|

It

was not long after each army received its

quota of Phalanx soldiers, before the white

troops began regarding

them much as Napoleon's troops did

the Imperial Guard, their main support.

When a regiment of the Phalanx went

into a fight, every white soldier knew what

was meant, for the black troops took no

ordinary part in a battle. Where the

conflict was hottest; where danger was most

imminent, there the Phalanx went; and when

victory poised, as it often did, between the

contending sides, the weight of the Phalanx

was frequently thrown into the balancing

scales; if some strong work or dangerous

battery had to be taken, whether with the

bayonet alone or hand grenade or sabre, the

Phalanx was likely to be in the charging

column, or formed a part of the storming

brigade.

The confederates were no cowards; braver men never bit

cartridge or fired a gun, and when they were

to meet ''their slaves," as they believed,

in revolt, why, of course, honor forbade

them to ask or give quarter. This fact

was known to all, for, as yet, though

hundreds had been captured, none had been

found on parole, or among the exchanged

prisoners. General Grant's

attention was called to this immediately

after the fight at Milliken's Bend, where

the officers of the Phalanx, as well as

soldiers, had been captured and hung.

Grant wrote Gen. Taylor,

commanding the confederate forces in

Louisiana, as follows:

[Pg. 316]

"I feel no inclination to

retaliate for offences of irresponsible

persons, but, if it is the policy of any

general intrusted with the command of

troops, to show no quarter, or to punish

with death, prisoners taken in battle, will

accept the issue. It may be you propose a

different line of policy to black troops,

and officers commanding them, to that

practiced toward white troops. If so,

I can assure you that these colored troops

are regularly mustered into the service of

the United States. The government, and

all officers under the government, are bound

to give the same protection to these troops

that they do to any other troops."

General Taylor replied that he would

punish all such acts, "disgraceful alike to

humanity and the reputation of soldiers,"

but declared that officers of the

"Confederate Army" were required to turn

over to the civil authorities, to be dealt

with according to the laws of the State

wherein such were captured, all negroes

taken in arms.

As early as December, 1862, incensed by General

Butler's administration at New

Orleans in the arming of negroes,

Jefferson Davis, President of the

Confederate Government, issued the following

proclamation:

"FIRST. That all commissioned

officers in the command of said Benjamin

F. Butler be declared not entitled to be

considered as soldiers engaged in honorable

warfare, but as robbers and criminals,

deserving death; and that they, and each of

them, be, whenever captured, reserved for

execution.

"SECOND. That the private soldiers and non-commissioned

officers in the army of said Benj. F.

Butler, be considered as only

instruments used for the commission of

crimes, perpetrated by his orders, and not

as free agents; that they, therefore, be

treated when captured as prisoners of war,

with kindness and humanity, and be sent home

on the usual parole; that they will in no

manner aid or serve the United States in any

capacity during the continuance of war,

unless duly exchanged.

"THIRD. That all negro slaves captured in arms be at

once delivered over to the executive

authorities, of the respective States to

which they belong, and to be dealt with

according to the laws of said States.

"FOURTH. That the like orders be executed In all cases

with respect to all commissioned officers of

the United States when found serving in

company with said slaves in insurrection

against the authorities of the different

States of this Confederacy.

Signed and sealed at Richmond, Dec. 23,

1862.

JEFFERSON

DAVIS

This Proclamation was the hoisting of the

black flag against the Phalanx, by which

Mr. Davis expected to bring about

a war of extermination against the negro

soldiers.*

In his third annual message to the Confederate

Congress, Mr. Davis said:

"We

may well leave it to the instincts of that

common humanity which a beneficient creator

has implanted in the breasts of our fellow

------

* Among the captured rebel flags now in

the War Department, Washington, D. C., are

several Black Flags. No. 205 was captured

near North Mountain, Md., Aug. 1st, 1864.

Another Captured from General Pillow's

men at Fort Donelson, is also among the

rebel archives in that Department.

Several of them were destroyed by the troops

capturing them, as at Pascagoula, Miss., and

near Grand Gulf on the Mississippi.

[Pg. 317]

men of all

countries to pass judgment on a measure by

which several millions of human beings of an

inferior race peaceful and contented

laborers in their sphere are doomed to

extermination, while at the same time they

are encouraged to a general assassination of

their masters by the insiduous

recommendation to abstain from violence

unless in necessary defence. Our own

detestation of those who have attempted the

most execrable measures recorded in the

history of guilty man is tempered

by profound contempt for the impotent rage

which it discloses. So far as regards

the action of this government on such

criminals as may attempt its execution, I

confine myself to informing you that I shall

unless in your wisdom you deem some other

course expedient deliver to the several

State authorities all commissioned officers

of the United States that may hereafter be

captured by our forces in any of the States

embraced in the Proclamation, that they may

be dealt with in accordance with the laws of

those States providing for the punishment of

criminals engaged in exciting servile

insurrection. The enlisted

soldiers I shall continue to treat as

unwilling instruments in the commission of

these crimes, and shall direct their

discharge and return to their homes on the

proper and usual parole."

The

confederate Congress soon took up the

subject, and after a protracted

consideration passed the following:

"Resolved, By the

Congress of the Confederate States of

America, in response to the message of the

President, transmitted to Congress at the

commencement of the present session.

That, in the opinion of Congress, the

commissioned officers of the enemy ought not

to be delivered to the authorities of the

respective States, as suggested in the said

message,

but all captives taken by the confederate

forces, ought to be dealt with and disposed

of by the Confederate Government.

"SEC. 2. That in the judgment of Congress, the

Proclamations of the President of the United

States, dated respectively September 22nd,

1862, and January 1st, 1863, and other

measures of the Government of the United

States, and of its authorities, commanders

and forces, designed or intended to

emancipate slaves in the Confederate States,

or to

abduct such slaves, or to incite them to

insurrection, or to employ negroes in war

against the Confederate States, or to

overthrow the institution of African slavery

and bring on a servile war in these States,

would, if successful, produce atrocious

consequences, and they are inconsistent with

the spirit of those usages which, in modern

warfare, prevail among the civilized

nations; they may therefore be lawfully

suppressed by retaliation.

"SEC. 3. That in every case wherein, during the war,

any violation of the laws and usages of war

among civilized nations shall be. or has

been done and perpetrated by those acting

under the authority of the United States, on

the persons or property of citizens of the

Confederate States, or of those under the

protection or in the land or naval service

of

the Confederate States, or of any State of

the Confederacy, the Presi-

[Pg. 318]

dent of the Confederate States is hereby

authorized to cause full and and ample

retaliation to be made for every such

violation, in such manner and to such extent

as he may think proper.

"SEC. 4. That every white person, being a commissioned

officer, or acting as such, who during the

present war shall command negroes or

mulattoes in arms against the Confederate

States, or who shall arm, train, organize or

prepare negroes or mulattoes for military

service against the Confederate States, or

who shall voluntarily use negroes or

mulattoes in any military enterprise, attack

or conflict, in such service, shall be

deemed as inciting servile insurrection, and

shall, if captured, be put to death, or to

be otherwise punished at the discretion of

the court.

"SEC. 5. Every person, being a commissioned officer, or

acting as such in the service of the enemy,

who shall during the present war, excite,

attempt to excite, or cause to be excited a

servile insurrection, or who shall incite,

or cause to be incited a slave to rebel,

shall, if captured, be put to death, or

otherwise punished at the discretion of the

court."

