|

The

appearance of the negro in the Union army

altered the state of affairs very much.

The policy of the general Government was

changed, and the one question which Mr.

Lincoln had tried to avoid became the

question of the war. General

Butler, first at Fortress Monroe and

then at New Orleans, had defined the status

of the slave, "contraband " and then

"soldiers," in advance of the Emancipation

Proclamation. General Hunter,

in command at the South, as stated in a

previous chapter, had taken an early

opportunity to strike the rebellion in its

most vital part, by arming negroes in his

Department, after declaring them free.

Notwithstanding the President revoked Hunter's

order, a considerable force was organized

and equipped as early as December, 1862; in

fact a. regiment of blacks was under arms

when the President issued the Emancipation

Proclamation. This regiment, the 1st

South Carolina, was in command of Colonel

T. W. Higginson, who with a portion of

his command ascended the St. Mary's river on

transports, visited Florida and Georgia, and

had several engagements with the enemy.

After an absence of ten or more days, the

expedition returned to South Carolina

without the loss of a man.

Had there been but one army in the field, and the

fighting confined to one locality, the

Phalanx would have been mobilized, but as

there were several armies it was distributed

among the several forces, and its conduct in

[Pg. 250]

battle, camp, march and bivouac, was spoken

of by the commanders of the various armies

in terms which any class of soldiers, of any

race, might well be proud of.

General Grant, on the 24th of July,

following the capture of Vicksburg, wrote to

the Adjutant-General:

"The negro troops are easier to preserve

discipline among than are our white troops,

and I doubt not will prove equally good for

garrison duty. All that have been

tried have fought bravely."

This was six days after the unsurpassed bravery of the

54th Regiment Massachusetts

Volunteers—representing the North in the

black Phalanx—had planted its blood stained

banner on the ramparts of Fort Wagner.

It was

the Southern negroes, who, up to this time,

had reddened the waters of the Mississippi.

It was the freedman's blood

that had moistened the soil, and if

ignorance could be so intrepid still greater

daring might be expected on the part

of the more intelligent men of the race.

The assault on Fort "Wagner, July 18, 1803, was one of

the most heroic of the whole four years'

war. A very

graphic account of the entire movement is

given in the following article:

"At daylight, on the morning of the 12th

of July a strong column of our troops

advanced swiftly to the attack of Fort

Wagner. The rebels were well prepared,

and swept with their guns every foot of the

approach; to the fort, but our soldiers

pressed on, and gained a foothold on the

parapet; but, not being supported by other

troops, nor aided by the guns of the fleet,

which quietly looked on, they were forced to

retreat, leaving many of their comrades in

the hands of the enemy.

"It is the opinion of many that if the fleet had moved

up at the same time, and raked the fort with

their guns, our troops would have succeeded

in taking it; but the naval captains said in

their defence that they knew nothing of the

movement, and would have gladly assisted in

the attack had they been notified.

"This, unfortunately, was not the only instance of a

want of harmony or co-operation between the

land and naval forces operating against

Charleston. Had they been under the

control of one mind, the sacrifice of life

in the siege of Forts Wagner and Sumter

would have been far less. We will not

assume to say which side was at fault, but

by far the greater majority lay the blame

upon the naval officers. Warfare

kindles up the latent germs of jealousy in

the human breast, and the late rebellion

furnished many cruel examples of its

effects, both among the rebels and among the

patriots. We have had the misfortune

to witness

[Pg. 251]

them in more than one

campaign, and upon more than one bloody and

disastrous field.

"By the failure of this attack, it was evident that the

guns of Wagner must lie silenced before a

successful assault with infantry could be

made; and, in order to accomplish this, a

siege of greater or less duration was

required. Therefore earthworks were

immediately thrown up at the distance of

about a thousand yards from the fort, and

the guns and mortars from Folly Island

brought over to be placed in position.

"This Morris Island is nothing but a narrow bed of

sand, about three miles in length, with a

breadth variable from a few hundred yards to

a few feet. Along the central portion

of the lower end a ridge of white sand hills

appear, washed on one side by the tidal

waves, and sloping on the other into broad

marshes, more than two miles in width, and

intersected by numerous deep creeks.

Upon the extreme northern end, Battery

Gregg, which the rebels used in reducing

Fort Sumter in 1861, had been strengthened,

and mounted with five heavy guns, which

threw their shot more than half way down the

island. A few hundred yards farther

down the island, and at its narrowest

portion, a strong fort had been erected, and

armed with seventeen guns and mortars.

This was the famous Fort Wagner; and, as its

cannon prevented any farther progress up the

island, it was necessary to reduce it before

our forces could approach nearer to Fort

Sumter.

" It was thought by our engineers that a continuous

bombardment of a few days by our siege

batteries and the fleet might dismount the

rebel cannon, and demoralize the garrison,

so that our brave boys, by a sudden rush,

might gain possession of the works.

Accordingly our seige train was brought over

from Folly Island, and a parallel commenced

about a thousand yards from Wagner.

Our men worked with such energy that nearly

thirty cannon and mortars were in position

on the 17th of July. On the 18th of

July the bombardment commenced. The

land batteries poured a tempest of shot into

the south side of Wagner, while the fleet

moved up to within short range, and battered

the east side with their great guns. In the

mean time the rebels were not silent, but

gallantly stood to their guns, returning

shot for shot with great precision.

But, after a few hours, their fire

slackened; gun after gun be came silent, as

the men were disabled, and, when the clock

struck four in the afternoon, Wagner no

longer responded to the furious cannonade

the Federal forces. Even the men had taken

shelter beneath the bomb-proofs, and no sign

of life was visible about the grim and

battered fortress.

"Many of our officers were now so elated with the

apparent result of demolition, that they

urged General Gillmore to

allow? them to assault the fort as soon as

it became dark. General

Gillmore yielded to the solicitations of

the officers, but very reluctantly, for he

was not convinced that the proper time had

arrived; but the order was finally given for

the

attack to take place just after dark.

Fatal error as to time, for our troops in

the daytime would have been successful,

since they would not

[Pg. 252]

have collided with each other; they could

have seen their foes, and the arena of

combat, and the fleet could have assisted

them with their guns, and prevented the

landing of the re-enforcements from

Charleston.

" It was a beautiful and calm evening when the troops

who were to form the assaulting column moved

out on to the broad and smooth beach left by

the receding tide.

"The last rays of the setting sun illumined the grim

walls and shattered mounds of Wagner with a

flood of crimson light, too soon, alas!

to be deeper dyed with the red blood of

struggling men.

"Our men halted, and formed their ranks upon the beach,

a mile and more away from the deadly breach.

Quietly they stood leaning upon their guns,

and awaiting the signal of attack.

There stood, side by side, the hunter of the

far West, the farmer of the North, the stout

lumber man from the forests of Maine, and

the black Phalanx Massachusetts had armed

and sent to the field.

"In this hour of peril there was no jealousy, no

contention. The black Phalanx were to

lead the forlorn hope. And they were

proud of their position, and conscious of

its danger. Although we had seen many

of the famous regiments of the English,

French, and Austrian armies, we were never

more impressed with the fury and majesty of

war than when we looked upon the solid mass

of the thousand black men, as they stood,

like giant statues of marble, upon the

snow-white sands of the beach, waiting the

order to advance. And little did we

think, as we gazed with admiration upon that

splendid column of four thousand brave men,

that ere an hour had passed, half of them

would be swept away, maimed or crushed in

the gathering whirlwind of death! Time

passed quickly, and twilight was fast

deepening into the darkness of night, when

the signal was given. Onward moved the

chosen and ill-fated band, making the earth

tremble under the heavy and monotonous tread

of the dense mass of thousands of men.

