|

STILL'S

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORDS,

REVISED EDITION.

(Previously Published in 1879 with title: The Underground Railroad)

WITH A LIFE OF THE AUTHOR.

NARRATING

THE HARDSHIPS, HAIRBREADTH ESCAPES AND DEATH STRUGGLES

OF THE

SLAVES

IN THEIR EFFORTS FOR FREEDOM.

TOGETHER WITH

SKETCHES OF SOME OF THE EMINENT FRIENDS OF FREEDOM, AND

MOST LIBERAL AIDERS AND ADVISERS OF THE ROAD

BY

WILLIAM STILL,

For many years connected with the Anti-Slavery Office in

Philadelphia, and Chairman of the Acting

Vigilant Committee of the Philadelphia Branch of the Underground

Rail Road.

Illustrated with 70 Fine Engravings

by Bensell, Schell and Others,

and Portraits from Photographs from Life.

Thou shalt not deliver unto his

master the servant that has escaped from his master unto thee. -

Deut. xxiii 16.

SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION.

PHILADELPHIA:

WILLIAM STILL, PUBLISHER

244 SOUTH TWELFTH STREET.

1886

pp. 39 - 63

[pg. 39]

UNDERGROUND RAILROAD

LETTERS

Here are

introduced a few out of a very large number of

interesting letters, designed for other parts of the

book as occasion may require. All letters will be

given precisely as they were written by their respective

authors, so that there may be no apparent room for

charging the writer with partial colorings in any

instance. Indeed, the originals, however

ungrammatically written or erroneously spelt, in their

native simplicity possess such beauty and force as

corrections and additions could not possibly enhance -

LETTER FROM THOMAS GARRETT (U. G. R.

R. DEPOT)

WILMINGTON, 3mo.

23d, 1856

DEAR

FRIEND, WILLIAM

STILL: - Since I wrote thee

this morning informing thee of the safe arrival of the

Eight from NOrfolk, Harry Craige has informed me,

that he has a man from Delaware that he proposes to take

along, who arrived since noon. He will take the

man, woman and two children from here with him, and the

four men will get in at Marcus Hook. Thee may take

Harry Craige by the hand as a brother, true to the

cause; he is one of our most efficient aids on the Rail

Road, and worthy of full confidence. May they all

be favored to get on safe. The woman and three

children are no common stock. I assure thee finer

specimens of humanity are seldom met with. I hope

herself and children may be enabled to find her husband,

who has been absent some years, and the rest of their

days be happy together.

I am, as ever, thy friend, THOS.

GARRETT.

LETTER FROM MISS G. A. LEWIS (U. G. R.

R. DEPOT)

KIMBERTON, October, 28th, 1855

ESTEEMED

FRIEND: - This evening a company of eleven friends

reached here, having left their homes on the night of

the 26th inst. They came into Wilmington, about

ten o'clock on the morning of the 27th, and left there,

in the town, their two carriages, drawn by two horses.

They went to Thomas Garrett's by open day-light

and from thence were sent hastily onward for fear of

pursuit. They reached Longwood meeting-house in

the evening, at which place a Fair Circle had convened,

and stayed a while in the meeting, then, after remaining

all night with one of the Kennet friends, they were

brought to Downingtown early in the morning, and from

thence, by daylight, to within a short distance of this

place.

They come from New Chestertown, within five miles of

the place from which the nine lately forwarded came, and

left behind them a colored woman who knew of their

intended flight and of their intention of passing

through Wilmington and leasing their horses and

carriages there.

I have been thus particular in my statement because the

case seems to us one of unusual danger. we have

separated the company for the present, sending a mother

and five children, two of them quite small, in one

direction, and a husband and wife and three lads in

another, until I could write to you and get advice if

you have any to give, as to the best method of

forwarding them, and assistance pecuniarily, in getting

them to Canada. The mother and children we have

sent off of the usual route, and to a place where I do

not think they can remain many days.

[Pg. 40]

We shall await hearing from you. H. Kimber

will be in the city on third day, the 30th, and any

thing left at 408 Green Street directed to his care,

will meet with prompt attention.

Please give me again the direction of Hiram Wilson

and the friend in Elmira, Mr. Jones I think.

If you have heard from any of the nine since their safe

arrival, please let us know when you write.

Very Respectfully, G. A. LEWIS.

2d day

morning, 29th. - The person who took the husband and

wife and three lads to E. F. Pennypacker, and

Peart, has returned and reports that L. Peart

sent three on to Norristown. We fear that there

they will fall into the hands of an ignorant colored man

Daniel Ross, and that he may not understand the

necessity of caution. Will you please write to

some careful person there? The woman and children

detained in this neighborhood to some careful person

there? The woman and children detained in this

neighborhood are a very helpless set. Our plan was

to assist them as much as possible, and when we get

things into the proper train for sending then on, to get

the assistance of the husband and wife, who have no

children, but are uncle and aunt to the woman with five,

in taking with them one of the younger children, leaving

fewer for the mother. Of the lads, or young men,

there is also one whom were thought capable of

accompanying one of the older girls - one to whom he is

paying attention, they told us. Would it not be

the best way to get those in Norristown under your own

care? It seems to me their being sent on could

then be better arranged. This, however, is only a

suggestion,

Hastily yours, G. A. LEWIS

LETTER FROM E. L. STEVENS, ESQ.

(The reader will interpret for himself.)

WASHINGTON, D.

C., July 11th, 1858.

MY

DEAR SIR: -

Susan Bell left here yesterday with the

child of her relative, and since leaving I have thought,

perhaps, you had not the address of the gentleman in

Syracuse where the child is to be taken for medical

treatment, etc. His name is Dr. H. B. Wilbur.

A woman living with him is a most excellent nurse and

will take a deep interest in the child, which, no doubt,

will under Providence be the means of its complete

restoration to health. Be kind enough to inform me

whether Susan is with you, and if she is give her

the proper direction. Ten packages were

sent to your address last evening, one of them belongs

to Susan, and she had better remain with you till

she gets it, as it may not have come to hand.

Susan thought she would go to Harrisburg when she

left here and stay over Sunday, if so, she would not get

to Philadelphia till Monday or Tuesday. Please

acknowledge the receipt of this, and inform me of her

arrival, also when the packages came safe to hand,

inform me especially if Susan's came safely.

Truly Yours,

E. L. STEVENS.

LETTER FROM S. H. GAY, ESQ., EX-EDITOR

OF THE ANTI-SLAVERY STANDARD AND NEW YORK TRIBUNE.

FRIEND

STILL: - The two women, Laura

and Lizzy, arrived this morning I shall

forward them to Syracuse this afternoon.

The two men came safely yesterday, but went to Gibbs'.

He has friends on board the boat who are on the lookout

for fugitives, and send them, when found, to his house.

Those whom you wish to be particularly under my charge,

must have careful directions to this office.

There is now no other sure place, but the office, or

Gibbs', that I could advise you to send such

persons. Those to me, therefore, must come in

office hours. In a few days, however, Napoleon

will have a room down town, and at odd times they can be

sent there. I am not willing to put any more with

the family where I have hitherto sometimes sent them.

[Pg. 41]

When it is possible I wish you would advise me two days

before a shipment of your intention, as Napoleon

is not always on hand to look out for them at short

notice. In special cases you might advise me by

Telegraph, thus: "One M. (or one F.) this morning.

W. S." By which I shall understand that one Male,

or one Female, as the case may be, has left Phihla. by

the 6 o'clock train - one or more, also, as the

case may be.

April 17th, 1855.

Truly Yours, S. H. GAY.

LETTER FROM JOHN H. HILL, A FUGITIVE,

APPEALING IN BEHALF OF A POOR SLAVE IN PETERSBURG, VA.

HAMILTON, Sept. 15th, 1856.

