|

The

BLACK PHALANX;

A History of the

NEGRO SOLDIERS OF THE UNITED STATES

in the Wars of

1775-1812, 1861-'65,

By

Joseph T. Wilson

Late of the 2nd Reg't. La. Native Guard Vols. 54th Mass. Vols.

Aide-De-camp to the Commander-In-Chief G. A. R.

Author of

"Emancipation," "Voice of a New Race," "Twenty-Two Years of

Freedom," etc., etc.

-----

56 Illustrations

-----

Hartford, Conn.:

American Publishing Company

1890

PT II.

CHAPTER V. -

DEPARTMENT of the GULF

pg. 183

When Admiral Farragut's fleet

anchored at New Orleans, and Butler occupied

the city, three regiments of confederate

negro troops were under arms guarding the

United States Mint building, with orders to

destroy it before surrendering it to the

Yankees. The brigade, however, was in

command of a Creole mulatto, who, instead of

carrying out the orders given him, and

following the troops out of the city on

their retreat, counter-marched his command

and was cut off from the main body of the

army by the Federal forces, to whom they

quietly surrendered a few days after.

General Phelps commanded the Federal

forces at Carrolton, about seven miles from

New Orleans, the principal point in the

cordon around the city. Here the

slaves congregated in large numbers, seeking

freedom and protection from their barbarous

overseers and masters. Some of these

poor creatures wore irons and chains; some

came bleeding from gun-shot wounds.

General Phelps was an old

abolitionist, and had early conceived the

idea that the proper thing to do was for the

government to arm the negroes. Now

came his opportunity to act. Hundreds of

able-bodied men were in his camps, ready and

willing to fight for their freedom and the

preservation of the Union. The

secessionists in that neighborhood

complained to General Butler

about their negroes leaving them and going

into camp with the Yankees. So

numerous were the complaints, that the

General, acting under orders from

Washington, and also foreseeing that

[Pg. 184] -

General Phelps

intended allowing the slaves to gather at his

post, issued the following order:

"NEW ORLEANS,

May 23, 1862.

"GENERAL: - You will cause all

unemployed persons, black and white, to be excluded from your lines.

"You will not permit either black or white persons to

pass your lines, not officers and soldiers or

belonging to the navy of the United States,

without a pass from these head-quarters, except

they are brought in under guard as captured

persons, with information, and those to be

examined and detained as prisoners of war, if

they have been in arms against the United

States, or dismissed and sent away at once, as

the case may be. This does not apply to

boats passing up the river without landing

within the lines.

"Provision dealers and marketmen are to be allowed to

pass in with provisions and their wares, but not

to remain over night.

"Persons having had their permanent residence within

your lines before the occupation of our troops,

are not to be considered unemployed persons.

"Your officers have reported a large number of

servants. Every officer so reported

employing servants will have the allowance for

servants deducted from his pay-roll.

Respectfully, your obedient

servant,

B. F. BUTLER

"Brig. -Gen.

PHELPS, Commanding Camp Parapet."

This struck Gen. Phelps as an inhuman

order, though he obeyed it and placed the slaves

just outside of his camp lines. Here the

solders, having drank in the spirit of their

commander, cared for the fugitives from slavery.

But they continued to come, according to devine

appointment, and their increase prompted Gen.

Phelpsto write this patriotic, pathetic and

eloquent appeal, knowing it must reach the

President:

"CAMP

PARAPET, NEAR

CARROLLTON, LA.,

June 16, 1862.

"Capt. R. S. DAVIS, Acting Assistant

Adjutant-General, New Orleans, La.:

"SIR: I enclose herewith, for the information of

the major-general commanding the department, a

report of Major Peck, officer of

the day, concerning a large number of negroes,

of both sexes and all ages, who are lying near

our pickets, with bag and baggage, as if they

had already commenced an exodus. Many of

these negroes have been sent away from one of

the neighboring sugar plantations by their

owner, a Mr. Babilliard La Blanche, who

tells them, I am informed, that 'the Yankees are

king here now, and that they must go to their

king for food and shelter.'

"They are of that four millions of our colored subjects

who have no king or chief, nor in fact any

government that can secure to them the simplest

natural rights. They can not even be

entered into treaty stipulations with and

deported to the east, as our Indian tribes have

been to the west. They have no right to

the mediation of a justice of the peace or jury

between them and chains and lashes. They

have no right to wages for their labor; no right

to the Sabbath; no right to the institution of

marriage; no right to letters or to

self-defense. A small class of owners,

rendered unfeeling, and even unconscious and

unreflecting by habit, and a large part of them

ignorant and vicious, stand between them and

their government, destroying its sovereignty.

This government has not the power even to

regulate the number of lashes that its subjects

may receive. It can not say that they

shall receive thirty-nine instead of forty.

To a large and growing class of its subjects it

can secure neither justice, moderation, nor the

advantages of Christian religion; and if it can

not protect all its subjects, it can

protect none, either black or white.

"It is nearly a hundred years since our people first

declared to the nations of the world that all

men are born free; and still we have not made

our declaration good. Highly revolutionary

measures have since then been adopted by the

admission of Missouri and the annexation of

Texas in favor of slavery by the barest

majorities of votes, while the highly

conservative vote of two-thirds has at length

been attained against slavery, and still slavery

exists - even, moreover, although two-thirds of

the blood in the veins of our slaves is fast

becoming from our own race. If we wait for

a larger vote, or until our slaves' blood

becomes more consanguined still with our own,

the danger of a violent revolution, over which

we can have no control, must become more

imminent every day. By a course of

undecided action, determined by no policy but

the vague will of a war-distracted people, we

run the risk of precipitating that very

revolutionary violence which we seem seeking to

avoid.

"Let us regard for a moment the elements of such a

revolution.

"Many of the slaves here have been sold away from the

border States as a punishment, being too

refractory to be dealt with there in the face of

the civilization of the North. They come

here with the knowledge of the Christian

religion, with its germs planted and expanding,

as it were, in the dark, rich soil of their

African nature, with feel-

[Pg. 185] -

Washing in Camp

[Pg. 186] - BLANK

[Pg. 187]

ings of relationship with the families from

which they came, and with a sense of unmerited

banishment as culprits, all which tends to bring

upon them a greater severity of treatment and a

corresponding disinclination 'to receive

punishment'. They are far superior beings

to their ancestors, who were brought from Africa

two generations ago, and who occasionally

rebelled against comparatively less severe

punishment than is inflicted now. While

rising in the scale of Christian beings, their

treatment is being rendered more severe than

ever. The whip, the chains, the stocks,

and imprisonment are no mere fancies here; they

are used to any extent to which the imagination

of civilized man may reach. Many of them

are as intelligent as their masters, and far

more moral, for while the slave appeals to the

moral law as his vindication, clinging to it as

to the very horns of the alter of his safety and

his hope, the master seldom hesitates to wrest

him from it with violence and contempt.

The slave, it is true, bears o resentment; he

asks for no punishment for his master; he simply

claims justice for himself; and it is this

feature of his condition that promises more

terror to the retribution when it comes.

Even now the whites stand accursed by their

oppression of humanity, being subject to a

degree of confusion, chaos, and enslavement to

error and wrong, which northern society could

not credit or comprehend.

