|

STILL'S

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORDS,

REVISED EDITION.

(Previously Published in 1879 with title: The Underground Railroad)

WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR.

NARRATING

THE HARDSHIPS, HAIRBREADTH ESCAPES AND DEATH STRUGGLES

OF THE

SLAVES

IN THEIR EFFORTS FOR FREEDOM.

TOGETHER WITH

SKETCHES OF SOME OF THE EMINENT FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, AND

MOST LIBERAL AIDERS AND ADVISERS OF THE ROAD

BY

WILLIAM STILL,

For many years connected with the Anti-Slavery Office in

Philadelphia, and Chairman of the Acting

Vigilant Committee of the Philadelphia Branch of the Underground

Rail Road.

Illustrated with 70 Fine Engravings

by Bensell, Schell and Others,

and Portraits from Photographs from Life.

Thou shalt not deliver unto his

master the servant that has escaped from his master unto thee. -

Deut. xxiii 16.

SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION.

PHILADELPHIA:

WILLIAM STILL, PUBLISHER

244 SOUTH TWELFTH STREET.

1886

pp. 23 - 38

[Pg. 23]

SETH CONCKLIN.

IN the long

list of names who have suffered and died in the cause of

freedom, not one, perhaps, could be found whose efforts

to redeem a poor family of slaves were more Christlike

than Seth Concklin's, whose noble and daring

spirit has been so long completely shrouded in mystery.

Except John Brown, it is a question, whether his

rival could be found with respect to boldness,

disinterestedness and willingness to be sacrificed for

the deliverance of the oppressed.

By chance one day he came across a copy of the

Pennsylvania Freeman, containing the story of Peter

Still, "the Kidnapped and the Ransomed," - how

he had been torn away from his mother, when a little boy

six years old; how, for forty years and more, he had

been compelled to serve under the yoke, totally

destitute as to any knowledge of his parents'

whereabouts; how the intense love of liberty and desire

to get back to his mother hand unceasingly absorbed his

mind through all these years of bondage; how, amid the

most appalling discouragements, prompted alone by his

undying determination to be free and be reunited with

those from whom he had been sold away, he contrived to

buy himself; how, by extreme economy, from doing

over-work, he saved up five hundred dollars, the amount

of money required for his ransom, which, with his

freedom, he, from necessity, placed unreservedly in the

confidential keeping of a Jew, named Joseph Friedman,

whom he had known for a long time and could venture to

trust, - how he had further toiled to save up money to

defray his expenses on an expedition in search of his

mother and kindred; how, when this end was accomplished,

with an earnest purpose he took his carpet-bag in his

hand, and his heart throbbing for his old home and

people, he turned his mind very privately towards

Philadelphia, where he hoped, by having notices read in

the colored churches to the effect that "forty-one or

forty-two years before two little boys.*

-------------------------

* Sons of Levin and Sidney - the last

names of his parents he was too young to remember.

[Pg. 24]

were kidnapped and carried South" - that the memory of

some of the older members might recall the

circumstances, and in this way he would be aided in his

ardent efforts to become restored to them.

And, furthermore, Seth Concklin had read now, on

arriving in Philadelphia, after traveling sixteen

hundred miles, that almost the firt man whom Peter

Still sought advice from was his own unknown brother

(whom he had never seen or heard of), who made the

discovery that he was the long-lost boy, whose history

and fate had been enveloped in sadness so long and for

whom his mother had shed been enveloped in sadness so

long, and for whom his mother had shed so many tears and

offered so many prayers, during the long years of their

separation; and, finally, how this self-ransomed and

restored captive, notwithstanding his great success, was

destined to suffer the keenest pangs of sorrow for his

wife and children, whom he had left in Alabama bondage.

Seth Concklin was naturally too singularly

sympathetic and humane not to feel now for Peter,

and especially for his wife and children left in bonds

as bound with them. Hence, as Seth was a

man who seemed wholly insensible to fear, and to know no

other law of humanity and right, than whenever the

claims of the suffering and the wronged appealed to him,

to respond unreservedly, whether those thus injured were

amongst his nearest kin or the greatest strangers, - it

mattered not to what race or clime they might belong, -

he, in the spirit of the good Samaritan, owning all such

as his neighbors, volunteered his services, without pay

or reward, to go and rescue the wife and three children

of Peter Still.

The magnitude of this offer can hardly be appreciated.

It was literally laving his life on the alter of freedom

for the despised and oppressed whom he had never seen,

whose kins-folk even he was not acquainted with.

At this juncture even Peter was not prepared to

accept this proposal. He wanted to secure the

freedom of his wife and children as earnestly as he had

ever desired to see his mother, yet he could not, at

first, hearken to the idea of having them rescued in the

way suggested by Concklin, fearing a failure.

To J. M. McKim and the writer, the bold scheme

for the deliverance of Peter's family was alone

confided. It was never submitted to the Vigilance

Committee, for the reason, that it was not considered a

matter belonging thereto. On first reflection, the

very idea of such an undertaking seemed perfectly

appalling. Frankly was he told of the great

dangers and difficulties to be encountered through

hundreds of miles of slave territory. Seth

was told of those who, in attempting to aid slaves to

escape, had fallen victims to the relentless Slave

Power, and had either lost their lives, or been

incarcerated for long years in penitentiaries, where no

friendly aid could be afforded them; in short, he was

plainly told, that without a very great chance, the

undertaking would cost him his life. The occasion

of this interview and conversation, the seriousness of

Concklin and the utter failure in presenting the

various obstacles to his plan, to create the slightest

apparent misgiving in his mind, or to produce the

slightest sense of fear or

[Pg. 25]

hesitancy, can never be effaced from the memory of the

writer. The plan was, however, allowed to rest for

a time.

In the meanwhile, Peter's mind was continually

vacillating between Alabama, with his wife and children,

and his new-found relatives in the North. Said a

brother, "If you cannot get your family, what will you

do? Will you come North and live with your

relatives?" "I would as soon go out of the world,

as not to go back and do all I can for them," was the

prompt reply of Peter.

The problem of buying them was seriously considered,

but here obstacles quite formidable lay in the way.