"SEC. 6. Every person charged with an offence

punishable under the preceeding resolutions

shall, during the present war, be tried

before the military court, attached to the

army or corps by the troops of which he

shall have been captured, or by such other

military court as the President may direct,

and in such manner and under such

regulations as the President shall

prescribe; and after conviction, the

President may commute the punishment in such

manner and on such terms as he may deem

proper.

SEC. 7. All negroes and mulattoes who shall be engaged

in war, or be taken in arms against the

Confederate States, or shall give aid or

comfort to the enemies of the Confederate

States, shall, where captured in the

Confederate States, be delivered to

authorities of the State or States in which

they shall be captured, to be dealt with

according to such present or future laws of

such State or States."

In March, 1863, this same Confederate

Congress enacted the following order to

regulate the impressment of negroes for army

purposes:

"SEC. 9. Where slaves are impressed by the

Confederate Government, to labor on

fortifications, or other public works, the

impressment shall be made by said Government

according to the rules and regulations

provided in the laws of the States wherein

they are impressed; and, in the absence of

such law, in accordance with such rules and

regulations not inconsistent with the

provisions of this act, as the Secretary of

War shall from time to time prescribe;

Provided, That no impressment of slaves

shall be made, when they can be hired or

procured by the owner or agent.

"SEC. 10. That, previous to the 1st day of December

next, no slave laboring on a farm or

plantation, exclusively devoted to the

production of grain and provisions, shall be

taken for the public use, without the

consent of the owner, except in case of

urgent necessity."

[Pg. 319]

Thus it is apparent that while the

Confederate Government was holding aloft the

black flag, even against the Northern

Phalanx regiments composed of men who were

never slaves, it was at the same time

engaged in enrolling and conscripting slaves

to work on fortifications and in trenches,

in support of their rebellion against the

United States, and at a period when negro

troops were not accepted in the army of the

United States.

Soon after the admission of negroes into the Union

army, it was reported to Secretary Stanton

that three negro soldiers, captured with the

gunboat "Isaac Smith,"

on Stone river, were placed in close

confinement, whereupon he ordered three

confederate prisoners belonging to South

Carolina to be placed in close confinement,

and informed the Confederate Government of

the action. The Richmond Examiner

becoming cognizant of this said:

"It

is not merely the pretension of a regular

Government affecting to deal with 'rebels,'

but it is a deadly stab which they are

aiming at our institutions themselves;

because they know that, if we were insane

enough to yield this point, to treat black

men as the equals of white, and insurgent

slaves as equivalent to our brave white

soldiers, the very foundation of slavery

would be fatally wounded."

Several black soldiers were captured in an

engagement before Charleston, and when it

came to an exchange of prisoners, though an

immediate exchange of all captured in the

engagement had been agreed upon, the

confederates would not exchange the negro

troops. To this the President's

attention was called, whereupon he issued

the following order:

"EXECUTIVE MANSION, WASHINGTON, July 30th,

1863.

"It

is the duty of every government to give

protection to its citizens, of whatever

color, class, or condition, and especially

to those who are duly organized as soldiers

in the public service. The law of

nations and the usages and customs of war,

as carried on by civilized powers, permit no

distinction as to color in the treatment of

prisoners of war, as public enemies.

To sell or enslave any captured person, on

account of his color, and for no offense

against the laws of war, is a relapse into

barbarism, and a crime against the

civilization of the age. The

government of the United States will give

the same protection to all its soldiers; and

if the enemy shall enslave or sell any one

because of his color, the offense shall be

punished by retaliation upon the enemy's

prisoners in

[Pg. 320]

our possession. It is therefore

ordered that for every soldier of the United

States killed in violation of the laws of

war, a rebel soldier shall be executed, and

for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold

into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be

placed at hard labor on public works, and

continued at such labor until the other

shall be released and receive the treatment

due to a prisoner of war.

"ABRAHAM LINCOLN,

"By order of Secretary of War.

"E. D. TOWNSEND, Ass't. Adjt. General."

However, this order did not prevent the

carrying out of the intentions of the

confederate President and Congress.

The saddest and blackest chapter of the history of the

war of the Rebellion, is that which relates

to the treatment of Union prisoners in the

rebel prison pens, at Macon, Ga., Belle

Island, Castle Thunder, Pemberton, Libby, at

and near Richmond and Danville, Va., Cahawba,

Ala., Salisbury, N. C., Tyler, Texas,

Florida, Columbia, S. C., Millen and

Andersonville, Ga. It is not the

purpose to attempt a general description of

the modern charnel houses, or to enter into

a detailed statement of the treatment of the

Union soldiers who were unfortunate enough

to escape death upon the battle-field and

then fall captive to the confederates.

When we consider the fact that the white men

who were engaged in the war upon both sides,

belonged to one nation, and were Americans,

many of whom had been educated at the same

schools, and many very many of them members

of the same religious denominations, and

church; not a few springing from the same

stock and loins, the atrocities committed by

the confederates against the Union soldiers,

while in their custody as prisoners of war,

makes their deeds more shocking and inhuman

than if the contestants had been of a

different nationality.

The English soldiers who lashed the Sepoys to the

mouths of their cannon, and then fired the

pieces, thus cruelly murdering the captured

rebels, offered the plea, in mitigation of

their crime, and as an excuse for violating

the rules of war, that their subjects were

not of a civilized nation, and did not

themselves adhere to the laws govern-

[Pg. 321] -

BLANK PAGE -

[Pg. 322]

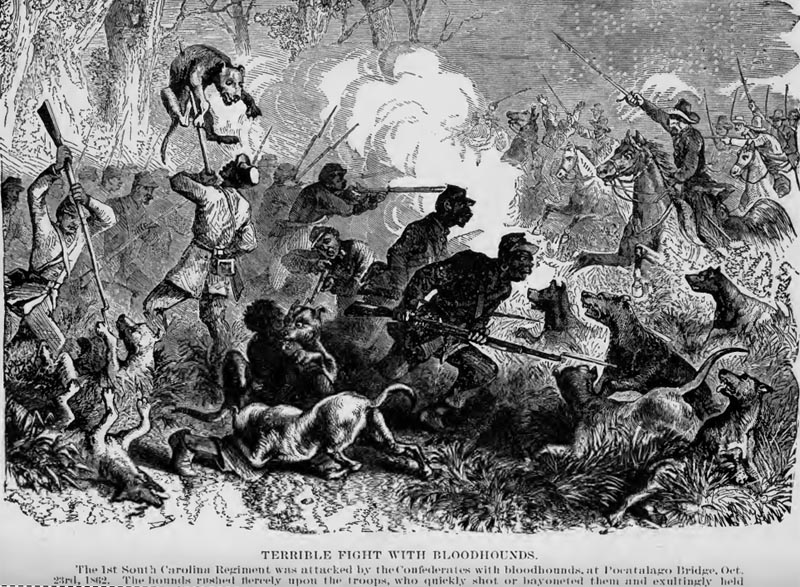

Terrible Fight With Bloodhounds.

The first South Carolina Regiment was

attacked by the Confederates with

bloodhounds, at Pocatalago Bridge, Oct.

23rd, 1862. The hounds rushed fiercely

upon the troops, who quickly shot or

bayoneted them and exultingly held ____

(missing)

[Pg. 323]

ing civilized nations at war with each

other. But no such plea can be entered

in the case of the confederates, who

starved, shot and murdered 80,000 of their

brethren in prison pens, white prisoners of

war. If such treatment was meted to

those of their own color and race, as is

related by an investigating committee of

Senators, what must have been the treatment

of those of another race. - whom they had

held in slavery, and whom they regarded the

same as sheep and horses, to be bought and

sold at will, - when captured in battle,

fighting against them for the Union and

their own freedom?

