealous in promoting its

interests in every respect. Several of is papers,

chiefly on the phenomena of the tides, on the mineral of

Liege, and on other scientific subjects, are inserted

among the early contents of the Philosophical Transactions.

Sir Robert Murray, who had married a sister of

Lord Balcarres, died suddenly, in his pavilion, in the

Garden of Whitehall, July 4, 1673, and was interred at the

king's expense in Westminster Abbey.

MURRAY, THOMAS,

an eminent portrait painter, was born in Scotland in

1666; and at an early age went to London, where he became a

pupil of Riley, state-painter to Charles II., and

successor to Sir Peter Lely He studied nature

carefully, and in his colouring and style imitated his

master, Riley. He painted portraits with great

success and credit; and being employed by the royal family,

as also by many of the nobility, he acquired, in the course

of time, a considerable fortune. The portrait of

Murray, by himself, is honoured with a place in the

gallery of painters at Florence. He died in 1724.

MURRAY, PATRICK, fifth Lord Elibank,

a learned and accomplished nobleman, see ELIBANK,

Lord, VOL. II, P. 130.

MURRAY, WILLIAM,

first earl of Mansfield, a celebrated lawyer and

statesman, the fourth son of David, fifth Viscount

Stormont, was born at Perth, Mar. 2, 1705. He was

removed to London in Mar. 2, 1705. He was removed to

London in 1708, and in 1719 was admitted a king's scholar at

Westminster school. In June 1723 he was entered at

Christ church, Oxford, where he distinguished himself by his

classical attainments. In 1730 he took the degree of

M. A., and afterwards travelled for some time on the

Continent Having become a student at Lincoln's Inn,

he was called to the bar at Michaelmas term 1731. His

abilities were first displayed in appeal cases before the

House of Lords, and he gradually rose to eminence in his

profession. In 1736 he was employed as one of the

counsel for the lord provost and town council of Edinburgh,

to oppose in parliament the Bill of Pains and Penalties,

which afterwards, in a modified form, passed into a law

against them, on account of the Porteous riots. For

his exertions on this occasion, he was presented with the

freedom of the city of Edinburgh in a gold box. In

November 1742 he was appointed solicitor-general in the room

of Sir John Strange, who had resigned. About

the same time he obtained a seat in the House of Commons, as

member for Boroughbridge, in Yorkshire. His eloquence

and legal knowledge soon rendered him very powerful in

debate, and as he was a strenuous defender of the duke of

Newcastle's ministry, he was frequently opposed to Pitt,

afterwards earl of Chatham; these two being considered the

best speakers of their respective parties. In March

1746 he was appointed one of the managers for the

impeachment of Lord Lovat, and the candour and

ability which he displayed on the occasion received the

acknowledgments of the prisoner himself, as well as of the

Lord-chancellor Talbot, who presided on the trial.

In 1754 Mr. Murray succeeded Sir Dudley Ryder

as attorney-general, and on the death of that eminent

lawyer, in November 1756, he became lord-chief-justice of

the king's ben__. Immediately after he was created a

peer of the realm, by the title of Baron Mansfield,

in the county of Nottingham. He was also, at the same

time, sworn a member of the privy council, and, contrary to

general custom, became a member of the cabinet. During

the unsettled state of the ministry in 1757, his lordship

held, for a few months, the office of chancellor of the

exchequer, and during that period he effected a coalition of

parties, which led to the formation of the administration of

his rival Pitt. The same year, on the

retirement of Lord Hardwicke, he declined the offer

of the great seal,

Page 228 -

which he did twice afterwards. During the Rockingham

administration in 1765, Lord Mansfield acted for a

short time with the opposition, especially as regards the

bill for repealing the stamp act. As a judge his

conduct was visited with the severe animadversions of

Junius, and made the subject of much unmerited attack in

both houses of parliament. He was uniformly a friend

to religious toleration, and on various occasions set

himself against vexations prosecutions founded upon

oppressive laws. On the other hand, he incurred much

popular odium by maintaining that, in cases of libel, the

jury were only judges of the fact of publication, and had

nothing to do with the law, as to libel or not. This

was particularly shown in the case of the trial of the

publishers of Junius' letter to the king.

