|

Important services were rendered by the

Phalanx in the West. The operations in

Missouri, Tennessee and Kentucky, afforded

an excellent opportunity to the commanders

of the Union forces to raise negro troops in

such portions of the territory as they held;

but in consequence of the bitterness against

such action by the semi-Unionists and

Copperheads in the Department of the Ohio

and Cumberland, it was not until the fall of

1863 that the organizing of such troops in

these Departments fairly began. The

Mississippi was well-nigh guarded by Phalanx

regiments enlisted along that river,

numbering about fifty thousand men.

They garrisoned the fortifications, and

occupied the captured towns. Later on,

however, when the confederate General

Bragg began preparations for the

recovery of the Tennessee Valley,

organization of the Phalanx

commenced in earnest, and proceeded with a

rapidity that astounded even those who were

favorable to the policy. St. Louis

became a depot and Benton Barracks a

recruiting station, from whence, in the fall

of 1863, went many a regiment of brave black

men, whose chivalrous deeds will ever live

in the annals of the nation. It was

not long after this time that the noble Army

of the Cumberland began to receive a portion

of the black troops, whose shouts rang

through the mountain fastnesses. The

record made by the 60th Regiment is the

boast of the State of Iowa, to which it was

accredited: but of those which went to the

assistance of General Thomas'

army none won greater distinction and honor

than the gallant brigade com-

[Pg. 287]

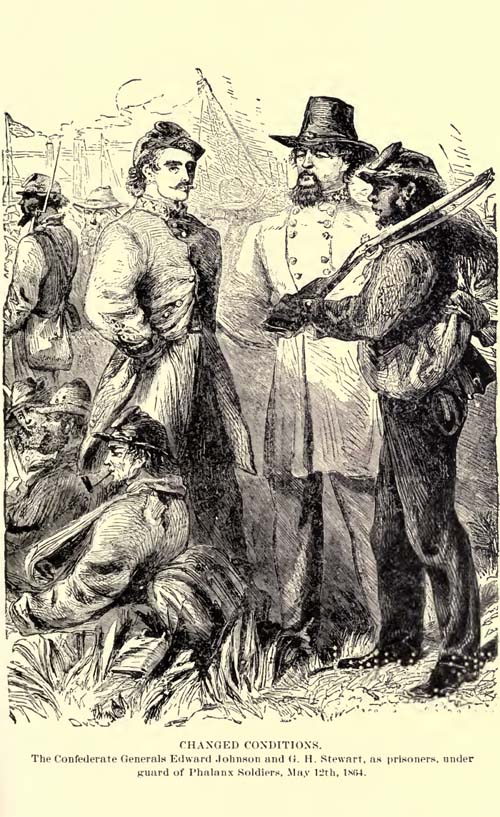

CHANGED CONDITIONS

The Confederate Generals Edward Johnson and

G. H. Stewart, as prisoners, under

guard of Phalanx Soldiers, May 12th, 1864

[Pg. 288] - BLANK

[Pg. 289]

manded by Colonel T. J. Morgan,

afterwards raised to Brigadier-General.

The gallant 14th Infantry was one of

its regiments, the field officers of which

were Colonel, Thomas J. Morgan, who

had been promoted through various grades,

from a 1st Lieutenancy in the 70th Indiana

Volunteer Infantry; Lieutenant-Colonel,

H. C. Corbin, who had risen from a 1st

Lieutenancy of the 79th O. V. 1., and

Major N. J. Vail, who had served as an

enlisted man in the 19th Illinois

Volunteers. All the officers passed a

rigid examination before the board of

examiners appointed by the War Department

for that purpose.

General Moreran. by request furnishes the

following highly interesting and historical

statement of his services with the Phalanx

Brigade:

"The American Civil War of 1861-5 marks

an epoch not only in the history of the

United States, but in that of democracy, and

of civilization. Its issue has vitally

affected the course of human progress. To

the student of history it ranks along with

the conquests of Alexander; the

incursions of the Barbarians; the Crusades;

the discovery of America and the American

Revolution. It settled the question of

our National unity with all the consequences

attaching thereto. It exhibited in a

very striking manner the power of a free

people to preserve their form of government

against its most dangerous foe, Civil War.

It not only enfranchised four millions of

American slaves of African descent, but made

slavery forever impossible in the great

Republic, and gave a new impulse to the

cause of human freedom. Its influence

upon American slaves was immediate and

startlingly revolutionary, lifting them from

the condition of despised chattels, bought

and sold like sheep in the market, with no

rights which the white man was bound to

respect,—to the exalted plane of American

citizenship ; made them free men, the peers

in every civil and political right, of their

late masters. Within about a decade

after the close of the war, negroes, lately

slaves, were legislators, state officers,

members of Congress, and for a brief time

one presided over the Senate of the United

States, where only a few years before,

Toombs had boasted that he would yet

call the roll of his slaves in the shade of

Bunker Hill.

"To-day slavery finds no advocate, and the colored race

in America is making steady progress in all

the elements of civilization. The

conduct of the American slave during, and

since the war, has wrought an extraordinary

change in public sentiment, regarding the

capabilities of the race.

"The manly qualities of the negro soldiers, evinced in

camp, on the march and in battle, won for

them golden opinions, made their freedom a

necessity and their citizenship a certainty.

"Those of us who assisted in organizing, disciplining

and leading

[Pg. 290]

negro troops in battle, may,

perhaps, be pardoned for feeling a good

degree of pride in our share of the

thrilling events of the great war.

"When Sumter was fired upon, April, 1861, I was 21; a

member of the Senior Class in Franklin

College, Indiana. I enlisted in the

7th Indiana Volunteer infantry and served as

a private soldier for three months in West

Virginia, under Gen. McClellan,—'

the young Napoleon,' as he was even

then known. I participated in the battle of

Carricks Ford, where Gen. Garnett

was killed and his army defeated. In August

1862, I re-enlisted as a First Lieutenant in

the 70th Indiana, (Col. Benjamin Harrison)

and saw service in Kentucky and Tennessee.

"In January 1863, Abraham Lincoln issued

the Proclamation of Emancipation, and

incorporated in it the policy of arming the

negro for special service in the Union army.