Wagner lay black and grim in the distance,

and silent. Not a glimmer of light was

seen. Not a gun replied to the bombs

which our mortars still constantly hurled

into the fort. Not a shot was returned

to the terrific volleys of the giant frigate

Ironsides, whose shells, ever and anon,

plunged into the earth works, illuminating

their recesses for an instant in the glare

of their explosion, but revealing no signs

of life.

"Were the rebels all dead? Had they fled from the

pitiless storm which our batteries had

poured down upon them for so many hours?

Where were they?

"Down deep beneath the sand heaps were excavated great

caverns, whose floors were level with the

tide, and whose roofs were formed of huge

trunks of trees laid in double rows.

Still above these massive beams sand was

heaped so deeply that even our enormous

shells could not penetrate the roofs, though

they fell from the skies above. In

these dark subterranean retreats two

thousand men lay hid, like panthers in a

swamp, waiting to leap forth in fury upon

their prey.

"The signal given, our forces advanced rapidly towards

the fort,

[Pg. 253] - BLANK

[Pg. 254]

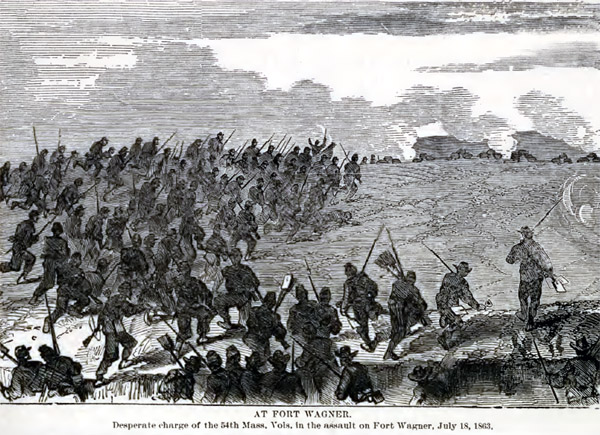

AT FORT WAGNER

Desperate charge of the 54th Mass., Vols.,

in the assault on Fort Wagner, July 1__,

1864

[Pg. 255]

while our mortars in the rear tossed their

bombs over their heads. The

Fifty-fourth Massachusetts [Phalanx

Regiment] led the attack, supported by the

6th Conn., 48th N. Y., 3rd N. H., 76th Penn.

and the 9th Maine Regiments. Onward

swept the immense mass of men, swiftly and

silently, in the dark shadows of night.

Not a flash of light was seen in the

distance! No sentinel hoarsely

challenged the approaching foe! All

was still save the footsteps of the

soldiers, which sounded like the roar of the

distant surf, as it beats upon the

rock-bound coast.

"Ah, what is this! The silent and shattered walls of

Wagner all at once burst forth into a

blinding sheet of vivid light, as though

they had suddenly been transformed by some

magic power into the living, seething crater

of a volcano! Down came the whirlwind

of destruction along the beach with the

swiftness of lightning! How fearfully

the hissing shot, the shrieking bombs, the

whistling bars of iron, and the whispering

bullet struck and crushed through the dense

masses of our brave menuever shall forget

the terrible sound of that awful blast of

death, which swept down, shattered or dead,

a thousand of our men. Not a shot had

missed its aim. Every bolt of steel,

every globe of iron and lead, tasted of

human blood.

" 'Forward! ' shouted the undaunted Putnam, as the

column wavered and staggered like a giant

stricken with death.

" ' Steady, my boys! ' murmured the brave leader,

General Strong, as cannon-shot

dashed him, maimed and bleeding, into the

sand.

"In a moment the column recovered itself, like a

gallant ship at seawhen buried for an

instant under an immense wave.

"The ditch is reached; a thousand men leap into it,

clamber up the shattered ramparts, and

grapple with the foe, which yields and falls

back to the rear of the fort. Our men

swarm over the walls, bayoneting the

desperate rebel cannoneers. Hurrah!

the fort is ours!

"But now came another blinding blast from concealed

guns in the rear of the fort, and our men

went down by scores. Now the rebels

rally, and, re-enforced by thousands of the

chivalry, who have landed on the beach under

cover of darkness, unmolested by the guns of

the fleet. They hurl themselves with

fury upon the remnant of our brave band.

The struggle is terrific. Our supports

hurry up to the aid of their comrades, but

as they reach the ramparts they fire a

volley which strikes down many of our men.

Fatal mistake! Our men rally once

more; but, in spite of an heroic resistance,

they are forced back again to the edge of

the ditch. Here the brave Shaw, with

scores of his black warriers, went down,

fighting desperately. Here Putnam met

his death wound, while cheering and urging

on the overpowered Phalanx men.

"What fighting, and what fearful carnage! Hand to

hand, breast to breast! Here, on this

little strip of land, scarce bigger than the

human hand, dense masses of men struggled

with fury in the darkness; and so fierce was

the contest that the sands were reddened and

soaked with human gore.

"But resistance was vain. The assailants were

forced back again to

[Pg. 256]

the beach, and the rebels trained their

recovered cannon anew upon the retreating

survivors.

"What a fearful night was that, as we gathered up our

wounded heroes, and bore them to a place of

shelter! And what a mournful

morning, as the sun rose with his clear

beams, and revealed our terrible losses!

What a rich harvest Death had gathered to

himself during the short struggle!

Nearly two thousand of our men had fallen.

More than six hundred of our brave boys lay

dead on the ramparts of the fatal fort, in

its broad ditch, and along the beach at its

base. A flag of truce party went out

to bury our dead, but General

Beauregard they found had already buried

them, where they fell, in broad, deep

trenches."

Colonel Shaw,

the young and gallant commander of the 54th

Regiment, was formerly a member of the

famous 7th N. Y. Regiment. He was of

high, social and influential standing, and

in his death won destruction. The

confederates added to his fame and glory,

though unintentionally, by burying him with

his soldiers, or as a confederate Major

expressed the information, when a request

for the Colonel's body was made, "we have

buried him with his niggers! "

A poet has immortalized the occurrence and the gallant

Shaw thus:

'They

buried him with his niggers!'

Together they fought and died.

There wan room for them all where

they laid him.

(The grave was deep and wide).

For his beauty and youth and valor,

Their patience and love and pain;

And at the last together

They shall be found again.

'They buried him with his niggers!'

Earth holds no prouder grave;

There in not a mausoleum

In the world beyond the wave.

That a nobler tale has hallowed,

Or a purer glory crowned.

Than the nameless trench where they

buried

The brave so faithful found. |

'They

buried him with his niggers I'

A wide grave should it be:

They buried more in that shallow

trench

Than human eye could see.

Aye, all the shames and sorrows

Of more than a hundred years

Lie under the weight of that

Southern soil

Despite those cruel sneers.

They buried him with his niggers!'

But the glorious souls set free

Are lending the van of the army

That fights for liberty.

Brothers in death, in glory

The same palm branches bear;

And the crown is as bright o'er the

sable brows

As over the golden hair. |

|

---------- |

Burled

with a band of brothers

Who for him would fain have died;

Buried with the gallant fellows

Who fell fighting by his side;

Buried with the men God gave him.

Those whom he was sent to save;

Buried with the martyr heroes.

He has found an honored grave.

Buried where his dust so precious

Makes the soil a hallowed spot;

Buried where by Christian patriot.

He shall never be forgot. |

Buried

in the ground accursed.

Which man's fettered feet have trod;

Buried where his voice still

speaketh.

Appealing for the slave to God;

Fare thee well, thou noble warrior.

Who in youthful beauty went

On a high and holy mission,

By the God of battles sent.

