|

It

seems proper, before attempting to record

the achievements of the negro soldiers in

the war of the Rebellion, that we should

consider the state of public opinion

regarding the negroes at the outbreak of the

war; also, in connection therewith, to note

the rapid change that took place during the

early part of the struggle.

For some cause, unexplained in a general sense, the

white people in the Colonies and in the

States, came to entertain against the

colored races therein a prejudice, that

showed itself in a hostility to the latter's

enjoying equal civil and political rights

with themselves. Various reasons are

alleged for it, but the difficulty of really

solving the problem lies in the fact that

the early settlers in this country came

without prejudice against color. The

Negro, Egyptian, Arab, and other colored

races known to them, lived in European

countries, where no prejudice, on account of

color existed. How very strange then,

that a feeling antagonistic to the negroes

should become a prominent feature in the

character of the European emigrants to these

shores and their descendants. It has

been held by some writers that the American

prejudice against the negroes was occasioned

by their docility and unresenting spirit.

Surely no one acquainted with the Indian

will agree that he is docile or wanting in

spirit, yet occasion ally there is

manifested a prejudice against him; the

recruiting officers in Massachusetts refused

to enlist Indians, as well as negroes, in

regiments and companies made up of white

citizens, though members of both races,

could sometimes be found in white regiments.

During the

[Pg. 94]

rebellion of 1861-5, some Western regiments

had one or two negroes and Indians in them,

but there was no general enlistment of

either race in white regiments.* The

objection was on account of color, or, as

some writers claim, by the fact of the

races—negro and Indian†

—having been enslaved. Be the

cause what it may, a prejudice, strong,

unrelenting, barred the two races from

enjoying with the white race equal civil and

political rights in the United States.

So very strong had that prejudice grown

since the Revolution, enhanced it may be by

slavery and docility, that when the

rebellion of 1861 burst forth, a feeling

stronger than law, like a Chinese wall only

more impregnable, encircled the negro, and

formed a barrier betwixt him and the army.

Doubtless peace—a long peace—lent its aid

materially to this state of affairs.

Wealth, chiefly, was the dream of the

American from 1815 to 1860, nearly half a

century; a period in which the negro was

friendless, save in a few strong-minded,

iron-hearted men like John Brown in

Kansas. Wendell Philips in New England,

Charles Sumner in the United

States Senate, Horace Greeley

in New York and a few others, who dared, in

the face of strong public sentiment, to

plead his cause, even from a humane

platform. In many places he could not

ride in a street car that was not inscribed,

"Colored persons ride in this car."

The deck of a steamboat, the box cars of the

railroad, the pit of the theatre and the

gallery of the church, were the locations

accorded him. The church lent its

influence to the rancor and bitterness of a

prejudice as deadly as the sap of the Upas.

To describe public opinion respecting the negro a half

a century ago, is no easy task. It was just

budding into

*I arrived in New York in August, 1862. from

Valparaiso, Chili. on the steamship

"Bio-Bio," of Boston, and in company with

two Spaniards, neither of whom could speak

English, enlisted in a New York regiment.

We were sent to the rendezvous on one of the

islands in the harbor. The third day

after we arrived at the barracks. I

was sent with one of my companions to carry

water to the cook, an aged negro, who

immediately recognized me, and in such a way

as to attract the attention of the corporal,

who reported the matter to the commanding

officer, and before I could give the cook

the hint, he was examined by the officer of

the day. At noon I was accompanied by

a guard of honor to the launch, which landed

me in New York. I was a negro, that

was all; how it was accounted for on the

rolls I cannot say. I was honorably

discharged, however, without receiving a

certificate to that effect.

†The

Indians referred to are many of those

civilized and living as citizens In

the several .States of the Union.

[Pg. 95]

maturity when DeTocqueville visited the

United States, and, as a result of that

visit, he wrote, from observation, a pointed

criticism upon the manners and customs, and

the laws of the people of the United States.