Thus the question was fairly up, and I

entered into its discussion with the deepest

interest, as I saw that upon, its settlement

hung great issues.

"On the one hand the opponents of the policy maintained

that to make soldiers of the negroes would

be to put them on the same level with white

soldiers, and so be an insult to every man

who wore the blue. It was contended,

too, that the negro was not fit for a

soldier because he belonged to a degraded,

inferior race, wanting in soldierly

qualities; that

his long bondage had crushed out whatever of

manliness he might naturally possess; that

he was too grossly ignorant to perform,

intelligently, the duties of the soldier;

that his provocation had been so great as a

slave, that when once armed, and conscious

of his power as a soldier, he would abuse it

by acts of revenge and wanton cruelty.

"It was urged, on the other hand, that in its fearful

struggle for existence, the Republic needed

the help of the able-bodied negroes; that

with their natural instincts of

self-preservation, desire for liberty, habit

of obedience, power of imitation, love of

pomp and parade, acquaintance with the

southern country and adaptation to its

climate, they had elements which peculiarly

fitted them for soldiers. It was

further urged that the negro had more at

stake than the white man, and that he should

have a chance to strike a blow for himself.

It was particularly insisted upon that he

needed just the opportunity which army

service afforded to develop and exhibit

whatever of manliness he possessed. As

the war progressed, and each great

battle-field was piled with heaps of the

killed and wounded of our best citizens, men

looked at each other

seriously, and asked if a black man would

not stop a bullet as well as a white man?

Miles O'Reilly at length voiced a

popular sentiment when he said,

" 'The right, to be killed I'll divide

with the nayger,

And give him the largest half.'

"With the strong conviction that the negro

was a man worthy of freedom, and possessed

of all the essential qualities of a good

soldier, I early advocated the organization

of colored regiments,—not for fatigue or

garrison duly, but for field service.

"In October, 1863, having applied for a position as an

officer in the

[Pg. 291]

colored service, I was

ordered before the Board of Examiners at

Nashville, Tennessee, where I spent five

rather anxious hours. When I entered

the army I knew absolutely nothing of the

details of army life; had never even drilled

with a fire company. During the first

three months I gathered little except a

somewhat rough miscellaneous experience.

As a

lieutenant and staff officer I learned

something, but as I had never had at any

time systematic instruction from any one, I

appeared before the Board with little else

than vigorous health, a college education, a

little experience as a soldier, a good

reputation as an officer, a fair amount of

common sense and a good supply of zeal.

The Board averaged me, and

recommended me for a Major.

"A few days after the examination, I received an order

to report to Major George L. Stearns,

who had charge of the organization of

colored troops in that Department. He

assigned me to duty temporarily in a camp in

Nashville. Major Stearns was a

merchant in Boston, who had been for years

an ardent abolitionist, and who, among other

good deeds,

had befriended John Brown.

He was a large-hearted, broad-minded genial

gentleman. When the policy of

organizing colored troops was adopted, he

offered his services to the Government,

received an appointment as Assistant

Adjutant General, and was ordered to

Nashville to organize colored regiments.

He acted directly under the Secretary of

War, and independently of the Department

Commander. To his zeal, good judgment

and efficient labor, was due, very largely,

the success of the work in the West.

"November 1st, 1863, by order of Major

Stearns, I went to Gallatin, Tennessee,

to organize the 14th United States Colored

Infantry. General E. A. Paine

was then in command of the post at Gallatin,

having under him a small detachment of white

troops. There were at that time

several hundred negro men in camp, in charge

of, I think, a lieutenant. They were a

motley crowd,—old, young, middle aged.

Some wore the United States uniform, but

most of them had on the clothes in which

they had left the plantations, or had worn

during periods of hard service as laborers

in the army. Gallatin at that time was

threatened with an attack by the guerilla

bands then prowling over that part of the

State. General Paine had

issued a hundred old muskets and rifles to

the negroes in camp. They had not

passed a medical examination, had no company

organization and had had no drill.

Almost immediately upon my arrival, as an

attack was imminent, I was ordered to

distribute another hundred muskets, and to

'prepare every available man for fight.'

I did the best I could under the

circumstances, but am free to say that I

regard it as a fortunate circumstance that

we had no fighting to do at that time.

But the men raw, and, untutored as they

were, did guard and picket duty, went

foraging, guarded wagon trains, scouted

after

guerillas, and so learned to soldier—by

soldiering.

" As soon and as fast as practicable, I set about

organizing the regiment. I was a

complete novice in that kind of work, and

all the young officers who reported to me

for duty, had been promoted from the ranks

[Pg. 292]

and were without experience,

except as soldiers. The colored men

knew nothing of the duties of a soldier,

except a little they had picked up as

camp-followers.

" Fortunately there was one man, Mr. A. H. Dunlap,

who had had some clerical experience with

Col. Birney, in Baltimore, in

organizing the 3rd U. S. Colored Infantry.

He was an intelligent, methodical gentle

man, and rendered me invaluable service.

I had no Quartermaster; no Surgeon; no

Adjutant. We had no tents, and the men

were sheltered in

an old filthy tobacco warehouse, where they

fiddled, danced, sang, swore or prayed,

according to their mood.

"How to meet the daily demands made upon us for

military duty, and at the same time to evoke

order out of this chaos, was no easy

problem. The first thing to be done

was to examine the men. A room was

prepared, and I and my clerk took our

stations at a table. One by one the

recruits came before us a la Eden, sans

the fig leaves, and were subjected to a

careful medical examination, those who were

in any way physically disqualified being

rejected. Many bore the wounds and

bruises of the slave-driver's lash, and many

were unfit for duty by reason of some form

of disease to which human flesh is heir. In

the course of a few weeks, however, we had a

thousand able-bodied, stalwart men.