Chosen of him. 'elect and precious,'

Well didst thou fulfil thy part;

When thy country 'counts her

jewels,'

She shall wear thee on her heart." |

[Pg. 257]

The heroic courage displayed by the gallant Phalanx at

the assault upon Fort Wagner was not

surpassed by the Old Guard at Moscow.

Major-General Taliaferro

gives this confederate account of the

fight, which is especially interesting as it

shows the condition of affairs inside the

fort:

"On the night of the 14th the

monster iron-plated frigate New Iron sides,

crossed the bar and added her formidable and

ponderous battery to those destined for the

great effort of reducing the sullen

earthwork which barred the Federal advance.

There were now five monitors, the Ironsides

and a fleet of gunboats and monster hulks

grouped together and only waiting the signal

to unite with the land batteries when the

engineers should pronounce them ready to

form a cordon of flame around the devoted

work. The Confederates were prepared

for the ordeal. For for fear that

communications with the city and the

mainland, which was had by steamboat at

night to Cummings' Point should be

interrupted, rations and ordnance stores had

been accumulated, but there was trouble

about water. Some was sent from

Charleston and wells had been dug in the

sand inside and outside the fort, but it was

not good. Sand bags had been provided

and trenching tools supplied sufficient for

any supposed requirement.

"The excitement of the enemy in front after the 10th

was manifest to the Confederates and

announced an 'impending crisis.' It

became evident that some extraordinary

movement was at hand. The Federal

forces on James Island had been attacked on

the morning of the 16th by General

Hagood and caused to retire, Hagood

occupying the abandoned positions, and on

the 17th the enemy's troops were transferred

to Little Folly and Morris Islands. It

has been stated that the key to the signals

employed by the Federals was in possession

of General Taliaferro at this

time, and he was thus made acquainted with

the intended movement and put upon his

guard. That is a mistake. He had

no such direct information, although it is

true that afterwards the key was discovered

and the signals interpreted with as much

ease as by the Federals themselves.

The 18th of July was the day determined upon

by the Federal commanders for the grand

attempt which, if successful, would level

the arrogant fortress and confuse it by the

mighty power of their giant artillery with

the general mass of surrounding sand hills,

annihilate its garrison or drive them into

the relentless ocean, or else consign them

to the misery of hostile prisons.

"The day broke beautifully, a gentle breeze slightly

agitated the balmy atmosphere, and with

rippling dimples beautified the bosom of

the placid sea. All nature was serene

and the profoundest peace held dominion over

all the elements. The sun, rising with

the early splendors of his midsummer glory,

burnished with golden tints the awakening

ocean, and flashed his reflected light back

from the spires of the beleag-

[Pg. 258]

uered city into the eves of those who stood

pausing to gather strength to spring upon

her, and of those who stood at bay to battle

for her safety. Yet the profound

repose was undisturbed; the early hours of

that fair morning hoisted a flag of truce

between the combatants which was respected

by both. But the tempest of fire which

was destined to break the charm of nature,

with human thunders then unsurpassed in war,

was gathering in the south. At about

half-past 7 o'clock the ships of war moved

from their moorings, the iron leviathan the

Ironsides, an Agamemnon among ships, leading

and directing their movements, then monitor

after monitor, and then wooden flagships.

Steadily and majestically they marched;

marched as columns of men would march,

obedient to commands, independent of weaves

and winds, mobilized by steam and science to

turn on a pivot and manoeuvre as the

directing mind required them; they halted in

front of the fort; they did not anchor as

Sir Peter Parker's ships had done near a

hundred years before in front of Moultrie,

which was hard by and frowning still at her

ancient enemies of the ocean. They

halted and waited for word of command to

belch their consuming lightnings out upon

the foe. On the laud, engineering

skill was satisfied and the deadly exposure

for details for labor was ended; the time

for retaliation had arrived when the defiant

shots of the rebel batteries would be

answered; the batteries were unmasked; the

cordon of fire was complete by land and by

sea; the doomed fort was encircled by guns.

"The Confederates watched from the ramparts the

approach of the fleet and the unmasking of

the guns, and they knew that the moment had

arrived in which the problem of the capacity

of the resistant power of earth and sand to

the forces to which science so far developed

in war could subject them was to be solved

and that Battery Wagner was to be that (lay

the subject of the crucial test. The

small armament of the fort was really

inappreciable in the contest about to be

inaugurated. There was but one gun

which could be expected to be of much avail

against the formidable naval power which

would assail it and on the land side few

which could reach the enemy's batteries.

"When those guns were knocked to pieces and

silenced there was nothing loft but passive

resistance, but the Confederates, from the

preliminary tests which had been applied,

had considerable faith in the capacity of

sand and earth for passive resistance.

"The fort was in good condition, having been materially

strengthened since the former assault by the

indefatigable exertions of Colonel

David Harris, chief engineer, and

his valuable assistant, Captain

Barnwell. Colonel Harris

was a Virginian, ex-officer of the army of

the United States and a graduate of West

Point, who had some years before retired

from the service to prosecute the profession

of civil engineering. Under a tempest

of shells he landed during the fiercest

period of the bombardment at Cummings'

Point, and made his way through the field of

fire to the beleaguered fort to inspect his

condition and to inspire the garrison by his

heroic courage and his confidence in its

strength. Escaping all the dangers of

war, he fell a victim to yellow fever in

Charleston, be-

[Pg. 259]

loved and honored by all who had ever known

him. The heavy work imposed upon the

garrison in repairs and construction, as

well as the strain upon the system by

constant exposure to the enemy's fire, had

induced General Beauregard to adopt

the plan of relieving the garrison every few

days by fresh troops. The objection to

this was that the new men had to be

instructed and familiarized with their

duties; but still it was wise and necessary,

for the same set of officers and men, if

retained any length of time, would have been

broken down by the arduous service required

of them. The relief was sent by

regiments and detachments, so there was

never an entirely new body of men in the

works.

"The garrison was estimated at one thousand seven

hundred aggregate. The staff of

General Taliaferro consisted of

Captain Twiggs, Quartermaster General;

Captain W. T. Taliaferro, Adjutant

General; Lieutenants H. C.

Cunningham and Magyck, Ordnance

Officers; Lieutenants Meade

and Stoney, Aides-de-Camp; Major

Holcombe; Captain Burke,

Quartermaster, and Habersham,

Surgeon-in-Chief; Private Stockman of

McEnery's Louisiana Battalion, who

had been detailed as clerk because of his

incapacity for other duty from most

honorable wounds, acted also in capacity of

aid.

The Charleston Battalion was assigned to

that part of the work which extended from

the Sally port or Lighthouse Inlet creek

around to the left until it occupied part of

the face to the south, including the western

bastion; the Fifty-first North Carolina

connected with these troops on the left and

extended to the southeast bastion; the rest

of the work was to be occupied by the

Thirty-first North Carolina Regiment, and a

small force from that regiment was detailed

as a reserve, and two campanies of

the Charleston Battalion were to occupy

outside of the fort the covered way spoken

of and some sand-hills by the seashore; the

artillery was distributed among the several

gun-chambers and the light pieces posted on

a traverse outside so as to sweep to sea

face and the right approach. The

positions to be occupied were well known to

every officer and man and had been verified

repeatedly by day and night, so there was no

fear of confusion, mistake or delay in the

event of an assault. The troops of

course were not ordered to these positions

when at 6 o'clock it was evident a furious

bombardment was impending, but, on the

contrary, to the shelter of the bomb-proofs,

sand-hills and parapet; a few sentinels or

videttes were detailed and the gun

detachments only ordered to their pieces.