Alabama laws utterly denied the right of a slave to buy

himself, much less his wife and children. The

right of slave masters to free their slaves, either by

sale or emancipation, was positively prohibited by law.

With these reflections weighing upon his mind, having

stayed away from his wife as long as he could content

himself to do, he took his carpet-bag in his hand, and

turned his face toward Alabama, to embrace his family in

the prison-house of bondage.

His approach home could only be made stealthily, not

daring to breathe to a living soul, save his own family,

his nominal Jew master, and one other friend - a slave -

where he had been, the prize he had found, on anything

in relation to his travels. To his wife and

children his return was unspeakably joyous. The

situation of his family concerned him with tenfold more

weight than ever before.

As the time drew near to make the offer to his wife's

master to purchase her with his children, his heart

failed him through fear of awakening the ire of

slaveholders against him, as he knew that the law and

public sentiment were alike deadly opposed to the spirit

of freedom in the slave. Indeed, as innocent as a

step in this direction might appear, in those days a man

would have stood about as good a chance for his life in

entering a lair of hungry hyenas, as a slave or free

colored man would, in talking about freedom.

He concluded, therefore, to say nothing about buying.

The plan proposed by Seth Concklin was told to

Vina, his wife; also what he had heard from his

brother about the Underground Rail Road, - how, that

many who could not get their freedom in any other way,

by being aided a little, were daily escaping to Canada.

Although the wife and children had never tasted the

pleasures of freedom for a single hour in their lives,

they hated slavery heartily, and being about to be far

separated from husband and father, they were ready to

assent to any proposition that looked like deliverance.

So Peter proposed to Vina, that she

should give him certain small articles, consisting of a

cape, etc., which he would carry with him as memorials,

and, in case Concklin or any one else should ever

come for her from him, as an unmistakable sign that all

was right, he would send back, by

[Pg. 26]

whoever was to befriend them, the cape, so that she had

the children might not doubt but have faith in the man,

when he gave her the sign, (cape).

Again Peter returned to Philadelphia, and was

now willing to accept the offer of Concklin.

Ere long, the opportunity of an interview was had, and

Peter gave Seth a very full description of

the country and of his family and made known to him,

that he had very carefully gone over with his wife and

children the matter of their freedom. This

interview interested Concklin most deeply.

If his own wife and children had been in bondage,

scarcely could he have manifested greater sympathy for

them.

For the hazardous work before him he was at once

prepared to make a start. True he had two sisters

in Philadelphia for whom he had always cherished the

warmest affection, but he conferred not with them

on this momentous mission. For full well did he

know that it was not in human nature for them to

acquiesce in this perilous undertaking, though one of

these sisters, Mrs. Supplee, was a most faithful

abolitionist.

Having once laid his hand to the plough he was not the

man to look back, - not even to bid his sisters

good-bye, but he actually left them as though he

expected to be home to his dinner as usual. What

had become of him during those many weeks of his

perilous labors in Alabama to rescue this family was to

none a greater mystery than to his sisters. On

leaving home he simply took two or three small articles

in the way of apparel with one hundred dollars to defray

his expenses for a time; this sum he considered ample to

start with. One course he had very safely

concerned about him Vina's cape and one or two

other articles which he was to use for his

identification in meeting her and the children on the

plantation.

He first thought was, on reaching his destination,

after becoming acquainted with the family, being

familiar with Southern manners, to have them all

prepared at a given hour for the starting of the

steamboat for Cincinnati, and to join him at the wharf,

when he would boldly assume the part of a slaveholder,

and the family naturally that of slaves, and in this way

he hoped to reach Cincinnati direct, before their owner

had fairly discovered their escape.

But alas for Southern irregularity, two or three days

delay after being advertised to start, was no uncommon

circumstance with steamers; hence this plan was

abandoned. What this heroic man endured from

severe struggles and unyielding exertions, in traveling

thousands of miles on water and on foot, hungry and

fatigued, rowing his living freight for seven days and

seven nights in a skiff, is hardly to be paralleled in

the annals of the Underground Rail Road.

The following interesting letters penned by the hand of

Concklin convey minutely his last struggles and

characteristically represent the singleness of heart

which impelled him to sacrifice his life for the slave -

[Pg. 27]

EASTPORT, MISS.,

FEB. 3, 1851

TO

WM. STILL:

- Our friends in Cincinnati have failed finding anybody

to assist me on my return. Searching the country

opposite Paducah, I find that the whole country fifty

miles round is inhabited only by Christian wolves.

It is customary, when a strange negro is seen, for any

white man to seize the negro and convey such negro

through and out of the State of Illinois to Paducah,

Ky., and lodge such stranger in Paducah jail, and there

claim such reward as may be offered by the master.

There is no regularity

by the steamboats on the Tennessee River. I was

four days getting to Florence to Paducah.

Sometimes they are four days starting, from the time

appointed, which alone puts to rest the plan for

returning by steamboat. The distance from the

mouth of the river to Florence, is from between three

hundred and five to three hundred and forty-five miles

by the river; by land, two hundred and fifty, or more.

I arrived at the shoe-shop on the plantation, one

o'clock, Tuesday, 28th. William and two

boys were making shoes. I immediately gave the

first signal, anxiously waiting thirty minutes for an

opportunity to give the second and main signal, during

which time I was very sociable. It was rainy and

muddy - my pants were rolled up to the knees. I

was in the character of a man seeking employment in this

country. End of thirty minutes gave the second

signal.

William appeared unmoved; soon sent out the

boys; instantly sociable; Peter and Levin

at the Island; one of the young masters with them; not

safe to undertake to see them till Saturday night, when

they would be at home; appointed a place to see Vina,

in an open field, that night; they to bring me something

to eat; our interview only four minutes; I left;

appeared by night; dark and cloudy; at ten o'clock

appeared William; exchanged signals; led me a few

rods to where stood Vina; gave her the signal

sent by Peter; our interview ten minutes; she did

not call me "master," nor did she say "sir," by which I

knew she had confidence in me.

Our situation being dangerous, we decided that I meet

Peter and Levin on the bank of the river

early dawn of day, Sunday, to establish the laws.