"Added to the four millions of the colored race whose

disaffection is increasing even more rapidly

than their number, there are at least four

millions more of the white race whose growing

miseries will naturally seek companionship with

those of the blacks. This latter portion

of southern society has its representatives, who

swing from the scaffold with the same desperate

coolness, though from a directly different

cause, as that which was manifested by John

Brown. The trator Muford, who

swung the other day for trampling on the

national flag, had been rendered placid and

indifferent in his desperation by a government

that either could not or would not secure to its

subjects the blessings of liberty which that

flag imports. The South cries for justice

from the government as well as the North,

through in a proud and resentful spirit; and in

what manner is that justice to be obtained?

Is it to be secured by that wretched resource of

a set of profligate politicians, called

'reconstruction?' No, it is to be obtained

by the abolition of slavery, and by no other

course.

"it is vain to deny that the slave system of labor is

giving shape to the government of the society

where it exists, and that that government is not

republican, either in form or spirit. It

was through this system that the leading

conspirators have sought to fasten upon the

people an aristocracy or a despotism; and it is

not sufficient that they should be merely

defeated in their object, and the country be rid

of their rebellion; for by our constitution we

are imperatively obliged to sustain the State

against the ambition of unprincipled leaders,

and secure to them the republican form of

government. We have positive duties to

perform, and should hence adopt and pursue a

positive, decided policy. We have services

to render to certain states which they cannot

perform for themselves. We are in an

emergency which the framers of the constitution

might easily have foreseen, and for which they

have amply provided.

"It is clear that the public good requires slavery to

be abolished; but in what manner is it to be

done? The mere quiet operation of

congressional law can not deal with slavery as

in its former status before the war, because the

spirit of law is right reason, and there is no

reason in slavery. A system so

unreasonable as slavery can not be regulated by

reason. We can hardly expect the several

states to adopt laws or measures against their

own immediate interests. We have seen that

they will rather find arguments for crime than

seek measures for abolishing or modifying

slavery. But there is one principle which

is fully recognized as a necessity in conditions

like ours, and that is that the public safety is

the supreme law of the State, and that amid the

clash of arms the laws of peace are silent.

It is then for our president, the

commander-in-chief of our armies, to declare the

abolition of slavery, leaving it to the wisdom

of congress to adopt measures to meet the

consequences. This is the usual course

pursued by a general or by a military power.

That power gives orders affecting complicated

interests and millions of property, leaving it

to the other functions of government to adjust

and regulate the effects produced. Let the

president abolish slavery, and it would be an

easy matter for congress, through a

well-regulated system of apprenticeship, to

adopt safe measures for effecting a gradual

transition from slavery to freedom.

"The existing system of labor in Louisiana is unsuited

to the age; and by the intrusion of the national

forces it seems falling to pieces. It is a

system of mutual jealousy and suspicion between

the master and the man - a system of violence,

immorality and vice. The fugitive negro

tells us that our presence renders his condition

worse with his master than it was before, and

that we offer no alleviation in return.

The system is impolitic, because it offers but

one stimulent to labor and effort, viz.:

the lash, when another, viz.: money, might be

added with good effect. Fear, and the

other low and bad qualities of the slave, are

appealed to, but never the good. the

relation, therefore, between capital and labor,

which ought to be generous and confiding, is

darkling, suspicious, unkindly, full of

reproachful threats, and without concord or

peace. This condition of things

renders the interests of society a prey to

politicians. Politics ceased to be

practical or useful.

"The questions that ought to have been discussed in the

late extraordinary convention of Louisiana, are:

First, What ought the State of Louisiana

to do to adopt her ancient system of labor to

the present advanced spirit of the age?

And Second, How can a State be assisted

by the general government in effecting the

change? But instead of this, the only

question before that body was how to vindicate

slavery by flogging the Yankees!

"Compromises hereafter are not to be made with

politicians, but with sturdy labor and the right

to work. The interests of workingmen

resent political trifling. Our political

education, shaped almost entirely to the

interest of slavery, ahs been false and vicious

in the extreme, and it must be corrected with as

much suddenness, almost, as that with which

Salem witchcraft came to an end. The only

question that remains to decide is how the

change shall take place.

"We are not without examples and precedents in the

history of the past. The enfranchisement

of the people of Europe has been, and is still

going on, through the instrumentality of

military service; and by this means our slaves

might be raised in the

[Pg. 188] -

scale of civilization and

prepared for freedom. Fifty regiments

might be raised among them at once, which could

be employed in this climate to preserve order,

and thus prevent the necessity of retrenching

our liberties, as we should do by a large army

exclusively of whites. For it is evident

that a considerable army of whites would give

stringency to our government, while an army,

partly of blacks, would naturally operate in

favor of freedom and against those influences

which at present most endanger our liberties.

At the end of five years they could be sent to

Africa and their places filled with new

enlistments.

"There is no practical evidence against the efforts of

immediate abolition, even if there is not in its

favor. I have witnessed the sudden

abolition of flogging at will in the army and of

legalized flogging at will in the army and of

legalized flogging in the navy against the

prejudice-warped judgments of both, and, from

the beneficial effects there, I have nothing to

fear from the immediate abolition of slavery.

I fear, rather, the violent consequences from a

continuance of the evil. But should such

an act devastate the whole State of Louisiana,

and render the whole soil here but the mere

passage-way of the fruits of the enterprise and

industry of the Northwest, it would be better

for the country at large than it is now as the

seat of disaffection and rebellion.

"When it is remembered that not a word is found in our

constitution sanctioning the buying and selling

of human beings, a shameless act which renders

our country the disgrace of Christendom, and

worse, in this respect, even than Africa

herself, we should have less dread of seeing the

degrading traffic stopped at once and forever.

Half wages are already virtually paid for slave

labor in the system of tasks which, in an

unwilling spirit of compromise, most of the

slave states have already been compelled to

adopt. At the end of five years of

apprenticeship, or of fifteen at farthest, full

wages could be paid to the enfranchised negro

race, to the double advantage of both master and

man. This is just; for we now hold the

slaves of Louisiana by the same tenure that the

State can alone claim them, viz.: by the

original right of conquest. We have so far

conquered them that a proclmation setting

them free, coupled with offers of protection,

would ddevastate every plantation in the State.

"In conclusion, I may state that Mr. La Blanche

is, as I am informed, a descendant from one of

the oldest families of Louisiana. He is

wealthy and a man of standing, and his act in

sending away his negroes to our lines, with

their clothes and furniture, appears to indicate

the convictions of his own mind as to the proper

logical consequences an deductions that should

follow from the present relative status of the

two contending parties. He seems to be

convinced that the proper result of the conflict

is the manumission of the slave, and he may be

safely regarded in this respect as a

representative man of the State. I so

regard him myself, and thus do I interpret his

action, although my camp now contains some of

the highest symbols of secessionism, which have

been taken by a party of the Seventh Vermont

volunteers from his residence.

"Meantime his slaves, old and young condition.

Driven away by their master, with threats of

violence if they return, and with no decided

welcome or reception from us, what is to be

their lot? Considerations of humanity are

pressing for an immediate solution of their

difficulties; and they are but a small portion

of their race who have sought and are still

seeking our pickets and our military stations,

declaring that they can not and will not any

longer serve their masters, and that all they

want is work and protection from us. In

such a state of things, the question occurs as

to my own action in the case. I cannot

return them to their masters, who not

unfrequently come in search of them, for I am,

fortunately, prohibited by an article of war

from doing that, even if my own nature did not

revolt at it. I can not receive them, for

I have neither work, shelter, nor the means or

plan of transporting them to Hayti, or of making

suitable arrangements with their masters until

they can be provided for.