The report of the Congressional Committed furnishes

ample proof of the barbarities:

|

38TH CONGRESS,

1st Session |

} |

|

{ |

REP. COM.

No. 68 |

==========================================================

"IN THE SENATE OF THE

UNITED STATES

___________

"Report of the Joint

Committed on the Conduct and Expenditures of

the war.

"On the 4th inst., your committee

received a communication of that date from

the Secretary of War, enclosing the report

of Colonel Hoffman commissary general

of prisoners, dated May 3, calling the

attention of the committee to the condition

of returned Union prisoners, with the

request that the committee would immediately

proceed to Annapolis and examine with their

own eyes the condition of those who have

been

returned from rebel captivity. The

committee resolved that they would comply

with the request of the Secretary of War on

the first opportunity. The 5th of May

was devoted by the committee to concluding

their

labors upon the investigation of the Fort

Pillow massacre. On the 6th of May,

however, the committee proceeded to

Annapolis and Baltimore, and examined the

condition of our returned soldiers, and took

the testimony of several of them, together

with the testimony of surgeons and other

persons in attendance upon the hospitals.

That testimony, with the communication of

the Secretary of War, and the report of

Colonel

Hoffman, is herewith transmitted.

"The evidence proves, beyond all manner of doubt, a

determination on the part of the rebel

authorities, deliberately and persistently

practiced for a long time past, to subject

those of our soldiers who have been so

unfortunate as to fall in their hands to a

system of treatment which has resulted in

reducing many of those who have survived and

been permitted to return to us in a

condition, both physically and mentally,

which no language we can use can adequately

describe. Though nearly all the

patients now in the Naval Academy hospital

at Annapolis, and in

[Pg. 324]

the West hospital, in Baltimore, have been

under the kindest and most intelligent

treatment for about three weeks past, and

many of them for a greater length of time,

still they present literally the appearance

of living skeletons, many of them being

nothing but skin and bone; some of them are

maimed for life, having been frozen while

exposed to the inclemency of the winter

season on Belle Isle, being compelled to lie

on the bare ground, without tents or

blankets, some of them without overcoats or

even coats, with but little fire to mitigate

the severity of the winds and storms to

which they were exposed.

"The testimony shows that the general practice of their

captors was to rob them, as soon as they

were taken prisoners, of all their money,

valuables, blankets, and good clothing, for

which they received nothing in exchange

except, perhaps, some old worn-out rebel

clothing hardly better than none at all.

Upon their arrival at Richmond they have

been confined, without blankets or other

covering, in buildings without fire, or upon

Belle Isle with, in many cases, no shelter,

and in others with nothing but old discarded

army tents, so injured by rents and holes as

to present but little barrier to the wind

and storms; on several occasions, the

witnesses say, they have arisen in the

morning from their resting places upon the

bare earth, and found several of their

comrades frozen to death during the night,

and that many others would have met the same

fate had they not walked rapidly back and

forth, during the hours which should have

been devoted to sleep, for the purpose of

retaining sufficient warmth to preserve

life.

"In respect to the food furnished to our men by the

rebel authorities, the testimony proves that

the ration of each man was totally

insufficient in quantity to preserve the

health of a child, even had it been of

proper quality, which it was not. It

consisted usually, at the most, of two small

pieces of corn-bread, made in many

instances, as the witnesses state, of corn

and cobs ground together, and badly prepared

and cooked, of, at times, about two ounces

of meat, usually of poor quality, and unfit

to be eaten, and occasionally a few black

worm-eaten beans, or something of that kind.

Many of your men were compelled to sell to

their guards, and others, for what price

they could get, such clothing and blankets

as they were permitted to receive of that

forwarded for their use by our government,

in order to obtain additional food

sufficient to sustain life; thus, by

endeavoring to avoid one privation reducing

themselves to the same destitute condition

in respect to clothing and covering that

they were in before they received any from

our government. When they became sick

and diseased in consequence of this exposure

and privation, and were admitted into the

hospitals, their treatment was little if

any, improved as to food, though they,

doubtless, suffered less from exposure to

cold than before. Their food still

remained insufficient in quantity and

altogether unfit in quality. Their

diseases and wounds did not receive the

treatment which the commonest dictates of

humanity would have prompted. One

witness, whom your committee examined, who

had lost all the toes of one foot from being

frozen while on

[Pg. 325] -

Belle Isle, states that for days at a time

his wounds were not dressed, and they had

not been dressed for four days when he was

taken from the hospital and carried on the

flag-of-truce boat for Fortress Monroe.

"In reference fco the condition to which our men were

reduced by cold and hunger, your committee

would call attention to the following

ex-extracts

from the testimony. One witness testifies:

" 'I had no blankets until our Government sent us some.

" 'Question. How did you sleep before you received

those blankets?

" 'Answer. We used to get together just as close as we

could, and sleep spoon-fashion, so that when

one turned over we all had to turn over.

" 'Another witness testifies:

" 'Question. Were you hungry all the time?

" 'Answer. Hungry! I could eat anything that came

before us; some of the boys would get boxes

from the North with meat of different kinds

in them; and, after they had picked the meat

off, they would throw the

bones away into the spit-boxes, and we would

pick the bones out of the spit-boxes and

gnaw them over again.'

" In addition to this insufficient supply of food,

clothing and shelter, our soldiers, while

prisoners, have been subjected to the most

cruel treatment from those placed over them.

They have been abused and shamefully treated

on almost every opportunity. Many have

been mercilessly shot and killed when they

failed to comply with all the demands of

their jailors, sometimes for violating rules

of which they had not been informed.

Crowded in great numbers in buildings, they

have been fired at and killed by the

sentinels outside when they appeared at the

windows for the purpose of obtaining a

little fresh air. One man, whose

comrade in the service, in battle and in

captivity, had been so fortunate as to be

among those released from further torments,

was shot dead as he was waving with his hand

a last adieu to his friend; and other

instances of equally unprovoked murder are

disclosed by the testimony.

"The condition of our returned soldiers as regards

personal cleanliness, has been filthy almost

beyond description. Their clothes have

been so dirty and so covered with vermin,

that those who received them have been

compelled to destroy their clothing and

re-clothe them with new and clean raiment.

Their bodies and heads have been so infested

with vermin that, in some instances,

repeated washings have failed to remove

them; and those who have received them in

charge have been compelled to cut all the

hair from their heads, and make applications

to destroy the vermin. Some have been

received with no clothing but shirts and

drawers and a piece of blanket or other

outside covering, entirely destitute of

coats, hats, shoes or stockings; and the

bodies of those better supplied with

clothing have been equally dirty and filthy

with the others, many who have been sick and

in the hospital having had no opportunity to

wash their bodies for weeks and months

before they were released from captivity.

"Your committee are unable to convey any adequate idea

of the sad and deplorable condition of the

men they saw in the hospitals they

[Pg. 326]

visited; and the testimony they have taken

cannot convey to the reader the impressions

which your committee there received.

The persons we saw, as we were assured by

those in charge of them, have greatly

improved since they have been received in

the hospitals. Yet they are now dying

daily, one of them being in the very throes

of death as your committee stood by his

bed-side and witnessed the sad spectacle

there presented. All those whom your

committee examined stated that they have

been thus reduced and emaciated entirely in

consequence of the merciless treatment they

received while prisoners from their enemies;

and the physicians in charge of them, the

men best fitted by their profession and

experience to express an opinion upon the

subject, all say that they have no doubt

that the statements of their patients are

entirely correct.