During our interview, William prostrated on his

knees, and face to the ground; arms sprawling; head

cocked back, watching for wolves, by which position a

man can see better in the dark. No house to go to

safely, traveled round till morning, eating hoe cake

which William had given me for supper; next day

going around to get employment. I thought of

William who is a Christian preacher, and of the

Christian preachers in Pennsylvania. One watching

for wolves by night, to rescue Vina and her three

children from Christian licentiousness; the other

standing erect in open day, seeking the praise of men.

During the four days waiting for the important Sunday

morning, I thoroughly surveyed the rocks and shoals of

the river from Florence seven miles up, where will be my

place of departure. General notice was taken of me

as being a stranger, lurking around. Fortunately

there are several small grist mills within ten miles

around. No taverns here, as in the North; any

planter's house entertains travelers occasionally.

One night I stayed at a medical gentleman's, who is not

a large planter; another night at the ex-magistrate's

house in South Florence - a Virginian by birth - one of

the late census takers; told me that many more persons

cannot read and write than is reported; one fact,

amongst many others, that many persons who do not know

the letters of the alphabet, have learned to write their

own names; such are generally reported readers and

writers.

In being customary for a stranger not to leave the

house early in the morning where he has lodged. I

was under the necessity of staying out all night

Saturday, to be able to meet Peter and Levin,

which was accomplished in due time. When we

approached, I gave my signal first; immediately they

gave theirs. I talked freely. Levin's

voice, at first, evidently trembled. No wonder,

for my presence universally attracted attention by the

lords

[Pg. 28]

of the land. Our interview was less than one hour;

the laws were written. I to go to Cincinnati to

get a rowing boat and provisions; a first class clipper

boat to go with speed. To depart from the place

where the laws were written, on Saturday night of the

first of March. I to meet one of them at the

same place Thursday night, previous to the fourth

Saturday from the night previous to the Sunday when the

laws were written. We go to down the Tennessee

river to some place up the Ohio, not yet decided on, in

our row boat. Peter and Levin are

good oarsmen. So am I. Telegraphy station at

Tuscombia, twelve miles from the plantation, also at

Paducah.

Came from Florence to here Sunday night by steamboat.

Eastport is in Mississippi. Waiting here for a

steamboat to go down; paying one dollar a day for board.

Like other taverns here, the wretchedness is

indescribable; no pen, ink, paper or newspaper to be

had; only one room for everybody, except the gambling

rooms. It is difficult for me to write.

Vina intends to get a pass for Catharine and

herself for the first Sunday in March.

The bank of the river where I met Peter and

Levin is two miles from the plantation. I have

avoided saying I am from Philadelphia. Also

avoided talking about negroes. I never talked so

much about milling before. I consider most of the

trouble over, till I arrive in a free State with my

crew, the first week in March; then will I have to be

wiser than Christian serpents, and more cautious than

doves. I do not consider it safe to keep business

in these post-offices that notice might be taken.

I am evidently watched; everybody knows me to be a

miller. I may wright again, when I get to

Cincinnati. If I should have time. The

ex-magistrate, with whom I stayed in South Florence,

held three hours' talk with me, exclusive on our morning

talk. Is a man of good general information; he was

exceedingly inquisitive. "I am from Cincinnati,

formerly from the State of New York." I had

no opportunity to get anything to eat from seven o'clock

Tuesday morning till six o'clock Wednesday evening,

except the hoe cake, and no sleep.

Florence is the head of navigation for small

steamboats. Seven miles, all the way up to my

place of departure, is swift water, and rocky.

Eight hundred miles to Cincinnati. I found all

things here as Peter told me, except the distance

of the river. South Florence contains twenty white

families, three warehouses of considerable business, a

post-office, but no school. McKiernon is

here waiting for a steamboat to go to New Orleans, so we

are in company.

PRINCETON,

GIBSON

COUNTY,

INDIANA,

FEB.

18, 1851.

To WM.

STILL:

- The plan is to go to Canada, on the Wabash, opposite

Detroit. There are four routes to Canada.

One through Illinois, commencing above and below Alton;

one through the North Indiana, and the Cincinnati route,

being the largest route in the United States.

I intended to have gone through Pennsylvania, but the

risk going up the Ohio river has caused me to go to

Canada. Steamboat traveling is universally

condemned; though many go in boats, consequently many

get lost. Going in a skiff is new, and is approved

of in my case. After I arrive at the mouth of the

Tennessee river, I will go up the Ohio seventy-five

miles, to the mouth of the Wabash, then up the Wabash,

forty-four miles to New Harmony, where I shall go ashore

by night, and go thirteen miles east, to Charles

Grier a farmer, (colored man), who will entertain

us, and next night convey us sixteen miles to David

Stormon, near Princeton, who will take the command,

and I be released.

David Stormon estimates the expenses from his

house to Canada, at forty dollars, without which, no

sure protection will be given. They might be

instructed concerning the course, and beg their way

through without money. If you wish to do what

should be done, you will send my fifty dollars, in a

letter, to Princeton, Gibson county, Inda., so as

[Pg. 29]

to arrive there by the 8th of March. Eight days

should be estimated for a letter to arrive from

Philadelphia.

The money to be State Bank of Ohio, or State Bank, or

Northern Bank of Kentucky, or any other Eastern bank.

Send no notes larger than twenty dollars.

Levi Coffin had no money for me. I paid

twenty dollars for the skiff. No money to get back

to Philadelphia. It was not understood that I

would have to be at any expense seeking aid.

One half of my time has been used in trying to find

persons to assist, when I may arrive on the Ohio river,

in which I have failed, except Stormon.

Having no letter of introduction to Stormon from any

source, on which I could fully rely, I traveled two

hundred miles around, to find out his stability. I

have found many abolitionists, nearly all who have made

propositions, which themselves would not comply with,

and nobody else would. Already I have traveled

over three thousand miles. Two thousand and four

hundred by steamboat, two hundred by railroad, one

hundred by stage, four hundred on foot, forty-eight in a

skiff.

I have yet five hundred miles to go to the plantation,

to commence operations. I have been two weeks on

the decks of steamboats, three nights out, two of which

I got perfectly wet. If I had had paper money, as

McKim desired, it would have been destroyed.