"I was quite as solicitous about their mental condition

as about their physical status, so I plied

them with questions as to their history,

their experience with the army, their

motives for becoming soldiers, their ideas

of army life, their hopes for the future,

&c, &c. I found that a considerable

number of them had been teamsters, cooks,

officers' servants, &c, and had thus seen a

good deal of hard service in both armies, in

camp, on the march and in battle, and so

knew pretty well what

to expect. In this respect they had the

advantage of most raw recruits from the

North, who were wholly ' unusued to

wars' alarms.' Some of them had very

noble ideas of manliness. I remember

picturing to one bright-eyed fellow some of

the hardships of camp life and campaigning,

and receiving from him the cheerful reply,

'I know all about that.' I then said,

'you may be killed in battle.' He

instantly answered, 'many a better man than

me has been killed in this war.' When

I told another one who wanted to 'fight for

freedom,' that he might lose his life, he

replied, ' but my people will be free."

"The result of this careful examination convinced me

that these men, though black in skin, had

men's hearts, and only needed right handling

to develope into magnificent

soldiers. Among them were the same varieties

of physique, temperament, mental and moral

endowments and experiences, ns would be

found among the same number of white men.

Some of them were finely formed and

powerful; some were almost white; a large

number had in their veins white blood of the

F. F. V. quality; some were men of

intelligence, and many of them deeply

religious.

"Acting upon my clerk's suggestion, I assigned them to

companies according to their height, putting

men of nearly the same height together.

When the regiment was full, the four center

companies were all.

[Pg. 293]

composed of tall men, the flanking companies

of men of medium height, while the little

men were sandwiched between. The

effect was excellent in every way, and made

the regiment quite unique. It was not

uncommon to have strangers who saw it parade

for the first time, declare that the men

were all of one size.

"In six weeks three companies were filled, uniformed,

armed, and had been taught many soldierly

ways. They had been drilled in the

facings, in the manual of arms, and in some

company movements.

"November 20th, Gen. G. H. Thomas commanding the

Department of the Cumberland, ordered six

companies to Bridgeport, Alabama, under

command of Major H. C. Corbin.

I was left at Gallatin to complete the

organization of the other four companies.

When the six companies were full, I was

mustered in as Lieutenant-Colonel. The

complete organization of the regiment

occupied about two mouths, being finished by

Jan. 1st, 1864. The field, staff and

company officers were all white men.

All the non-commissioned officers, Hospital

Steward, Quartermaster, Sergeant,

Sergeant-Major, Orderlies, Sergeants and

Corporals were colored. They proved

very efficient, and had the war continued

two years longer, many of them would have

been competent as commissioned officers.

"When General Paine left Gallatin, I was

senior officer and had command of the post

and garrison, which included a few white

soldiers besides my own troops.

Colored soldiers acted as pickets, and no

citizen was allowed to pass our lines either

into the village or out, without a proper

permit. Those presenting themselves

without a pass were sent to headquarters

under guard. Thus many proud Southern

slave-holders found themselves marched

through the street, guarded by those who

three months before had been slaves.

The negroes often laughed over these changed

relations as they sat around their camp

fires, or chatted together while off duty,

but it was very rare that any Southerner had

reason to complain of any unkind or uncivil

treatment from a colored soldier.

" About the first of January occurred a few days of

extreme cold weather, which tried the men

sorely. One morning after one of the

most severe nights, the officers coming in

from picket, marched the men to

headquarters, and called attention to their

condition: their feet were frosted and their

hands frozen. In some instances the

skin on their fingers had broken from the

effects of the cold, and it was sad to see

their sufferings. Some of them never

recovered from the effects of that night,

yet they bore it patiently and

uncomplainingly.

"An incident occurred while I was still an officer in a

white regiment, that illustrates the curious

transition through which the negroes were

passing. I had charge of a company

detailed to guard a wagon train out

foraging. Early one morning, just as

we were about to resume our march, a

Kentucky lieutenant rode up to me, saluted,

and said he had some runaway negroes whom he

had arrested to send back to their masters,

but as he was ordered away, he would turn

them over to me. (At

[Pg. 294]

that time a reward could be claimed for

returning fugitive slaves. I took

charge of them, and assuming a stern look

and manner, enquired, 'Where are you going?'

'Going to the Yankee army.' 'What for?' '

We wants to be free, sir.' 'All right,

you are free, go where you wish.' The

satisfaction that came to me from their

heartfelt ' thank'ee, thank'ee sir,' gave me

some faint insight into the sublime joy that

the great emancipator must have felt when he

penned the immortal proclamation that set

free four millions of human beings.

"These men afterward enlisted in my regiment, and did

good service. One day, as we were on

the march, they through their lieutenant

reminded me of the circumstance, which they

seemed to remember with lively gratitude.

"The six companies at Bridgeport were kept very busily

at work, and had but little opportunity for

drill. Notwithstanding these

difficulties, however, considerable progress

was made in both drill and discipline.

I made earnest efforts to get the regiment

united and relieved from so much labor, in

order that they might be prepared for

efficient field service as soldiers.

"In January I had a personal interview with General

Thomas, and secured an order uniting

the regiment at Chattanooga. We

entered camp there under the shadow of

Lookout Mountain, and in full view of

Mission Ridge, in February, 1864.

During the same month Adjutant General

Lorenzo Thomas, from Washington, then on

a tour of inspection, visited my regiment,

and authorized me to substitute the eagle

for the silver leaf.

"Chattanooga was at that time the headquarters of the

Army of the Cumberland. Gen Thomas

and staff, and a considerable part of the

army were there. Our camp was laid out

with great regularity; our quarters were

substantial, comfortable and well kept.

The regiment numbered a thousand men, with a

full compliment of field, staff, line and

non-commissioned officers. We had a

good drum corps, and a band pro- vided with

a set of expensive silver instruments.

We were also fully equipped; the men were

armed with rifled muskets, and well clothed.

They were well drilled in the manual of

arms, and took great pride in appearing on

parade with arms burnished, belts polished,

shoes blacked, clothes brushed, in full

regulation uniform, including white gloves.

On every pleasant day our parades were

witnessed by officers, soldiers and citizens

from the North, and it was not uncommon to

have two thousand spectators. Some

came to make sport, some from curiosity,

some because it was the fashion, and others

from a genuine desire to see for themselves

what sort of looking soldiers negroes would

make.