DEAR

FRIEND STILL:

- I write to inform you that Miss Mary Wever

arrived safe in this city. You may imagine the

happiness manifested on the part of the two lovers,

Mr. H. and Miss W. I think they will be

married as soon as they can get ready. I presume

Mrs. Hill will commence to make up the articles

to-morrow. Kind Sir, as all of us is concerned

about the welfare of our enslaved brethren at the South,

particularly our friends, we appeal to your sympathy to

do whatever is in your power to save poor Willis

Johnson from the hands of his cruel master. It

is not for me to tell you of his case, because Miss

Wever has related the matter fully to you. All

I wish to say is this, I wish you to write to my uncle,

at Petersburg, by our friend, the Capt. Tell my

uncle to go to Richmond and ask my mother whereabouts

this man is. The best for him is to make his way

to Petersburg; that is, if you can get the Capt. to

bring him. He have not much money. But I

hope the friends of humanity will not withhold their aid

on the account of money. However we will raise all

the money that is wanting to pay for his safe delivery.

You will please communicate this to the friends as soon

as possible.

Yours truly,

JOHN H. HILL.

LETTER FROM J. BIGELOW, ESQ.

WASHINGTON, D.

C., June 22d, 1854.

MR. WILLIAM

STILL: - Sir - I have just received a letter from

my friend, Wm. Wright, of Your Sulphur Springs,

Pa., in which he says, that by writing to you, I may get

some information about the transportation of some

property from this neighborhood to your city or

vicinity.

A person who signs himself Wm. Penn, lately

wrote to Mr. Wright, saying he would pay $300 to

have this service performed. It is for the

conveyance of only one SMALL package; but it has

been discovered since, that the removal cannot be so

safely effected without taking two larger

packages with it. I understand that the three

are to be brought to this city and stored in

safety, as soon as the forwarding merchant in

Philadelphia shall say he is ready to send on. The

storage, etc., here, will cost a trifle, but the $300

will promptly paid for the whole service. I think

Mr. Wright's daughter, Hannah, has also

seen you. I am also known to Prof. C. D.

Cleveland, of your city. If you answer this

promptly, you will soon hear from Wm. Penn

himself.

Yours truly,

J. BIGELOW.

LETTER FROM HAM & EGGS, SLAVE (U. G.

R. R. AG'T)

PETERSBURG, VA.,

Oct. 17th, 1860.

MR.

W. STILL: - Dear Sir -

I am happy to think, that the time has come when we no

doubt can open our correspondence with one another

again. Also I am in hopes, that these few lines

may find you and family well and in the enjoyment of

good health as it leaves me and family the same. I

want you to know, that I feel as much determined to work

in this glorious cause, as ever I did in all of my life,

and I have some very good

[Pg. 42]

hams on hand that I would like very much for you to

have. I have nothing of interest to write about

just now, only that the politics of the day is in a high

rage, and I don't know of the result, therefore, I want

you to be one of those wide a-wakes as is mentioned from

your section of country noe-a-days,&c. Also, if

you wish to write to me, Mr. J. Brown will inform

you how to direct a letter to me.

No more at present, until I hear from you; but I want

to be a wide-a-wake.

Yours in haste,

HAM & EGGS

LETTER FROM REV. H. WILSON (U. G. R.

R. AG'T)

ST. CATHARINE,

C. W., July 2d, 1855.

MY

DEAR FRIEND,

MR.

STILL:

- Mr. Elias Jasper and Miss Lucy Bell having

arrived here safely on Saturday last, and found their

"companions in tribulation," who had arrived before

them, I am induced to write and let you known the fact.

They are a cheerful, happy company, and very grateful

for their freedom. I have done the best I could

for their comfort, but they are about to proceed across

the lake to Toronto, thinking they can do better there

than here, which is not unlikely. They all

remember you as their friend and benefactor, and return

to you their sincere thanks. My means of support

are so scanty, that I am obliged to write without paying

postage, or not write at all. I hope you are not

moneyless, as I am. In attending to the wants of

numerous strangers, I am much of the time perplexed from

lack of means; but send on as many as you can and I will

divide with them to the last crumb.

Yours truly,

HIRAM WILSON.

LETTER FROM SHERIDAN FORD, IN DISTRESS

BOSTON, MASS.,

Feb. 15th, 1855.

No. 2, Change Avenue.

MY

DEAR FRIEND:

- Allow me to take the liberty of addressing you and at

the same time appearing troublesomes you all friend.

but subject is so very important that i can not but ask

not in my name but in the name of the Lord and humanity

to do something for my Poor Wife and children who lays

in Norfolk Jail and have Been there for three month i

Would open myself in that frank and bones manner.

Which should convince you of my cencerity of Purpoest

don't shut your ears to the cry's of the Widow and the

orphant & i can but ask in the name of humanity and God

for he knows the heart of all men. Please ask the

friends humanity to do something for her and her two

lettle ones i cant do any thing Place as i am for i have

to lay low Please lay this before the churches of

Philadelphaise beg them in name of the Lord to do

something for him i love my freedom and if it would do

her and her two children any good i mean to change with

her but cant be done for she is Jail and you most no she

suffer for the jail in the South are not like yours for

any thing is good enough for negros the Slave hunters

Save & may God interpose in behalf of the demonstrative

Race of Africa Whom i claim desendent i am sorry to say

that friendship is only a name here but i truss it is

not so in Philada i would not have taken this liberty

had i not considered you a friend for you treaty as such

Please do all you can and Please ask the Anti Slavery

friends to do all they can and God will Reward them for

it i am shure for the earth is the Lords and the

fullness there of as this note leaves me not very well

but hope when it comes to hand it may find you and

family enjoying all the Pleasure life Please answer this

and Pardon me if the necessary sum can be required i

will find out from my brotherinlaw i am with respectful

consideration.

SHERIDAN W. FORD

Yesterday is

the first time i have heard from home Sence i left and i

have not got any thing yet i have a tear yet for my

fellow man it is in my eyes now for God knows it

[Pg. 43]

is tha truth i sue for your Pity and all and may God

open their hearts to Pity a poor Woman and two children.

The Sum is i believe 14 hundred Dollars Please write to

day for me and see if the cant do something for

humanity.

LETTER FROM E. F. PENNYPACKER (U. G.

R. R. DEPOT)

SCHUYLKILL, 11th

mo., 7th day, 1857.

WM.

STILL: - Respected Friend:

- There are three colored friends at my house now,

who will reach the city by the Phil. & Reading train

this evening. Please meet them.

Thine &c.,

E. F. PENNYPACKER.

We have within

the past 2 mos. passed 43 through our hands,

,transported most of them to Norristown in our own

conveyance.

E. F. P.

LETTER FROM JOS. C. BUSTILL (U. G. R.

R. DEPOT)

HARRISBURG, March

24, '56

FRIEND

STILL:

- I suppose ere this you have seen those five large and

three small packages I sent by way of Reading,

consisting of three men and women and children.

They arrived here this morning at 8½

o'clock and left twenty minutes past three. You

will please send me any information likely to prove

interesting in relation to them.

Lately we have formed a Society here, called the

Fugitive Aid Society. This is our first case, and

I hope it will prove entirely successful.

When you write, please inform me what signs or symbols

you make use of in your despatches, and any other

information in relation to operations of the Underground

Rail Road.

Our reason for sending by the Reading Road, was to gain

time; it is expected the owners will be in town this

afternoon, and by this Road we gained five hours' time,

which is a matter of much importance, and we may have

occasion to use it sometimes in future. In great

haste,

Yours with

great respect,

JOS. C. BUSTILL.

LETTER FROM A SLAVE SECRETED IN

RICHMOND.

RICHMOND, VA.,

Oct. 18th, 1860.

To

MR.

WILLIAM STILL:

- Dear Sir - Please do me the favor as to write

to my uncle a few lines in regard to the bundle that is

for John H. Hill, who lives in Hamilton, C. W.

Sir, if this should reach you, be assured that it comes

from the same poor individual that you have heard of

before; the person who was so unlucky, and deceived

also. If you write, address your letter John M.