I have not been entertained gratis at any place except

Stormon's. I had one hundred and twenty-six

dollars when I left Philadelphia, one hundred from you,

twenty-six mine.

Telegraphed to station at Evansville, thirty-three

miles from Stormon's, and at Vinclure's, twenty-five

miles from Stormon's. The Wabash route is

considered the safest route No one has ever been

lost from Stormon's to Canada. Some had been lost

between Stormon's and the Ohio. The wolves have

never suspected Stormon. Your asking aid in money

for a case properly belonging east of Ohio, is detested.

If you have sent money to Cincinnati, you should recall

it. I will have no opportunity to use it.

SETH

CONCKLIN,

Princeton, Gibson county, Ind.

P. S. First of April, will be about the time Peter's

family will arrive opposite Detroit. You should

inform yourself how to find them there. I may have

no opportunity.

I will look promptly for your letter at Princeton, till

the 10th of March, and longer if there should have been

any delay by the mails.

In March, as

contemplated, Concklin arrived in Indiana, at the

place designated, with Peter's wife and three

children, and sent a thrilling letter to the writer,

portraying in the most vivid light his adventurous

flight from the hour they left Alabama until their

arrival in Indiana. In this report he stated, that

instead of starting early in the morning, owing to some

unforeseen delay on the part of the family, they did not

reach the designated place till towards day, which

greatly exposed them in passing a certain town which he

had hoped to avoid.

But as his brave heart was bent on prosecuting his

journey without further delay, he concluded to start at

all hazards, notwithstanding the dangers he apprehended

from passing said town by daylight. For safety he

endeavored to hide his freight by having them all lie

flat down on the bottom of the skiff; covered them with

blankets, concealing them from the effulgent beams of

the early morning sun, or rather from the "Christian

Wolves" who might perchance espy him from the shore in

passing the town.

[Pg. 30]

The wind blew fearfully. Concklin was

rowing heroically when loud voices from the shore hailed

him, but he was utterly deaf to the sound.

Immediately one or two guns were fired in the direction

of the skiff, but he heeded not this significant call;

consequently here ended this difficulty. He

supposed, as the wind was blowing so hard, those on

shore who hailed him must have concluded that he did not

hear them and that he meant no disrespect in treating

them with seeming indifference. Whilst many

straits and great dangers had to be passed, this was the

greatest before reaching their destination.

But suffice it to say that the glad tidings which this

letter contained filled the breast of Peter with

unutterable delight and his friends and relations with

wonder beyond degree.* No fond wife had ever

waited with more longing desire for the return of her

husband than Peter had for this blessed news.

All doubts had disappeared, and a well grounded hope was

cherished that within a few short days Peter and

his fond wife and children would be reunited in Freedom

on the Canada side, and that Concklin and the

friends would be rejoicing with joy unspeakable over

this great triumph. But alas, before the few days

had expired the subjoined brief paragraph of news was

discovered in the morning Ledger.

RUNAWAY

NEGROES CAUGHT

- At Vincennes, Indiana, on Saturday last, a white man

and four negroes were arrested. The negroes belong

to B. McKiernon of South Florence, Alabama, and

the man who was running them off calls himself John

H. Miller. The prisoners were taken charge of

by the Marshall of Evansville. -

April 9th.

How

suddenly these sad tidings turned into mourning and

gloom the hope and joy of Peter and his relatives

no pen could possibly describe; at least the writer will

not attempt it here but will at once introduce a witness

who met the noble Concklin and the panting

fugitives in Indiana and proffered them sympathy and

advice. And it may safely be said from a truer and

more devoted friend of the slave they could not have

received counsel.

EVANSVILLE,

INDIANA,

MARCH

31st, 1851

WM. STILL: Dear Sir, - On last

Tuesday I mailed a letter to you, written by Seth

Concklin. I presume you have received that

letter. I gave an account of his rescue of the

family of your brother. If that is the last news

you have from them, I have very painful intelligence for

you. they passed on from near Princeton,

where I saw them and had a lengthy interview with them,

up north, I think twenty-three miles above Vincennes,

Ind., where they were seized by a party of men, and

lodged in jail. Telegraphic dispatches were sent

all through the South. I have since learned that

the Marshall of Evansville received a dispatch from

Tuscumbia, to look out for them. By some means, he

and the master, so says report, went to Vincennes and

claimed the fugitives, chained Mr. Concklin and

hurried all off. Mr. Concklin wrote to

Mr. David Stormon, Princeton, as soon as he was cast

into prison, to find bail. So soon as we got the

letter and could get off, two of us were about setting

off to render all possible aid, when we were told they

-------------------------

* In some unaccountable manner

this the last letter Concklin ever penned,

perhaps, ahs been unfortunately lost.

[Pg. 31]

all had passed, a few hours before, through Princeton,

Mr. Concklin in chains. What kind of

process was had, if any, I know not. I immediately

came down to this place, and learned that they had been

put on a boat at 3 P. M. I did not arrive until 6.

Now all hopes of their recovery are gone. No case

ever so enlisted my sympathies. I had seen Mr.

Concklin in Cincinnati. I had given him aid

and counsel. I happened to see them after they

landed in Indiana. I heard Peter and

Levin tell their tale of suffering, shed tears of

sorrow for them all; but now, since they have fallen a

prey to the unmerciful blood hounds of this state, and

have again been dragged back to unrelenting bondage, I

am entirely unmanned. And poor Concklin!

I fear for him. When he is dragged back to

Alabama, I fear they will go far beyond the utmost rigor

of the law, and vent their savage cruelty upon him.

It is with pain I have to communicate these things.

But you may not hear them from him. I could not

get to see him or them, as Vincennes is about thirty

miles from Princeton, where I was when I heard of the

capture.

I take pleasure in stating that, according to the

letter he (Concklin) wrote to Mr. D. Stewart,

Mr. Concklin did not abandon them, but risked his

own liberty to save them. He was not with them

when they were taken; but went afterwards to take them

out of jail upon a writ of Habeas Corpus, when they

seized him too and lodged him in prison.