"It is evident that some plan, some policy, or some

system is necessary on the part of the

government, without which the agent can do

nothing, and all his efforts are rendered

useless and of no effect. This is no new

condition in which I find myself; it is my

experience during the some twenty-five years of

my public life as a military officer of the

government. The new article of war

recently adopted my congress, rendering it

criminal in an officer of the army to return

fugitives from injustice, is the first support

that I have ever felt from the government in

contending against those slave influences which

are opposed to its character and to its

interests. But the more refusal to return

fugitives does not now meet the case. A

public agent in the present emergency must be

invested with wider and more positive powers

than this, or his services will prove as

valueless to the country as they are

unsatisfactory to himself.

"Desiring this communication to be laid before the

president, and leaving my commission at his

disposal, I have the honor to remain, sir.

"Very

respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. W. PHELPS,

Brigadier-General.

On the day on which he received this letter,

Gen. Butler forwarded to Washington this

dispatch:

"NEW

ORLEANS, LA.,

JUNE 18, 1862

"Hon.

E. M. STANTON, Secretary of War:

"SIR: - Since my last dispatch was written, I have

received the accompanying report from General

Phelps.

"It is not my duty

to enter into a discussion of the questions

which it presents.

"I desire, however, to state the information of Mr.

La Blanche, given me by his friends and

neighbors, and also Jack La Blanche,

his slave, who seems to be the leader of this

party of negroes. Mr. La BlancheI

have not seen. He, however, claims to be

loyal, and to have taken no part in the war, but

to have lived quietly on

[Pg. 189] - BLANK

[Pg. 190]

Cooking in Camp

[Pg. 191] -

his

plantation, some twelve miles above New Orleans,

on the opposite side of the river. He has

a son in the succession army, whose uniform and

equipments, &c., are the symbols of sucession

of which General Phelps speaks.

Mr. La Blanche's house was searched by order

of General Phelps, for arms and

contraband of war, and his neighbors say that

his negroes were told that they were free if

they would come to the general's camp.

"That thereupon the negroes, under the lead of Jack,

determined to leave, and for that purpose

crowded into a small boat which, from

overloading, was in danger of swamping.

"La Blanche then told his negroes that if they

were determined to go, they would be drowned,

and he would hire them a large boat to put them

across the river, and that they might have their

furniture if they would go and leave his

plantation and crop to ruin.

"They decided to go, and La Blanche did all a

man could to make that going safe.

"The account of General Phelps is the negro side

of the story; that above given is the story of

Mr. La Blanche's neighbors, some of whom

I know to be loyal men.

"An order against negroes being allowed in camp is the

reason they are outside.

"Mr. La Blanche is represented to be a humane

man, and did not consent to the 'exodus' of his

negroes.

"General Phelps, I believe, intends making this

a test case for the policy of the government.

I wish it might be so, for the difference, of

our action upon this subject is a source of

trouble. I respect his honest sincerity of

opinion, but I am a soldier, bound to carry out

the wishes of my government so long as I hold

its commission, and I understand that policy to

be the one I am pursuing. I do not feel at

liberty to pursue any other. If the policy

of the government is nearly that I sketched in

my report upon the subject and that which I have

ordered in this department, then the services of

General Phelps are worse than useless

here. If the views set forth in his report

are to obtain, then he is invaluable, for his

whole soul is in it, and he is a good soldier of

large experience, and no braver man lives.

I beg to leave the whole question with the

president, with perhaps the needless assurance

that his wishes shall be loyally followed, were

they not in accordance with my own, as I have

now no right to have any upon the subject.

"I write in haste, as the steamer 'Mississippi' is

awaiting this dispatch.

"Awaiting the earliest possible instructions, I have

the honor to be,

"B.

F. BUTLER, Major

General Commanding."

Gen. Phelps waited about six weeks for a

reply, but none came. Meanwhile the

negroes continued to gather at his camp.

He said, in regard to not receiving an answer,

"I was left to the inference that silence gives

consent, and proceeded therefore to take such

decided measures as appeared best calculated, to

me, to dispose of the difficulty."

Accordingly he made the following requisition

upon head-quarters:

"CAMP PARAPET,

LA., July 30, 1862.

"Captain

R. S. DAVIS, A. A. A. General, New

Orleans, La.:

"SIR: - I enclose herewith requisitions for

arms, accoutrements, clothing, camp and for the

defense of this point. The location is

swampy and unhealthy, and our men are dying at

the rate of two or three a day.

"The southern loyalists are willing, as I understand,

to furnish their share of the tax for the

support of the war; but they should also furnish

their quota of men, which they have not thus far

done. An opportunity now offers of

supplying the defficiency; and it is not safe to

neglect opportunities in war. I think

that, with the proper facilities, I could raise

the three regiments proposed in a short time.

Without holding out any inducements, or offering

any reward, I have now upward of three hundred

Africans organized into five companies, who are

all willing and ready to show their devotion to

our cause in any way that it may be put to the

test. They are willing to submit to

anything rather than to slavery.

"Society in the South seems to be on the point of

dissolution; and the best ay of preventing the

African from becoming instrumental in a general

state of anarchy, is to enlist them in the cause

of the Republic. If we reject his

services, any petty military chieftain, by

offering him freedom, can have them for the

purpose of robbery and plunder. It is for

the interests of the South, as well of the

North, that the African should be permitted to

offer his block for the temple of freedom.

Sentiments unworthy of the man of the present

day - worthy only of another Cain - could

alone prevent such an offer from being accepted.

"I would recommend that the cadet graduates of the

present year should be sent

[Pg. 192] -

to

South Carolina and this point to organize and

discipline our African levies, and that the more

promising non-commissioned officers and privates

of the army be appointed as company officers to

command them. Prompt and energetic efforts

in this direction would probably accomplish more

toward a speedy termination of the war, and an

early restoration of peace and unity, than any

other course which could be adopted.

I have the honor to remain, sir, very respectfully,

your obedient servant,

J. W. PHELPS,

Brigadier-General."

This reply was received:

NEW ORLEANS, July

31, 1862.

"GENERAL: - The general commanding wishes you to

employ the contrabands in and about your camp in

cutting down all the trees, &c., between your

lines and the lake, and in forming abatis,

according to the plan agreed upon between you

and Lieutenant Weitzel when he visited

you some time since. What wood is not

needed by you is much needed in this city.

For this purpose I have ordered the

quartermaster to furnish you with axes, and

tents for the contrabands to be quartered in.

"I

am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient

servant,

"By order of

Major-General BUTLER.

"R. S. DAVIS, Capt. and A. A. A. G.

"To Brigadier-General J. W. PHELPS,

Camp Parapet."

General Butler's effort to turn the attention of

Gen. Phelps to the law of Congress

recently passed was of no avail, that officer

was determined in his policy of warring on the

enemy; but finding General Butler as firm

in his policy of leniency, and knowing of his

strong pro-slavery sentiments prior to the war,

- notwithstanding his "contraband" order at

Fortress Monroe, - General Phelps felt as

though he would be humiliated if he departed

from his won policy, and became what he regarded

as a slave-driver, therefore he determined to

resign. He replied to General Butler

as follows:

"CAMP PARAPET, LA., July 31, 1862.

"Captain R. S. Davis, A. A. A. General,

New Orleans, La.:

'SIR: - The communication from your office of this

date, signed, 'By order of Major General

Butler,' directing me to employ the

'contrabands' in and about my camp in cutting

down all the trees between my lines and the

lake, etc., has just been received.