For fear that I might be thought

over-doing—heightening—giving too much

coloring to the strength, and extent and

power of the prejudice against the negro I

quote from that distinguished writer, as he

clearly expressed himself under the heading,

"Present and Future condition of the

three races inhabiting the United States."

He said of the negro:

I see that in a certain portion of the

United States at the present day, the legal

barrier which separates the two races is

tending to fall away, but not that which

exists in the manners of the country.

Slavery recedes, but the prejudice to which

it has given birth remains stationary.

Whosoever has inhabited the United States,

must have perceived, that in those parts of

the United States, in which the negroes are

no longer slaves, they have in nowise drawn

nearer the whites; on the contrary,

the prejudice of the race appears to be

stronger in those States which have

abolished slavery, than in those where it

still exists. And, nowhere is it so

intolerant as in the states where servitude

has never been known. It is true, that

in the North of the Union, marriages may be

legally contracted between negroes and

whites, but public opinion would stigmatize

a man, who should content himself with a

negress, as infamous. If oppressed,

they may bring an action at law, but they

will find none but whites among their

judges, and although they may legally serve

as jurors, prejudice repulses them for that

office. In theatres gold cannot

procure a seat for the servile race beside

their former masters, in hospitals they lie

apart. They are allowed to invoke; the

same divinity as the whites. The gates

of heaven are not closed against those

unhappy beings; but their inferiority is

continued to the very confines of the other

world. The negro is free, but he can

share, neither the rights, nor the labor,

nor the afflictions of him, whose equal he

has been declared to be, and he cannot meet

him upon fair terms in life or death."

DeTocqueville, as is seen, wrote with much bitterness

and sarcasm, and, it is but fair to state,

makes no alluusion

to any exceptions to the various conditions

of affairs that he mentions. In all

cases matters might not have been exactly as

bad as he pictures them, but as far as the

deep-seated prejudice against the negroes,

and indifference to their rights and

elevation are concerned, the facts will

freely sustain the views so forcibly

presented.

The negro had no remembrance of the country of his

[Pg. 96]

ancestry, Africa, and he abjured their

religion. In the South he had no

family; women were merely the temporary

sharer of his pleasures; his master's cabins

were the homes of his children during their

childhood. While the Indian perished

in the struggle for the preservation of his

home, his hunting grounds and his freedom,

the negro entered into slavery as soon as he

was born, in fact was often purchased in the

womb, and was born to know, first, that he

was a slave. If one became free, he

found freedom harder to bear than slavery;

half civilized, deprived of nearly all

rights, in contact with his superiors in

wealth and knowledge, exposed to the rigor

of a tyrannical prejudice moulded into laws,

he contented himself to be allowed to live.

The Negro race, however, it must be remembered, is the

only race that has ever come in contact with

the European race, and been able to

withstand its atrocities and oppression; all

others, like the Indian, whom they could not

make subservient to their use, they have

destroyed. The Negro race, like the

Israelites, multiplied so rapidly in

bondage, that the oppressor became alarmed,

and began discussing methods of safety to

himself. The only people able to cope

with the Anglo-American or Saxon, with any

show of success, must be of patient

fortitude, progressive intelligence, brave

in resentment and earnest in endeavor.

In spite of his surroundings and state of public

opinion the African lived, and gave birth,

largely through amalgamation with the

representatives of the different races that

inhabited the United States, to a new

race,—the American Negro.

Professor Sampson in his mixed races says:

"The Negro is a now race, and is not the

direct descent of any people that have ever

flourished. The glory of the negro

race is yet to come."

As evidence of its capacity to acquire glory, the

record made in the late struggle furnishes

abundant proof. At the sound of the

tocsin at the North, negro waiter, cook,

barber, boot-black, groom, porter and

laborer stood ready at the enlisting office;

and though the recruiting officer refused to

list his name, he waited like the "patient

ox" for the partition-prejudice-to be

removed. He waited

[Pg. 97]

ROBERT SMALLS, (pilot).