Hill, care of Box No. 250. I am speaking of a

person who lives in P.va. I hope sir, you will

understand this is from a poor individual.

LETTER FROM G. S. NELSON (U. G. R. R.

DEPOT)

MR.

STILL: - My Dear Sir -

I suppose you are somewhat uneasy because the goods did

not come safe to hand on Monday evening, as you expected

- consigned from Harrisburg to you. The train only

was from Harrisburg to Reading, and as it happened, the

goods had to stay all night with us, and as some

excitement exists here about goods of the kind, we

thought it expedient and wise to detain them until we

could hear from you. There are two small boxes and

two large ones; we have them all secure; what had better

be done? Let us know. Also, as we can

learn. there are three more boxes still in Harrisburg.

Answer your communication at Harrisburg. Also,

fail not to answer this by the return to mail, as things

are rather critical, and you will oblige us.

G. S. NELSON,

Reading, May 27, '57.

We knew not that these goods were to come,

consequently we were all taken by surprise. When

you answer, use the word, goods. The reason of the

excitement, is: some

[Pg. 44]

three weeks ago a big box was consigned to us by J.

Bustill, of Harrisburg. We received it, and

forwarded it on to J. Jones, Elmira, and the next

day they were on the fresh hunt of said box; it got safe

to Elmira, as I have had a letter from Jones, and

all is safe.

Yours,

G. S. N.

LETTER FROM JOHN THOMPSON

MR. STILL:

- You will oblige me much Iff you will Direct this

Letter to Vergenia for me to my Mother & iff it well

sute you Beg her in my Letter to Direct hers to you &

you Can send it to me iff it sute your Convenience.

I am one of your Chattle.

JOHN THOMPSON,

Syracuse, Jeny 6th.

LETTER

FROM JOHN THOMPSON, A FUGITIVE, TO HIS MOTHER.

MY DEAR MOTHER:

- I have imbrace an opportunity of writing you these few

lines (hoping) that they may fine you as they Leave me

quite well I will now inform you how I am geting

I am now a free man Living By the sweet of

my own Brow and serving a nother man & giving him all I

Earn But what I make is mine and iff one Plase do

not sute me I am at Liberty to Leave and go some where

elce & can ashore you I think highly of Freedom and

would not exchange it for nothing that is offered me for

it I am waiting in a Hotel I suppose you Remember

when I was in Jail I told you the time would Be Better

and you see that the time has come when I Leave you my

heart was so full & youre But I new their was a Better

Day a head, & I have Live to see it I hird when I

was on the Underground R. Road that the Hounds was on my

Track but it was no go I new I was too far out of

their Reach where they would never smell my track when I

Leave you I was carred to Richmond & sold & From their I

was taken to North Carolina & sold & I Ran a way & went

Back to Virginia. Between Richmond & home & their

I was caught & Put in Jail & their I Remain till the oner come for me then I was taken & carred Back to

Richmond then I was sold to the man who I now Leave he

is nothing But a But of a Feller. Remember me to

your Husband & all in quirin Friends & say to Miss Rosa

that I am as Free as she is & more happier I no I am

getting $12 per month for what Little work I am Doing.

I hope to here from you a gain I your Son & ever

By

JOHN THOMPSON.

LETTER FROM "WM. PENN" (OF THE BAR)

WASHINGTON, D.

C., Dec. 9th, 1856.

DEAR

SIR: - I was unavoidably prevented

yesterday, from replying to yours of 6th instant, and

although I have made inquiries, I am unable to-day,

to answer your questions satisfactorily. Although

I know some of the residents of Loudon county, and have

often visited there, still I have not practiced much in

the Courts of that county. There are several of my

acquaintances here, who have lived in that county, and

possibly, through my assistance, your commissions

might be executed. If a better way shall not

suggest itself to you, and you see fit to give me the

facts in the case, I can better judge of my

ability to help you; but I know not the man resident

there, whom I would trust with an important suit.

this it is now some four or five weeks since,

that some packages left this vicinity, said to be from

fifteen to twenty in number, and as I suppose, went

through your hands. It was at a time of uncommon

vigilance here, and to me it was a matter of extreme

wonder, how and through whom, such a work was

accomplished. Can you tell me? It is

needful that I should know! Not for curiosity

merely, but for the good of others.

[Pg. 45]

An enclosed slip contains the marks of one of the

packages, which you will read and then immediately

burn.

If you can give me any

light that will benefit others, I am sure you

will do so.

A traveler here, very reliable, and who knows

his business, has determined not to leave home again

till spring, at least not without extraordinary

temptations."

I think, however, he or others, might be tempted to

travel in Virginia.

Yours,

WM. P.

LETTER FROM MISS THEODOCIA GILBERT

SKANEATELES (GLEN

HAVEN) CHUY.,

1851

WILLIAM

STILL: - Dear Friend and

Brother - A thousand thanks for your good, generous

letter!

It was so kind of you to have in mind my intense

interest and anxiety in the success and fate of poor

Concklin! That he desired and intended to

hazard an attempt of the kind, I well understood; but

what particular one, or that he had actually embarked in

the enterprise, I had not been able to learn.

His memory will ever be among the sacredly cherished

with me. He certainly displayed more real

disinterestedness, more earnest, unassuming devotedness,

than those who claim to be the sincerest friends

of the slave can often boast. What more Saviour-like

than the willing sacrifice he has rendered!

Such generosity! at such a moment!

The emotions it awakened no words can bespeak!

They are to be sought but in the inner chambers of one's

own son!! He as earnestly devised the means as

calmly counted the cost, and as unshrinkingly turned him

to the task, as if it were his own freedom he would have

won.

Through his homely features, and bumble garb, the

intrepidity of soul came out in all its lustre!

Heroism, in its native majesty, commanded one's

admiration and love!

Most truly can I enter into your sorrows, and painfully

appreciate the pang of disappointment which must have

followed this and intelligence. But so inadequate

are words to the consoling of such griefs, it were

almost cruel to attempt to syllable one's sympathies.

I cannot bear to believe, that Concklin has been

actually murdered, and yet I hardly dare hope it is

otherwise.

And the poor slaves, for whom he periled so much, into

what depths of hopelessness and woe are they again

plunged! But the deeper and blacker for the loss

of their dearly sought and new-found freedom. How

long must wrongs like these go unredressed?

"How long, O God, how long?"

Very truly yours,

THEODOCIA GILBERT.

[pg. 46]

WILLIAM BOX PEEL JONES

Came boxed up via Erricson line of Steamers

ARRIVED PER ERRICSON LINE OF STEAMERS,

WRAPPED IN STRAW AND BOXED UP, APRIL, 1859.

William

is twenty-five years of age, unmistakably colored,

good-looking, rather under the medium size, and of

pleasing manners. William had himself boxed

up by a near relative and forwarded by the Erricson

line of steamers. He gave the slip to Robert H.

Carr, his owner (a grocer and commission merchant),

after those wise, and for the following reasons:

For some time previous his master had been selling off

his slaves every now and then, the same as other

groceries, and this admonished William that he

was liable to be in the market any day; consequently, he

preferred the box to the auction-block.

He did not complain of having been treated very badly

by Carr, but felt that no man was safe while

owned by another. In fact, he "hated the very name

of slaveholder." The limit of the box not

admitting of straightening himself out he was taken with

the cramp on the road, suffered indescribable misery,

and had his faith taxed to the utmost, - indeed was

brought to the very verge of "screaming aloud" ere

relief came. However, he controlled himself,

though only for a short season, for before a great while

an excessive faintness came over him. Here nature

became quite exhausted. He thought he must "die;"

but his time had not yet come. After a severe

struggle he revived, but only to encounter a third

ordeal no less painful than the one through which he had

just passed. Next a very "cold chill" came over

him, which seemed almost to freeze the very blood in his

veins and gave him intense agony, from which he only

found relief on awaking, having actually fallen asleep

in that condition. Finally, however, he arrived at

Philadelphia, on a steamer, Sabbath morning. A

devoted friend of his, expecting him, engaged a carriage

and repaired to the wharf for the box. The bill of

lading and the receipt he had with him, and likewise

knew where the box was located on the boat.