With regard to his thrice refusal of the great seal,

Lord Campbell, in his Lives of the Chief Justices of the

King's Bench, (vol. iii. p. 469,) says, "in 1770, the king

and the duke of Grafton, repeatedly urged Lord Mansfield

to become lord chancellor, but whatever his inclination may

have been when Lord Bute was minister, in the present

ricketty state of affairs he peremptorily refused the

office, and suggested that the great seal should be given to

Charles Yorke, who had been afraid that he would

snatch it from him. By Lord Mansfield's advice

it was that the king sent for Charles Yorke, and

entered into that unfortunate negotiation with him which

terminated so fatally - occasioning the comparison between

this unhappy man, destroyed by gaining his wish, and Semele

perishing by the lightning she had long for. For some

months the chief justice presided on the woolsack as Speaker

of the House of Lords, and exercised almost all the

functions belonging of the office of Lord Chancellor."

In October, 1776, having been

previously created a knight of the Thistle, Lord

Mansfield was advanced to the dignity of an earl of the

United Kingdom by the title of earl of Mansfield, with

remainder to the Stormont family, as he had no issue

of his own. During the famous London riots of June

1780, his house in Bloomsbury Square was attacked and set

fire to by the mob, in consequence of his having voted in

favour of the bill for the relief of the Roman Catholics,

and all his furniture, pictures, books, manuscripts, and

other valuables were entirely consumed. His lordship

himself, it is said, made his escape in disguise, before the

flames burst out. He declined the offer of

compensation from government for the destruction of his

property. The infirmities o_ age compelled him, June

3, 1788, to resign the office of chief-justice, which he had

filled with the distinguished reputation for thirty-two

years. The latter part of his life was spent in

retirement, principally at his seat at Caen Wood, near

Hampstead. He died Mar. 20, 1793, and was buried in

Westminster Abbey. The earldom, which was granted

again by a new patent in July 1792, descended to his nephew,

Viscount Stormont. (See STORMONT,

Viscount of.) A life of Lord Mansfield, by

Holliday, was published in 1797, and another, by

Thomas Roscoe, appeared in 'The Lives of British

Lawyers,' in Lardner's Cyclopędia.

MURRAY, LORD

GEORGE, lieutenant-general of the

rebel Highland army in 1745-6, was the fourth son of the

first duke. Born in 1705, he took a share in the

insurrection of 1715, though then but ten years old, and he

was one of the few persons who joined the Spanish forces

which were defeated in Glenshiel in1719. He afterwards

served several years as an officer in the king of Sardinia's

army; but having obtained a pardon he returned from exile,

and was presented by George I. by his brother the

duke of Athol. He joined Prince Charles at

Perth in September, 1745, and was immediately appointed

lieutenant-general of the insurgent forces. The battle

of Preston, where he commanded the left wing of the prince's

army, was, in a great measure, gained through his personal

intrepidity. "Lord George," says the chevalier

Johnstone, in his 'Memoirs of the Rebellion,' "at the

head of the first line, did not give the enemy time to

recover from their panic. He advanced with such

rapidity that General Cope had hardly time to form

his troops in order of battle when the Highlanders rushed

upon them, sword in hand, and the English cavalry was

instantly thrown into confusion."

On the advance of the rebel army into England, Lord

George had the command of the blockade of Carlisle,

which soon surrendered. Owing to the

Page 229 -

intrigues of Murray of Broughton, secretary to the

prince, whose "unbounded ambition," we are told, "from the

beginning aimed at nothing less than the whole direction and

management of every thing," Lord George was induced,

at this time, to resign his command as one of the

lieutenant-generals of the army, acquainting the prince that

thenceforward he would serve as a volunteer. At the

siege of Carlisle, the duke of Perth had acted as principal

commander, and Lord George, it was thought, was not

willing to serve under him for the rest of the campaign.

The duke, however, subsequently declined the principal

command, when Lord George, who had resumed his place,

became general of the army under the prince.

He was the first to recommend the retrograde movement

from Derby, of which he offered to undertake the conduct.

In that memorable retreat he commanded the rear-guard,

and contrived to keep the English forces effectually in