WILLIAM MORRISON, (sailor), A. GRADINE,

(Engineer),

JOHN SMALLS, (sailor).

Four of the crew who. while the white

officers were ashore in Charleston. S. C.

ran off with the Confederate war steamer.

" Planter," passed Fort Sumter and delivered

the vessel to the United States authorities.

On account of the during exploit a special

act of Congress was passed ordering one-half

the value of the captured vessel to be

invested in V. S. bonds, and the interest

thereof to be annually paid them or their

heirs. Robert Small- joined the Union

army, and after the war became active and

prominent in politics.

[Pg. 98]

two years before even the door of the

partition was opened; then he did not

hesitate, but walked in, and with what

effect the world knows.

The war cloud of 1860 still more aroused the bitter

prejudice against the negro at both the

North and South; but he was safer in South

Carolina than in New York, in Richmond than

in Boston.

It is a natural consequence, when war is waged between

two nations, for those on either side to

forget local feuds and unite against the

common enemy, as was done in the

Revolutionary war. How different was

the situation now when the threatened war

was not one between nations, but between

states of the same nation. The feeling

of hostility toward the negro was not put

aside and forgotten as other troublesome

matters were, but the bitterness became

intensified and more marked.

The Confederate Government though organized for the

perpetual enslavement of the negro, fostered

the idea that the docility of the negroes

would allow them to be used for any purpose,

without their having the least idea of

becoming freemen. Some idea may be

formed of public opinion at the South at the

beginning of the war by what Mr.

Pollard, in his history, gives as the

feeling at the South at the close of the

second year of the struggle:

"Indeed, the war had

shown the system of slavery in the South to

the world in some new and striking aspects,

and had removed much of that cloud of

prejudice, defamation, falsehood, romance

and perverse sentimentalism through which

our peculiar institution had been formerly

known to Europe. It had given a better

vindication of our system of

slavery than all the books that could be

written in a generation. It had shown

that slavery was an element of strength to

us; that it had assisted us in our struggle;

that no servile insurrections had taken

place in the South, in spite of the

allurements of our enemy; that the slave had

tilled the soil while his master had fought;

that in large districts, unprotected by our

troops, and with a white population,

consisting almost exclusively of women and

children, the slave had continued his work,

quiet, faithful, and cheerful; and that, as

a conservative element in our social system,

the institution of slavery had withstood the

shocks of war, and been a faithful ally of

our army, although instigated to revolution

by every art of the enemy, and prompted to

the work of assassination and pillage by the

most brutal examples of the Yankee

soldiers."

[Pg. 99] - BLANK

[Pg. 100]

With this view, the whole slave population

was brought to the assistance of the

Confederate Government, and thereby caught

the very first hope of freedom. An

innate reasoning taught the negro that

slaves could not be relied upon to fight for

their own enslavement. To get to the

breastworks was but to get a chance to run

to the Yankees; and thousands of those whose

elastic step kept time with the martial

strains of the drum and fife, as they

marched on through city and town, enroute to

the front, were not elated with the hope of

Southern success, but were buoyant with the

prospects of reaching the North.

The confederates found it no easy task to

watch the negroes and the Yankees too; their

attention could be given to

but one at a time; as a slave expressed it,

"when marsa watch the Yankee, nigger go;

when marsa watch the nigger, Yankee come."

But the Yankees did not always receive him

kindly during the first year of the war.

In his first inaugural, Mr. Lincoln declared

"that the property, peace and security of no

section are to be in anywise endangered by

the new incoming administration.." The

Union generals, except Fremont and

Phelps and a few subordinates, accepted

this as public opinion, and as their guide

in dealing with the slavery question.

That opinion is better expressed in the

doggerel, sung in after months by the negro

troops as they marched along through Dixie:

"McClellan

went to Richmond with two hundred thousand

braves,

He said, 'keep buck the niggers and the Union he would

save."