"The Charleston Battalion perferred the freer air of

the open work to the stifling atmosphere of

the bomb-proofs and were permitted to

shelter themselves under the parapet and

traverses. Not one of that heroic band

entered the opening of a bomb-proof during

that frightful day. The immense

superiority of the enemy's artillery was

well understood and appreciated by the

Confederate commander, and it was clear to

him that his policy was to husband his

resources and preserve them as best he could

for the assault, which it was reasonable to

expect would occur during the day. He

recognized the fact that his guns were only

[Pg. 260]

defensive and he had little or no offensive

power with which to contend with his

adversaries. Acting on his conviction

he had the light guns dismounted and covered

with sand bags, and the same precaution was

adopted to preserve some of the shell guns

or fixed carriages. The propriety of

this determination was abundantly

demonstrated in the end.

"About a quarter past 8 o'clock the storm broke, ship

after ship and battery after battery, and

then apparently all together, vomited forth

their horrid flames and the atmosphere was

filled with deadly missiles. It is

impossible for any pen to describe or for

anyone who was not an eye-witness to

conceive the frightful grandeur of the

spectacle. The writer has never had

the fortune to read any official Federal

report or any other account of the

operations of this day except an extract

from any other account of the operations of

this day except an extract from the graphic

and eloquent address of the Rev. Mr.

Dennison, a chaplain of one of the

Northern regiments, delivered on its

nineteenth anniversary at Providence, R. I.

He says: 'Words cannot depict the thunder,

the smoke, and lifted sand and the general

havoc which characterized that hot summer

day. What a storm of iron fell on that

island; the roar of the guns was incessant;

how the shots ploughed the sand banks and

the marshes; how the splinters flew from the

Beacon House; how the whole island smoked

like a furnace and trembled as from an

earthquake.'

"if that was true outside of Wagner it is easy to

conceive how intensified the situation was

within its narrow limits towards which every

hostile gun was pointed. The sand came

down in avalanches; huge vertical shells and

those rolled over by the ricochet shots from

the ships, buried themselves and then

exploded, rending the earth and forming

great craters, out of which the sand and

iron fragments few high in the air. It

was a fierce sirocco freighted with iron as

well as sand. The sand flew over from

the seashore, from the glacis, from the

exterior slope, from the parapet, as it was

ploughed up and lifted and driven by

resistless force now in spray and now almost

in waves over into the work, the men

sometimes half buried by the moving mass.

The chief anxiety was about the magazines.

The profile of the fort might be destroyed,

the ditch filled up, the traverses and

bomb-proof barracks knocked out of shape,

but the protecting banks of sand would still

afford their shelter; but if the coverings

of the magazines were blown away and they

became exposed, the explosion that would

ensue would lift fort and garrison into the

air and annihilate all in general chaos.

They were carefully watched and reports of

their condition required to be made at short

intervals during the day.

Wagner replied to the enemy, her 10-inch

columbiad alone to the ships, deliberately

at intervals of fifteen minutes, the other

guns to the land batteries whenever in

range, as long as they were serviceable.

The 32-pounder rifled guns was soon rendered

useless by bursting and within two hours

many other guns had been dismounted and

their carriages destroyed. Sumter,

Colonel Alfred Rhett in command, and

Gregg, under charge of Captain

Sesesne, with the Sullivan and James

Island batteries at long range, threw all

the power of their available metal at the

assail-

[Pg. 261]

ants and added their thunders to that

universal din; the harbor of Charlston was a

volcano. The want of water was felt,

but now again unconsciously the enemy came

to the assistance of the garrison, for water

was actually scooped from the craters made

in the sand by the exploded shells.

The city of Charleston was alive and aflame

with excitement; the bay, the wharves, the

steeples and streets filled with anxious

spectators looking across the water at their

defenders, whom they could not succor.

"At 2 o'clock the flag halliards were cut by a shot and

the Confederate garrison flag was blown over

into the fort; there was an instant race for

its recovery through the storm of missiles,

over the broken earth and shells and

splinteres which lined the parade.

Major Ramsey, Sergeant Shelton and

private Flinn of Charleston Battalion,

and Lieutenant Riddick,of the

Sixty-third Georgia, first reached it and

bore it back in triumph to the flagstaff,

and at the same moment Captain Barnwell

of the engineers, seized a battle-flag, and

leaping on the ramparts, drove the staff

into the sand. This flag was again

shot away, but was again replaced by

Private Gaillard, of the Charleston

Battalion. These intrepid actions,

emulating in a higher degree the conduct of

SErgeant Jasper at Moultrie during

the Revolution, were cheered by the command

and inspired them with renewed courage.

"The day wore on; thousands upon thousands of shells

and round shot, shells loaded with balls,

shells of guns and shells of mortars,

percussion shells, exploding upon impact,

shells with graded fuses - every kind

apparently known to the arsenals of war

leaped into and around the doomed

fort, yet there was no cessation; the sun

seemed to stand still and the long midsummer

day to know no right. Some men were

dead and no scratch appeared on their

bodies; the concussion had forced the breath

from their lungs and collapsed them into

corpses. Captain Twiggs, of the

staff, in executing some orders was found

apparently dead. He was untouched, but

lifeless, and only strong restoratives

brought him back to animation, and the

commanding officer was buried knee-deep in

sand and had to be rescued by spades from

his imprisonment. The day wore on,

hous followed hours of anxiety and grim

endurance, but no respite ensued. At

last night came; not however, to herald a

cessation of the strife, but to usher in a

conflict still more terrible. More

than eleven hours had passed. The fort

was torn and mutilated; to the outside

observer it was apparently powerless,

knocked to pieces and pounded out of shape,

the outline changed, the exterior slope full

of gaping wounds, the ditch half filled up,

but the interior still preserved its form

and its integrity; scarred and defaced it

was yet a citadel which, although not

offensive, was defiant.

It was nearly eight-o'clock at night, but still

twilight, when a calm came and the blazing

circle ceased to glow with flame. The

ominous pause was understood; it required no

signals to be read by those to whom they

were not directed to inform them that the

supreme moment to test the value of the

day's achievements was now at hand. It

meant nothing but assault. Dr.

Dennison says the assault was intended

to be

[Pg. 262]

a surprise. He over-estimates the

equanimity of the Confederate commander if

he supposes that that bombardment, which

would have waked the dead, had lulled him

into security and repose. The buried

cannon were at once exhumed, the guns

remounted and the garrison ordered to their

appointed posts. The Charleston

Battalion were already formed and in

position; they had nestled under the parapet

and stood ready in their places. The

other troops with the exception of part of

one regiment, responded to the summons with

extraordinary celerity, and the echoes of

the Federal guns had hardly died away before

more than three-fourths of the ramparts were

lined with troops ; one gap remained

unfilled; the demoralized men who should

have filled it clung to the bomb-proofs and

stayed there. The gallant Colonel

Simpkins called his men to the

gun-chambers wherever guns existed.

De Pass, with his light artillery

on the traverse to the left, his guns

remounted and untouched, stood ready, and

Colonel Harris moved a howitzer

outside the fort to the right to deliver an

enfilade fire upon the assailants.

"The dark masses of the enemies columns, brigade after

brigade, were seen in the fading twilight to

approach; line after line was formed and

then came the rush. A small creek made

in on the right of the fort and intercepted

the enemy's left attack; they did not know

it, or did not estimate it. Orders

were given to Gaillard to hold his

fire and deliver no direct shot. It

was believed the obstacle presented by the

creek would confuse the assailants, cause

them to incline to the right and mingle

their masses at the head of the obstacle and

thus their movements would be obstructed.