Although he well knew freight was not usually delivered

on Sunday, yet his deep solicitude for the safety of his

friend determined him to do all that lay in his power to

rescue him from his perilous situation. Handing

his bill of lading to the proper officer looked at the

bill and said, "No, we do not deliver freight on

Sunday;" but, noticing the anxiety of the man, he

asked him if he would know it if he were to see it.

Slowly - fearing that too much interest manifested might

excite suspicion - he replied: "I think I should."

Deliberately looking around amongst all the "freight,"

he discovered the box,

[pg. 47]

and said, "I think that it is there." Said officer

stepped to it, looked at the directions on it, then at

the bill of lading, and said, "That is right, take it

along." Here the interest in these two bosoms was

thrilling in the highest degree. But the size of

the box was too large for the carriage, and the driver

refused to take it. Nearly an hour and a half was

spent in looking for a furniture car. Finally one

was procured, and again the box was laid hold of by the

occupant's particular friend, when, to his dread alarm,

the poor fellow within gave a sudden cough. At

this startling circumstance he dropped the box; equally

as quick, although dreadfully frightened, and, as if

helped by some invisible agency, he commenced singing,

"Hush, my babe, lie still and slumber," with the most

apparent indifference, at the same time slowly making

his way from the box. Soon his fears subsided, and

it was presumed that no one was any the wiser on account

of the accident, or coughing. Thus, after

summoning courage, he laid hold of the box a third time,

and the Rubicon was passed. The car driver,

totally ignorant of the contents of the box, drove to

the number to which he was directed to take it - left it

and went about his business. Now is a moment of

intense interest - now of inexpressible delight.

The box is opened, the straw removed, and the poor

fellow is loosed; and is rejoicing, I will venture to

say, as mortal never did rejoice, who had not been in

similar peril. This particular friend was scarcely

less overjoyed, however, and their joy did not abate for

several hours; nor was it confined to themselves, for

two invited members of the Vigilance Committee also

partook of a full share. This box man was named

Wm. Jones. He was boxed up in Baltimore by the

friend who received him at the wharf, who did not come

in the boat with him, but came in the cars and met him

at the wharf.

The trial in the box lasted just seventeen hours before

victory was achieved. Jones was well cared

for by the Vigilance Committee and sent on his way

rejoicing, feeling that Resolution, Underground Rail

Road, and Liberty were invaluable.

On his way to Canada, he stopped at Albany, and the

subjoined letter gives his view of things from that

stand-point -

MR. STILL:

- I take this opportunity of writing a few lines to

you hoping that tha may find you in good health and

femaly. i am well at present and doing well at

present i am now in a store and getting sixteen dollars

a month at the present. i fell very much oblige to

you and your family for your kindes to me while i was

with you i have got a long without any trub le a tal.

i am now in Albany City. give my lov to mrs and mr

miller and tel them i am very much a blige to them

for there kind ns, give my lov to my Brother more

Jones tell him i should like to here from him very

much and he must write. tel him to give my love to

all of my perticular frends and tel them i should like

to see them very much. tel him that he must come

to see me for i want to see him for sum thing very

perticler. please ansure this letter as soon as

posabul and excuse me for not writing sooner as i dont

write myself. no more at the present.

WILLIAM JONES,

derect

to one hundred 125 lydus, stt

[pg. 48]

His good friend returned to Baltimore the same day the

box man started for the North, and immediately

dispatched through the post the following brief letter,

worded in Underground Rail Road parables:

BALTIMO APRIL

16, 1859

W. STILL:

- Dear brother i have taken the opportunity of writing

you these few lines to inform you that i am well an

hoping these few lines may find you enjoying the same

good blessing please to write me word at what time was

it when isreal went to Jerico i am very anxious to hear

for thare is a mighty host will pass over and you and I

my brother will sing hally luja i shall notify you when

the great catastrophe shal take place No more at

the present but remain your brother.

N. L. J.

WESTLEY HARRIS ALIAS ROBERT JACKSON,

CRAVEN MATTERSON AND TWO BROTHERS

In setting out

for freedom, Wesley was the leader of this party.

After two nights of fatiguing travel at a distance of

about sixty miles from home, the young aspirants for

liberty were betrayed, and in an attempt made to capture

them a most bloody conflict ensued. Both fugitives

and pursuers were the recipients of severe wounds from

gun shots, and other weapons used in the contest.

Wesley bravely used his fire arms until almost

fatally wounded by one of the pursuers, who with a

heavily loaded gun discharged the contents with deadly

aim in his left arm, which raked the flesh from the bone

for a space of about six inches in length. One of

Wesley's companions also fought heroically and

only yielded when badly wounded and quite overpowered.

The two younger (brothers of C. Matterson) it

seemed made no resistance.

In order to recall the adventures of this struggle, and

the success of Wesley Harris, it is only

necessary to copy the report as then penned from the

lips of this young hero, while on the Underground Rail

Road, even then in a very critical state. Most

fearful indeed was his condition when he was brought to

the vigilance Committee in this City.

UNDERGROUND RAIL ROAD RECORD.

November 2d, 1853. - Arrived: Robert Jackson

(shot man), alias Wesley Harris; age

twenty-two years; dark color; medium height, and of

slender stature.

Robert was born in Martinsburg, Va., and was

owned by Philip Pendleton. From a boy he

had always been hired out. At the first of this

year he commenced services with Mrs. Carroll,

proprietress of the United States Hotel at Harper's

Ferry. Of Mrs. Carroll he speaks in very

grateful terms, saying that she was kind to him and all

the servants, and promised them their freedom at her

death. She excused herself for not giving them

[Pg. 49]

their freedom on the ground that her husband died

insolvent, leaving her the responsibility of settling

his debts.

But while Mrs. Carroll was very kind to her

servants, her manager was equally as cruel. About

a month before Wesley left, the overseer for some

trifling cause, attempted to flog him, but was resisted,

and himself flogged. This resistance of the slave

was regarded by the overseer as an unpardonable offence;

consequently he communicated the intelligence to his

owner, which had the desired effect on his mind as

appeared from his answer to the overseer, which was

nothing less than instructions that if he should again

attempt to correct Wesley and she should repel

the wholesome treatment, the overseer was to put him in

prison and sell him. Whether he offended again or

not, the following Christmas he was to be sold without

fail.

Wesley's mistress was kind enough to apprise him

of the intention of his owner and the overseer, and told

him that if he could help himself he had better do so.

So from that time Wesley began to contemplate how

he should escape the doom which had been planned for

him.

"A friend," says he, "by the name of C. Matterson,

told me that he was going off. Then I told him of

my master's writing to Mrs. Carroll concerning

selling, etc., and that I was going off too. We

then concluded to go together. There were two

others - brothers of Matterson - who were told of

our plan to escape, and readily joined with us in the

undertaking. So one Saturday night, at twelve

o'clock, we set out for the North. After traveling

upwards of two days and over sixty miles, we found

ourselves unexpectedly in Terrytown, Md. There we

were informed by a friendly colored man of the danger we

were in and of the bad character of the place towards

colored people, especially those who were escaping to

freedom; and he advised us to hide as quickly as we

could. We at once went to the woods and hid.

Soon after we had secreted ourselves a man came near by

and commenced splitting wood, or rails, which alarmed

us. We then moved to another hiding-place in a

thicket near a farmer's barn, where we were soon

startled again by a dog approaching and barking at us.

The attention of the owner of the dog was drawn to his

barking and to where we were. The owner of the dog

was a farmer. He asked us where we were going.

We replied to Gettysburg - to visit some relatives, etc.

He told us that we were running off. He then

offered friendly advice, talked like a Quaker, and urged

us to go with him to his barn for protection.