Little Mac, he had his way, still the Union is in

tears,

And they call for the help of the colored volunteers."

The first two lines expressed the sentiment at the

time, not only of the Army of the Potomoc,

but the army commanders everywhere, with the

exceptions named. The

administration winked at the enforcement of

the fugitive slave bill by the soldiers

engaged in capturing and returning the

negroes coming into the Union lines.*

Undoubted ly it was the idea of the

Government to turn the course of the war

from its rightful channel, or in other

words,—in

* See Appendix. "A."

[Pg. 101] - BLANK

[Pg. 102]

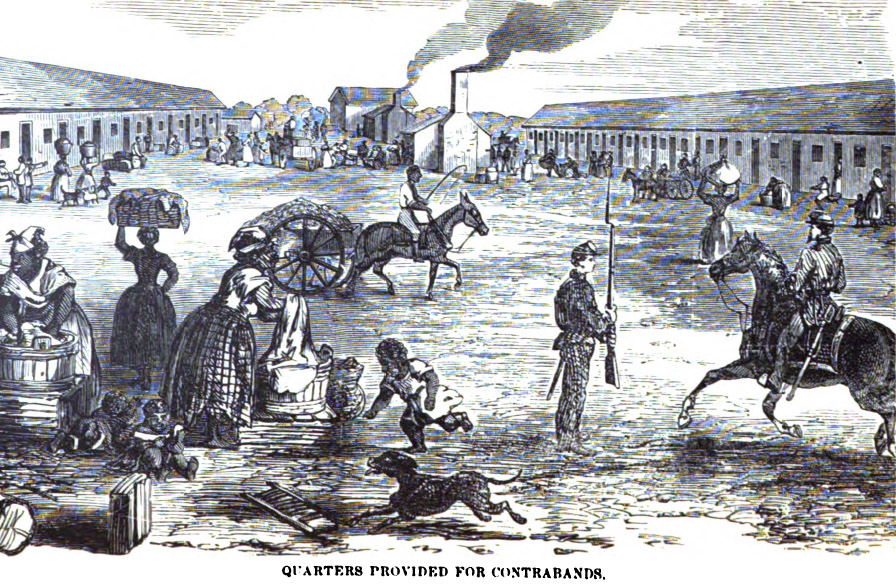

QUARTERS PROVIDED FOR CONTRABANDS.

[Pg. 103]

the restoration of the Union,—to eliminate

the anti-slavery sentiment, which demanded

the freedom of the slaves.

Hon. Elisha R. Potter, of Rhode Island,—"who

may," said Mr. Greeley, "be fairly

styled the hereditary chief of the

Democratic party of that State,"—made a

speech on the war in the State Senate, on

the 10th of August 1861, in which he

remarked:

I have said that the war may

assume another aspect, and be a short and

bloody one. And to such a war—an

anti-slavery nap—it seems to me we are

inevitably drifting. It seems to me

hardly in the power of human wisdom to

prevent it. We may commence the war

without meaning to interfere with slavery;

but let us have one or two battles, and get

our blood excited, and we shall not only not

restore any more slaves, but shall proclaim

freedom wherever we go. And it seems

to me almost judicial blindness on the part

of the South that they do not see that this

must be the inevitable result, if the

contest is prolonged."

This sentiment became bolder daily as the

thinking Union men viewed the army turning

aside from its legitimate purposes, to catch

runaway negroes, and return them.

Party lines were also giving away; men in

the army began to realize the worth of the

negroes as they sallied up to the rebel

breastworks that were often impregnable.

They began to complain, finding the negro

with his pick and spade, a greater

hinderance to their progress than the cannon

balls of the enemy ; and more than one said

to the confederates, when the pickets of the

two armies picnicked together in the

battle's lull, as frequently they did: "We

can whip you, if you keep your negroes out

of your army."

Quite a different course was pursued in the navy.