"At the time that the work of organizing colored troops

began in the West, there was a great deal of

bitter prejudice against the movement, and

white troops threatened to desert, if the

plan should be really carried out.

Those who entered the service were

stigmatized as ' nigger officers,' and negro

soldiers were hooted at and mal-treated by

white ones.

[Pg. 295]

"Apropos of the prejudice against so called nigger

officers, I may mention the following

incident: While an officer in the 70th

Indiana, I had met, and formed a passing

acquaintance with Lieut.-Colonel, of the

Ohio Regiment. On New Years Day, 1864,

1 chanced to meet him at a social gathering

at General Ward's headquarters

in Nashville. I spoke to him as usual,

at the same time offering my hand, which

apparently he did not see. Receiving

only a cool bow from him, I at once turned

away. As I did so he remarked to those

standing near him that he ' did not

recognize these nigger officers.' In

some way, I do not know how, a report of the

occurrence came to the ears of Lorenzo

Thomas, the Adjutant-General of the

Army, then in Nashville, who investigated

the case, and promptly dismissed Colonel

from the United States service.

"Very few West Point officers had any faith in the

success of the enterprise, and most Northern

people perhaps, regarded it as at best a

dubious experiment. A college

classmate of mine, a young man of

intelligence and earnestly loyal, although a

Kentuckian, and a slave-holder, plead with

me to abandon my plan of entering this

service, saying, 'I shudder to think of the

remorse you may suffer, from deeds done by

barbarians under your command.'

"General George H. Thomas, though a Southerner,

and a West Point graduate, was a singularly

fair-minded, candid man. He

asked me one day soon after my regiment was

organized, if I thought my men would fight.

I replied that they would. He said he

thought 'they might behind breastworks.'

I said they would fight in the open field.

He thought not. 'Give me a chance

General,' I replied, 'and I will prove it.'

"Our evening parades converted thousands to a belief in

colored troops. It was almost a daily

experience to hear the remark from visitors,

'Men who can handle their arms as these do,

will fight.' General Thomas

paid the regiment the compliment of saying

that he 'never saw a regiment go through the

manual as well as this one.' We

remained in 'Camp Whipple' from February,

1864, till August, 1865, a period of

eighteen months, and during a large part of

that time the regiment was an object lesson

to the army, and helped to revolutionize

public opinion on the subject of colored

soldiers.

"My Lieutenant-Colonel and I rode over one evening to

call on General Joe Hooker,

commanding the 20th Army Corps. He

occupied a small log hut in the Wauhatchie

Valley, near Lookout Mountain and not far

from the Tennessee river. He received

us with great courtesy, and when he learned

that we were officers in a colored regiment,

congratulated us on our good fortune, saying

that he 'believed they would make the best

troops in the world.' He predicted

that after the rebellion was subdued, it

would be necessary for the United States to

send an army into Mexico. This army

would be composed largely of colored men,

and those of us now holding high command,

would have a chance to win great renown.

He lamented that he had made a great mistake

in not accepting a military command, and

going to Nicaragua with Gen-

[Pg. 296]

eral Walker. 'Why,' said he,

'young gentlemen, I might have founded an

empire.'

' " While at Chattanooga, I organized two other

regiments, the 42nd and the 44th United

States Colored Infantry. In addition

to the ordinary instruction in the duties

required of the soldier, we established in

every company a regular school, teaching men

to read and write, and taking great pains to

cultivate in them self-respect and all manly

qualities. Our success in this respect

was ample compensation for our labor.

The men who went on picket or guard duty,

took their books as quite as indispensable

as their coffee pots.

"It must not be supposed that we had only plain

sailing. Soon after reaching

Chattanooga, heavy details began to be made

upon us for men to work upon the

fortifications then in process of

construction around the town. This

almost incessant labor, interfered sadly

with our drill, and at one time all drill

was suspended, by orders from headquarters.

There seemed little prospect of our being

ordered to the field, and as time wore on

and arrangements began in earnest for the

new campaign against Atlanta, we grew

impatient for work, and anxious for

opportunity for drill and preparations for

field service.

" I used every means to bring about a change, for I

believed that the ultimate status of the

negro was to be determined by his conduct on

the battle-field. No one doubted that

he would work, while many did doubt that he

had courage to stand up and fight like a

man. If he could take his place side

by side with the white soldier; endure the

same hardships on the campaign, face the

same enemy, storm the same works, resist the

same assaults, evince the same soldierly

qualities, he would compel that respect

which the world has always accorded to

heroism, and win for himself the same

laurels which brave soldiers have always

won.

" Personally, I shrink from danger, and most decidedly

prefer a safe corner at my own fireside, to

an exposed place in the face of an enemy on

the battle-field, but so strongly was I

impressed with the importance of giving

colored troops a fair field and full

opportunity to show of what mettle they were

made, that I lost no chance of insisting

upon our right to be ordered into the field.

At one time I was threatened with dismissal

from the service for my persistency, but

that did not deter me, for though I had no

yearning for martyrdom, I was determined if

possible to put my regiment into battle, at

whatever cost to myself. As I look

back upon the matter after twenty-one years,

I see no reason to regret my action, unless

it be that I was not even more persistent in

claiming for these men the rights of

soldiers.

" I was grievously disappointed when the first of May,

1864, came, and the army was to start south,

leaving us behind to hold the forts we had

helped to build.

"I asked General Thomas to allow mp, at

least, to go along. He readily

consented, and directed me to report to

General O. O. Howard, commanding the 4th

Army Corps, as Volunteer Aide. I did

so, and remained with him thirty days,

participating in the battles of Buzzard's

[Pg. 297]

Roost, Resaca, Adairsville and Dallas.

At the end of that time, having gained

invaluable experience, and feeling that my

place was with my regiment, I returned to

Chattanooga, determined to again make every

possible effort to get it into active

service.

"A few days after I had taken my place on General

Howard's staff, an incident occurred

showing how narrowly one may escape death.