"It will be observed from the testimony, that all the

witnesses who testify upon that point state

that the treatment they received while

confined at Columbia, South Carolina,

Dalton, Georgia, and other places, was

far more humane than that they received at

Richmond, where the authorities of the

so-called confederacy were congregated, and

where the power existed, had the inclination

not been wanting, to reform those abuses and

secure to the prisoners they held some

treatment that would bear a public

comparison to that accorded by our

authorities to the prisoners in our custody.

Your committee, therefore, are constrained

to say that they can hardly avoid the

conclusion, expressed by so many of our

released soldiers, that the inhuman

practices herein referred to are the result

of a determination on the part of the rebel

authorities to reduce our soldiers in their

power, by privation of food and clothing,

and by exposure, to such a condition that

those who may survive shall never recover so

as to be able to render any effective

service in the field. And your

committee accordingly ask that this report,

with the accompanying testimony be printed

with the report and testimony [which was

accordingly done] in relation to the

massacre of Fort Pillow, the one being, in

their opinion, no less than the other, the

result of a predetermined policy. As

regards the assertions of some of the rebel

newspapers, that our prisoners have received

at their hands the same treatment that their

own soldiers in the field have received,

they are evidently but the most glaring and

unblushing falsehoods. No one can for

a moment be deceived by such statements, who

will reflect that our soldiers, who, when

taken prisoners, have been stout, healthy

men, in the prime and vigor of life, yet

have died by hundreds under the treatment

they have received, although required to

perform no duties of the camp or the march;

while the rebel soldiers are able to make

long and rapid marches, and to offer a

stubborn resistance in the field.

"Your committee, finding it impossible to describe in

words the deplorable condition of these

returned prisoners, have caused photographs

to be taken of a number of them, and a fair

sample to be lithographed and appended to

their report, that their exact condition may

be known by all who examine it. Some of them

have since died.

"There is one feature connected with this

investigation, to which

[Pg. 327]

your committee can refer with pride and

satisfaction; and that is the uncomplaining

fortitude, the undiminished patriotism

exhibited by our brave men under all their

privations, even in the hour of death.

"Your committee will close their report by quoting the

tribute paid these men by the chaplin of the

hospital at Annapolis, who has ministered to

so many of them in their last moments; who

has smoothed their passage to the grave by

his kindness and attention, and who has

performed the last sad offices over their

lifeless remains. He says :

"

'There is another thing I would wish to

state. All the men, without any

exception among the thousands that have come

to this hospital, have never in a single

instance expressed a regret (notwithstanding

the privations and sufferings they have

endured) that they entered their country's

service. They have been the most

loyal, devoted and earnest men. Even

on the last days of their lives they have

said that all they hoped for was just to

live and enter the ranks again and meet

their foes. It is a most glorious

record in reference to the devotion of our

men to their country. I do not think

their patriotism has ever been equalled in

the history of the world.'

"All of which is respectfully submitted.

B. F. WADE, Chairman."

Also the following:

"OFFICE OF COMMISSARY-GENERAL OF PRISONERS.

WASHINGTON, D. C., May 3, 1864.

"SIR: - I have the honor to report that,

pursuant to your instructions of the 2nd

instant, I proceeded, yesteray morning to

Annapolis, with a view to see that the

paroled prisoners about to arrive there from

Richmond were properly received and cared

for.

"The flag-of-truce boat, 'New York,' under the charge

of Major Mulford, with thirty-two

officers, three hundred and sixty-three

enlisted men, and one citizen of board,

reached the wharf at The Naval School

hospital about ten o'clock. On going

on board, I found the officers generally in

good health, and much cheered by their happy

release from the rebel prisons, and by the

prospect of again being with their friends.

"The enlisted men who had endured so many privations at

Belle Isle and other places were, with few

exceptions, in a very sad plight, mentally

and physically, having for months been

exposed to all the changes of the

weather, with no other protection than a

very insufficient supply of worthless tents,

and with an allowance of food scarcely

sufficient to prevent starvation, even if of

wholesome quality; but as it was made of

coarsely-ground corn, including the husks,

and probably at times the cobs, if it did

not kill by starvation, it was sure to do it

by the disease it created. Some of

these poor fellows were wasted to mere

skeletons, and had scarcely life enough

remaining to appreciate that they were now

in the hands of their friends, and among

them all there were few who had not become

too much broken down and dispirited by their

many privations to be able to realize the

happy prospect of relief from their

sufferings which was before them. With

rare exception, every face was sad

[Pg. 328]

with care and hunger; there was no

brightening of the countenance or lighting

up of the eye, to indicate a thought of

anything beyond a painful sense of

prostration of mind and body. Many

faces showed that there was scarcely a ray

of intelligence left.

"Every preparation had been made for their reception in

anticipation of the arrival of the steamer,

and immediately upon her being made fast to

the wharf the paroled men were landed and

taken immediately to

the hospital, where, after receiving a warm

bath, they were furnished with a suitable

supply of new clothing, and received all

those other attentions which their sad

condition demanded. Of the whole

number, there are perhaps fifty to one

hundred who, in a week or ten days, will be

in a convalescent state, but the others will

very slowly regain their lost health.

"That our soldiers, when in the hands of the rebels,

are starved to death, cannot be denied.

Every return of the flag-of-truce boat from

City Point brings us too many living and

dying witnesses to admit of a doubt of this

terrible fact. I am informed that the

authorities at Richmond admit the fact, but

excuse it on the plea that they give the

prisoners the same rations they give their

own men. But can this be so? Can

an army keep the field, and be active and

efficient, on the same fare that kills

prisoners of war at a frightful percentage?

I think not; no man can believe it; and

while a practice so shocking to humanity is

persisted in by the rebel authorities, I

would very respectfully urge that

retaliatory measures be at once instituted

by subjecting the officers we now hold as

prisoners of war to a similar treatment.

"I took advantage of the opportunity which this visit

to Annapolis gave me to make a hasty

inspection of Camp Parole, and I am happy to

report that I found it in every branch in a

most commendable condition. The men

all seemed to be cheerful and in fine

health, and the police inside and out was

excellent. Colonel Root,

the commanding officer, deserves much credit

for the very satisfactory condition to which

he has brought his command.

"I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your

obedient servant,

W. HOFFMAN,

"Colonel 3rd Infantry, Commissary General of

Prisoners.

"Hon. E. M. STANTON, Secretary of War,

Washington, D. C"

This report does not refer to the treatment of the

soldiers of the Phalanx who were taken by

the confederates in battle,* after the

surrender of Fort Pillow, Lawrence

---------------

* General

Brisbin, in his account of the

expedition which, in the Winter of 1864,

left Bean Station, Tenn., under command of

General Stoneman, for the

purpose of destroying the confederate Salt

Works in West Virginia, says the

confederates after capturing some of the

soldiers of the Sixth Phalanx Cavalry

Regiment, butchered them. His

statement is as follows :

"For the last two days a force of Confederate cavalry,

under Witcher, had been following our

command picking up stragglers and worn-out

horses in our rear. Part of our troops

were composed of negroes and these the

Confederates killed as fast as they

[Pg. 329]

and Plymouth,

and at several other places. It is

inserted to enable the reader to form an

opinion as to what the negro soldier's

treatment must have been. The same

committee also published as a part of their

report, the testimony of a number, mostly

black, soldiers, who escaped death at Fort

Pillow; a few of their statements are given:

|

38TH CONGRESS,

1st Session. |

|

|

|

REP. COM.