"In reply, I must state that while I am willing to

prepare African regiments for the defense of the

government against its assailants, I am not

willing to become the mere slave-driver which

you propose, having no qualifications in that

way. I am, therefore under the necessity

of tendering the resignation of my commission as

an officer of the army of the army of the United

States, and respectfully request a leave of

absence until it is accepted in accordance with

paragraph 29, page 12, of the general

regulations.

"While I am writing, at half-past eight o'clock P. M.,

a colored man is brought in by one of the

pickets who has just been wounded in the side by

a charge of shot, which he says was fired at him

by one of a party of three slave-hunters or

guerillas, a mile or more from our line of

sentinels. As it is some distance from the

camp to the lake, the party of wood-choppers

which you have directed will probably need a

considerable force to guard them against similar

attacks.

"I

have the honor to be, sir, very respectfully,

your obedient servant,

"J. W. PHELPS,

Brigadier-General."

Phelps was one of Butler's most

trusted commanders, and the latter endeavored,

but in vain, to have him reconsider his

resignation. General Butler wrote

him:

NEW ORLEANS,

August 2, 1862.

"GENERAL: - I was somewhat surprised to receive

your resignation for the reasons stated.

"When you were put in command at Camp Parapet, I sent

Lieutenant Weitzel, my chief engineer, to

make a reconnoissance of the lines of

Carrollton, and I understand it

[Pg. 193] -

was

agreed between you and the engineer that a

removal of the wood between Lake Pontchartrain

and the right of your intrenchment was a

necessary military precaution. The work

could not be done at that time because of the

stage of water and the want of men. But

now both water and men concur. You have

five hundred Africans organized into companies,

you write me. This work they are fitted to

do. It must either be done by them or my

soldiers, now drilled and disciplined. You

have said the location is unhealthy for the

soldier; it is not to the negro; it is not best

that these unemployed Africans should do this

labor? My attention is specially called to

this matter at the present time, because there

are reports of demonstrations to be made on your

lines by the rebels, and in my judgment it is a

matter of necessary precaution thus to clear the

right of your line, so that you can receive the

proper aid from the gun-boats on the lake,

besides preventing the enemy from having cover.

To do this the negroes ought to be employed; and

in so employing them I see no evidence of

'slave-driving' or employing you as a

'slave-driver.'

"The soldiers of the Army of the Potomac did this very

thing last summer in front of Arlington Heights;

are the negroes any better than they?

"Because of an order to do this necessary thing to

protect your front, threatened by the enemy, you

tender your resignation and ask immediate leave

of absence. I assure you I did not expect

this, either from your courage, your patriotism,

or your good sense. To resign in the face

of an enemy has not been the highest plaudit to

a soldier, especially when the reason assigned

is that he is ordered to do that which a recent

act of congress has specially authorized a

military commander to do, i. e., employ

the Africans to do the necessary work about a

camp or upon a fortification.

"General, your resignation will not be accepted by me,

leave of absence will not be granted, and you

will see to it that my orders, thus necessary

for the defense of the city, are faithfully and

diligently executed, upon the responsibility

that a soldier in the fields owes to his

superior. I will see that all proper

requisitions for the food, shelter, and clothing

of these negroes so at work are at once filled

by the proper departments. You will also

send out a proper guard to protect the laborers

against the guerilla force, if any, that may be

in the neighborhood.

"I am your obedient servant.

"BENJ. F. BUTLER,

Major-General Commanding.

"Brigadier-General J. W. PHELPS,

Commanding at Camp Parapet."

On the same day, General Butler wrote again to

General Phelps:

"NEW ORLEANS,

August 2, 1862.

"GENERAL" - By the

act of congress, as I understand it, the president of the United

States alone has the authority to employ Africans in arms as a part

of the military forces of the United States.

"Every law up to this time raising volunteer or militia

forces has been opposed to their employment.

The president has not as yet indicated his

purpose to employ the Africans in arms.

"The arms, clothing, and camp equipage which I have

here for the Louisiana volunteers, is, by the

letter of the secretary of war, expressly

limited to white soldiers, so that I have no

authority to divert them, however much I may

desire so to do.

"I do not think you are empowered to organize into

companies negroes, and drill them as a military

organization, as I am not surprised, but

unexpectedly informed you have done. I

cannot sanction this course of action as at

present advised, specially when we have need of

the services of the blacks, who are being

sheltered upon the outskirts of your camp, as

you will see by the orders for their employment

sent you by the assistant adjutant-general.

"I will send your application to the president but in

the mean time you must desist from the formation

of any negro military organization.

I am your

obedient servant,

"BENJ.

F. BUTLER,

Major-General Commanding.

"Brigadier-General PHELPS,

commanding forces at Camp

Parapet."

General Phelps' resignation was accepted by the

Government. He received notification of

the fact on the 8th of September and immediately

prepared to return to his farm in Vermont.

In parting with his officers, who were, like his

soldiers, much attached to him, he said:

"And now, with earnest wishes for your welfare,

and aspirations for the success of the great

cause for which you are here, I bid you good

bye." Says Parton:

[Pg. 194]

"When at length, the government had arrived at a negro policy, and

was arming slaves, the president offered General Phelps

a major-general's commission. He replied, it is said, that he

would willingly accept the commission if it were dated back to the

day of his resignation, so as to carry with it an approval of his

course at Camp Parapet. This was declined, and General

Phelps remains in retirement. I suppose the president

felt that an indorsement of General Phelps' conduct

would imply a censure of General Butler, whose conduct

every candid person, I think, must admit, was just, forbearing,

magnanimous."

General Butler

was carrying out the policy of the Government at that time, but it

was not long before he found it necessary to inaugurate a policy of

his own for the safety of his command. On the 5th of August

Breckenridge assaulted Baton Rouge, the capital of the State,

which firmly convinced General Butler of the necessity

of raising troops to defend New Orleans. He had somewhat

realized his situation in July and appealed to the "home

authorities" for reinforcements, but none could be sent.

Still, the Secretary of War said to him, in reply to his

application: "New Orleans must be held at all hazards."

With New Orleans threatened and no hope of

reinforcement, General Butler, on the 22d day of

August, before General Phelps had retired to private

life, was obliged to accept the policy of arming negroes. He

issued the following order :

"HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE GULF,

"NEW ORLEANS, August 22, 1862.

GENERAL ORDERS

NO. 63.

"Whereas on

the 23d day of April, in the year eighteen hundred and sixty-one, at

a public meeting of the free colored population of the city of New

Orleans, 'a military organization, known as the "Native Guards

"(colored,) had its existence, which military organization was duly

and legally enrolled as a part of the militia of the State, its

officers being commissioned by Thomas O. Moore, Governor and

Commander-in-Chief of the militia of the State of Louisiana, in the

form following, that is to say:

[L. S.]

[Signed,] THOS. O. MOORE.

" ' By the Governor:

[Signed.]

" 'P. D. Hardy, Secretary of State.

[Endorsed.]

" ' I,

Maurice Grivot, Adjutant and Inspector General of the State of

Louisiana, do hereby certify that _____ _____, named in the within

commission, did, on the second day of May, in the year 1861, deposit

in my office his written acceptance of the

[Pg. 195]

office to which he is commissioned, and his oath of

office taken according to law.

[Signed,] '"M. GRIVOT,

" 'Adjutant and Inspector General, La.'

" And whereas, said military

organization elicited praise and respect, and was complimented in

General Orders for its patriotism and loyalty, and was ordered to

continue during the war, in the words following:

" 'HEADQUARTERS LOUISIANA MlLITIA,

" ' Order No. 426.]