After much persuasion, we consented to go with him.

"Soon after putting us in his barn, himself and

daughter prepared us a nice breakfast, which cheered our

spirits, as we were hungry. For this kindness we

paid him one dollar. He next told us to hide on

the mow till eve, when he would safely direct us on our

road to Gettysburg. All, very much fatigued from

traveling, fell asleep, excepting myself; I could not

sleep; I felt as if all was not right.

[Pg. 50]

"About noon men were heard talking around the barn.

I woke my companions up and told them that that man had

betrayed us. At first they did not believe me.

In a moment afterwards the barn door was opened, and in

came the men, eight in number. One of the men

asked the owner of the barn if he had any long straw.

'Yes,' was the answer. So up on the mow came three

of the men, when, to their great surprise, as they

pretended, we were discovered. The question was

then asked the owner of the barn by one of the men, if

he harbored runaway negroes in his barn? He

answered 'No,' and pretended to be entirely ignorant of

their being in his barn. One of the men replied

that four negroes were on the mow, and he knew of it.

The men then asked us where we were going. We told

them to Gettysburg, that we had aunts and a mother

there. Also we spoke of a Mr. Houghman, a

gentleman we happened to have some knowledge of, having

seen him in Virginia. We were net asked for our

passes. We told them that we hadn't any, that we

had not been required to carry them where we came from.

They then said that we would have to go before a

magistrate, and if he allowed us to go on, well and

good. The men all being armed and furnished with

ropes, we were ordered to be tied. I told them if

they took me they would have to take me dead or

crippled. At that instant one of my friends cried

out -- 'Where is the man that betrayed us?' Spying him

at the same moment, he shot him (badly wounding him).

Then the conflict fairly began. The constable

seized me by the collar, or rather behind my shoulder.

I at once shot him with my pistol, but in consequence of

his throwing up his arm, which hit mine as I fired, the

effect of the load of my pistol was much turned aside;

his face, however, was badly burned, besides his

shoulder being wounded. I again fired on the

pursuers, but do not know whether I hit anybody or not.

I then drew a sword, I had brought with me, and was

about cutting my way to the door, when I was shot by one

of the men, receiving the entire contents of one load of

a double barreled gun in my left arm, that being the arm

with which I was defending myself. The load

brought me to the ground, and was able to make further

struggle for myself. I was then badly beaten with

guns, &c. In the meantime, my friend Craven,

who was defending himself, was shot badly in the face,

and most violently beaten until he was conquered and

tied. The two young brothers of Craven

stood still, without making the least resistance.

After we were fairly captured, we were taken to

Terrytown, which was in sight of where we were betrayed.

By this time I had lost so much blood from my wounds,

that they concluded my situation was too dangerous to

admit of being taken further; so I was made a prisoner

at a tavern, kept by a man named Fisher.

There my wounds were dressed and thirty-two shot were

taken from my arm. From three days I was crazy,

and they thought I would die. During the first two

weeks, while I was a prisoner at the tavern, I raised a

great deal of blood, and was considered in a very

dangerous condition - so much so that persons desiring

to see me were not

DESPERATE CONFLICT IN A BARN.

Pg. 51

permitted. Afterwards I began to get better, and was

then kept very privately - was strictly watched day and

night. Occasionally, however, the cook, a colored

woman (Mrs. Smith), would manage to get to see

me. Also James Matthews succeeded in

getting to see me; consequently, as my wounds healed,

and my senses came to me, I began to plan how to make

another effort to escape. I asked one of the

friends, alluded to above, to get me a rope. He got it.

I kept it about me four days in my pocket; in the

meantime I procured three nails. On Friday night,

October 14th, I fastened my nails in under the window

sill; tied my rope to the nails, threw my shoes out of

the window, put the rope in my mouth, then took hold of

it with my well hand, clambered into the window, very

weak, but I managed to let myself down to the ground.

I was so weak, that I could scarcely walk, but I managed

to hobble off to a place three quarters of a mile from

the tavern, where a friend had fixed upon for me to go,

if I succeeded in making my escape There I was

found by my friend, who kept me secure till Saturday

eve, when a swift horse was furnished by James Rogers,

and a colored man found to conduct me to Gettysburg.

Instead of going direct to Gettysburg, we took a

different road, in order to shun our pursuers, as the

news of my escape had created general excitement.

My three other companions, who were captured, were sent

to Westminster jail, where they were kept three weeks,

and afterwards sent to Baltimore and sold for twelve

hundred dollars a piece, as I was informed while at the

tavern in Terrytown."

The Vigilance Committee procured good medical attention

and afforded the fugitive time for recuperation,

furnished him with clothing and a free ticket, and

sent him on his way greatly improved in health, and

strong in the faith that, "He who would be free, himself

must strike the blow." His safe arrival in Canada,

with his thanks, were duly announced. And some

time after becoming naturalized, in one of his letters,

he wrote that he was a brakesman on the Great Western R.

R., (in Canada - promoted from the U. G. R. R.,) the

result of being under the protection of the British

Lion.

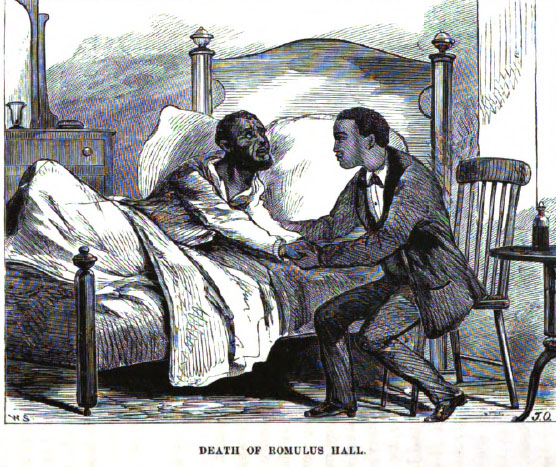

DEATH OF ROMULUS HALL - NEW NAME

GEORGE WEEMS.

In Marc,

1857, Abram Harris fled from John Henry

Suthern, who lived near Benedict, Charles county,

Md., where he was engaged i the farming business, and

was the owner of about seventy head of slaves. He

kept an overseer, and usually had flogging administered

daily, on males and females, old and young.

Abram becoming very sick of this treatment,

resolved, about the first of March, to seek out the

Underground Rail Road. But for his strong

attachment to his wife (who was owned by

Samuel

[Pg. 52]

Adams, but was "pretty well treated"), he never

would have consented to "suffer" as he did.

Here no hope of comfort for the future seemed to

remain. So Abram consulted with a fellow-servant,

by the name of Romulus Hall, alias George

Weems, and being very warm friends, concluded to

start together. Both had wives to "tear themselves

from," and each was equally ignorant of the distance

they had to travel and the dangers and sufferings to be

endured. But they "trusted in God" and kept the

North Star in view. For nine days and nights,

without a guide, they traveled at a very exhausting

rate, especially as they had to go fasting for three

days, and to endure very cold weather. Abram's

companion, being about fifty years of age, felt obliged

to succumb, both from hunger and cold, and had to be

left on the way. Abram was a man of medium

size, tall, dark chestnut color, and could read and

write a little and was quite intelligent; "was a member

of the Mount Zion Church," and occasionally officiated

as an "exhorter," and really appeared to be a man of

genuine faith in the almighty, and equally as much in

freedom.

In substance, Abram gave the following

information concerning his knowledge of affairs on the

farm under his master -

"Master and mistress very frequently visited the

Protestant Church, but were not members. Mistress

was very bad. About three weeks before I left, the

overseer, in a violent fit of bad temper, shot and badly

wounded a young slave man by the name of Henry Waters,

but no sooner than he got well enough he escaped, and

had not been heard of up to the time Abram left.