No. 63 & 68. |

IN THE SENATE OF THE

UNITED STATES.

Report of the Joint

Committee on the Conduct and Expenditures of

the War to whom was Referred the Resolution

of Congress Instructing

them to Investigate the late Massacre at

Fort Pillow.

"Deposition of John Nelson in

relation to the capture of Fort Pillow.

"John Nelson, being duly sworn, deposeth and saith :

" 'At the time of the attack on and capture of Fort

Pillow, Apr. 12, 1864, I kept a hotel within

the lines at Fort Pillow, and a short

distance from the works. Soon after

the alarm was given that an attack on the

fort was imminent, I entered the works and

tendered my services to Major Booth,

commanding. The attack began in the

morning at about 5˝

o'clock, and about 1 o'clock P. M.

a flag of truce approached. During

---------------

caught them, laying the dead bodies by the

roadside with pieces of paper pinned to

their clothing, on which were written such

warnings as the following: 'This is

the way we treat all nigger soldiers,' and,

'This is the fate of nigger soldiers who

fight against the South.' We did not

know what had been going on in our rear

until we turned about to go back from

Wytheville, when we found the dead colored

soldiers along the road as above described.

General Burbridge was very angry and

wanted to shoot a Confederate prisoner for

every one of his colored soldiers he found

murdered, and would undoubtedly have done so

had he not been restrained. As it was,

the whole corps was terribly excited by the

atrocious murders committed by Witcher's

men, and if Witcher had been caught

he would have been shot."

This gallant soldier, (?) twenty years after the close

of the war, writes about the incidents and

happenings during the march of the army to

Saltville, and says:

"Before we reached Marion we encountered

Breckenridge's advance and charged it

vigorously driving it back in confusion

along the Marion and Saltville road for

several miles. In one of these charges

(for there were several of them and a sort

of running fight for several miles) one of

Witcher's men was captured and

brought in. He was reported to me and

I asked him what his name was and to what

command he belonged. He gave me his

name and said 'Witcher's command.'

Hardly were the words out of his mouth

before a negro soldier standing near raised

his carbine and aimed at the Confederate

soldier's breast. I called out and

sprang forward, but was too late to catch

the gun. The negro fired and the poor

soldier fell badly wounded. Instantly

the negro was knocked down by our white

soldiers, disarmed and tied. I drew my

revolver to blow his brains out for his

terrible crime, but the black man never

flinched. All he said was, pointing to

the Confederate soldier, 'He killed my

comrades; I have killed him.' The

negro was taken away and put among the

prisoners. The Provost Marshal had

foolishly changed the white guard over the

prisoners and placed them under some colored

troops. An officer came galloping

furiously to the front and said the negroes

were shooting the prisoners.

General Burbridge told me to go

back quickly and do whatever I pleased in

his name to restore order. It was a

lively ride, as the prisoners were more than

four miles back, being forced along the road

as rapidly as possible toward Marion.

All the prisoners, except a few wounded men,

were on foot, and of course they could not

keep up with the cavalry. I soon

reached them and never shall I forget that

sight while I live. Men with sabres

were driving the poor creatures along the

road like beasts. I halted the motley

crew and scolded the officer for his

inhumanity. He said he had orders to

keep the prisoners up with the column and he

was simply trying to obey his orders.

As I was General Burbridge's

chief of staff and all orders were supposed

to emanate from my office, I thought I had

better not continue the conversation.

As it was, I said such orders were at an end

and I would myself take charge of the

prisoners."

[Pg. 330]

the parley which ensued, and while the

firing ceased on both sides, the rebels kept

rowding up to the works on the side near

Cold Creek, and also approached nearer on

the south side, thereby gaining advantages

pending the conference under the flag of

truce. As soon as the flag of truce

was withdrawn the attack began, and about

five minutes after it began the rebels

entered the fort. Our troops were soon

overpowered and broke and fled. A

large number of the soldiers, black and

white, and also a few citizens, myself among

the number, rushed down the bluff toward the

river. I concealed myself as well as I

could in a position where I could distinctly

see all that passed below the bluff, for a

considerable distance up and down the river.

" 'A large number, at least one hundred, were hemmed in

near the river bank by bodies of the rebels

coming from both north and south. Most

all of those thus hemmed in were without

arms. I saw many soldiers, both white

and black, throw up their arms in token of

surrender, and call out that they had

surrendered. The rebels would reply, 'G__d

d__n you, why didn't you surrender before?'

and shot them down like dogs.

" 'The rebels commenced an indiscriminate slaughter.

Many colored soldiers sprang into the river

and tried to escape by swimming, but these

were invariably shot dead.

" 'A short distance from me, and within view, a number

of our wounded had been placed, and near

where Major Booth's body lay; and a

small red flag indicated that at that place

our wounded were placed. The rebels

however, as they passed these wounded men,

fired right into them and struck them with

the butts of their muskets. The cries

for mercy and groans which arose from the

poor fellows were heartrending

" 'Thinking that if I should be discovered, I would be

killed, I emerged from my hiding place, and,

approaching the nearest rebel, I told him I

was a citizen. He said, 'You are in

bad company, G_d d__n you; out with your

greenbacks, or I'll shoot you.' I gave

him all the money I had, and under his

convoy I went up into the fort again.

" 'When I re-entered the fort there was still some

shooting going on. I heard a rebel

officer tell a soldier not to kill any more

of those negroes. He said that they

would all be killed, any way, when they were

tried.

" 'After I entered the fort, and after the United

States flag had been taken down, the rebels

held it up in their hands in the presence of

their officers, and thus gave the rebels

outside a chance to still continue their

slaughter, and I did not notice that any

rebel officer forbade the holding of it up.

I also further state, to the best of my

knowledge and information, that there were

not less than three hundred and sixty

negroes killed and two hundred whites.

This I give to the best of my knowledge and

belief.

JOHN NELSON.

'Subscribed and

sworn to before me this 2nd day of May, A.

D.1864.

"J. D. LLOYD,

"Capt. 11th Inf., Mo. Vols., and As't.

Provost Mar., Dist. of Memphis."

[Pg. 331]

"Henry Christian, (colored), private,

company B, 6th United States heavy

artillery, sworn and examined. By

Mr. Gooch:

'Question. Where were you raised? 'Answer.

In East Tennessee.

'Question. Have you been a slave? 'Answer.

Yes, sir.

'Question. Where did you enlist? 'Answer.

At Corinth, Mississippi.

'Question. Where you in the fight at Fort Pillow?

'Answer. Yes, sir.

'Question. When were you wounded? 'Answer.

A little before we surrendered.

'Question. What happened to you afterwards?

'Answer. Nothing; I got but one shot, and

dug right out over the hill to the river,

and never was bothered any more.

'Did you see any men shot after the place was taken?

'Answer. Yes, sir.

'Question. Where? 'Answer. Down to

the river.

'Question. How many? 'Answer. A good

many; I dont know how many.

'Question. By whom were they shot? 'Answer.

By secesh soldiers; secesh officers shot

some up on the hill.

'Question. Did you see those on the hill shot by

the officers? 'Answer. I saw two

of them shot.

'Question. What officers were they?

'Answer. I don't know whether he was a

lieutenant or captain.

'Question. Did the men who were shot after they

had surrendered have arms in their hands?

'Answer. No, sir; they threw down

their arms.

'Question. Did you see any shot the next morning?

'Answer. I saw two shot; one was shot

by an officer - he was standing, holding the

officer's horse, and when the officer came

and got his horse he shot him dead.

The officer was setting fire to the houses.