" 'Adjutant General's Office, March 24, 1862.

" 'I. - The Governor and Commander-in-Chief, relying

implicitly upon the loyalty of the free colored population of the

city and State for the protection of their homes, their property,

and for Southern rights, from the pollution of a ruthless invader,

and believing that the military organization which existed prior to

the 15th of February, 1862, and elicited praise and respect for the

patriotic motives which prompted it, should exist, for and during

the war, calls upon them to maintain their organization, and to hold

themselves prepared for such orders as may be transmitted to them.

" 'II. The colonel commanding will report without delay

to Major General Lewis, commanding State

militia.

" 'By order of THOS. O. MOORE, Governor.

[Signed,]

" 'M. GRIVOT, Adjutant General.'

"And whereas, said military organization, by the same

order, was directed to report to Major-General Lewis for

service, but did not leave the city of New Orleans when he did:

"Now, therefore, the Commanding General, believing that

a large portion of this militia force of the State of Louisiana are

willing to take service in the volunteer forces of the United

States, and be enrolled and organized to 'defend their homes from

ruthless invaders;' to protect their wives and children and kindred

from wrong and outrage; to shield their property from being seized

by bad men; and to defend the flag of their native country as their

fathers did under Jackson at Chalmette against Packenham

and his myrmidons, carrying the black flag of 'beauty and booty:'

"Appreciating their motives, relying upon their

'well-known loyalty and patriotism,' and with 'praise and respect

'for these brave men it is ordered that all the members of the

'Native Guards' aforesaid, and all other free colored citizens

recognized by the first and late governor and authorities of the

State of Louisiana as a portion of the militia of the State, who

shall enlist in the volunteer service of the United States, shall be

duly organized by the appointment of proper officers, and accepted,

paid, equipped, armed and rationed as are other volunteer troops of

the United States, subject to the approval of the President of the

United States. All such persons are required at once to report

themselves at the Touro Charity Building, Front Levee St., New

Orleans, where proper officers will muster them into the service of

the United States.

By command of Major General Butler:

K. S. DAVIS, Capt. and A. A. A. G."

Notwithstanding the harsh

treatment they had been receiving from Military-Governor Shepley

and the Provost Guard, the rendezvous designated was the scene of a

busy throng the next day. Thousands of men were enlisted

during the first week, and in fourteen days a regiment was

organized. The first regiment's line officers were colored,

and the field officers were white. Those who made up this regiment

were not all free negroes by more than half. Any negro who

would swear that he was free, if physically good, was accepted, and

of the many thousand slave fugitives in the city from distant

plantations, hundreds found their way into Touro building and

ultimately into the ranks of the three regiments formed at that

building. The second, like the first, had all colored line

officers; the third was officered regardless of color. This

was going beyond the line laid down by General Phelps.

He proposed that white men should take com-

[Pg. 196]

mand of these

troops exclusively. By November these

three regiments were in the field, where in

course of time they often met their former

masters face to face and exchanged shots with

them. The pro-slavery men of the North and

their newspapers endeavored to make the soldiers

in the field believe that the negroes would not

fight; while not only the papers and the

soldiers, but many officers, especially those

from the West Point Academy, denounced

General Butler for organizing the regiments.

General Weitzel, to whose command these

regiments were assigned in an expedition up the

river, object to them, and asked Butler

to relieve him of the command of the expedition.

Butler wrote him in reply:

[Pg. 197] - BLANK

[Pg. 198]

POINT ISABEL, TEXAS

Phalanx soldiers on duty, throwing up

earthworks.

[Pg. 199]

General Butler continued General Weitzel

in command but placed the negroes under another

officer. However, General Weitzel,

like thousands of others, changed his mind in

regard to the colored troops. "If he was

not convinced by General Butler's

reasoning" says Parton, "he must have

been convinced by what he saw of the conduct of

those very colored regiments at Port Hudson,

where he himself gave such a glorious example of

prudence and gallantry."

Notwithstanding these troops did good service, it did

not soften or remove very much of the prejudice

at the North against the negro soldiers, nor in

the ranks of the army. Many incidents

might be cited to show the feeling of bitterness

against them.* However, General Butler's

example was followed very soon by every officer

in command, and by the time the President's

Emancipation Proclamation was issued there were

not less than 10,000 negroes armed and equipped

along the Mississippi river. Of course the

Government knew nothing of this.(?) Not

-------------------------

* In

November, while the 2nd Regiment was guarding

the Opelousas railway, about twenty miles from

the Algiers, La., their pickets were fired upon,

and quite a skirmish and firing was kept up

during the night. Next morning the cane

field along the railroad was searched but no

trace of the firing party was found. A

company of the 8th Vermont (white) Regiment was

encamped below that of the 2nd Regiment, but

they broke camp that night and left. The

supposition was that it was this company who

fired upon and drove in the pickets of the

Phalanx regiment. [Pg. 200]

only armed, but some of them

had been in skirmishes with the enemy.

That as the Phalanx they were invaluable in

crushing the rebellion, let their acts of

heroism tell. In the light of history and

of their own deeds, it can be said that in

courage, patriotism and dash, they were second

to no troops, either in ancient or modern

armies. They were enlisted after rigid

scrutiny, and the examination of every man by

competent surgeons. Their acquaintance

with the country in which they marched, encamped

and fought, made them in many instances superior

to the white troops. Then to strengthen

their valor and tenacity, each soldier of the

Phalanx knew when he heard the long roll beat to

arms, and the bugle sound the charge, that they

were not to go forth to meet those who regarded

them as opponents in arms, but who met them as a

man in his last desperate effort for life woud

meet demons; they knew, also, that there was no

reserve - no reinforcements behind to support

them when they went to battle; their alternative

was life or death. It was the

consciousness of this fact that made the black

phalanx a wall of adamant to the enemy.

The not unnatural willingness of the white soldiers to

allow the negro troops to stop the bullets that

they would otherwise have to receive was shown

in General Bank's Red River Campaign.

At Pleasant Grove, Dickey's black brigade

prevented a slaughter of the Union troops.

The black Phalanx were represented there by a

brigade attached to the first division of the

19th Corps. When the confederates routed

the army under Banks at Sabine Cross

Roads, below Mansfield, they drove it for

several hours toward Pleasant Grove despite the

ardor of the combined forces of Banks and

Franklin. It became apparent that unless

the confederates could be checked at this point,

all was lost. General Emory

prepared for the emergency on the western edge

of a wood, with an open field sloping toward

Mansfield. Here General Dwight

formed a brigade of the black Phalanx across the

road. Hardly was the line formed when out

came the gallant foe driving 10,000 men before

them. Flushed with two days' victory, they

came

[Pg. 201]

THE RECRUITING OFFICE

Negroes enlisting in the army, and being

examined by surgeons.

[Pg. 202] - BLANK

[Pg. 203]

charging at double quick time,

but the Phalanx held its fire until the enemy

was close upon them, and then poured a deadly

volley into the ranks of the exultant foe,

stopping them short and mowing them down like

grass. The confederates recoiled, and now

began a fight such as was always fought when the

Southerners became aware that black soldiers

were in front of them, and for an hour and a

half they fought at close quarters, ceasing only

at night. Every charge of the enemy was

repulsed by the steady gallantry of General

Emory's brigade and the black Phalanx,

bering three to one. During this memorable

campaign the Phalanx more than once met the

enemy and accepted the face of their black flag

declarations. The confederates knew full

well that every man of the Phalanx would fight

to the last; they had learned that long before.