About three years before this happened, an overseer of

my master was found shot dead on the road. At once

some of the slaves were suspected, and were all taken to

the Court House, at Serentown, St. Mary's county; but

all came off clear. After this occurrence a new

overseer, by the name of John Decket,

nevertheless, concluded that it was not 'too late' to

flog the secret out of some of the slaves.

Accordingly, he selected a young slave man for his

victim, and flogged him so cruelly that he could

scarcely walk or stand, and to keep from being actually

killed, the boy told an untruth, and confessed that he

and his Uncle Henry killed Webster, the

overseer; whereupon the poor fellow was sent to jail to

be tried for his life."

But Abram did not wait to hear the verdict.

He reached the Committee safely in this city, in advance

of his companion, and was furnished with a free ticket

and other needed assistance, and was sent on his way

rejoicing. After reaching his destination, he

wrote back to know how his friend and companion (George)

was getting along; but in less than three weeks after he

had passed the following brief story reveals the sad

fate of poor Romulus Hall, who had

journeyed with him till exhausted from hunger and badly

frost-bitten.

A few days after his younger companion had passed on

North, Romulus

DEATH OF ROMULUS HALL

[Pg 53]

was brought by a pitying stranger to teh Vigilance

Committee, in a most shocking condition. The frost

had made sad havoc with his feet and legs, so much so

that all sense of feeling had departed therefrom.

How he ever reached thsi city is a marvel. On his

arrival medical attention and other necessary comforts

were provided by the Committee, who hoped with himself,

that he would be restored with the loss of hsi toes

alone. For one week he seemed to be improving; at

the expiration of this time, however, his symptoms

changed, indicating not only the end of slavery, but

also the end fo all his earthly troubles.

Lockjaw and mortification set in in the most malignant

form, and for nearly thirty-six hours the unfortunate

victim suffered in extreme agony, though not a murmur

escaped him for having brought upon himself in seeking

his liberty this painful infliction and death. It

was wonderful to see how resignedly he endured his fate.

Being anxious to get his testimony relative to his

escape, etc., the Chairman of the Committee took his

pencil and expressed to him his wishes in the matter.

Amongst other questions, he was asked: "Do you regret

having attempted to escape from slavery?" After a

severe spasm he said, as his friend was about to turn to

leave the room, hopeless of being gratified in his

purpose: "Don't go: I have not answered your question.

I am glad I escaped from slavery?

He then gave his name, and tried to tell the name of his master, but was

so weak he could not be understood.

At his bedside, day and night, Slavery looked more

heinous than it had ever done before. Only think

how this poor man, in an enlightened Christian land, for

the bare hope of freedom, in a strange land amongst

strangers, was obliged not only to bear the sacrifice of

his wife and kindred, but also of his own life.

Nothing ever appeared more sad than seeing him in a

dying posture, and instead of reaching his much coveted

destination in Canada, going to that "bourne whence no

traveler returns." Of course it was expedient,

even after his death, that only a few friends should

follow him to his grave. Nevertheless, he was

decently buried in the beautiful Lebanon Cemetery.

In his purse was found one single five cent piece, his

whole pecuniary dependence.

This was the first instance of death on teh Underground

Rail Road in this region.

The Committee were indebted to the medical services of

the well-known friends of the fugitive, Drs. J. L.

Griscom and H. T. Childs, whose faithful

services were freely given; and likewise to Mrs. H.

S. Duterte and Mrs. Williams, who generously

performed the offices of charity and friendship at his

burial.

From his companion, who passed on Canada-ward without

delay, we re-

[Pg. 54]

ceived a letter, from which, as an item of interest, we

make the following extract:

"I am enjoying

good health, and hope when this reaches you, you may be

enjoying the same blessing. Give my love to Mr.

____ _____, and family, and tell them I am in a land

of liberty~ I am a man among men~" (The

above was addressed to the deceased.)

The subjoined

letter, from Rev. L. D. Mansfield, expressed on

behalf of Romulus' companion, his sad feelings on

hearing of his friend's death. And here it may not

be inappropriate to add, that clearly enough is it to be

seen, that Rev. Mansfield was one of the rare

order of ministers, who believed it right "to do unto

others as one would be done by" in practice, not in

theory merely, and who felt that they could no more be

excused for "falling down," in obedience to the Fugitive

Slave Law under President Fillmore, than

could Daniel for worshiping the "golden image"

under Nebuchadnezzar.

AUBURN, NEW

YORK, MAY, 4TH,

1857.

DEAR

BR.

STILL: - Henry Lemmon

wishes me to write to you in reply to your kind letter,

conveying the intelligence of the death of your fugitive

guest, Geo. Weems. He was deeply affected

at the intelligence, for he was most devotedly attached

to hi and had been for many years. Mr. Lemmon

now expects his sister to come on, and wishes you to aid

her in any way in your power - as he knows you will.

He wishes you to send the coat and cap of Weems

by his sister when she comes. And when you write

out the history of Weems' escape, and it is published,

that you would send him a copy of the papers. He

has not been very successful in getting work yet.

Mr. and Mrs. Harris left for Canada last week.

The friends made them a purse of $15 or $20, and we hope

they will do well.

Mr. Lemmon sends his respects to you and Mrs.

Still. Give my kind regards to her and accept

also yourself,

Yours very truly,

L. D. MANSFIELD.

JAMES MERCER, WM. H. GILLIAM, AND

JOHN CLAYTON.

STOWED AWAY IN A HOT BERTH.

This

arrival came by Steamer. But they neither came in

State-room nor as Cabin, Steerage, or Deck passengers.

A certain space, not far from the boiler, where the

heat and coal dust were almost intolerable,- the colored

steward on teh boat in answer to an appeal from these

unhappy bondmen, could point to no other place for

concealment but this. Nor was he at all certain

that they could endure the intense heat of that place.

It admitted of no other posture than lying flat down,

wholly shut out from the light, and nearly in the same

predicament in regard to the air. Here, however,

was a chance of throwing off the yoke, even if it cost

them their lives. They considered and resolved to

try it at all hazards.

Henry Box Brown's sufferings were nothing,

compared to what these men submitted to during the

entire journey.

[Pg. 55]

They reached the house of one of the Committee about

three o'clock, A.M.

All the way from the wharf the cold rain poured down in

torrents and they got completely drenched, but their

hearts were swelling with joy and gladness unutterable.

From the thick coating of coal dust, and the effect of

the rain added thereto, all traces of natural appearance

were entirely obliterated, and they looked frightful in

the extreme. But they had placed their lives

in mortal peril for freedom.

Every step of their critical journey was reviewed and

commented on, with matchless natural eloquence, - how,

when almost on the eve of suffocating in their warm

berths, in order to catch a breath of air, they were

compelled to crawl, one at a time, to a small aperture;

but scarcely would insist that he should "go back to his

hole." Air was precious, but for the time being

they valued their liberty at still greater price.

After they had talked to their hearts' content, and

after they had been thoroughly cleansed and changed in

apparel, their physical appearance could be easily

discerned, which made it less a wonder whence such

outbursts of eloquence had emanated. They bore

every mark of determined manhood.

The date of this arrival was Feb. 26, 1854, and the

following description was then recorded -

Arrived, by Steamer Pennsylvania, James Mercer,

William H. Gilliam and John Clayton, from

Richmond.

James was owned by the widow, Mrs. T.

E. White. He is thirty-two years of age, of

dark complexion, well made, good-looking, reads and

writes, is very fluent in speech, and remarkably

intelligent. From a boy he had been hired out.

The last place he had the honor to fill before escaping,

was with Messrs. William and Brother,

wholesale commission merchants. For his services

in this store the widow had been drawing one hundred and

twenty-five dollars per annum, clear of all expenses.

He did not complain of bad treatment from his mistress,

indeed, he spoke rather favorably of her. But he

could not close his eyes to the fact, that at one time

Mrs. White had been in possession of thirty head

of slaves, although at the time he was counting the cost

of escaping, two only remained - himself and William,

save a little boy) and on himself a mortgage for seven

hundred and fifty dollars was then resting. He

could, therefore, with his remarkably quick intellect

calculate about how long it would be before he reached

the auction block.