It seemed to have the anticipated effect and

the assaulting columns apparently jumbled

together at this point were met by the

withering volleys of McKethan's

direct and Gaillard's cross-fire and

by the direct discharge of the shell guns,

supplemented by the frightful enfilading

discharges of the lighter guns upon the

right and left. It was terrible, but

with an unsurpassed gallantry the Federal

soldiers breasted the storm and rushed

onward to the glacis.

"The Confederates, not fourteen hundred strong, with

the tenacity of bull dogs and a fierce

courage which was roused to madness by the

frightful inaction to which they had been

subjected, poured from the ramparts and

embrasures sheets of flame and a tempest of

lead and iron, yet their intrepid assailants

rushed on like the waves of the sea by whose

shore they fought. They fell by

hundreds, but they pushed on, reeling under

the frightful blasts that almost blew them

to pieces, some up to the Confederate

bayonets. The southeast bastion was

weakly defended, and into it a considerable

body of the enemy made their way but they

were caught in a trap, for they could not

leave it. The fight continued; but it

was impossible to stem the torrent of deadly

missiles which poured out from the fort, the

reflux of that terrible tide which had

poured in all day, and the Federals

retreated, leaving near a thousand dead

around the fort.

"There was no cessation of the Confederate fire.

Sumter and Gregg threw their

shells along with those of Wagner upon the

retiring foe; nor

[Pg. 263]

was the conflict over in the fort

itself. The party which had gained

access by the salient next the sea could not

escape. It was certain death to

attempt to pass the line of concentrated

fire which swept the faces of the work, and

they did not attempt it; but they would not

surrender, and in desperation kept up a

constant fire upon the main body of the

fort. The Confederates called for

volunteers to dislodge them a summons which

was promptly responded to by Major

McDonald, of the Fifty-first North

Carolina, and by Captain Rion,

of the Charleston Battalion,

with the requisite number of men.

Rion's company was selected, and the

gallant Irishman, at the head of his

company, dashed at the reckless and insane

men, who seemed to insist upon immolation.

The tables were now singularly turned; the

assailants had become the assailed and they

held a fort within the fort, and were

protected by the traverses and gun chambers,

behind which they fought. Rion

rushed at them, but he fell, shot outright,

with several of his men, and the rest

recoiled. At this time General

Hagood reported to General

Taliaferro with Colonel Harrison's

splendid regiment, the Thirty-second

Georgia, sent over by Beauregard to

his assistance as soon as a landing could be

effected at Cummings' Point. These

troops were ordered to move along on the

traverses and bomb-proofs, and to plunge

their concentrated fire over the stronghold.

Still, for a time, the enemy held out, but

at last they cried out and surrendered.

"The carnage was frightful. It is believed the Federals

lost more men on that eventful night than

twice the entire strength of the Confederate

garrison. The Confederates lost eight

killed and twenty wounded by the bombardment

and about fifty killed and one hundred and

fifty wounded altogether from the

bombardment and assault. Among the

killed were those gallant officers,

Lieutenant Colonel Simkins

and Major Ramsey and among the

wounded Captains DePass and

Twiggs, of the staff, and Lieutenants

Storey (Aide-de-Camp), Power

and Watties. According to the

statement of Chaplain Dennison

the assaulting columns in two brigades,

commanded by General Strong

and Colonel Putnam (the

division under General Seymour),

consisted of the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts,

Third and Seventh New Hampshire, Sixth

Connecticut and One Hundredth New York, with

a reserve brigade commanded by General

Stephenson. One of the

assaulting regiments was composed of negroes

(the Fifty-fourth Massachusetts) and to it

was assigned the honor of leading the white

columns to the charge. It was a dearly

purchased compliment. Their Colonel

(Shaw) was killed upon the parapet

and the regiment almost annihilated,

although the Confederates in the darkness

could not tell the color of their

assailants. Both the brigade

commanders were killed as well as Colonel

Chatfield.

"The same account says: 'We lost 55 officers and

585 men, a total of 640, one of the choicest

martyr rolls of the war.' By 'lost,'

'killed' is supposed to be meant, but still

that number greatly falls short of the

number reported by the Confederates to have

been buried on the 19th by them and by their

own friends under a flag of truce.

These reports show

[Pg. 264]

that 800 were buried, and as a number

were taken prisoners, and it is fair to

estimate that three were wounded to one

killed, the total loss of the Federals

exceeded 3,000. The writer's official

report estimates the Federal loss at not

less than 2,000; General Beauregard's

at 3,000. The Federal official reports

have not been seen.

"The limits prescribed for this paper would be exceeded

if any account of the remaining forty-eight

days of the heroic strife on Morris Island

were attempted. It closes with the

repulse of the second assault, and it is a

fit conclusion to render the homage due to

the gallantry of the contestants by quoting

and adopting the language of Dr.

Dennison's address: 'The truest courage

and determination was manifested on both

sides on that crimson day at that great

slaughter-house, Wagner.' "

It was no longer a question of doubt as to

the valor of Northern negroes. The

assault on Fort Wagner completely removed

any prejudice that had been exhibited toward

negro troops in the Department of the South.

General Gillrnore immediately

issued an order forbidding any distinction

to be made among troops in his command.

So that while the black Phalanx had lost

hundreds of its members, it nevertheless won

equality in all things save the pay.

The Government refused to place them on a

footing even with their Southern brothers,

who received $7 per month and the white

troops $13. However, they were not

fighting for pay, as "Stonewall" of Company

C argued, but for the "freedom of our

kin" Nobly did they do this, not only at

Wagner, as we have seen, but in the battles

on James Island, Honey Hill, Olustee and at

Boykin's Mill.

In the winter of 1864, the troops in the Department of

the South lay encamped on the islands in and

about Charleston harbor, resting from their

endeavors to drive

the confederates from their strongholds.

The city was five miles away in the

distance. Sumter, grim, hoary and in

ruins, yet defying the National authority,

was silent.

General Gillmore was in

command of the veteran legions of the 10th

Army Corps, aided by a powerful fleet of

ironclads and other war vessels. There

laid the city of Charleston, for the time

having a respite. General Gillmore was

giving rest to his troops, before he began

again to throw Greek tire into the city and

batter the walls of its defences. The

shattered ranks of the Phalanx soldiers

rested in the

[Pg. 265]

midst of thousands of their white

comrades-in-arms, to whom they nightly

repeated the story of the late terrible

struggle. The solemn sentry pacing the

ramparts of Fort Wagner night and day, his

bayonet glittering in the rays of the sun or

in the moonlight, seemed to be guarding the

sepulchre of Col. Shaw and

those who fell beside him within the walls

of that gory fort, and who were buried where

they fell. Only those who have lived

in such a camp can appreciate the stories of

hair-breadth escapes from hand-to-hand

fights.

The repose lasted until January, when an important

movement took place for the permanent

occupation of Florida. The following

account, written by the author of this book,

was published in " The Journal," of Toledo,

O.:

"The twentieth day of

February, 1864, was one of the most

disastrous to the Federal arms, and to the

administration of President

Lincoln, in the annals of the war for

the union. Through private advice

Mr. Lincoln had received

information which led him to believe that

the people in the State of Florida, a large

number of them, at least, were ready and

anxious to identify the State with the cause

of the Union, and he readily approved of the

Federal forces occupying the State, then

almost deserted by the rebels. Gen.

Gillmore, commanding the Department

of the South had a large force before

Charleston, S. C, which had been engaged in

the capture of Fort Wagner and the

bombardment of the city of Charleston, and

the reduction of Sumter.

"These objects being accomplished, the army having

rested several months, Gen.

Gillmore asked for leave to undertake

such expeditions within his Department as he

might think proper. About the middle

of December, 1861, the War Department

granted him his request, and immediately he

began making preparations for an expedition,

collecting transports, commissary stores,

drilling troops, etc., etc.