General Stanley and a staff

officer and General Howard and

myself were making a little reconnoissance

at Buzzards Roost. We stopped to

observe the movements of the enemy,

Stanley standing on the right, Howard

next on his left, and I next. The

fourth officer, Captain Hint,

stood immediately in the rear of General

Howard. A sharpshooter paid us

a compliment in the shape of a rifle ball,

which struck the ground in front of

General Howard, ricocheted,

passed through the skirt of his coat,

through Captain Flint's cap,

and buried itself in a tree behind.

"At Adairsville a group of about a dozen mounted

officers were in an open field, when the

enemy exploded a shell just in front and

over us, wounding two officers and five

horses. A piece of the shell passed

through the right fore leg of my horse, a

kind, docile, fearless animal, that I was

greatly attached to. I lost a friend

and faithful servant.

"On asking leave to return to my command, I was

delighted to receive from General

Howard the following note:

" ' HEADQUARTERS 4TH ARMY CORPS.

" 'ON ACKWORTH AND DALLAS ROAD, 8 MILES FROM DALLAS,

GA., May 31st 1864.

" 'COLONEL: - This is to express my thanks for your

services upon my staff during the past

month, since starting upon this campaign.

You have given me always full satisfaction,

and more, by your assiduous devotion to

duty.

" 'You have been active and untiring on the march, and

fearless in battle. Believe me,

Your friend,

O. O. HOWARD

" 'Major-General Commanding 4th Army Corps.

" 'To Col. T. J. Morgan,

Commanding 14th U. S. C. I.'

"General

James B. Steadman, who won such

imperishable renown at Chickamauga, was then

in command of the District of Etowah, with

headquarters at Chattanooga. I laid my

case before him; he listened with interest

to my plea, and assured me that if there was

any fighting to be done in his district, we

should have a hand in it.

"DALTON, GA. August l0th, 1864, we had our first fight,

at Dalton, Georgia. General

Wheeler, with a considerable force of

confederate cavalry, attacked Dalton, which

was occupied by a small detachment of Union

troops belonging to the 2nd Missouri, under

command of Colonel Laibold.

General Steadman went to

Laibold's aid, and forming line of

battle, attacked and routed the Southern

force. My regiment formed on the left

of the 51st Indiana Infantry, under command

of Col. A. D. Streight. The

fight was short, and not at all severe.

The regiment was all exposed to fire.

One private was killed, one lost a leg, and

one was wounded in the right hand.

Company B, on the skirmish line killed five

of the enemy, and wounded others. To

us it was a great battle, and a glorious

victory. The regiment had been

recognized as soldiers; it had taken its

place side by side with a white regiment; it

had been under fire. The men had

behaved gallantly. A colored soldier

had died for liberty. Others had shed

their blood in the great cause. Two or

three

[Pg. 298]

incidents will indicate the significance of

the day. Just before going into the

fight, Lieutenant Keinborts

said to his men: 'Boys, some of you may be

killed, but remember you are fighting for

liberty.' Henry Prince

replied, 'I am ready to die for liberty.'

In fifteen minutes he lay dead, a rifle ball

through his heart, a willing martyr.

"During the engagement General Steadman

asked his Aide, Captain Davis,

to look especially after the 14th colored.

Captain Davis rode up

just as I was quietly rectifying my line,

which in a charge had been disarranged.

Putting spurs to his horse, he dashed back

to the General and reassured him by

reporting that 'the regiment was holding

dress parade over there under fire.'

After the fight, as we marched into town,

through a pouring rain, a white regiment

standing at rest, swung their hats and gave

three rousing cheers for the 14th Colored.

Col. Streight's command was so

pleased with the gallantry of our men that

many of its members on being asked, 'What

regiment?' frequently replied, '5lst

Colored.'

" During the month of August we had some very hard

marching, in a vain effort to have another

brush with Wheeler's cavalry.

"The corn in East Tennessee was in good plight for

roasting, and our men showed great facility

in cooking, and marvelous capacity in

devouring it. Ten large ears were not

too much for many of them. On resuming

our march one day, after the noon halt, one

of the soldiers said he was unable to walk,

and asked permission to ride in an

ambulance. His comrades declared that,

having already eaten twelve ears of corn,

and finding himself unable to finish the

thirteenth, he concluded that he must be

sick, and unfit for duty.

" PULASKI, TENN. September 27th, 1864, I reported to

Major-General Rousseau,

commanding a force of cavalry at Pulaski,

Tenn. As we approached the town by

rail from Nashville, we heard artillery,

then musketry, and as we left the cars we

saw the smoke of guns. Forest,

with a large body of cavalry, had been

steadily driving Rousseau before him

all day, and was destroying the railroad.

Finding the General, I said: 'I am ordered

to report to you, sir.' 'What have

you?' 'Two regiments of colored

troops.' Rousseau was a Kentuckian,

and had not much faith in negro soldiers.

By his direction I threw out a strong line

of skirmishers, and posted the regiments on

a ridge, in good supporting distance.

Rousseau's men retired behind my

line, and Forest's men pressed

forward until they met our fire, and

recognizing the sound of the minie ball,

stopped to reflect.

"The massacre of colored troops at Fort Pillow was well

known to us, and had been fully discussed by

our men. It was rumored, and

thoroughly credited by them, that General

Forest had offered a thousand dollars

for the head of any commander of a 'nigger

regiment.' Here, then, was just such

an opportunity as those spoiling for a fight

might desire. Negro troops stood face

to face with Forest's veteran cavalry.

The fire was growing hotter, and balls were

uncomfortably thick. At length, the

enemy in strong force, with banners flying,

bore down toward

[Pg. 299]

us in full sight, apparently bent on

mischief. Pointing to the advancing

column, I said, as I passed along the line,

'Boys, it looks very much like fight; keep

cool, do your duty.' They seemed full

of glee, and replied with great enthusiasm:

'Colonel, dey can't whip us, dey nebber get

de ole 14th out of heah, nebber.' 'Nebber,

drives us away widout a mighty lot of dead

men,' &c., &c.

"When Forest learned that Rousseau was

re-enforced by infantry, he did not stop to

ask the color of the skin, but after testing

our line, and finding it unyielding, turned

to the east, and struck over toward

Murfreesboro.