He had a wife but no child. She was owned by

Mr. Henry W. Quarles. So out of that Sodom he

felt he would have to escape, even at the cost of

leaving his wife behind. Of course he felt hopeful

that the way would open by which she could escape at a

future time, and so it did, as will appear by and by.

His aged mother he had to leave also.

[Pg. 56]

Wm. Henry Gilliam likewise belonged to the

Widow White, and he had been hired to Messrs.

White and Brother to drive their bread wagon.

William was a baker by trade. For his

services his mistress had received one hundred and

thirty-five dollars per year. He thought his

mistress quite as good, if not a little better than most

slave-holders. But he had never felt persuaded to

believe that she was good enough for him to remain a

slave for her support.

Indeed, he had made several unsuccessful attempts

before this time to escape from slavery and its horrors.

He was fully posted from A to Z, but in his own person

he had been smart enough to escape most of the more

brutal outrages. He knew how to read and write,

and in readiness of speech and general natural ability

was far above the average of slaves.

He was twenty-five years of age, well made, of light

complexion, and might be put down as a valuable piece of

property.

This loss fell with crushing weight upon the

kind-hearted mistress, as will be seen in a letter

subjoined which she wrote to the unfaithful William,

some time after he had fled.

LETTER FROM MRS. L. E. WHITE.

RICHMOND, 16th,

1854

DEAR

HENRY: - Your mother and

myself received your letter; she is much distressed at

your conduct; she is remaining just as you left her, she

says, and she will never been reconciled to our conduct.

I think Henry, you have acted most dishonorably;

had you have made a confidant of me I would have been

better off; and you as you are. I am badly

situated, living with Mrs. Palmer, and having to

put up with everything - your mother is also

dissatisfied - I am miserably poor, do not get a cent of

your hire or James', besides losing you both, but

if you can reconcile so do. By renting a

cheap house, I might have lived, now it seems starvation

is before me. Martha and the Doctor are

living in Portsmouth, it is not in her power to do much

for me. I know you will repent it. I heard

six weeks before you went, that you were trying to

persuade him off - but we all liked you, and I was

unwilling to believe it - however, I leave it in God's

hands He will know what to do. Your mother says

that I must tell you servant Jones is dead and

old Mrs. Galt. Kit is well,

but we are very uneasy, losing your and James'

hire, I fear poor little fellow, that he will

be obliged to go, as I am compelled to live, and it will

be your fault. I am quite unwell, but of course,

you don't care.

Yours,

L. E. White

This touching

epistle was given by the disobedient William to a

member of the Vigilant Committee, when on a visit to

Canada, in 1855, and it was thought to be of too much

value to be lost. It was put away with other

valuable U. G. R. R. documents for future reference.

Touching the "rascality" of William and James and

the unfortunate predicament in which it placed the

kind-hearted widow, Mrs. Louisa White, the

following editorial clipped from the wide-awake Richmond

Despatch, was also highly

[Pg. 57]

appreciated, and preserved as conclusive testimony to

the successful working of the U. G. R. R. in the Old

Dominion. It reads thus -

"RASCALITY

SOMEWHERE. - We called attention yesterday to the

advertisement of two negroes belonging to Mrs. Louisa

White, by Toler & Cook, and in the call we

expressed the opinion that they were still lurking about

the city, preparatory to going off. Mr. Toler,

we find, is of a different opinion. He believes

that they have already cleared themselves - have escaped

to a Free State, and we think it extremely probably that

he is in the right. They were both of them

uncommonly intelligent negroes. One of them, the

one hired to Mr. White, was a tip-top baker.

He had been all about the country, and had been in the

habit of supplying the U. S. Pennsylvania with bread;

Mr. W. having the contract. In his visits for

this purpose, of course, he formed acquaintances with

all sorts of sea-faring characters; and there is every

reason to believe that he has been assisted to get off

in that way, along with the other boy, hired to the

Messrs. Williams. That the two acted in

concert, can admit of no doubt. The question is

now to find out how they got off. They must

undoubtedly have had white men in the secret.

Have we then a nest of Abolition scoundrels among us?

There ought to be a law to put a police officer on board

every vessel as soon as she lands at the wharf.

There is one, we believe for inspecting vessels before

they leave. If there is not there ought to be one.

"These negroes belong to a widow lady and constitute

all the property she has on earth. They have both

been raised with the greatest indulgence. Had it

been otherwise, they would have had an opportunity to

escape, as they have done. Their flight has left

her penniless. Either of them would readily have

sold for $1200; and Mr. Toler advised their owner

to sell them at the commencement of the year, probably

anticipating the very thing that has happened. She

refused to do so, because she felt to much attachment to

them. They have made a fine return, truly."

No comment is necessary on the above editorial except

simply to express the hope that the editor and his

friends who seemed to be utterly befogged as to how

these "uncommonly intelligent negroes: made their

escape, will find the problem satisfactorily solved in

this book.

However, in order to do even-handed justice to all

concerned, it seems but proper that William and

James should be heard from, and hence a letter

from each is here appended for what they are worth.

True they were intended only for private use, but since

the "True light" (Freedom) has come, all things may be

made manifest.

LETTER FROM WILLIAM HENRY GILLIAM.

ST. CATHARINES,

C. W., MAY 15th, 1854

[Pg. 58]

About my being in A free State, I am and think A great

del of it. Also I have no compassion on the

penniless widow lady, I have Served her 25 yers 2

months, I think that is long Enough for me to live A

Slave. Dear Sir, I am very sorry to hear of the

Accadent that happened to our Friend Mr. Meakins,

I have read the letter to all that lives in St.

Catharines, that came from old Virginia, and then I

Sented to Toronto to Mercer & Clayton to see, and

to Farman to read for themselves. Sir, you

must write to me soon and let me know how Meakins

gets on with his tryal, and you must pray for him, I

have told all here to do the same for him. May God

bless and protect him from prison, I have heard A great

del of old Richmond and Norfolk. Dear Sir, if you

see Mr. or Mrs. Gilbert Give my love to them and

tell them to write to me, also give my respect to your

Family and A part for yourself, love from the friends to

you Soloman Brown, H. Atkins, Was. Johnson, Mrs.

Brooks, Mr. Dykes. Mr. Smith is better at

presant. And do not forget to write the News of

Meakin's tryal. I cannot say any more at this

time; but remain yours and A true Friend ontell Death.

W. H. GILLIAM, the widow's Mite.

JAMES MERCER'S LETTER.

TORONTO, MARCH

17th, 1854.

MY

DEAR FRIEND

STILL:

- I take this method of informing you that I am well,

and when this comes to hand it may find you and your

family enjoying good health. Sir, my particular

for writing is that I wish to hear from you, and to hear

all the news from down South. I wish to know if

all things are working Right for the Rest of my

Bretheran whom in bondage. I will also Say that I

am very much please with Toronto, So also the friends

that came over with. It is true that we have not

been Employed as yet; but we are in hopes of be'en so in

a few days. We happen here in good time jest about

time the people in this country are going work. I

am in good health and good Spirits, and feeles Rejoiced

in the Lord for my liberty. I Received cople of

paper from you to-day. I wish you see James

Morris whom are Abram George the first and

second on the Ship Penn., give my respects to them, and

ask James if he will call at Henry W. Quarles

on May street oppisit the Jews synagogue and call for

Marena Mercer, give my love to her ask her of all

the times about Richmond, tell her to Send me all the

news. Tell Mr. Morris that there will be no

danger in going to that place. You will also tell

M. to make himself known to her as she may know who sent

him. And I wish to get a letter from you.

JAMES M. MERCER.

JOHN H. HILL'S LETTER.

MY

FRIEND, I would like to hear from

you, I have been looking for a letter from you for

Several days as the last was very interesting to me,

please to write Right away.