As early as June, 1863, General Grant was

compelled in order to show a bold front to

Gens. Pemberton and Johnston at the

same time, while besieging Vicksburg, to draw

nearly all the troops from (Milliken's Bend) to

his support, leaving three infantry regiments of

the black Phalanx and a small force of white

cavalry to hold this, to him an all important

post. Millikens Bend was well fortified,

and with a proper garrison was in condition to

stand a siege. Brigadier-General Dennis

was in command, and the troops consisted of the

9th and 11th Louisiana Regiments, the 1st

Mississippi and a small detachment of white

cavalry, in all about 1,400 men, raw recruits.

General Dennis was in command, and the

troops consisted of the 9th and 11th Louisiana

Regiments, the 1st Mississippi and a small

detachment of white cavalry, in all about 1,400

men, raw recruits. General Dennis

looking upon the place more as a station for

organizing and drilling the Phalanx, had made no

particular arrangements in anticipation of an

attack. He was surprised, therefore, when

a force of 3,000 men, under General Henry

McCulloch, from the interior of Louisiana,

attacked and drove his pickets and two companies

of the 23d Iowa Cavalry, (white) up to the

breast works of the Bend. The movement was

successful, however, and the confederates,

holding the ground, rested for the night, with

the expectation of marching into the

fortifications in the morning, to begin a

massacre, whether a resistance should

[Pg. 204]

be shown them or not. The

knowledge this little garrison had of what the

morrow would bring it, doubtless kept the

soldiers awake, preparing to meet the enemy and

their own fate. About 3 o'clock, in the

early grey of the morning, the confederate line

was formed just outside of the intrenchments;

suddenly with fixed bayonets the men came

rushing over the works, driving everything

before them and shouting, "No quarter! No

quarter to negroes or their officers!" In

a moment the blacks formed and met them, and now

the battle began in earnest, hand to hand.

The gunboats "Choctaw" and "Lexington" also came

up as the confederates were receiving the

bayonets and the bullets of the Unionists, and

lent material assistance. The attacking

force had flanked the works and was pouring in a

deadly, enfilading musketry fire. The

defenders fell back out of the way of the

gunboat's shells, but finally went forward again

with what was left of their 150 white allies,

and drove the enemy before them and out of the

captured works. One division of the

enemy's troops hesitated to leave a redoubt,

when a company of brave black men dashed forward

at double-quick time and engaged them. The

enemy stood his ground, and soon the rattling

bayonets rang out amid the thunders of the

gunboats and the shouts of enraged men; but they

were finally driven out, and their ranks thinned

by the "Chocktaw" as they went over the works.

The news reached General Grant and he

immediately dispatched General Mower's

brigade with orders to re-enforce Dennis

and drive the confederates beyond the Tensas

river.

A battle can be best described by one who observed it.

Captain Miller who not only was an

eye-witness, but participated in the Milliken's

Bend fight, writes as follows:

"We were attacked here on June 7,

about three o'clock in the morning, by a brigade

of Texas troops, about two thousand five hundred

in number. We had about six hundred men to

withstand them, five hundred of them negroes.

I commanded Company I, Ninth Louisiana. We

went into the fight with thirty-three men.

I had sixteen killed, eleven badly wounded, and

four slightly. I was wounded slightly on

the head, near the forefinger; that will account

for this miserable style of penmanship.

"Our regiments had about three hundred men in the

fight. We had one colonel wounded, four

captains wounded, two first and two second

lieutenants killed, five lieutenants wounded,

and three white orderlies killed, and one

wounded in the hand, and two fingers taken off.

The list of killed and wounded officers

comprised nearly all the officers present with

the regiment, a majority of the rest being

absent recruiting.

"We had about fifty men killed in the regiment and

eighty wounded; so you can judge of what part of

the fight my company sustained. I never

felt more grieved and [Pg. 205]

BATTLE of MILLIKEN'S BEND

[Pg. 206] - BLANK

[Pg. 207]

sick at heart,

than when I saw how my brave soldiers had been

slaughtered, - one with six wounds, all the rest

with two or three, none less than two wounds.

Two of my colored sergeants were killed: both

brave, noble men, always prompt, vigilant, and

ready for the fray. I never more wish to

hear the expression, 'The niggers wont fight.'

Come with me, a hundred yards from where I sit,

and I can show you the wounds that cover the

bodies of sixteen as brave, loyal, and patriotic

soldiers as ever drew bead on a rebel.

"The enemy charged us so close that we fought with our

bayonets, hand to hand, I have six broken

bayonets to show how bravely my men fought.

The Twenty-third Iowa joined my company on the

right; and I declare truthfully that they had

all fled before our regiment fell back, as we

were all compelled to do.

"Under command of Col. Page, I led the Ninth and

Eleventh Louisiana when the rifle-pits were

retaken and held by our troops, our two

regiments doing the work.

"I narrowly escaped death once. A rebel took

deliberate aim at me with both barrels of his

gun; and the bullets passed so close to me that

the powder that remained on them burnt my cheek.

Three of my men, who saw him aim and fire,

thought that he wounded me each fire; One of

them was killed by my side, and he felt on me,

covering my clothes with his blood; and, before

the rebel could fire again, I blew his brains

out with my gun.

"It was a horrible fight, the worst I was ever engaged

in, - not even excepting Shiloh. The enemy

cried, 'No quarter!' but some of them were very

glad to take it when made prisoners.

"Col. Allen of the Sixteenth Texas, was killed

in front of our regiment, and Brig. Gen.

Walker was wounded. We killed about

one hundred and eighty of the enemy. The

gunboat "Choctaw" did good service shelling

them. I stood on the breastworks after we

took them, and gave the elevations and direction

for the gunboat by pointing my sword; and they

sent a shell right into their midst, which sent

them in all directions. Three shells fell

there and sixty-two rebels lay there when the

fight was over.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

"This battle satisfied the slave-masters of the South

that their charm was gone; and that the negro as

a slave, was lost forever. Yet there was

one fact connected with the battle of Milliken's

Bend which will descend to posterity, as

testimony against the humanity of slave-holders;

and that is, that no negro was ever found alive

that was taken a prisoner by the rebels in this

fight.

The

Department of the Gulf contained a farm greater

proportion of the Phalanx than did any other

Department, and there were very few, if any,

important engagement, and there were very few,

if any, important engagements fought in this

Department in which the Phalanx did not take

part.

It is unpleasant here, in view of the valuable services

rendered by the Phalanx, to be obliged to record

that the black soldiers were subjected to many

indignities, and suffered much at the hands of

their white fellow comrades in arms.

Repeated assaults and outrages were committed

upon black men wearing the United States'

uniform, not only by volunteers but conscripts

from the various States, and frequently by

confederate prisoners who had been paroled by

the United States; these outrages were allowed

to take place, without interference by the

commanding officers, who apparently did not

observe what was going on.

At Ship Island, Miss., there wee three companies of the

13th Maine, General Neal Dow's old

regiment, and seven companies of the 2nd

Regiment Phalanx, commanded by Colonel

Daniels, which constituted the garrison at

that point. Ship Island was the key to New

Orleans. On

[Pg. 208]

the opposite shore was a

railroad leading to Mobile by which

re-enforcements were going forward to

Charleston. Colonel Daniels

conceived the idea of destroying the road to

prevent the transportation of the confederate

troops. Accordingly, with about two

hundred men he landed at Pascagoula, on the

morning of the 9th of April. Pickets were

immediately posted on the outskirts of the town,

while the main body marched up to the hotel.