"About the 1st of January, 1864, General

Gillmore wrote to the

General-in-Chief, Halleck, that he was

about to occupy the west bank of St. Johns

river, with the view (1st) to open an outlet

to cotton, lumber, etc., (2d) to destroy one

of the enemy's sources of supplies, (3d) to

give the negroes opportunity of enlisting in

the army, (4th) to inaugurate measures for

the speedy restoration of Florida to the

Union.

"In accordance with instructions from President

Lincoln received through the

assistant Adjutant General, Major J. H.

Hay, who would accompany the expedition,

on the 5th of February the troops began to

embark under the immediate command of

General Truman Seymour, on

board of twenty steamers and eight

schooners, consisting of the following

regiments, numbering in all six thousand

troops, and under convoy

[Pg. 266]

of the gunboat Norwich:

"40th Massachusetts Mounted Infantry, Col. Guy V.

Henry.

"7th Connecticut, Col. J. R. Hawley.

"7th New

Hampshire, Col. Abbott.

"47th, 48th and

115th New York, Col. Barton's

command.

"The Phalanx regiments were: 8th Pennsylvania, Col.

Fribley; 1st North Carolina, Lt.-Col.

Reed; 54th Massachusetts, Col.

Hallowell; 2d South Carolina, Col. Beecher;

55th Massachusetts, Col. Hartwell, with

three batteries of white troops, Hamilton's,

Elder's and Langdon's. Excepting the

two last named regiments, this force landed

at Jacksonville on the 7th of February, and

pushed on, following the 40th Massachusetts

Mounted Infantry, which captured by a bold

dash Camp Finnigan, about seven miles from

Jacksonville, with its equipage, eight

pieces of artillery, and a number of

prisoners. On the 10th, the whole

force had reached Baldwin, a railroad

station twenty miles west of Jacksonville.

There the army encamped, except Col.

Henry's force, which continued its

advance towards Tallahassee, driving a small

force of Gen. Finnegan's

command before him. This was at the

time all the rebel force in east Florida.

On the 18th Gen. Seymour,

induced by the successful advance of Col.

Henry, lead his troops from Baldwin with ten

days' rations in their haversacks, and

started for the Suwanee river, about a

hundred and thirty miles from Baldwin

station, leaving the 2d South Carolina and

the 55th Massachusetts Phalanx regiments to

follow. After a fatiguing march the

column, numbering about six thousand,

reached Barbour's Station, on the Florida

Central Railroad, twenty miles from Baldwin.

Here the command halted and bivouaced, the

night of the 19th, in the woods bordering

upon a wooded ravine running off towards the

river from the railroad track.

"It is now nineteen years ago, and I write

from memory of a night long to be

remembered. Around many a Grand Army

Camp-fire in the last fifteen years this

bivouac has been made the topic of an

evening's talk. It was attended with no

particular hardship. The weather was

such as is met with in these latitudes, not

cold, not hot, and though a thick vapory

cloud hid the full round moon from early

eventide until the last regiment filed into

the woods, yet there was a halo of light

that brightened the white, sandy earth and

gave to the moss-laden limbs of the huge

pines which stood sentry-like on the

roadside the appearance of a New England

grove on a frosty night, with a shelled road

leading through it.

"It was well in the night when the two Phalanx regiments

filed out of the road into the woods,

bringing up the rear of the army, and took

shelter under the trees from the falling

dew. Amid the appalling stillness that

reigned throughout the encampment, except

the tramp of feet and an occasional

whickering of a battery horse, no sound

broke the deep silence. Commands were

given in an undertone and whispered along

the long lines of weary troops that lay

among the trees and the underbrush of the

pine forest. Each soldier lay with his

musket beside him, ready to

[Pg. 267]

spring to his feet and in

line for battle, for none knew the moment

the enemy, like a tiger, would pounce upon

them. It was a night of intense

anxiety, shrouded in mystery as to what

to-morrow would bring. The white and

black soldier in one common bed lay in

battle panoply, dream mg their common dreams

of home and loved ones.

"Here lay the heroic 54th picturing to themselves the

memorable nights of July 17 and 18, their

bivouac on the beach and their capture of

Fort Wagner and the« terrible fate of their

comrades. They were all veteran troops save

the 8th Pennsylvania, which upon many hard

fought fields had covered themselves with

gallant honor in defense of their country's

cause, from Malvern Hill to Morris Island.

It was in the gray of the next morning that Gen.

Seymour's order aroused the command.

The men partook of a hastily prepared cup of

coffee and meat and hard-tack from their

haversacks. At sunrise the troops took

up the line of march, following the railroad

for Lake City. Col. Henry,

with the 40th Massachusetts Mounted Infantry

and Major Stevens' independent

battalion of Massachusetts cavalry, led the

column. About half-past one o'clock

they reached a point where the country road

crossed the railroad, about two miles east

of Olustee, and six miles west of Sanderson,

a station through which the troops passed

about half-bast eleven o'clock. As the head

of the column reached the crossing the rebel

pickets fired and fell back upon a line of

skirmishers, pursued by Col. Henry's

command. The enemy's main force was

supposed to be some miles distant from this

place, consequently General Seymour had not

taken the precaution to protect his flanks,

though marching through an enemy's country.

Consequently he found his troops flanked on

either side.

"Col. Henry drove the skirmishers back

upon their main forces, which were strongly

posted between two swamps. The

position was admirably chosen their

right rested upon a low, slight earthwork,

protected by rifle-pits, their center was

defended by an impassable swamp, and on

their left was a cavalry force drawn up on a

small elevation behind the shelter of a

grove of pines. Their camp was

intersected by the rail road, on which was

placed a battery capable of operating

against the center and left of the advancing

column, while a rifle gun, mounted on a

railroad flat, pointed down the road in

front.

"Gen. Seymour, in order to attack

this strongly fortified position, had

necessarily to place his troops between the

two swamps, one in his front, the other in

the rear. The Federal cavalry,

following up the skirmishers, had attacked

the rebel right and were driven back, but

were met by the 7th New Hampshire, 7th

Connecticut, a regiment of the black Phalanx

(8th Pennsylvania), and Elder's battery of

four and Hamilton's of six pieces.

This force was hurled against the rebel

right with such impetuosity that the

batteries were within one hundred yards of

the rebel line of battle before they knew

it. However, they took position, and

supported by the Phalanx regiment, opened a

vigorous fire upon the rebel

earthworks. The Phalanx regiment

advanced within twenty or

[Pg. 268]

thirty yards of the enemy's rifle-pits, and

poured a volley of minie balls into the very

faces of those who did not fly on their

approach.

"The 7th Connecticut and the 7th New Hampshire, the

latter with their seven-shooters, Spencer

repeaters, Col. Hawley,

commanding, had taken a stand further to the

right of the battery, and were hotly

engaging the rebels. The Phalanx

regiment (8th), after dealing out two rounds

from its advanced position, finding the

enemy's force in the center preparing to

charge upon them, fell back under cover of

Hamilton's battery, which was firing

vigorously and effectively into the rebel

column. The 7th Connecticut and New

Hampshire about this time ran short of

ammunition, and Col. Hawley,

finding the rebels outnumbered his force

three to one, was about ordering Col.

Abbott to fall back and out of the

concentrated fire of the enemy pouring upon

his men, when he observed the rebels coming

in for a down upon his column.

"Here they come like tigers; the Federal column wavers

a little; it staggers and breaks, falling

back in considerable disorder! Col.

Hawley now ordered Col.