'Question. Do you say the man was holding the

officer's horse, and when the officer came

and took his horse he shot the man down?

'Answer. Yes, sir; I saw that with my

own eyes; and then I made away into the

river, right off.

Question. Did you see any buried alive?

'Answer. I did not see any buried

alive.

"Jacob Thompson, (colored), sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

'Question. Were you a soldier at Fort Pillow?

'Answer. No, sir, I was not a soldier;

but I went up in the fort and fought with

the rest. I was shot in the hand and

the head.

'Question. When were you shot? 'Answer.

After I surrendered.

'Question. How many times were you shot?

'Answer. I was shot but once; but I

threw my hand up, and the shot went through

my hand and my head.

'Question. Who shot you? 'Answer. A

private.

'Question. What did he say? 'Answr.

He said, 'G_d d__n you,

[Pg. 332]

I will shoot you, old friend.'

'Question. Did you see anybody else shot?

'Answer. Yes, sir; they just called

them out like dogs and shot them down.

I recon they shot about fifty, white and

black, right there. they nailed some

black sergeants to the logs, and set the logs

on fire.

'Question. When did you see that? 'Answer.

When I went there in the morning I saw them;

they were burning all together.

'Question. Did they kill them before they burned

them/ 'Answer. No. sir, they

nailed them to the logs; drove the nails

right through their hands.

'Question. How many did you see in that

condition? 'Answer. Some four or

five; I saw two white men burned.

'Question. Was there any one else there who saw

that? Answer. I recon there was;

I could not tell who.

'Question. When was it that you saw them?

'Answer. I saw them in the morning

after the fight; some of them were burned

almost in two. I could tell they were

white men, because they were whiter than the

colored men.

'Question. Did you notice how they were nailed?

'Answer. I saw one nailed to the side

of a houe; he looked like he was nailed

right through his wrist. I was trying

then to get to the boat when I saw it.

"Question. Did you see them kill any white men?

'Answer. They killed some eight or

nine there. I recon they killed more

than twenty after it was all over; called

them out from under the hill and shot the

down. They would call out a white man

and shoot him down, and call out a colored

man and shoot him down; do it just as fast

as they could make their guns go off.

'Question. Did you see any rebel officers about

there when this was going on? 'Answer.

Yes, sir; old Forrest was one.

'Question. Did you know Forrest?

'Answer. Yes sir; he was a little bit

of a man. I had seen him before a

Jackson.

'Question. Are you sure he was there when this

was going on? 'Answer. Yes, sir.

'Question. Did you see any other officers that

you knew? 'Answer. I did not

know any other but him. There were

some two or three more officers came up

there.

'Question did you see any buried there? 'Answer.

Yes, sir; they buried right smart of them.

They buried a great many secesh, and a great

many of our folks. I think they buried

more secesh than our folks.

'Question. How did they bury them? 'Answer.

They buried the secesh over back of the

fort, all except those on Fort hill; them

they buried up on top of the hill where the

gunboats shelled them.

'Question. Did they bury any alive?

'Answer. I heard the gun-boat men say they

dug two out who were alive.

'Question. You did not see them? 'Answer.

No, sir.

'What company did you fight with?

'Answer. I went right into the fort

and fought there.

[Pg. 333]

'Question. Were you a slave or a free man? 'Answer.

I was a slave.

'Question.

Where were you raised ? 'Answer. In old

Virginia.

'Question.

Who was your master? 'Answer. Colonel

Hardgrove.

'Question. Where did you live? 'Answer. I

lived three miles the other side of Brown's

mills.

'Question.

How long since you lived with him? 'Answer.

I went home once and staid with him a while,

but he got to cutting up and I came away

again.

'Question.

What did you do before you went into the

fight? 'Answer. I was cooking for Co.

K, of Illinois cavalry; I cooked for that

company nearly two years.

'Question.

What white officers did you know in our

army? 'Answer. I knew Captain

Meltop and Colonel Ransom;

and I cooked at the hotel at Fort Pillow,

and Mr. Nelson kept it. I and

Johnny were cooking together.

After they shot me through the hand and

head, they beat up all this part of my head

(the side of his head) with the breach of

their guns.

"Ransome Anderson, (colored), Co. B, 6th United States

heavy artillery, sworn and examined.

By Mr. Gooch:

'Question.

Where were you raised? 'Answer.

In Mississippi.

'Question.

Were you a slave? 'Answer. Yes,

sir.

'Question.

Where did you enlist? 'Answer. At

Corinth.

'Question.

Were you in the fight at Fort Pillow?

'Answer. Yes,, sir.

'Question.

Describe what you saw done there.

'Answer. Most all the men that were

killed on our side were killed after the

fight was over. They called them out

and shot them down. Then they put some

in the houses and shut them up, and then

burned the houses.

'Question.

Did you see them burn? 'Answer.

Yes, sir.

'Question.

Were any of them alive? 'Answer. Yes,

sir; they were wounded, and could not walk.

They put them in the houses, and then burned

the houses down.

'Question.

Do you know they were in there?

'Answer. Yes, sir; I went and looked

in there.

'Question.

Do you know they were in there when the

house was burned? 'Answer. Yes,

sir; I heard them hallooing there when the

houses were burning.

'Question.

Are you sure they were wounded men, and not

dead, when they were put in there?

'Answer. Yes, sir; they told them they

were going to have the doctor see them, and

then put them in there and shut them up, and

burned them.

'Question.

Who set the house on fire? 'Answer.

I saw a rebel soldier take some grass and

lay it by the door, and set it on fire.

The door was pine plank, and it caught easy.

'Question.

Was the door fastened up? 'Answer.

Yes, sir; it was barred with one of those

wide bolts.

[Pg. 334]

"James Walls, sworn and examined.

by Mr. Gooch:

'Question.

To what company did you belong?

'Answer. Company E, 13th Tennessee

cavalry.

'Question. Under what officers did you serve?

'Answer. I was under Major Bradford

and Captain Potter.

'Question. Were you in the fight at Fort

Pillow? 'Answer. Yes, sir.

'Question. State what you saw there of the fight,

and what was done after the place was

captured. 'Answer. We fought

them for some six or eight hours in the

fort, and when they charged, our men

scattered and ran under the hill; some

turned back and surrendered, and were shot.

After the flag of truce came in I went down

to get some water. As I was coming

back I turned sick, and laid down behind a

log. The secesh charged, and after

they came over I saw one go a good ways

ahead of the others. One of our men

made to him and threw down his arms.

The bullets were flying so thick there I

thought I could not live there, so I throw

down my arms and surrendered. He did

not shoot me then, but as I turned around he

or some other one shot me in the back.

'Question. Did they say anything while they were

shooting? 'Answer. All I heard

was, 'Shoot him, shoot him!' 'Younder

goes one!' 'Kill him, kill him!'

That is about all I heard.

'Question. How many do you suppose you saw shot

after they surrendered? 'Answer.

I did not see but two or three shot around

me. One of the boys of our company,

named Taylor, ran up there, and I saw

him shot and fall. Then another was

shot just before me, like - shot down after

he threw down his arms.

'Question. Those were white men? 'Answer.

Yes, sir. I saw them make lots of

niggers stand up, and then they shot them

down like hogs. The next morning I was

lying around there waiting for the boat to

come up. The secesh would be prying

around there, and would come to a nigger and

say, 'You ain't dead are you?' They

would not say anything, and then the secesh

would get down off their horses, prick them

in their sides, and say, 'D__n you, you aint

dead; get up' Then they would make

them get up on their knees, when they would

shoot the down like hogs.