"An incident occurred here, illustrating the humor of

the colored soldier. A spent ball

struck one of the men on the side of the

head, passed under the scalp, and making

nearly a circuit of the skull, came out on

the other side. His comrades merrily

declared that when the ball struck him, it

sang out 'too thick' and passed on.

"As I was walking with my adjutant down toward the

picket line, a ball struck the ground

immediately in front of us, about four feet

away, but it was so far spent as to the

harmless. We picked it up and carried

it along.

"Our casualties consisted of a few men slightly

wounded. We had not had a battle, but

it wa for us a victory, for our troops had

stood face to face with a triumphant force

of Southern cavalry, and stopped their

progress. They saw that they had done

what Rousseau's veterans could not

do. Having traveled 462 miles, we

returned to Chattanooga, feeling that we had

gained valuable experience, and we eagerly

awaited the next opportunity for battle,

which was not long delayed.

"DECATUR, ALA. - Our next active service was at

Decatur, Alabama. Hood, with

his veteran army that had fought Sherman

so gallantly from Chattanooga to Atlanta,

finding that his great antagonest had

started southward and seaward, struck out

boldly himself for Nashville. Oct.

27th I reported to General R. S. Granger,

commanding at Decatur. His little

force was closely besieged by Hood's

army, whose right rested on the Tennessee

river below the town, and whose left

extended far beyond our lines, on the other

side of the town. Two companies of my

regiment were stationed on the opposite side

of the river from Hood's right, and

kept up an annoying musketry fire.

Lieutenant Gillett, of Company G, was

mortally wounded by a cannon ball, and some

of the enlisted men were hurt. One private

soldier in Company B, who had taken position

in a tree as sharpshooter, had his right arm

broken by a ball. Captain Romeyn

said to him, 'You would better come down

from there, go to the rear, and find the

surgeon.' 'Oh no, Captain!' he

replied, 'I can fire with my left arm,' and

so he did.

"Another soldier of Company B, was walking along the

road, when hearing an approaching cannon

ball, he dropped flat upon the ground, and

was almost instantly well nigh covered with

the dirt plowed up by it, as it struck the

ground near by. Captain

Romeyn, who witnessed the incident, and

who was greatly amused by the fellow's

trepidation,

[Pg. 300]

asked him if he was frightened? His

reply was, 'Fore God, Captain, I thought I

was a dead man, sure!'

" Friday, Oct. 28th, 1864, at twelve o'clock, at the

head of 355 men, in obedience to orders from

General Granger, I charged and

took a battery, with a loss of sixty

officers and men killed and wounded.

After capturing the battery, and spiking the

guns, which we were unable to remove, we

retired to our former place in the line of

defense. The conduct of the men on

this occasion was most admirable, and drew

forth high praise from Generals

Granger and Thomas.

"Hood, having decided to push on to Nashville

without assaulting Decatur, withdrew.

As soon as I missed his troops from my

front, I notified the General commanding,

and was ordered to pursue, with the view of

finding where he was. About ten

o'clock the next morning, my skirmishers

came up with his rear guard, which opened

upon us a brisk infantry fire.

Lieutenant Woodworth, standing at

my side, fell dead, pierced through the

face. General Granger

ordered me to retire inside of the works,

and the regiment, although exposed to a

sharp fire, came off in splendid order.

As we marched inside the works, the white

soldiers, who had watched the manoeuvre,

gave us three rousing cheers. I have

heard the Pope's famous choir at St. Peters,

and the great organ at Freibourg, but the

music was not so sweet as the hearty

plaudits of our brave comrades.

"As indicating the change in public sentiment relative

to colored soldiers, it may be mentioned

that the Lieutenant-Colonel commanding the

68th Indiana Volunteer Infantry, requested

me as a personal favor to ask for the

assignment of his regiment to my command,

giving as a reason that his men would rather

fight along side of the 14th Colored than

with any white regiment. He was

ordered to report to me.

"After Hood had gone, and after our journey of 244

miles, we returned to Chattanooga, but not

to remain.

"NASHVILLE, TENN. Nov. 29, 1864, in command of the

14th, 16th and 44th Regiments U. S. C. I., I

embarked on a railroad train at Chattanooga

for Nashville. On December 1st, with

the 1 6th and most of the 14th, I reached my

destination, and was assigned to a place on

the extreme left of General Thomas'

army then concentrating for the defence of

Nashville against Hood's threatened

attack.

"The train that contained the 44th colored regiment,

and two companies of the 14th, under command

of Colonel Johnson, was

delayed near Murfreesboro until Dec. 2nd,

when it started for Nashville. But

when crossing a bridge not far from the

city, its progress was suddenly checked by a

cross-fire of cannon belonging to Forest's

command. I had become very anxious

over the delay in the arrival of these

troops, and when I heard the roar of cannon

thought it must be aimed at them. I

never shall forget the intensity of my

suffering, as hour after hour passed by

bringing me no tidings. Were they all

captured? Had they been massacred?

Who could answer? No one. What was to

be done? Nothing. I could only

wait and suffer.

[Pg. 301]

"The next day Colonel Johnson reached Nashville,

reporting that when stopped, he and his men

were forced, under heavy fire, to abandon

the train, clamber down from the bridge, and

run to a blockhouse near by, which had been

erected for the defence of the bridge, and

was still in possession of the Union

soldiers. After maintaining a stubborn

fight until far into the night, he withdrew

his troops, and making a detour to the east

came into our lines, having lost in killed,

wounded and missing, two officers and eighty

men of the 44th, and twenty-five men of the

14th.

"Just as Captain C. W. Baker, the senior officer

of the 14th, was leaving the car, a piece of

shell carried off the top of his cap, thus

adding immensely to its value as a souvenir.

Some of the soldiers who escaped lost

everything except the clothes they had on,

including knapsacks, blankets and arms.

In some cases they lay in the water hiding

for hours, until they could escape their

pursuers.

"Soon after taking our position in line at Nashville,

we were closely beseiged by Hood's

army; and thus we lay facing each other for

two weeks. Hood had suffered so

terribly by his defeat under Schofield,

at Franklin, that he was in no mood to

assault us in our works, and Thomas

needed more time to concentrate and

reorganize his army, before he could safely

take the offensive. That fortnight

interval was memorable indeed.