Negroes were readily accepted all along the

coast on board the war vessels, it being no

departure from the regular and established

practice in the service. The view with

which the loyal friends of the Union began

to look at the negro and the rebellion, was

aptly illustrated in an article in the

Montgomery (Ala.) Advertiser in 1801,

which said:

"The Slaves as a MILITARY ELEMENT IN THE

SOUTH.—The total white population of the

eleven States now comprising the Confederacy

is 6,000,000, and, therefore, to fill up the

ranks of the proposed army (600,000) about

ten per cent of the entire white population

will be

[Pg. 104]

required. In any other country than our own

such a draft could not be met, but the

Southern States can furnish that number of

men, and still not leave the material

interests of the country in a suffering

condition. Those who are incapacitated

for bearing arms can oversee the

plantations, and the negroes can go on

undisturbed in their usual labors. In

the North the case is different; the men who

join the army of subjugation are the

laborers, the producers, and the factory

operatives. Nearly every man from that

section, especially those from the rural

districts, leaves some branch of industry to

suffer during his absence. The

institution of slavery in the South alone

enables her to place in the field a force

much larger in proportion to her white

population than the North, or indeed any

country which is dependent entirely on free

labor. The institution is a tower of

strength to the South, particularly at the

present crisis, and our enemies will be

likely to find that the 'moral cancer' about

which their orators are so fond of prating,

is really one of the most effective weapons

employed against the Union by the South.

Whatever number of men may be needed for

this war, we are confident our people stand

ready to furnish. We are all enlisted

for the war, and there must be no holding

back until. the independence of the South is

fully acknowledged."

The

facts already noted became apparent to the

nation very soon, and then came a, change of

procedure, and the war began to be

prosecuted upon quite a different policy.

Gen. McClellan, whose loyalty

to the new policy was doubted, was removed

from the command of the Army of

the Potomac, and slave catching ceased.

The XXXVII Congress convened in Dec. 1861,

in its second session, and passed the

following additional article of war:

"All officers are prohibited from employing

any of the forces under their respective

commands for the purpose of returning

fugitives from service or labor who may have

escaped from any persons to whom such

service or labor is claimed to be due. Any

officer who shall be found guilty by

courtrmartial of violating this article

shall be dismissed from the service."

This was the initatory measure of the new

policy, which progressed to its fulfillment

rapidly. And then what Mr.

Cameron, Secretary of War, had

recommended in December. 1861, and to which

the President objected, very soon developed,

through a series of enactments, in the

arming of the negro; in which the loyal

people of the whole country acquiesced, save

the border states people, who fiercely

opposed it as is shown in the conduct of

Mr.

[Pg. 105]

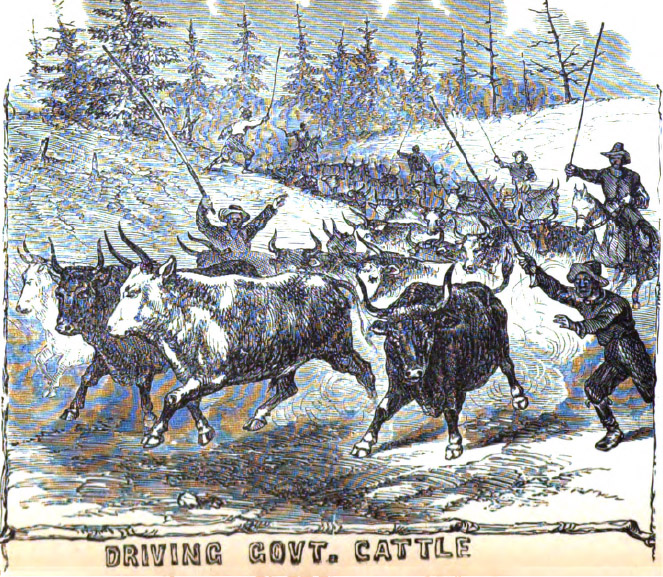

DRIVING GOV'T. CATTLE

[Pg. 106] - BLANK

[Pg. 107]

Wickliffe, of Kentucky; Salisbury, of

Delaware, and others in Congress.