Fribley to take his Phalanx Regiment,

the 8th, to the right of the battery and

check the advancing rebel force. No

time was to be lost, the enemy's

sharpshooters had already silenced two of

Hamilton's guns, dead and dying men and

horses lay in a heap about them, while at

the remaining four guns a few brave

artillerists were loading and fixing their

pieces, retarding the enemy in his onward

movement.

"Deficient in artillery, they had not been able to

check the Federal cavalry in its dash, but

the concentrated fire from right to center

demoralized, and sent them galloping over

the field wildly. Col.

Fribley gave the order by the right

flank, double quick! and the next moment the

8th Phalanx swept away to the extreme right

in support of the 7th New Hampshire and the

7th Connecticut. The low, direct aim

of the enemy in the rifle-pits, his Indian

sharp-shooters up in the trees, had ere now

so thinned the ranks of Col.

Hawley's command that his line was gone,

and the 8th Phalanx met the remnant of his

brigade as it was going to the rear in

complete disorder. The rebels ceased

firing and halted as the Phalanx took

position between them and their fleeing

comrades. They halted not perforce,

but apparently for deliberation, when with

one fell swoop in the next moment they swept

the field in their front.

"The Phalanx did not, however, quit the field in a

panic-stricken manner but fell hastily back

to the battery, only to find two of the guns

silent and their brave workers and horses

nearly all of them dead upon the field.

With a courage undaunted, surpassed by no

veteran troops on any battle-field, the

Phalanx attempted to save the silent guns.

In this effort Col. Fribley

was killed, in the torrent of rebel bullets

which fell upon the regiment. It held

the two guns, despite two desperate charges

made by the enemy to capture them, but the

stubbornness of the Phalanx was no match for

the ponderous weight of their enemy's

column, their sharpshooters and artillery

mowing down ranks of their comrades at every

volley. A grander spectacle was never

witnessed than that which this regiment gave

of gallant courage. They left their

guns

[Pg. 269]

only when their line officers and three

hundred and fifty of their valient soldiers

were dead upon the field, the work of an

hour and a half. The battery lost

forty of its horses and four of its brave

men. The Phalanx saved the colors of

the battery with its own. Col.

Barton's brigade, the 47th, 48th and

115th New York, during the fight on the

right had held the enemy in the front and

center at bay, covering Elder's battery, and

nobly did they do their duty, bravely

maintaining the reputation they had won

before Charleston, but like the other

troops, the contest was too unequal.

The rebels outnumbered them five to one, and

they likewise gave way, leaving about a

fourth of their number upon the field, dead

and wounded.

"Col. Montgomery's brigade, comprising

two Phalanx regiments, 54th Massachusetts

and 1st North Carolina, which had been held

in reserve about a mile down the road, now

came up at double-quick. They

were under heavy marching orders, with ten

days' rations in their knapsacks, besides

their cartridge boxes they carried ten

rounds in their overcoat pockets. The

road was sandy, and the men often found

their feet beneath the sand, but with their

wonted alacrity they speed on up the road,

the 54th leading in almost a locked running

step, followed closely by the 1st North

Carolina. As they reached the road

intersected by the railroad they halted in

the rear of what remained of Hamilton's

battery, loading a parting shot.

The band of the 54th took position on the

side of the road, and while the regiments

were unstringing knapsacks as coolly as if

about to bivouac, the music of the band

burst out on the sulphureous air, amid the

roar of artillery, the rattle of musketry

and the shouts of commands, mingling its

soul-stirring strains with the deafening

yells of the charging columns, right, left,

and from the rebel center. Thus on the

very edge of the battle, nay, in the battle,

the Phalanx band poured out in heroic

measures 'The Star Spangled Banner.'

Its thrilling notes, souring above the

battles' gales, aroused to new life and

renewed energy the panting, routed troops,

flying in broken and disordered ranks from

the field. Many of them halted, the New York

troops particularly, and gathered at the

battery again, pouring a deadly volley into

the enemy's works and ranks. The 54th

had but a moment to prepare for the task.

General Seymour rode up and

appealed to the Phalanx to check the enemy

and save the army from complete and total

annihilation. Col.

Montgomery gave Col. Hallowell

the order 'Forward,' pointing to the left,

and away went the 54th Phalanx regiment

through the woods, down into the swamp,

wading up to their knees in places where the

water reached their hips; yet on they went

till they reached terra firma. Soon

the regiment stood in line of battle, ready

to meet the enemy's advancing cavalry,

emerging from the extreme left.

" 'Hold your fire !' the order ran down the line.

Indeed, it was trying. The cavalry had

halted but the enemy, in their rifle-pits in

the center of their line, poured volley

after volley into the ranks of the Phalanx,

which it stood like a wall of granite,

holding at bay the rebel cavalry hanging on

the edge of a pine grove. The 1st Phalanx

regiment

[Pg. 270]

entered the field in front, charged the

rebels in the centre of the line, driving

them into their rifle-pits, and then for

half an hour the carnage became frightful.

They had followed the rebels into the very

jaws of death, and now Col. Reid

found his regiment in the enemy's enfilading

fire, and they swept his line. Men

fell like snowflakes. Driven by this

terrific iire, they fell back. The

54th had taken ground to the right, lending

whatever of assistance they could to their

retiring comrades, who were about on a line

with them, for although retreating, it was

in the most cool and deliberate manner, and

the two regiments began a firing at will

against which the rebels, though

outnumbering them, could not face.

Thus they held them till long after sunset,

and firing ceased.

"The slaughter was terrible; the Phalanx lost about 800

men, the white troops about 600. It

was Braddock's defeat after the lapse

of a century."

The rout was complete; the army was not only

defeated but beaten and demoralized.

The enemy had succeeded in drawing it into a

trap for the purpose of annihilating it.

Seymour had advanced, contrary to the

orders given him by General

Gillmore, from Baldwin's Station, where

he was instructed to intrench and await

orders. Whether or not he sought to

retrieve the misfortunes that had attended

him in South Carolina, in assaulting the

enemy's works, is a question which need not

be discussed here. It is only

necessary to show the miserable

mismanagement of the advance into the

enemy's country. The troops were

marched into an ambuscade, where they were

slaughtered by the enemy at will. Even

after finding his troops ambuscaded, and

within two hundred yards of the confederate

fortifications, General Seymour

did not attempt to fall back and form a line

of battle, though he had sufficient

artillery, but rushed brigade after brigade

up to the enemy's guns, only to be mowed

down by the withering storm of shot.

Each brigade in turn went in as spirited as

any troops ever entered a fight, but

stampeded out of it maimed, mangled and

routed. At sunset the road, foot-paths and

woods leading back to Saunders' Station, was

full of brave soldiers hastening from the

massacre of their comrades, in their

endeavor to escape capture. At about

nine o'clock that night, what remained of

the left column, Colonel

Montgomery's brigade, consisting of the

54th and 35th Phalanx Regiments, and a bat

[Pg. 271]

CHARGE OF THE PHALANX.

[Pg. 272] - BLANK

[Pg. 273] -

DEPARTMENT OF THE SOUTH. -

tery, arrived at the Station, and reported

the confederates in hot pursuit.

Instantly the shattered, scattered troops

fled to the roads leading to Barber's, ten

miles away, with no one to command.

Each man took his own route for Barber's,

leaving behind whatever would encumber him,

arms, ammunition, knapsacks and cartridge

boxes; many of the latter containing forty

rounds of cartridges. It was long past

midnight when Barber's was reached,

and full day before the frightened mob

arrived at the Station. At sunrise on

the morning of the 21st, the scene presented

at Barber's was sickening and sad.

The wounded lay everywhere, upon the ground,

huddled around the embers of fagot tires,

groaning and uttering cries of distress.

The surgeons were busy relieving, as best

they could, the more dangerously wounded.