Hood's army was desperate. It had

been thwarted by Sherman, and thus

far baffled by Thomas, and Hood

felt that he must strike a bold blow to

compensate for the dreadful loss of prestige

occasioned by Sherman's march to the

sea. His men were scantily clothed and

poorly fed; if he could gain Nashville, our

great depot of supplies, he could furnish

his troops with abundance of food, clothing

and war material; encourage the confederacy,

terrify the people of the North, regain a

vast territory taken from the South at such

great cost to us, recruit his army from

Kentucky, and perhaps invade the North.

"Thomas well knew the gravity of the situation,

and was unwilling to hazard all by a

premature battle. I think that neither

he nor any of his army ever doubted the

issue of the battle when it should come,

whichever force should take the initiative.

"The authorities at Washington grew restive, and the

people at the North nervous. Thomas

was ordered to fight, Logan was

dispatched to relieve him if he did not, and

Grant himself started West to take

command. Thomas was too good a

soldier to be forced to offer battle, until

he was sure of victory. He knew that

time was his best ally, every day adding to

his strength and weakening his enemy.

In the meantime the weather became intensely

cold, and a heavy sleet covered the ground,

rendering it almost impossible for either

army to move at all. For a few days

our sufferings were quite severe. We

had only shelter tents for the men, with

very little fuel, and many of those who had

lost their blankets keenly felt their need.

"On December 5th, before the storm, by order of

General Steadman, I made a little

reconnaissance, capturing, with slight loss,

Lieutenant Gardner and six

men, from the 5th Mississippi Regiment.

December 7th

[Pg. 302]

we made another, in which Colonel

Johnson and three or four men were

wounded. On one of these occasions,

while my men were advancing in face of a

sharp fire, a rabbit started up in front of

them. With shouts of laughter, several

of them gave chase, showing that even battle

could not obliterate the negro's love of

sport.

"But the great day drew near. The weather grew

warmer; the ice gave way. Thomas

was ready, and calling together his chiefs,

laid before them his plan of battle.

"About nine o'clock at night December 14th, 1864, I was

summoned to General Steadman's

headquarters. He told me what the plan

of battle was, and said he wished me to open

the fight by making a vigorous assault upon

Hood's right flank. This, he

explained, was to be a feint, intended to

betray Hood into the belief that it

was the real attack, and to lead him to

support his right by weakening his left,

where Thomas in- tended assaulting

him in very deed. The General gave me

the 14th United States Colored Infantry,

under Colonel H. C. Corbin; the 17th

U. S. C. I., under the gallant Colonel W.

R. Shafter; a detachment of the 18th U.

S. C. I., under Major L. D. Joy; the

44th U. S. C. I., under Colonel L.

Johnson; a provisional brigade of white

troops under Colonel C. H. Grosvenor,

and a section of Artillery, under Captain

Osburn, of the 20th Indiana Battery.

" The largest force I had ever handled was two

regiments, and as I rather wanted to open

the battle in proper style, I asked

General Steadman what suggestion

he had to make. He replied: 'Colonel,

tomorrow morning at daylight I want you to

open the battle.' 'All right,

General, do you not think it would be a good

plan for me to', and I outlined a little

plan of attack. With a twinkle in his

kindly eye, he replied: 'Tomorrow morning,

Colonel, just as soon as you can see how to

put your troops in motion, I wish you to

begin the fight.' 'All right, General,

good night.' With these explicit

instructions, I left his headquarters,

returned to camp, and gave the requisite

orders for the soldiers to have an early

breakfast, and be ready for serious work at

daybreak. Then taking Adjutant

Clelland I reconnoitered the enemy's

position, tracing the line of his camp

fires, and decided on my plan of assault.

"The morning dawned with a dense fog, which held us in

check for some time after we were ready to

march. During our stay in Nashville, I

was the guest of Major W. B. Lewis,

through whose yard ran our line. He

had been a warm personal friend of Andrew

Jackson, occupying a place in the

Treasury Department during his

administration. He gave me the room

formerly occupied by the hero of New

Orleans, and entertained me with many

anecdotes of him. I remember in

particular one which I especially

appreciated, because of the scarcity of fuel

in our own camp. At one time

General Jackson ordered certain

troops to rendezvous for a few days at

Nashville. Major Lewis,

acting as Quartermaster, laid in a supply of

several hundred cords of wood, which he

supposed would be ample to last during their

entire stay in the city. The troops

arrived on a 'raw and gusty day,' and being

accustomed to comfortable

[Pg. 303]

fires at home, they burned up every stick

the first night, to the quartermaster's

great consternation.

"To return: On the morning of December 15th, Major

Lewis said he would have a servant

bring me my breakfast, which was not ready,

however, when I started. The boy, with

an eye to safety, followed me afar off, so

far that he only reached me, I think, about

two o'clock in the afternoon. But I

really believe the delay, improved the

flavor of the breakfast.

" As soon as the fog lifted, the battle began in good

earnest. Hood mistook my

assault for an attack in force upon his

right flank, and weakening his left in order

to meet it, gave the coveted opportunity to

Thomas, who improved it by assailing

Hood's left flank, doubling it up,

and capturing a large number of prisoners.

"Thus the first day's fight wore away. It had

been for us a severe but glorious day.

Over three hundred of my command had fallen,

but everywhere our army was successful.

Victory perched upon our banners.

Hood had stubbornly resisted, but had

been gallantly driven back with severe loss.

The left had done its duty. General

Steadman congratulated us, saying his

only fear had been that we might fight too

hard. We had done all he desired, and

more. Colored soldiers had again

fought side by side with white troops; they

had mingled together in the charge; they had

supported each other; they had assisted each

other from the field when wounded, and they

lay side by side in death. The

survivors rejoiced together over a hard

fought field, won by a common valor.

All who witnessed their conduct, gave them

equal praise. The day that we had

longed to see had come and gone, and the sun

went down upon a record of coolness,

bravery, manliness, never to be unmade.

A new chapter in the history of liberty had

been written. It had been shown that,

marching under a flag of freedom, animated

by a love of liberty, even the slave becomes

a man and a hero.