I write in much haste. If I can learn any more

facts of importance, I may write you. If you

desire to hear from me again, or if you should learn any

thing specific from Mr. Concklin, he pleased to

write me at Cincinnati, where I expect to be in a short

time. If curious to know your correspondent, I may

say I formerly Editor of the "New Concord Free Press,"

Ohio. I only add that every case of this kind only

tends to make me abhor my (no!) this country more

and more. It is the Devil's Government, and God

will destroy it.

Yours for the slave,

N. R. JOHNSTON

P. S. I

broke open this letter to write you some more. The

foregoing pages were written at night. I expected

to mail it next morning before leaving Evansville; but

the boat for which I was waiting came down about three

in the morning; so I had to hurry on board, bringing the

letter along. As it now is I am not sorry, for

coming down, on my way to St. Louis, as far as Paducah,

there I learned from a colored man at the wharf that,

that same day, in the morning, the master and the family

of fugitives arrived off the boat, and had then gone in

their journey to Tuscumbia, but that the "white man" (Mr.

Concklin) had got away from them," about twelve

miles up the river. It seems he got off the boat

some way, near or at Smithland, Ky., a town at the mouth

of the Cumberland River. I presume the report is

true, and hope he will finally escape, though I was also

told that they were in pursuit of him. Would have

the others had also escaped. Peter and

Levin could have done so, I think, if they had had

resolution. One of them rode a horse, he not tied

either, behind the coach in which the others were.

He followed apparently "contented and happy." From

report, they told their master, and even their pursuers,

before the master came, that Concklin had decoyed

them away, they coming unwillingly. I write on a

very unsteady boat.

Yours, N. R. JOHNSTON.

A report found its way into the papers to the effect

that "Miller," the white man arrested in connection with

the capture of the family, was found drowned, with his

hands and feet in chains and his skull fractured.

It proved as his friends feared to be Seth Concklin.

And in irons, upon the river bank, there is no doubt he

was buried.

In this dreadful hour one sad duty remained to be

performed. Up to this moment the two sisters were

totally ignorant of their brother's whereabouts.

Not the first whisper of his death had reached them.

But they must now be made acquainted with all the facts

in the case. Accordingly

[Pg. 32]

an interview was arranged for a meeting, and the duty of

conveying this painful intelligence to one of the

sisters, Mrs. Supplee, devolved upon Mr. McKim.

And most tenderly and considerably did he perform his

mournful task.

Although a woman of nerve, and a true friend to the slave, an

earnest worker and a liberal giver in the Female

Anti-Slavery Society, for a time she was overwhelmed by

the intelligence of her brother's death. As soon

as possible, however, through very great effort, she

controlled her emotions, and calmly expressed herself as

being fully resigned to the awful event. Not a

word of complaint had she to make because she had not

been apprised of his movements; but said repeatedly,

that, had she known ever so much of his intentions, she

would have been totally powerless in opposing him if she

had felt so disposed, and as an illustration of the true

character of the man, from his boyhood up to the day he

died for his fellowman, she related his eventful career,

and recalled a number of instances of his heroic and

daring deeds for others, sacrificing his time and often

periling his life in the cause of those who he

considered were suffering gross wrongs and oppression.

Hence, she concluded, that it was only natural for him

in this case to have taken the steps he did. Now

and then overflowing tears would obstruct this deeply

thrilling and most remarkable story she was telling of

her brother, but her memory seemed quickened by the

sadness of the occasion, and she was enabled to recall

vividly the chief events connected with his past

history. Thus his agency in this movement, which

cost him his life, could readily enough be accounted

for, and the individuals who listened attentively to the

story were prepared to fully appreciate his character,

for, prior to offering his services in this mission, he

had been a stranger to them.

The following extract, taken from a letter of a

subsequent date, in addition to the above letter, throws

still further light upon the heart-rending affair, and

shows Mr. Johnston's deep sympathy with the

sufferers and the oppressed generally -

EXTRACT OF A LETTER FROM REV. N. R.

JOHNSTON.

My heart bleeds when I think of those poor, hunted and

heart-broken fugitives, though a most interesting

family, taken back to bondage ten-fold worse than

Egyptian. And then poor Concklin! How

my heart expanded in love to him, as he told me his

adventures, his trials, his toils, his fears and his

hopes! After hearing all, and then seeing and

communing with the family, now joyful in hopes of soon

seeing their husband and father in the land of freedom;

now in terror lest the human blood-hounds should be at

their heels, I felt as though I could lay down my life

in the cause of the oppressed. In that hour or two

of intercourse with Peter's family, my heart

warmed with love to them. I never saw more

interesting young men. They would make Remonds

or Douglasses, if they had the same

opportunities.

While I was with them, I was elated with joy at their

escape, and yet, when I heard their tale of woe,

especially that of the mother, I could not suppress

tears of deepest emotion.

[Pg. 33]

My joy was short-lived. Soon I heard of their

capture. The telegraph had been the means of their

being claimed. I could have torn down all the

telegraph wires in the land. It was a strange

dispensation of Providence.

On Saturday the sad news of their capture came to my

ears. We had resolved to go to their aid on

Monday, as the trial was set for Thursday. On

Sabbath, I spoke from Psalm xii. 5. "For the

oppression of the poor, for the sighing of the needy,

now will I arise," saith the Lord: "I will set him in

safety from him that puffeth at (from them that would

enslave) him." When on Monday morning I learned

that the fugitives had passed through the place on

Sabbath, and Concklin in chains, probably at the

very time I was speaking on the subject referred to, my

heart sank within me. And even yet, I cannot but

exclaim, when I think of it - O, Father! how long are

Thou wilt arise to avenge the wrongs of the poor slave!

Indeed, my dear brother, His way are very mysterious.

We have the consolation, however, to know that all is

for the best. Our Redeemer does all things well.

When He hung upon the cross, His poor broken-hearted

disciples could not understand the providence; it was a

dark time to them; and yet that was an event that was

fraught with more joy to the world than any that has

occurred or could occur. Let us stand at our post,

and wait God's time. Let us have on the whole

armor of God, and fight for the right, knowing that

though we may fall in battle, the victory will be ours,

sooner or later.