Before long some confederate cavalry, having

been apprised of the movement, advanced, drove

in the pickets, and commenced an attack on the

force occupying the town. The cavalry made

a bold dash upon the left of the negroes, which

was the work of but a moment; the brave blacks

met their charge manfully, and emptied the

saddles of the front rank, which caused the rear

ones first to halt and then retire. The

blacks were outnumbered, however, five to one,

and finally were forced to abandon the town;

they went, taking with them the stars and

stripes which they had hoisted upon the hotel

when entering it. They fell back towards

the river to give the gunboat "Jackson" a chance

to shell their pursuers, but the movement

resulted in an apparently revengeful act on the

part of the crew of that vessel, they having

previously had some of their number killed in

the course of a difficulty with a black sentry

at Ship Island.

The commanding officer of the land force, doubtless

from prudential reasons, omitted to state in

this report that the men fought their way

through the town while being fired upon from

house-tops and windows by boys and women.

That the gunboat opened fire directly on them

when they were engaged in a hand to hand

conflict, which so completely cut off a number

of the men from the main body of the troops that

their capture appeared certain. Major

Dumas, however, seeing the condition of

things, put spurs to his horse and went to their

succor, reaching them just as a company of the

enemy's cavalry made a charge. The major,

placing himself at the head of the hard-pressed

men, not only repulsed the cavalry and rescued

the squad, but captured the enemy's stand-

[Pg. 209] - BLANK

[Pg. 210]

UNLOADING GOVT. STORES

[Pg. 211]

ard-bearer. The retreating

force reached their transport with the loss of

only one man; they brought with them some

prisoners and captured flags. Colonel

Daniels, in his report, speaks as follows of

the heroism of the soldiers:

* *

*

*

*

*

*

"The expedition was a perfect

success, accomplishing all that was intended;

resulting in the repulse of the enemy in every

engagement with great loss; whilst our casualty

was only two killed and eight wounded.

Great credit is due to the troops engaged, for

their unflinching bravery and steadiness under

this their first fire, exchanging volley after

volley with the coolness of veterans; and for

their determined tenacity in maintaining their

position, and taking advantage of every success

that their courage and valor gave them; and also

to their officers, who were cool and determined

throughout the action, fighting their commands

against five times their numbers, and confident

throughout of success, - all demonstrating to

its fullest extent that the oppression which

they have heretofore undergone from the hands of

their foes, and the obloquy that had been

showered upon them by those who should have been

friends, had not extinguished their manhood, or

suppressed their bravery, and that they had

still a hand to wield the sword, and a heart to

vitalize its blow.

"I would particularly call the attention of the

Department to Major F. E. Dumas, Capt.

Villeverd, and Lieuts. Jones and Martin,

who were constantly in the thickest of the

fight, and by their unflinching bravery, and

admirable handling of their commands,

contributed to the success of the attack, and

reflected great honor upon the flag under and

for which they so nobly struggled.

Repeated instances of individual bravery among

the troops might be mentioned; but it would be

invidious where all fought so manfully and so

well.

"I have the honor to be, most respectfully your

obedient servant,

"N. U. DANIELS,

"Col. Second Regiment La. N. G. Vols.,

Commanding Post.

The 2nd Regiment, with the exception of the

Colonel, Lieut. Colonel and Adjutant, was

officered by negroes, many of whom had worn the

galling chains of slavery, while others were men

of affluence and culture from New Orleans and

vicinity.

The 2nd Regiment

had its full share of prejudice to contend with,

and perhaps suffered more from that cause than

any other regiment of the Phalanx. Once

while loading transports at Algiers, preparatory

to embarking for Ship Island, they came in

contact with a section of the famous Nim's

battery, rated as one of the finest in the

service. The arms of the 2nd Regiment were

stacked and the men were busy in loading the

vessel, save a few who were doing guard duty

over the ammunition stored in a shed on the

wharf. One of the battery-men attempted to

enter the shed with a lighted pipe in his mouth,

but was prevented by the guard. It was

more than the Celt could stand to be ordered by

a negro; watching for a chance when the guard

about-faced, he with several others sprang upon

him. The guard gave the Phalanx signal,

and instantly hundreds of black men secured

their arms and rushed to the relief of their

comrade. The battery-men

[Pg. 212]

jumped to their guns, formed

into line and drew their sabres. Lieut.

Colonel Hall, who was in command of the 2nd

Regiment, stepped forward and demanded to know

of the commander of the battery if his men

wanted to take the men the guard had arrested.

"Yes," was the officer's reply, "I want you to

give them up." "Not until they are dealt

with, " said Colonel Hall. And then

a shout and yell, such as the Phalanx only were

able to give, rent the air, and the abortive

menace was over. The gunners returned

their sabres and resumed their work.

Col. Hall, who always had perfect control of

his men, ordered the guns stacked, put on a

double guard, and the men of the 2nd Regiment

resumed their labor of loading the transport.

Of course this was early in the struggle, and

before a general enlisted of the blacks.

The first, second and third regiments of the Phalanx

were the nucleus of the one hundred and eighty

that eventually did so much for the suppression

of the rebellion and the abolition of slavery.

The 1st and 3rd Regiments went up the

Mississippi; the 2nd garrisoned Ship Island and

Fort Pike, on Lake Ponchartrain, after

protecting for several months the Opelousa

railroad, so much coveted by the confederates.

A few weeks after the fight of the 2nd Regiment at

Pascagoula, General Banks laid siege to

Port Hudson, and gathered there all the

available forces in his department. Among

these wee the 1st and 3rd Infantry Regiments of

the Phalanx. On the 23rd of May the

federal forces, having completely invested the

enemy's works and made due preparation, were

ordered to make a general assault along the

whole line. The attack was intended to be

simultaneous but in this it failed. The

Union batteries opened early in the morning, and

after a vigorous bombardment Generals Weitzel,

Grover and Paine, on the right,

assaulted with vigor at 10 A. M., while Gen.

Augur in the center, and General W. T.

Sherman on the left, did not attack till 2

P. M.

Never was fighting more heroic than that of the federal

army and especially that of the Phalanx

regiments

[Pg. 213]

If valor could have triumphed

over such odds, the assaulting forces would have

carried the works, but only abject cowardice or

pitiable imbecility could have lost such a

position under existing circumstances. The

negro regiments on the north side of the works

vied with the bravest, making three desperate

charges on the confederate batteries, losing

heavily, but maintaining their position in the

advance all the while.

The column in moving to the attack went through the

woods in their immediate front, and then upon a

plane, on the farther side of which, half a mile

distant, were the enemy's batteries. The

field was covered with recently felled trees,

through the interlaced branches of which the

column moved, and for two or more hours

struggled through the obstacles, stepping over

their comrades who fell among the entangled

brushwood pierced by bullets or torn by flying

missiles, and braved the hurricane of shot and

shell.

What did it avail to hurl and few thousand troops

against those impregnable works? The men

were not iron, and were they, it would have been

impossible for them to have kept erect, where

trees three feet in diameter were crashed down

upon them by the enemy's shot; they would have

been but as so many ten-pins set up before

skillful players to be knocked down.

The troops entered an enfilading fire from a masked

battery which opened upon them as they neared

the fort, causing the column first to halt, then

to waver and stagger; but it recovered and again

pressed forward, closing up the ranks as fast as

the enemy's shells thinned them. On the

left the confederates had planted a six-gun

battery upon an eminence, which enable them to

sweep the field over which the advancing column

moved. In front was the large fort, while

the right of the line was raked by a redoubt of

six pieces of artillery. On after another

of the works had been charged, but in vain.