The foot-sore and hungry soldiers sought out

their bleeding and injured comrades and

placed them upon railroad flats, standing

upon the tracks, and when these were loaded,

ropes and strong vines were procured and

fastened to the flats. Putting

themselves in the place of a locomotive,

several of which stood upon the track at

Jacksonville, the mangled and mutilated

forms of about three hundred soldiers were

dragged forward mile after mile. Just

in the rear, the confederates kept up a fire

of musketry, as though to hasten on the

stampede. It was well into the night

when the train reached Baldwin's, where it

was thought the routed force would occupy

the extensive work encircling the station,

but they did not stop; their race was

continued to Jacksonville. At

Baldwin's an agent of the Christian

Commission gave the wounded each two

crackers, without water. This over

with, the train started for Jacksonville,

ten miles further. The camp of

Colonel Beecher's command, 2nd

Phalanx Regiment, was reached, and here

coffee was furnished. At daylight the

train reached Jacksonville, where the

wounded were carried to the churches and

cared for. The battle and the retreat

had destroyed every vestige of distinction

based upon color. The troops during

the battle had fought together, as during

the stampede they had endured its horrors

together.

[Pg. 274]

The news of the battle and defeat reached

Beaufort the night of the 23rd of February.

It was so surprising that it was doubted,

but when a boat load of wounded men arrived,

all doubts were dispelled.

Colonel T. W. Higginson, who was at Beaufort at

the time with his regiment, (1st S. C.),

thus notes the reception of the news in his

diary, which we quote with a few comments

from his admirable book, "Army Life in a

Black Regiment":

" 'FEBRUARY 19TH.

" '

Not a bit of it! This morning the

General has ridden up radiant, has seen

General Gillmore, who has decided not

order us to Florida at all, nor withdraw any

of this garrison. Moreover, he says

that all which is intended in Florida is

done - that there will be no advance to

Tallahassee, and General Seymour will

establish a camp of instruction in

Jacksonville. Well, if that is all, it

is a lucky escape.

"We little dreamed that on that very day the march

toward Olustee was a beginning. The

battle took place next day, and I add one

more extract to show how the news reached

Beaufort.

" 'FEBRUARY 23, 1864.

" 'There was a sound of revelry by night at a ball in

Beaufort last night, in a new large building

beautifully decorated. All the

collected flags of the garrison hung round

and over us, as if the stars and stripes

were devised for an ornament alone.

The array of uniforms was such, that a

civilian became a distinguished object, much

more a lady. All would have gone

according to the proverbial marriage bell, I

suppose, had there not been a slight

palpable shadow over all of us from hearing

vague stories of a lost battle in Florida,

and from the thought that perhaps the very

ambulances in which we rode to the ball were

ours only until the wounded or the dead

might tenant them.

" 'General Gillmore only came, I

supposed, to put a good face upon the

matter. He went away soon, and

General Saxton went; then came a

rumor that the Cosmopolitan had actually

arrived with wounded, but still the dance

went on. There was nothing unfeeling

about it - one gets used to things, -

when suddenly, in the midst of the

'Lancers,' there came a perfect hush, the

music ceasing, a few surgeons went hastily

to and fro, as if conscience stricken (I

should think they might have been), and then

there 'waved a mighty shadow in,' as in

Uhland's 'Black Knight,' and as we all stood

wondering we were aware of General Saxton

who strode hastily down the hall, his pale

face very resolute, and looking almost sick

with anxiety. He had just been on

board the steamer; there were two hundred

and fifty wounded men just arrived, and the

ball must end. Not that there was anything

for us to do, but the revel was mis-timed,

and must be ended; it was wicked to be

dancing with such a scene of suffering near

by.

[Pg. 275] - BLANK

[Pg. 276]

PHALANX RIVER PICKETS DEFENDING THEMSELVES

Federal picket boat near Fernandina, Fla.,

attached by Confederate sharpshooters

stationed in the trees on the banks.

[Pg. 277]

" 'Of course the ball was instantly broken up,

though with some murmurings and some

longings of appetite, on the part of some,

toward the wasted supper.

" 'Later, I went on board the boat. Among the

long lines of wounded, black and white

intermingled, there was the wonderful quiet

which usually prevails on such occasions.

Not a sob nor a groan, except from those

undergoing removal. It is not

self-control, but chiefly the shock to the

system produced by severe wounds, especially

gunshot wounds, and which usually keeps the

patient stiller at first than at any later

time.

" 'A company from my regiment waited on the wharf, in

their accustomed dusky silence, and I longed

to ask them what they thought of our Florida

disappointment now? In view of what

they saw, did they still wish we had been

there? I confess that in presence of

all that human suffering, I could not wish

it. But I would not have suggested any such

thought to them.

" 'I found our kind-hearted ladies, Mrs.

Chamberlin and Mrs. Dewhurst,

on board the steamer, but there was nothing

for them to do, and we walked back to camp

in the radiant moonlight; Mrs.

Chamberlin more than ever strengthened

in her blushing woman's philosophy, 'I don't

care who wins the laurels, provided we

don't!'

" 'FEBRUARY 29TH.

"'But for a few trivial cases of varioloid, we should

certainly have been in that disastrous

fight. We were confidently expected

for several days at Jacksonville, and the

commanding general told Hallowell that we,

being the oldest colored regiment, would

have the right of the line. This was

certainly to miss danger and glory very

closely.' "

At daybreak on the 8th of March, 1864, the

7th Regiment, having left Camp Stanton,

Maryland, on the 4th and proceeded to

Portsmouth, Va., embarked on board the

steamer "Webster" for the Department of the

South. Arriving at Hilton Head, the

regiment went into camp for a few days, then

it embarked for Jacksonville, Fla., at which

place it remained for some time, taking part

in several movements into the surrounding

country and participating in a number of

quite lively skirmishes. On the 27th

of June a considerable portion of the

Regiment was ordered to Hilton Head, where

it arrived on July 1st; it went from there

to James Island, where with other troops a

short engagement with the confederates was

had. Afterwards the regiment returned

to Jacksonville, Fla., remaining in that

vicinity engaged in raiding the adjacent

territory until the 4th of August, when the

regiment was

[Pg. 278]

ordered to Virginia, to report to the Army

of the Potomoc, where it arrived on Aug.

8th. The 55th Massachusetts Regiment

was also ordered to the Department of the

South. It left Boston July 21st, 1863,

on the steamer "Cahawba," and arrived at

Newbern on the 25th. After a few days

of rest, to recover from the effects of the

voyage, the regiment was put into active

service, and performed a large amount of

marching and of the arduous duties required

of a soldier. Many skirmishes and

actions of more or less importance were

participated in. February 13th, 1864, the

regiment took a steamer for Jacksonville,

Fla, and spent considerable time in that

section and at various points on the St.

Johns river. In June the regiment was

ordered to the vicinity of Charleston, and

took part in several of the engagements

which occurred in that neighborhood, always

sustaining and adding to the reputation they

were acquiring for bravery and good

soldierly conduct. The regiment passed

its entire time of active service in the

department to which it was first sent, and

returned to Boston, Mass., where it was

mustered out, amid great rejoicing, on the

23rd of September, 1865. The battles

in which the 54th Regiment were engaged were

some of the most sanguinary of the war.

The last fight of the regiment, which, like

the battle of New Orleans, took place after

peace was declared, is thus described by the

Drummer Boy of Company C, Henry A. Monroe,

of New Bedford, Mass.:

BOYKIN'S MILL.

"One

wailing bugle note, -

Then at the break of day,

With Martial step and gay,

The army takes its way

From Camden town.There lay along

the path,

Defending native land;

A daring, desperate band