*

* *

* *

* *

* *

* *

May God lead

you into all truth, and sustain you in your labors, and

fulfill your prayers and hopes.

Adieu.

N. R. JOHNSTON

LETTERS FROM LEVI COFFIN.

The following

letters on the subject were received from the untiring

and devoted friend of the slave, Levi Coffin, who

for many years had occupied in Cincinnati a similar

position to that of Thomas Garrett in Delaware, a

sentinel and watchman commissioned for God to succor the

fleeing bondman -

CINCINNATI, 4TH

MO., 10TH

1851.

FRIEND

WM. STILL:

- We have sorrowful news from our friend Concklin,

through the papers and otherwise. I received a

letter a few days ago from a friend near Princeton,

Ind., stating that Concklin and the four slaves

are in person in Vincennes, and that their trial would

come on in a few days. He states that they rowed

seven days and nights in the skiff and got safe to

Harmony, Ind., on the Wabash river, thence to Princeton,

and were conveyed to Vincennes by friends, where they

were taken. The papers state, that they were all

given up to the Marshal of Evansville, Indiana.

We have telegraphed to different points, to try to get

some information concerning them, but failed. The

last information is published in the Times of

yesterday, though quite incorrect in the particulars of

the case. Inclosed is the slip containing it.

I fear all is over in regard to the freedom of the

slaves. If the last account be true, we have some

hope that Concklin will escape from those bloody

tyrants. I cannot describe my feelings on hearing

this sad intelligence. I feel ashamed to own my

country. Oh I what shall I say. Surely a God

of justice will avenge the wrongs of the oppressed.

Thine for the poor slave,

LEVI COFFIN

N. B. - If thou

hast any information, please write me forthwith.

CINCINNATI, 5TH,

MO., 11TH,

1851.

WM.

STILL: - Dear Friend -

Thy letter of 1st inst., came duly to hand, but not

being able to give any further information concerning

our friend, Concklin, I thought best to wait a

little before I wrote, still hoping to learn something

more definite concerning him.

[Pg. 34]

We that became acquainted with Seth Concklin and

his hazardous enterprises (here at Cincinnati), where

were very few, have felt intense and inexpressible

anxiety about them. And particularly about poor

Seth, since we heard of his falling into the hands

of the tyrants. I fear that he has fallen a victim

to their to their inhuman thirst for blood.

I seriously doubt the rumor, that he had made his

escape. I fear that he was sacrificed.

Language would fail to express my feelings; the intense

and deep anxiety I felt about them for weeks before I

heard of their capture in Indiana, and then it seemed

too much to bear. O! my heart almost bleeds when I

think of it. The hopes of the dear family all

blasted by the wretched blood-hounds in human shape.

And poor Seth, after all his toil, and dangerous,

shrewd and wise management, and almost unheard of

adventures, the many narrow and almost miraculous

escapes. Then to be given up to Indianans, to

these fiendish tyrants, to be sacrificed. O!

Shame, Shame!!

My heart aches, my eyes fill with tears, I cannot write

more. I cannot dwell longer on this painful

subject now. If you get any intelligence, please

inform me. Friend N. R. Johnston who took

so much interest in them, and saw them just before they

were taken, has just returned to the city. He is a

minister of the Coventer order. He is truly a

lovely man, and his heart is full of the milk of

humanity;

one of our best Anti-Slavery spirits. I spent last

evening with him. He related the whole story to me

as he had had it form friend Concklin and the

mother and children, are then the story of their

capture. We wept together. He found they

letter when he got here.

He said he would write the whole history to thee in a

few days, as far as he could. He can tell it much

better than I can.

Concklin left his carpet sack and clothes here

with me, except a shirt or two he took with him.

What shall I do with them? For if we do not hear

from him soon, we must conclude that he is lost, and

there port of his escape all a hoax.

Truly thy friend,

LEVI COFFIN

Stunning and discouraging as this horrible ending was to

all concerned, and serious as the matter looked in the

eyes of Peter's friends with regard to Peter's

family, he could not for a moment abandon the idea of

rescuing them from the jaws of the destroyer. But

most formidable of rescuing them from the jaws of the

destroyer. But most formidable difficulties stood

in the way of opening correspondence with reliable

persons in Alabama. Indeed it seemed impossible to

find a merchant, lawyer, doctor, planter or minister,

who was not too completely interlinked with slavery to

be relied upon to manage a negotiation of this nature.

Whilst waiting and hoping for something favorable to

turn up, the subjoined letter from the owner of Peter's

family was received and is here inserted precisely as it

was written, spelled and punctuated -

McKIERNON'S LETTER.

SOUTH FLORENCE

ALA 6 Augest 1851

Mr. WILLIAM STILL

No 31 North Fifth street Philadelphia.

Sir a few days sinc mr Lewis Tarenton of

Tuscumbia Ala shewed me a letter dated 6 June 51 from

cincinnati signd samuel Lewis in behalf of a

Negro man by the name of peter Gist who informed

the writer of the Letter that you ware his brother and

wished an answer to be directed to you as he peter

would be in philadelphi. the object of the letter

was to purchis from me 4 Negros that is peters

wife & 3 children 2 sons & 1 Girl the Name of said

Negres are the woman Viney the (mother) Eldest

son peter 21 or 2 years old second son Leven

19 or 20 years 1 Girl about 13 or 14 years old.

the Husband & Father of these people once Belonged to a

relation of mine by the name of Gist now

[Pg. 35]

Decest & some few years since he peter was

sold to a man by the Name of Freedman who removed

to cincinnati ohio & Tuck peter with him of

course peter became free by the volentary act of

the master some time last march a white man by the name

of Miller apperd in the nabourhood & abducted the

bove negroes was caut at vincanes Indi with said negroes

& was there convicted of steling & remanded back to Ala

to Abide the penalty of the law & on his return met his

Just reward by Getting drownded at the mouth of

cumberland River on the ohio in attempting to make his

escape I recovered & Braught Back said 4 negroes or as

You would say coulard people under the Belief that

peter the Husband was accessery to the offence

thareby putting me to much Expense & Truble to the amt

$1000 which if he gets them he or his Friends must

refund these 4 negroes are worth in the market about

4000 for thea are Extraordinary fine & likely & but for

the fact of Elopement I would not take 8000 Dollars for

them but as the thing now stands you can say to peter

& his new discovered Relations in philadelphia I will

take 5000 for the 4 culerd people & if this will suite

him & he can raise the money I will delever to him or

his agent at paduca at mouth of Tennessee river said

negroes but the money must be Deposeted in the Hands of

some respectabl person at paduca before I remove the

property it wold not be safe for peter to come to

this countery write me a line on recpt of this & let me

Know peters views on the above

I am Yours &c

B. McKIERNON

WM. STILL'S ANSWER.