Yours most Respectfully,

JOHN

H. HILL.

Instead of

weeping over the sad situation of his "penniless"

mistress and showing any signs of contrition for having

wronged the man who had the mortgage of seven hundred

and fifty dollars on him, James actually "feels

rejoiced in the Lord for his liberty," and is "very much

pleased with

[Pg. 59]

Toronto;" but is not satisfied yet, he is even

concocting a plan by which his wife might be run off

from Richmond, which would be the cause of her owner (Henery

W. Quarles, Esq.) losing at least one thousand

dollars.

ST. CATHARINE,

CANADA, JUNE

8th, 1854

MR.

STILL, DEAR

FRIEND: - I received a letter from

the poor old widow, Mrs. L. E. White, and she

says I may come back if I choose and she will do a good

part by me. Yes, Yes I am choosing the western

side of the South for my home. She is smart, but

cannot bung my eye, so she shall have to die in the poor

house at least, so she says, and Mercer and

myself will be the cause of it. That is all right.

I am getting even with her now for I was in the poor

house for twenty-five years and have just got out.

And she said she knew I was coming away six weeks before

I started, so you may know my chance was slim. But

Mr. John Wright, said I came off like a gentleman

and he did not blame me for coming for I was a great

boy. Yes I here him enough he is all gas. I

am in Canada, and they cannot help themselves.

About that subject I will not say anything more.

You must write to me as soon as you can and let me here

the news and how the Family is and yourself. Let

me know how the times is with the U. G. R. R. Co.

Is it doing good business? Mr. Dykes sends

his respects to you. Give mine to your family.

Your true friend,

W. H. GILLIAM

John Clayton,

the companion is tribulation of William and James,

must not be lost sight of any longer. He was owned

by the Widow Clayton and was white enough to have

been nearly related to her, being a mulatto. He

was about thirty-five years of age, a man of fine

appearance, and quite intelligent. Several years

previous he had made an attempt to escape, but failed.

Prior to escaping in this instance, he had been laboring

in a tobacco factory at $150 a year. It is

needless to say that he did not approve of the "peculiar

institution." He left a wife and one child behind

to mourn after him. Of his views of Canada and

Freedom, the following frank and sensible letter, penned

shortly after his arrival, speaks for itself.

TORONTO, March

6th, 1854.

DEAR

MR. STILL:

- I take this method of informing you that I am well

both in health and mind. You may rest assured that

I fells myself a free man and do not fell as I did when

I was in Virginia thanks be to God I have no

master into Canada but I am my own man. I arrived

safe into Canada on friday last. I must request of

you to write a few lines to my wife and jest state to

her that her friend arrived safe into this glorious land

of liberty and I am well and she will make very short

her time in Virginia. tell her that I likes here

very well and hopes to like it better when I gets to

work I don't meane for you to write the same words that

are written above but I wish you give her a clear

understanding where I am and Shall Remain here untel She

comes or I hears from her.

Nothing more at present but remain yours most

respectfully,

JOHN

CLAYTON.

You will please to direct the to Petersburg Luenena

Johns or Clayton John is best.

[pg. 60]

CLARISSA DAVIS

Arrived in Male Attire

Clarissa

fled from Portsmouth, Va., in May, 1854, with two of her

brothers. Two months and a half before she

succeeded in getting off, Clarissa had made a

desperate effort but failed. The brothers

succeeded, but she was left. She had not given up

all hope of escape, however, and therefore sought "a

safe hiding-place until an opportunity might offer," by

which she could follow her brothers on the U. G. R. R.

Clarissa was owned by Mrs. Brown and

Mrs. Burkley, of Portsmouth, under whom she had

always served.

Of them she spoke favorably, saying that she "had not

been used as hard as many others were." At this

period, Clarissa was about twenty-two years of

age, of a bright brown complexion, with handsome

features, exceedingly respectful and modest, and

possessed all the characteristics of a well-bred young

lady. For one so little acquainted with books as

she was, the correctness of her speech was perfectly

astonishing.

For Clarissa and her two brothers a "reward of

one thousand dollars" was kept standing in the papers

for a length of time, as there (articles) were

considered very rare and valuable; the best that could

be produced in Virginia.

In the meanwhile the brothers had passed safely on to

New Bedford,,, but Clarissa remained secluded,

"waiting for the storm to subside." Keeping up

courage day by day, for seventy-five days, with the fear

of being detected and severely punished, and then sold,

after all her hopes and struggles required the faith of

a martyr. Time after time, when she hoped to

succeed in making her escape, ill luck seemed to

disappoint her, and nothing but intense suffering

appeared to be in store. Like many others, under

the crushing weight of oppression, she thought she

"should have to die" ere she tasted liberty. In

this state of mind, one day, word was conveyed to her

that the steamship, City of Richmond, had arrived from

Philadelphia, and that the steward on board (with whom

she was acquainted), had consented to secrete her this

trip, if she could manage to reach the ship safely,

which was to start the next day. This news to

Clarissa was both cheering and painful. She had

been "praying all the time while waiting," but now she

felt "that if it would only rain right hard the next

morning about three o'clock, to drive the police

officers off the street, then she could safely make her

way to the boat. Therefore she prayed anxiously

all that day that it would rain, "but no sign of rain

appeared till towards midnight." The prospect

looked horribly discouraging; but she prayed on, and at

the appointed hour (three o'clock - before day), the

rain descended in torrents. Dressed in male

attire, Clarissa left the miserable coop where

she had been almost without light or air for two and a

half months, and unmolested,

[pg. 61]

reached the boat safely, and was secreted in a box by

Wm. Bagnal, a clever young man who sincerely

sympathized with the slave, having a wife in slavery

himself; and by him she was safely delivered into the

hands of the Vigilance Committee.

Clarissa Davis here, by advice of the Committee,

dropped her old name, and was straightway christened "Mary

D. Armstead." Desiring to join her brothers

and a sister in New Bedford, she was duly furnished with

her U. G. R. R. passport and directed thitherward.

Her father, who was left behind when she got off, soon

after made his way on North, and joined his children.

He was too old and infirm probably to be worth anything,

and had been allowed to go free, or to purchase himself

for a mere nominal sum. Slaveholders would, on

some such occasions, show wonderful liberality in

letting their old slaves go free, when they could work

no more. After reaching New Bedford, Clarissa

manifested her gratitude in writing to her friends in

Philadelphia repeatedly, and evinced a very lively

interest in the U. G. R. R. The appended letter

indicates her sincere feelings of gratitude and deep

interest in the cause -

NEW BEDFORD, August 26, 1855

MR. STILL:

- I avail my self to write you thes few lines hopeing

they may find you and your family well as they leaves me

very well and all the family well except y father he

seams to be improving with his shoulder he has been

able to work a little. I received the papers I was

highly delighted to receive them I was very glad to hear

from you in the wheler case I was very glad

to hear that the persons ware safe I was

very sory to hear that mr Williamson

was put in prison but I know if the praying part of the

people will pray for him and if he will put his trust in

the lord he will brig him out more than conquer please

remember my Dear old farther and sisters and brothers to

your family kiss the children for me I hear that the

yellow fever is very bad down south now if the

underground railroad could have free course the emergent

would cross the river of gordan rapidly. I hope it

may continue to run and I hope the wheels of the Car may

be greesed with more substantial greese so they may run

over swiftly I would have wrote before but

circumstances would not permit me. Miss Sanders

and all the friends desired to be remembered to you and

your family I shall be pleased to hear from the

underground rail road often

Yours respectfully,

MARY D. ARMSTEAD.

ANTHONY

BLOW ALIAS HENRY LEVISON

Secreted Ten Months - Eight days on the

Steamship City of Richmond bound for Philadelphia

Arrived from

Norfolk, about the 1st of November, 1854. Ten

months before starting, Anthony had been closely

concealed. He belonged to the estate of Mrs.

Peters, a widow, who had been dead about one year

before his concealment.

On the settlement of his old mistress' estate, which