'Question. Do you know of their burning any

buildings? 'Answer. I could hear

them tell them to stick torches all around,

and they fired all the buildings.

'Question. Do you know whether any of our men

were in the buildings when they were burned?

'Answer. Some of our men said some

were burned; I did not see it, or know it to

be so myself.

'Question. How did they bury them white and black

together? ''Answer. I don't know

about the burying; I did not see any buried.

'Question. How many negroes do you suppose were

killed after the surrender? 'Answer.

There were hardly any killed before the

surrender. I reckon as many as 200

were killed after the surrender, out of

about 300 that were there.

[Pg. 335]

Question. did you see any rebel

officers about while this shooting was going

on? 'Answer. I do not know as I

saw any officers about when they were

shooting the negroes. A captain ame to

me a few minutes after I was shot: he was

close by me when I was shot.

'Question. Did he try to stop the shooting?

'Answer. I did not hear a word of

their trying to stop it. After they

were shot down, he told them not to shoot

then any more. I begged him not to let

them shoot me again, and he said they would

not. One man, after he was shot down,

was shot again. After I was shot down,

the man I surrendered to went around the

tree I was against and shot a man, and then

came around to me again and wanted my

pocket-book. I handed it up to him,

and he saw my watch-chain and made a grasp

at it, and got the watch and about half the

chain. He took an old Barlow

knife I had in my pocket. It was not

worth five cents; was of no account at all,

only to cut tobacco with."

"Nathan G. Fulks, sworn and examined. By

Mr. Gooch:

'Question. To what company and regiment do you

being? 'Answer. To Company D,

13th Tennessee cavalry.

'Question. Where are you from? 'Answer.

About twenty miles from Columbus, Tennessee.

'Question. How long have you been in the service?

'Answer. Five months, the 1st of May.

'Question. Were you at Fort Pillow at the time of

the fight there? Answer. Yes,

sir.

'Question. Will you state what happened to you

there? 'Answer. I was at the

corner of the fort when they fetched in a

flag for a surrender. Some of them

said the major stood a while, and then said

he would not surrender. They continued

to fight a while; and after a time the major

started and told us to take care of

ourselves, and I hand twenty more men broke

for the hollow. They ordered us to

halt, and some of them said, 'God d__n em,

kill 'em!' I said, 'I have

surrendered.' I had thrown my gun away

then. I took off my cartridge-box and

gave it to one of them, and said, 'Don't

shoot me;' but they did shoot me, and hit

just about where the shoe comes up on my

leg. I begged them not to shoot me,

and he said, 'God d-_n you, you fight with

the niggers, and we will kill the last one

of you!' Then they shot me in the

thick of the thigh, and I fell; and one set

out to shoot me again, when another one

said, 'Don't shoot the white fellows any

more.'

'Question. Did you see any person shot besides

yourself? 'Answer. I didn't see

them shot. I saw one of our fellows

dead by me.

'Question. Did you see any buildings burned?

'Answer. Yes, sir. While I was

in the major's headquarters they commenced

burning the buildings, and I begged one of

them to take me out and not let us burn

there; and he said, 'I am hunting up a piece

of yellow flag for you.' I think we

would have whipped them if the flag of truce

had not come in. We would have whipped

them if we had not let them get the

dead-wood on us. I was told that they

made their movement while the flag of truce

[Pg. 336]

was in. I did not see it myself,

because I had sat down, as I had been

working so hard.

'Question. How do you know they made their movement

while the flag of truce was in?

'Answer. The men that were above said

so. The rebs are bound to take every

advantage of us. I saw two more white

men close to where I was lying. That

makes three dead ones, and myself wounded."

Later on during the war the policy of massacring was

somewhat abated, that is it was not done on

the battlefield. The humanity of the

confederates in Virginia permitted them to

take their black prisoners to the rear.

About a hundred soldiers belonging to the

7th Phalanx Regiment, with several of their

white officers, were captured at Fort Gilmer

on the James River, Va., and taken to

Richmond in September, 1864. The

following account is given of their

treatment in the record of the Regiment:

"The following

interesting sketches of prison-life, as

experienced by two officers of the regiment,

captured at Fort Gilmer, have been kindly

furnished. The details of the

sufferings of the enlisted men captured with

them we shall never know, for few of them

ever returned to tell the sad story.

" 'An escort was soon formed to conduct the prisoners

to Richmond, some seven or eight miles

distant, and the kinder behavior of that

part of the guard which had participated in

the action was suggestive of the freemasonry

that exists between brave fellows to

whatever side belonging. On the road

the prisoners were subjected by every

passer-by, to petty insults, the point in

every case, more or less obscene, being the

color of their skin. The solitary

exception, curiously enough, being a

nymph du pave in the suburbs of the

town.*

" 'About dusk the prisoners reached the notorious

Libby, where the officers took leave of

their enlisted comrades from most of them

forever. The officers were then

searched and put collectively in a dark

hole, whose purpose undoubtedly was similar

to that of the 'Ear of Uionysius.' In

the morning, after being again searched,

they were placed among the rest of the

confined officers, among whom was Capt.

Cook, of the Ninth, taken a few weeks

previously at Strawberry Plains. Some

time before, the confederates had made a

great haul on the Weldon Railroad, and the

prison was getting uncomfortably full of

prisoners and vermin. After a few days

sojourn in Libby, the authorities prescribed

a

change of air, and the prisoners were packed

into box and stock cars and rolled to

Salisbury, N. C. The comforts of this

two day's ride are

---------------

* "When the

successful attempt was made, by tunneling,

to escape from Libby

Prison in 1862, many of the fugitives were

honorably harbored by this unfortunate class

till a more quiet opportunity occurred for

leaving the city. This I have from one

of the escaped officers."

[Pg. 337]

remembered as strikingly similar to

those of Mr. Hog from the West

to the Eastern market before the invention

of the S. F. P. C. T. A.

" 'At Salisbury the prisoners were stored in the

third story of an abandoned tobacco factory,

occupied on the lower floors by political

prisoners, deserters, thieves and spies, who

during the night made an attempt on the

property of the new-comers, but were

repulsed after a pitched battle. In

the morning the Post-Commandant ordered the

prisoners to some unusued negro quarters in

another part of the grounds, separated from

the latter by a line of sentries.

During the week trainloads of prisoners

enlisted men arrived and were corralled in

the open grounds. The subsequent

sufferings of these men are known to the

country, a parallel to those of

Andersonville, as the eternal infamy of

Wirtz is shared by his confrere at

Salisbury - McGee.

" 'The

weakness, and still more, the appalling

ferocity of the guards, stimulated the

desire to escape; but when this had become a

plan it was discovered, and the commissioned

prisoners were at once hurried off to

Danville, Va., and there assigned the two

upper floors of an abandoned tobacco

warehouse, which formed one side of an open

square. Here an organization into

messes was effected, from ten to eighteen in

each to

facilitate the issue of rations. The

latter consisted of corn-bread and boiled

beef, but gradually the issues of meat

became like angels' visits, and then for

several months ceased altogether. It was the

art of feeding as practised by the Hibernian

on his horse only their exchange deprived

the prisoners of testing the one straw per

day.