To

B. McKIERNON,

ESQ.: Sir - I have

received your letter from South Florence, Ala., under

date of the 6th inst. To say that it took me by

surprise, as well as afforded me pleasure, for which I

feel to be very much indebted to you, is no more than

true. In regard to your informants of myself -

Mr. Thornton, of Ala., and Mr. Samuel Lewis, of

Cincinnati - to them both I am a stranger.

However, I am the brother of Peter, referred to, and

with the fact of his having a wife and three children in

your service I am also familiar. This brother,

Peter, I have only had the pleasure of knowing for the

brief space of one year and thirteen days, although he

is now past forty and I twenty-nine years of age.

Time will not allow me at present, or I should give you

a detailed account of how Peter became a slave,

the forty long years which intervened between the time

he was kidnapped, when a boy, being only six years of

age, and his arrival in this city, from Alabama, one

year and fourteen days ago, when he was re-united to his

mother, five brothers and three sisters.

None but a father's

heart can fathom the anguish and sorrows felt by

Peter during the many vicissitudes through which he

has passed. H looked back to his boyhood and saw

himself snatched from the tender embraces of his parents

and home to be made a slave for life.

During all his prime days he was in the

faithful and constant service of those who had no just

claim upon him. In the meanwhile he married a

wife, who bore him eleven children, the greater part of

whom were emancipated from the troubles of life by

death, and three only survived. To them and his

wife he was devoted. Indeed I have never seen

attachment between parents and children, and wife, more

entire than was manifested in the case of Peter.

Through these many years of servitude, Peter

was sold and resold, from one State to another, from one

owner to another, till he reached the forty-ninth year

of his age, when, in a good Providence, through the

kindness of a friend and the sweat of his brow, he re-

[Pg. 36]

gained the God-given blessings of liberty. He

eagerly sought his parents and home with all possible

speed and pains, when, to his heart's joy, he found his

relatives.

Your present humble correspondent is the youngest of

Peter's brothers, and the first one of the family he

saw after arriving in this part of the country. I

think you could not fail to be interested in hearing how

we became known to each other, and the proof of our

being brothers, etc., all of which I should be most glad

to relate, but time will not permit me to do so.

The news of this wonderful occurrence, of Peter

finding his kindred, was published quite extensively,

shortly afterwards, in various newspapers, in this

quarter, which may account for the fact of "Miller's"

knowledge of the whereabouts of the "fugitives."

Let me say, it is my firm conviction that no one had any

hand in persuading "Miller" to go down from

Cincinnati, or any other place, after the family.

As glad as I should be, and as much as I would do for

the liberation of Peter's family (now no longer

young), and his three "likely" children, in whom he

prides himself - how much, if you are a father, you can

imagine; yet I would not, and could not, think of

persuading any friend to peril his life, as would be the

case, in an errand of that kind.

As regards the price fixed upon by you for the family,

I must say I do not think it possible to raise half that

amount, through Peter authorized me to say he

would give you twenty-five hundred for them.

Probably he is not as well aware as I am, how difficult

it is to raise so large a sum of money from the public.

The applications for such objects are so frequent among

us in the North, and have always been so liberally met,

that it is no wonder if many get tired of being called

upon. To be sure some of us brothers own some

property, but no great amount; certainly not enough to

enable us to hear so great a burden. Mother owns a

small farm in New Jersey, on which she has lived for

nearly forty years, from which she derives her support

in her old age. This small farm contains between

forty and fifty acres, and is the fruit of my father's

toil. Two of my brothers own small places also,

but they have young families, and consequently consume

nearly as much as they make, with the exception of

adding some improvements to their places.

For my own part, I am employed as a clerk for a living,

but my salary is quite too limited to enable me to

contribute any great amount towards so large a sum as is

demanded. Thus you see how we are situated

financially. We have plenty of friends, but little

money. Now, sir, allow me to make an appeal to

your humanity, although we are aware of your power to

hold as property those poor slaves, mother, daughter and

two sons, - that in no part of the United States could

they escape and be secure from your claim -

nevertheless, would your understanding, your heart, or

your conscience reprove you, should you restore to them,

without price, that dear freedom, which is theirs by

right of nature, or would you not feel a satisfaction in

so doing which all the wealth of the world could not

equal? At all events, could you not so reduce the

price as to place it in the power of Peter's

relatives and friends to raise the means for their

purchase? At first, I doubt not, but that you will

think my appeal very unreasonable; but, sir, serious

reflection will decide, whether the money demanded by

you, after all, will be of as great a benefit to you, as

the satisfaction you would find in bestowing so great a

favor upon those whose entire happiness in this life

depends mainly upon your decision in the matter.

If the entire family cannot be purchased or freed, what

can Vina and her daughter be purchased for?

Hoping sir, to hear from you, at your earliest

convenience, I subscribe myself.

Your obedient servant,

WM. STILL

To B. McKIERNON,

Esq.

No reply to this letter was ever received from

McKiernon. The cause of his reticence can be

as well conjectured by the reader as the writer.