"At one time during the day, while the battle was in

progress, I sat in an exposed place on a

piece of ground sloping down toward the

enemy, and being the only horseman on that

part of the field, soon became a target for

the balls that whistled and sang their

threatening songs as they hurried by.

At length a shot aimed at me struck my horse

in the face, just above the nostril, and

passing up under the skin emerged near the

eye, doing the horse only temporary harm,

and letting me off scot-free, much to my

satisfaction, as may be supposed.

Captain Baker, lying on the

ground near by, heard the thud of the ball

as it struck the horse, and seeing me

suddenly dismount, cried out, 'the Colonel

is shot,' and sprang to my side, glad enough

to find that the poor horse's face had been

a shield to save my life. I was sorry

that the animal could not appreciate the

gratitude I felt to it for my deliverance.

"During that night Hood withdrew his army some

two miles, and took up a new line along the

crest of some low hills, which he strongly

fortified with some improvised breast works

and abatis. Soon after our early

breakfast, we moved forward over the

intervening space. My posi-

[Pg. 304]

tion was still on the extreme left of our

line, and I was especially charged to look

well to our flank, to avoid surprise.

"The 2nd Colored Brigade, under Colonel

Thompson, of the 12th U. S. C. I., was

on my right, and participated in the first

days' charge upon Overton's Hill, which was

repulsed. I stood where the whole

movement was in full view. It was a

grand and terrible sight to see those men

climb that hill over rocks and fallen trees,

in the face of a murderous fire of cannon

and musketry, only to be driven back.

White and black mingled together in the

charge, and on the retreat.

" When the 2nd Colored Brigade retired behind my lines

to reform, one of the regimental

color-bearers stopped in the open space

between the two armies, where, although

exposed to a dangerous fire, he planted his

flag firmly in the ground, and began

deliberately and coolly to return the

enemy's fire, and, greatly to our amusement,

kept up for some little time his independent

warfare.

"When the second and final assault was made, the right

of my line took part. It was with breathless

interest I watched that noble army climb the

hill with a steady resolve which nothing but

death itself could check. When at length the

assaulting column sprang upon the

earth-works, and the enemy seeing that

further resistance was madness, gave way and

began a precipitous retreat, our hearts

swelled as only the hearts of soldiers can,

and scarcely stopping to cheer or to await

orders, we pushed forward and joined in the

pursuit, until the darkness and the rain

forced a halt.

" The battle of Nashville did not compare in numbers

engaged, in severity of fighting, or in the

losses sustained, with some other Western

battles. But in the issues at stake,

the magnificent generalship of Thomas,

the completeness of our triumph, and the

immediate and far-reaching consequences, it

was unique, and deservedly ranks along with

Gettysburg, as one of the decisive battles

of the war.

" When General Thomas rode over the

battle-field and saw the bodies of colored

men side by side with the foremost, on the

very works of the enemy, he turned to his

staff, saying: 'Gentlemen, the question is

settled; negroes will fight.' He did me the

honor to recommend me for promotion, and

told me that he intended to give me the best

brigade that he could form. This he

afterward did.

"After the great victory, we joined in the chase after

the fleeing foe. Hood's army was

whipped, demoralized, and pretty badly

scattered. A good many stragglers were

picked up. A story circulated to this

effect: Some of our boys on making a sharp

turn in the road, came upon a forlorn

Southern soldier, who had lost his arms,

thrown away his accoutrements, and was

sitting on a log by the roadside, waiting to

give himself up. He was saluted with,

'Well, Johnny, how goes it?'

'Well, Yank, I'll tell ye; I confess I'm

horribly whipped, and badly demoralized, but

blamed if I'm scattered!'

[Pg. 305]

nmn, followed by my own regiment. The

men were swinging along 'arms at will,' when

they spied General Thomas and

staff approaching. Without orders they

brought their arms to 'right shoulder

shift,' took the step, and striking up their

favorite tune of ' John Brown,'

whistled it with admirable effect while

passing the General, greatly to his

amusement.

"We had a very memorable march from Franklin to

Murfreesboro, over miserable dirt roads.

About December 19th or 20th, we were on the

march at an early hour, but the rain was

there before us, and stuck by us closer than

a brother. We were drenched through

and through, and few had a dry thread.

We waded streams of water nearly waist deep;

we pulled through mud that seemed to have no

bottom, and where many a soldier left his

shoes seeking for it. The open woods

pasture where we went into camp that night,

was surrounded with a high fence made of

cedar rails. That fence was left

standing, and was not touched —until—well, I

do believe that the owners bitterness at his

loss was fully balanced by the comfort and

good cheer which those magnificent rail

fires afforded us that December night.

They did seem providentially

provided for us.

"During the night the weather turned cold, and when we

resumed our march the ground was frozen and

the roads were simply dreadful, especially

for those of our men who had lost their

shoes the day before and were now compelled

to walk barefoot, tracking their way with

blood. Such experiences take away

something of the romance sometimes suggested

to the inexperienced by the phase,

'soldiering in the Sunny South,' but then a

touch of it is worth having for the light it

throws over such historical scenes as those

at Valley Forge.

"We continued in the pursuit of Hood, as far as

Huntsville, Ala., when he disappeared to

return no more, and we were allowed to go

back to Chattanooga, glad of an opportunity

to rest. Distance travelled, 420 miles.

"We had no more fighting. There were many interesting

experiences, which, however, I will not take

time to relate. In August, 1805, being

in command of the Post at Knoxville, Tenn.,

grateful to have escaped without

imprisonment, wounds, or even a day of

severe illness, I resigned my commission,

after forty mouths of service, to resume my

studies.

"I cannot close this paper without expressing the

conviction that history has not yet done

justice to the share borne by colored

soldiers in the war for the Union.

Their conduct during that eventful period,

has been a silent, but most potent factor in

influencing public sentiment, shaping

legislation, and fixing the status of

colored people in America. If the

records of their achievements could be put

into such shape that they could be

accessible to the thousands of colored youth

in the South, they would kindle in their

young minds an enthusiastic devotion to

manhood and liberty."

|