"Among the democracy of hungry bellies there were a few

aristocrats, with a Division General of the

Fifth Corps as Grand Mogul, whose Masonic or

family connections in the South procured

them special privileges. On the upper

floor these envied few erected a cooking

stove, around which they might be found at

all hours of the day, preparing savory

dishes, while encircled by a triple and

quadruple row of jealous noses, eagerly

inhailing the escaping vapors, so conducive

to day-dreams of future banquets. The

social equilibrium was, however,

bi-diurnally restored by a common pursuit a

general warfare under the black flag against

a common enemy, as insignificant

individually as he was collectively

formidable an insect, in short, whose

domesticity on the human body is, according

to some naturalists, one of the differences

between our species and the rest of

creation. This operation, technically,

'skirmishing,' happened twice a day,

according as the sun illumined the east or

west sides of the apartments, along which

the line was deployed in its beams.

"Eating, sleeping, smelling and skirmishing

formed the routine of prison-life, broken

once in a while by a walk, under escort, to

the Dan river, some eighty yards distant,

for a water supply. Generally, some

ten or twelve prisoners with buckets were

allowed to go at once, and this

circumstance, together with the fact that

the guard for all the prisons in

town were mounted in the open square in

front, excited the first idea of escape.

According to high diplomatic authority,

empty stomachs are

[Pg. 338]

conducive to ingenuity, so the idea soon

became a plan and a conspiracy. While

the new guard had stacked arms in the open

square preparatory to mounting, some ten or

twelve officers, under the lead of Col.

Ralston, the powerful head of some

New York regiment, were to ask for exit

under pretense of getting water, and then to

overpower the opposing sentries, while the

balance of the prisoners, previously drawn

up in line at the head of the short

staircase leading direct to the exit door,

were to rush down into the square, seize the

stacked arms and march through the

Confederacy to the Union lines perhaps!

'' 'Among the ten or twelve psuedo-water-carriers the

forlorn hope were Col. Ralston,

Capt. Cook, of the Ninth, and

one or two of the Seventh Capt.

Weiss and Lieut. Spinney.

On the guard opening the door for egress,

Col. Ralston and one of the

Seventh threw themselves on the first man, a

powerful six-footer, and floored him.

At the same moment, however, another guard

with great presence of mind, slammed the

door and turned the key, and that before

five officers could descend the short

staircase. The attempt was now a

failure. One of the guards on the

outside of the building took deliberate aim

through the open window at Col.

Ralston, who was still engaged with the

struggling fellow, and shot him through the

bowels. Col. Ralston

died a lingering and painful death after two

or three days. Less true bravery than

his has been highly sung in verse.

" 'This attempt could not but sharpen the discipline of

the prison, but soon the natural humanity of

the commandant, Col. Smith,

now believed to be Chief Engineer of the

Baltimore Bridge Company, asserted itself,

and things went on as before. Two

incidents may, however, be mentioned in this

connection, whose asperities time has

removed, leaving nothing but their salient

grotesque features.

" 'Immediately after the occurrence, an unlimited

supply of dry-salted codfish was introduced.

This being the first animal food for weeks,

was greedily devoured in large quantities,

mostly raw producing a raging thirst.

The water supply was now curtailed to a few

bucketsful, but even these few drops of the

precious fluid were mostly wasted in the

melee for their possession. The

majority of the contestants retired

disappointed to muse on the comforts of the

Sahara Desert, and as the stories about

tapping camels recurred to them, suggestive

glances were cast at the more fortunate

rivals. After a few days, conspicuous

for the sparing enjoyment of salt cod, the

water supply was ordered unlimited. An

immediate 'corner' in the Newfoundland

staple took place, the stock being actively

absorbed by bona fide investors, who

found that it bore watering with impunity.

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

" 'At the beginning of February, 1865,

thirty boxes of provisions, etc., from

friends in the North arrived for the

prisoners. The list of owners was

anxiously scanned and the lucky possessor

would not have exchanged for the capital

prize in the Havana lottery. The poor

fellows of

[Pg. 339]

the Seventh

were among the fortunate, and from that day

none knew hunger more.

" 'With the advent of the boxes came the dawn of a

brighter day. Cartels of exchange were

talked about, and by the middle of February

the captives found themselves on the rail

for Richmond. The old Libby appeared

much less gloomy than on first acquaintance,

the rays of hope throwing a halo about

everywhere. Many asked and obtained

the liberty of the town to lay in a supply

of those fine brands of tobacco for which

Richmond is famous. In a few days the

preliminaries to exchange were completed,

and on the 22d of February Washington's

birthday the captives also stepped into a

new life under the old flag."

"Captain Sherman, of Co. C., gives the following

account:

" 'Further resistance being useless, and having

expressed our willingness to surrender, we

were invited into the fort. As I

stepped down from the parapet I was

immediately accosted by one of the so-called

F. F. V.'s, whose smiling countenance and

extended hand led me to think I was

recognized as an acquaintance. My mind

was soon disabused of that idea, however,

for the next instant he had pulled my watch

from its pocket, with the remark, 'what have

you there?' Quick' as thought, and

before he could realize the fact, I had

seized and recovered the wratch, while he

held only a fragment of the chain, and

placing it in an inside pocket, buttoned my

coat and replied, 'that is my watch and you

cannot have it.'

" 'Just then I discovered Lieut. Ferguson was receiving

a good deal of attention a crowd having

gathered about him and the next moment saw

his fine new hat had been appropriated by

one of the rebel soldiers, and he stood

hatless. Seeing one of the rebel

officers with a Masonic badge on his coat,

Lieut. F. made himself known as a

brother Mason, and appealed to him for

redress. The officer quickly responded

and caused the hat to be returned to its

owner, only to be again stolen, and the

thief made to give it up as before.

" 'In a little while we (seven officers and eighty-five

enlisted men) were formed in four ranks, and

surrounded by a guard, continued the march

'on to Richmond' but under very different

circumstances from what we had flattered

ourselves would be the case, when only two

or three hours before our brigade-commander

had remarked, as he rode by the regiment,

that we would certainly be in Richmond that

night. We met a great many civilians,

old and young, on their way to the front, as

a general alarm had been sounded in the

city, and all who could carry arms had been

ordered to report for duty in the

intrenchments. After a few miles march

we halted for a rest, but were not allowed

to sit down, as I presume the guards thought

we could as well stand as they. Here a

squad of the Richmond Grays, the elite of

the city, came up and accosted us with all

manner of vile epithets. One of the

most drunken and boisterous approached

within five or six feet of me, and with the

muzzle of his rifle within two feet of my

face swore he would shoot me. Fearless

of consequences, and feeling that immediate

death even could not be worse

[Pg. 340]

than slow

torture by starvation, to which I knew that

so many of our soldiers had been subjected,

and remembering that the Confederate

Congress had declared officers of colored

troops outlaws, I replied, as my eyes met

his, 'shoot if you dare.' Instead of

carrying out his threat he withdrew his aim

and staggered on. Here Lieut.

Ferguson lost his hat, which had been

already twice stolen and recovered.

One of the rebs came up behind him and

taking the hat from his head replaced it

with his own and ran off. The

lieutenant consoled himself with the

reflection that at last he had a hat no one

would steal.

" 'At about 7 P. M. we arrived at Libby Prison

and were separated from

the enlisted men, who, we afterward learned,

suffered untold hardships, to which many of

them succumbed. Some were claimed as slaves

by men who had never known them; others

denied fuel and shelter through the winter,

and sometimes water with which to quench

their thirst; the sick and dying neglected

or maltreated and even murdered by

incompetent and fiendish surgeons; without

rations for days together; shot at without

the slightest reason or only to gratify the

caprice of the guards, all of which

harrowing details were fully corroborated by

the few emaciated wrecks that survived.

" 'We were marched

inside the prison, searched, and what money

we had taken from us. I was allowed to