The Michigan, New York and Massachusetts troops

- braver than whom none ever fought a battle -

had been hurled back from the place, leaving the

field strewn with their dead and woun-

[Pg. 214]

ded. The works must be

taken. General Nelson was ordered

by General Dwight to take the battery on

the left. The 1st and 3rd Regiments went

forward at double quick time, and they were soon

within the line of the enemy's fire.

Louder than the thunder of Heaven was the

artillery rending the air shaking the earth

itself; cannons, mortars and musketry alike

opened a fiery storm upon the advancing

regiments; an iron shower of grape and round

shot, shells and rockets, with a perfect tempest

of rifle bullets fell upon them. On they

went and down, scores falling on right and left.

"The flag, the flag!" shouted the black

soldiers, as the standard-bearer's body was

scattered by a shell. Two file-closers

struggled for its possession; a ball decided the

struggle. They fell faster and faster;

shrieks, prayers and curses came up from the

fallen and ascended to Heaven. The ranks

closed up while the column turned obliquely

toward the point of fire, seeming to forget they

were but men. Then the cross-fire of grape

shot swept through their ranks, causing the

glittering bayonets to go down rapidly.

"Steady men, steady," cried bold Cailloux, his

sword uplifted, his face the color of the

sulphureous smoke that enveloped him and his

followers, as they felt the deadly hail which

cam apparently from all sides. Captain

Caillous* was killed with the col-

-------------------------

*Captain Andre Callioux fell,

gallently leading his men (Co. #) in the attack.

With many others of the charging column, his

body lay between the lines of the Confederates

and Federals, but nearer the works of the

former, whose sharp-shooters guarded it night

and day, and thus prevented his late comrades

from removing it. Several attempts were

made to obtain the body, but each attempt was

met with a terrific storm of lead. It was

not until after the surrender that his remains

were recovered, and then taken to his native

city, New Orleans. The writer of this

volume, himself wounded, was in the city at the

time,and witnessed the funeral pageant of the

dead here, the like of which was never before

seen in that, nor, perhaps, in any other

American city, in honor of a dead negro.

The negro captains of the 2nd Regiment acted as

pall-bearers, while a long procession of civic

societies followed in the rear of detachments of

the Phalanx. A correspondent who witnessed

the scene thus describes it:

"* * *

* *

The arrival of the body developed to the white

population here that the colored people had

powerful organizations in the form of civic

societies; as the Friends of the Order, of which

Capt. Callioux was a prominent member,

received the body, and had the coffin containing

it, draped with the American flag, exposed in

state in the commodious hall. Around the

coffin, flowers were strewn in the greatest

profusion, and candles were kept continually

burning. All the rites of the Catholic

Church were strictly complied with. The

guard paced silently to and fro, and altogether

it presented as solemn a scene as was ever

witnessed.

"In due time, the band of the Forty-second

Massachusetts Regiment made its appearance, and

discoursed the customary solemn airs. The

officiating priest, Father Le Maistre, of

the Church of St. Rose of Lima, who has paid not

the least attention to the excommunication and

denunciations issued against him by the

archbishop of this

[Pg. 215]

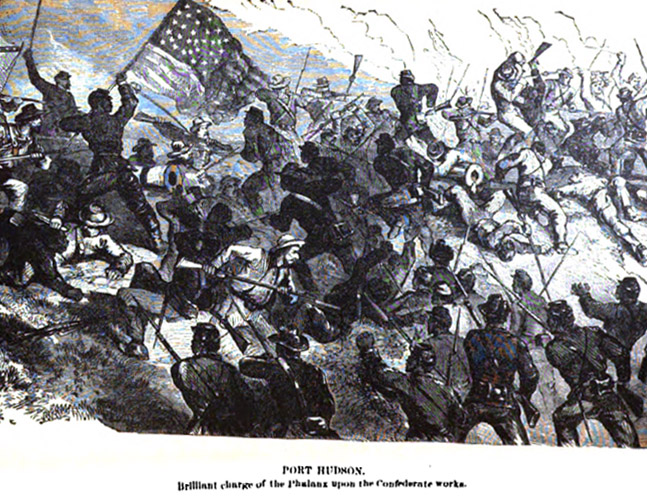

PORT HUDSON.

Brilliant charge of the Phalanx upon the

Confederate works.

[Pg. 216] - BLANK

[Pg. 217]

ors in his hands; the column seemed to melt

away like snow in sunshine, before the

enemy's murderous fire; the pride, the

flower of the Phalanx, had fallen.

Then, with a daring that veterans only can

exhibit, the blacks rushed forward and up to

the brink and base of the fortified

elevation, with a shout that rose above it.

The defenders emptied their rifles, cannon

and mortars upon the very heads of the brave

assaulters, making of them a human hecatomb.

Those who escaped found their way back to

shelter as best they could.

The battery was not captured; the battle was lost to

all except the black soldiers; they, with

their terrible loss,

---------------

this diocese, then performed

the Catholic service for the dead.

After the regular services, he ascended to

the president's chair, and delivered a

glowing and eloquent eulogy on the virtues

of the deceased. He called upon all

present to offer themselves, as Callioux

had done, martyrs to the cause of justice,

freedom, and good government. It was a

death the proudest might envy.

"Immense crowds of colored people had by this time

gathered around the building and the streets

leading thereto were rendered almost

impassable. Two companies of there to

act as an escort; and Esplanade Street, for

more than a mile, was lined with colored

societies, both male and female, in open

order, waiting for the hearse to pass

through.

"After a short pause, a sudden silence fell upon the

crowd, the band commenced playing a dirge;

and the body was brought from the hall on

the shoulders of eight soldiers, escorted by

six members of the society, and six colored

captains, who acted as pall-bearers.

The corpse was conveyed to the hearse

through a crowd composed of both white and

black people, and in silence profound as

death itself. Not a sound was heard

save the mournful music of the band, and not

a head in all that vast multitude but was

uncovered.

"The procession then moved off in the following order:

The hearse containing the body, with

Capts. J. W. Ringgold, W. B. Barrett, S. J.

Wilkinson, Eugene Mailleur, J. A. Glea,

and A. St. Leger, (all of whom, we

believe, belong to the Second Louisiana

Native Guards), and six members of The

Friends of the Order, as pall-bearers; about

a hundred convalescent sick and wounded

colored soldiers; the two companies of the

Sixth Regiment; a large number of colored

officers of all native guard regiments; the

carriages containing Capt. Callioux's

family, and a number of army officers;

followed by a large number of private

individuals, and thirty-seven civic and

religious societies.

"After moving through the principal down-town streets,

the body was taken to the Beinville-street

cemetery and there interred with military

honors due his rank." * *

The

following lines were penned at the time:

ANDRE CAILLOUX.

He lay

just where he fell,

Soddening in a fervid summer's sun.

Guarded by an enemy's hissing shell,

Rotting beneath the sound of rebels'

gun

Forty consecutive days,

In sight of his own tent,

And the remnant of his regiment.

He lay just where he fell,

Nearest the rebel's redoubt and

trench,

Under the very fire or hell,

A volunteer in a country's defence,

Forty consecutive days.

And not a murmur of discontent,

Went from the loyal black regiment |

A flag

of truce couldn't save,

No, nor humanity could not give

This sable warrior a hallowed grave,

Nor army of the Gulf retrieve.

Forth consecutive days,