Public opinion was now changed, Congress had prohibited

the surrender of negroes to the rebels, the

President issued his Emancipation

Proclamation, and more than 150,000 negroes

were fighting for the Union. The

Republican party met in convention at

Chicago, and nominated Mr. Lincoln

for the second term as President of the

United States; the course of his first

administration was now to be approved or

rejected by the people. In the

resolutions adopted, the fifth one of them

related to Emancipation and the negro

soldiers. It was endorsed by a very

large majority of the voters. A writer

in one of the magazines, prior to the

election, thus reviews the resolutions:

"The fifth resolution commits us to the

approval of two measures that have aroused

the most various and strenuous opposition,

the

Proclamation of Emancipation and the use of

negro troops. In reference to the

first, it is to be remembered that it is a

war measure. The express

language of it is: 'By virtue of the

power in me vested as commander-in-chief of

the army and navy of the United States in

time of actual armed rebellion against the

authority and Government of the United

States, and as a fit and necessary war

measure for suppressing said rebellion.'

Considered thus, the Proclamation is not

merely defensible, but it is more; it is a

proper and efficient means of weakening the

rebellion which every person desiring its

speedy overthrow must zealously and perforce

uphold. Whether it is of any legal

effect beyond the actual limits of our

military lines, is a question that need not

agitate us. In due time the supreme

tribunal of the nation will be called to

determine that, and to its decision the

country will yield with all respect and

loyalty. But in the mean time let the

Proclamation go wherever the army goes, let

it go wherever the navy secures a foothold

on the outer border of the rebel territory,

and let it summon to our aid the negroes who

are truer to the Union than their disloyal

masters; and when they have come to us and

put their lives in our keeping, let us

protect and defend them with the whole power

of the nation. Is there any thing

unconstitutional in that? Thank God,

there is not. And he who is willing to

give back to slavery a single person who has

heard the

summons and come within our lines to obtain

his freedom, he who would give up a single

man, woman, or child, once thus actually

freed, is

not worthy the name of American. He

may call himself Confederate, if he will.

"Let it be remembered, also that the Proclamation has

had a very

[Pg. 108]

important bearing upon our

foreign relations. It evoked in behalf

of 6ur country that sympathy on the part of

the people in Europe, whose is the only

sympathy we can ever expect in our struggle

to perpetuate free institutions.

Possessing that sympathy, moreover, we have

had an element in our favor which has kept

the rulers of Europe in wholesome dread of

interference. The Proclamation

relieved us from the false position before

attributed to uh of fighting simply for

national power. It placed uh right in

the eyes of the world, and transferred men's

sympathies from a confederacy fighting for

independence as a means of establishing

slavery, to a nation whose institutions mean

constitutional liberty, and, when fairly

wrought out, must end in universal freedom."

The

change of policy and of public opinion was

be strongly endorsed that it affected the

rebels, who shortly passed a Congressional

measure for arming 200.000 negroes

themselves. What a reversal of things;

what a change of sentiment, in less than

twenty-four months!* Mr.

Lincoln, in justifying the change, is

reported to have said to Judge

Mills, of Wisconsin:

"The slightest knowledge of arithmetic will

prove to any man that the rebel armies

cannot be destroyed with Democratic

strategy. It would sacrifice all the

white men of the North to do it. There

are now in the service of the United States

near two hundred thousand able bodied

colored men, most of them under arms,

defending and acquiring Union territory.

The Democratic strategy demands that these

forces be disbanded, and that the masters be

conciliated by restoring them to slavery.

The black men who now assist Union prisoners

to escape, they are to be converted into our

enemies in the vain hope of gaining the good

will of their masters. We shall have

to fight two nations instead of one.