Time will not admit of further details kindred to this

narrative. The life, struggles, and success of

Peter and his family were ably brought before

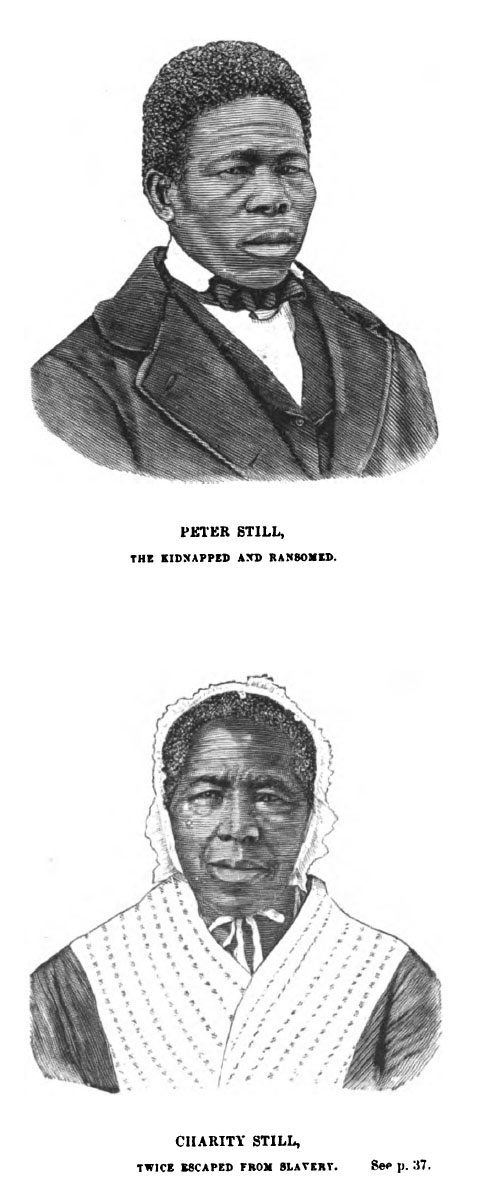

PETER STILL, The Kidnapped and Ransomed

CHARITY STILL, Twice Escaped from Slavery.

[Pg. 37]

the public in the "Kidnapped and the Ransomed," being

the personal recollections of Peter Still and his

wife "Vina," after forty years of slavery, by

Mrs. Kate E. R. Pickard; with an introduction by

Rev. Samuel J. May and an appendix by William H.

Furness, D. D., in 1856. But, of

course, it was not prudent or safe, in the days of

Slavery, to publish such facts as are now brought to

light; all such had to be kept concealed in the breasts

of the fugitives and their friends.

The following brief sketch, touching the separation of

Peter and his mother, will fitly illustrate this

point, and at the same time explain certain mysteries

which have been hitherto kept hidden -

THE SEPARATION.

With regard to

Peter's separation from his mother, when a little

boy, in few words, the facts were these: His parents,

Levins and Sidney, were both slaves on the

Eastern Shore of Maryland. "I will die before I

submit to the yoke," was the declaration of his father

to his young master before either was twenty-one years

of age. Consequently he was allowed to buy himself

a very low figure, and he paid the required sum and

obtained his "free papers" when quite a young man - the

young wife and mother remaining in slavery under

Saunders Griffin, as also her children, the latter

having increased to the number of four, two little boys

and two little girls. But to escape from chains,

stripes, and bondage, she took her four little children

and fled to a place near Greenwich, New Jersey.

Not a great while, however, did she remain there in a

state of freedom before the slave-hunters pursued her

and one night they pounced upon the whole family and

without judge or jury, hurried them all back to slavery.

Whether this was kidnapping or not is for the reader to

decide for himself.

Safe back in the hands of her owner, to prevent her

from escaping a second time, every night for about three

months she was cautiously "kept locked up in the

garret," until, as they supposed, she was fully "cured

of the desire to do so again." But she was

incurable. She had been a witness to the fact that

here own father's brains had been blown out by the

discharge of a heavily loaded gun, deliberately aimed at

his head by his drunken master. She only needed

half a chance to make still greater struggles than ever

for freedom.

She had great faith in God, and found much solace in

singing some of the good old Methodist tunes, by day and

night. Her owner, observing this apparently

tranquil state of mind, indicating that she "seemed

better contented than ever," concluded that it was safe

to let the garret door remain unlocked at night.

Not many weeks were allowed to pass before she resolved

to again make a bold strike for freedom. This time

she had to leave the two little boys, Levin and

Peter, behind.

On the night she started she went to the bed where they

were sleeping,

[Pg. 38]

kissed them, and, consigning him into the hands of God,

bade her mother good-bye, and with her two little girls

wended her way again to Burlington County, New Jersey,

but to a different neighborhood from that where she had

been seized. She changed her name to Charity,

and succeeded in again joining her husband, but, alas,

with the heart-breaking thought that she had been

compelled to leave her two little boys in slavery and

one of the little girls on the road for the father to go

back after. Thus she began life in freedom anew.

Levin and Peter, eight and six years of

age respectively, were now left at the mercy of the

enraged owner, and were soon hurried off to a Southern

market and sold, while their mother, for whom they were

daily weeping, was they knew not where. They were

too young to know that they were slaves, or to

understand the nature of the afflicting separation.

Sixteen years before Peter's return, his older

brother (Levin) died a slave in the State of

Alabama, and was buried by his surviving brother,

Peter.

No idea other than that they had been "kidnapped"

from their mother ever entered their minds; nor had they

any knowledge of the State from whence they supposed

they had been taken, the last names of their mother and

father, or where they were born. On the other

hand, the mother was aware that the safety of herself

and her rescued children depended on keeping the whole

transaction a strict family secret. During the

forty years of separation, except two or three Quaker

friends, including the devoted friend of the slave,

Benjamin Lundy, it is doubtful whether any other

individuals were let into the secret of her slave life.

And when the account give of Peter's return,

etc., was published in 1850, it led some of the family

to apprehend serious danger from the partial revelation

of the early condition of the mother, especially as it

was about the time that the Fugitive Slave law was

passed.

Hence, the author of "The Kidnapped and the Ransomed"

was compelled to omit these dangerous facts, and had to

confine herself strictly to the "Personal recollections

of Peter Still" with regard to his being

"kidnapped." Likewise, in the sketch of Seth

Concklin's eventful life, written by Dr. W. H.

Furness for similar reason he felt obliged to make

but bare reference to his wonderful agency in relation

to Peter's family, although he was fully aware of

all the facts in the case.

<

CLICK

HERE to GO to PAGES 39 to 63 >

|