You cannot conciliate the South if you

guarantee to them ultimate success; and the

experience of the present war proves their

success is inevitable if you fling the

compulsory labor of millions of black men

into their side of the scale. Will you

give our enemies such military advantages as

insure success, and then depend on coaxing,

flattery, and concession to get them back

into the Union? Abandon all the posts

now garrisoned by black men; take two

hundred thousand men from

our side and put them in the battlefield or

cornfield against us, and we would be

compelled to abandon the war in three weeks.

We have to hold territory in inclement and

sickly places; where are the Demo-

---------------

*

"Those who have declaimed loudest against

the employment of negro troops have shown a

lamentable amount of ignorance, and an

equally lamentable lack of common sense.

They know as little of the military history

and martial qualities of the African race as

they do of their own duties as commanders.

All distinguished generals of modern times who have had

opportunity to use negro soldiers, have

uniformly applauded their subordination,

bravery, and powers of endurance.

Washington solicited the military

services of negroes in the revolution, and

rewarded them. Jackson did the

same in the war of 1812. Under both those

great captains, the negro troops fought so

well that they 'received unstinted praise."—Charles

Sumner

[Pg. 109]

crats to do this? It

was a free fight, and the field was open to

the war Democrats to put down this rebellion

by fighting against both master' and slave,

long before the present policy was

inaugurated. There have been men base

enough to propose to me to return to slavery

the black warriors of Port Hudson and

Olustee, and thus win the respect of the

masters they fought. Should I do so, I

should deserve to be dammed in time and

eternity. Come what will, I will keep

my faith with friend and foe. My

enemies pretend I am now currying on this

war for the sole purpose of abolition.

So long as I am President, it shall be

carried on for the sole purpose of restoring

the Union. But no human power can

subdue this rebellion without the use of the

emancipation policy, and every other policy

calculated to weaken the moral and physical

forces of the rebellion. Freedom has

given us two hundred thousand men raised on

southern soil. It will give us more

yet. Just so much it has subtracted

from the enemy; and instead of alienating

the South, there are now evidences of a

fraternal feeling growing up between our men

and the rank and file of the rebel soldiers.

Let my enemies prove to the country that the

destruction of slavery is not necessary to

the restoration of the Union. I will

abide the issue."

But

the change of policy did not change the

opinion of the Southerners, who,

notwithstanding the use which the

Confederate Government was making of the

negro,still regarded him, in the United

States uniform, as a vicious brute, to be

shot at sight. I prefer, in closing

this chapter, to give the Southern opinion

of the negro, in the words of a

distinguished native of that section.

Mr. George W. Cable, in his "Silent

South," thus gives it:

"He was brought to our shores a naked,

brutish, unclean, captive, pagan savage, to

be and remain a kind of connecting link

between man and the beasts of burden.

The great changes to result from his contact

with a superb race of masters were not taken

into account. As a social factor he

was intended to be as purely zero as the

brute at the other end of his plow line.

The occasional mingling of his blood with

that of the white man worked no change in

the sentiment; one, two, four, eight,

multiplied upon or divided in to zero, still

gave zero for the result. Generafions

of American nativity made no difference; his

children and childrens' children were born

in sight of our door, yet the old notion

held fast. He increased to vast

numbers, but it never wavered. He

accepted our dress, language, religion, all

the fundamentals of our civilization, and

became forever expatriated from his own land

; still he remained, to us, an alien.

Our sentiment went blind. It did not

see that gradually, here by force and there

by choice, he was fulfilling a host of

conditions that earned at least a solemn

moral right to that naturalization which

soonest first had dreamed of giving him.

Frequently be even bought

[Pg. 110]

back the freedom of which he

had been robbed, became a tax-payer, and at

times an educator of his children at his own

expense; but the old idea

of alienism passed laws to banish him, his

wife, and children by thousands from the

State, and threw him into loathsome jails as

a common felon for returning to his native

land. It will be wise to remember that

these were the acts of un enlightened, God

fearing people."

SCENE IN AND NEAR A RECRUITING OFFICE

|