|

The

BLACK PHALANX;

A History of the

NEGRO SOLDIERS OF THE UNITED STATES

in the Wars of

1775-1812, 1861-'65,

By

Joseph T. Wilson

Late of the 2nd Reg't. La. Native Guard Vols. 54th Mass. Vols.

Aide-De-camp to the Commander-In-Chief G. A. R.

Author of

"Emancipation," "Voice of a New Race," "Twenty-Two Years of

Freedom," etc., etc.

-----

56 Illustrations

-----

Hartford, Conn.:

American Publishing Company

1890

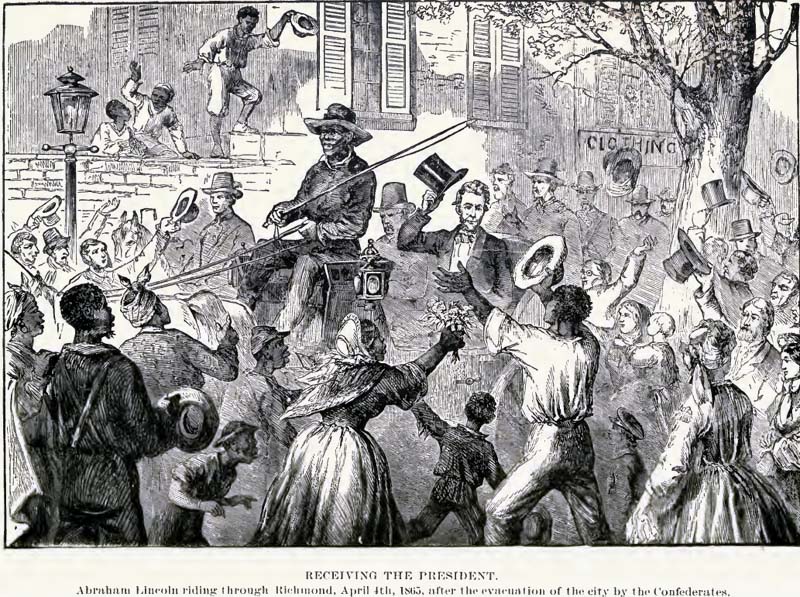

CHAPTER XI. -

THE PHALANX IN VIRGINIA.

pg. 377 - 462

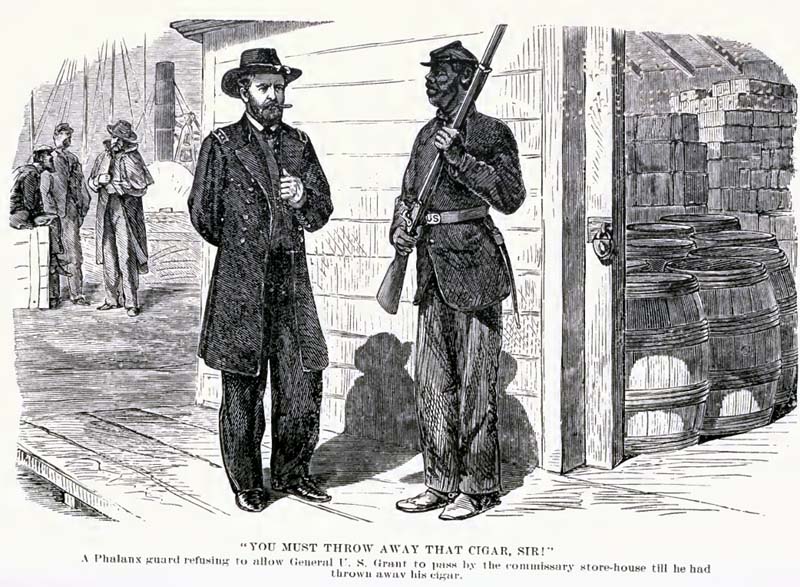

The laurels won by the

Phalanx in the Southern States, notwithstanding the "no quarter"

policy, was proof of its devotion to the cause of liberty and the

old flag, which latter, until within a short period had been but a

symbol of oppression to the black man; Cailloux has reddened

it with his life's blood, and Carney in a seething fire had

planted it on the ramparts of Wagner. The audacious bravery of

the Phalanx had wrung form Generals Banks and Gillmore

congratulatory orders, while the loyal people of the nation poured

out unstinted praises. Not a breach of discipline marred the

negro soldier's record; not one cowardly act tarnished their fame.

Grant pronounced them gallant and reliable, and Weitzel

was willing to command them.

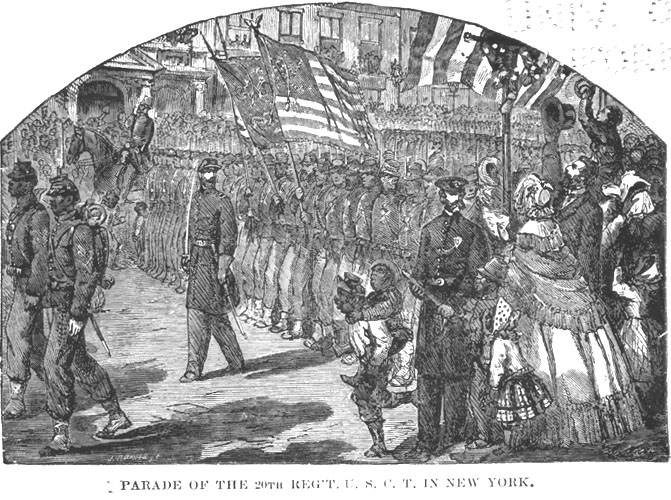

In New York City, where negroes had been hung to lamp

posts, and where a colored orphan asylum had been sacked and burned,

crowds gathered in Broadway and cheered Phalanx regiments on their

way to the front. General Logan, author of the

Illinois Black Code, greeted them as comrades, and Jefferson

Davis finally accorded to them the rights due captured

soldiers as prisoners of war. Congress at last took up the

question of pay, and placed the black on an equal footing with the

white soldiers. Their valor, excelled by no troops in the

field, had finally won full recognition from every quarter, and

henceforth they were to share the full glory as well as the toils of

their white comrades-in-arms. Not until those just

[Page 378]

rights and attentions were

attained, was the Phalanx allowed, to any great extent, to show its

efficiency and prowess in the manoeuvres in Virginia and vicinity,

where that magnificent "Army of Northern Virginia," the hope and the

pride of the Confederacy, was operating against the Federal

government. But when General Grant came to

direct the movements of the Eastern armies of the United States,

there was a change. He had learned from his experience at

Vicksburg and other places in his western campaigns, that the negro

soldiers were valuable; that they could be fully relied upon in

critical times, and their patriotic zeal had made a deep impression

upon him. Therefore, as before stated, there were changes, and

quite a good many Phalanx regiments - numbering about 20,000 men -

were taken from Southern and Western armies and transferred to the

different armies in Virginia. The 19th Army Corps sent one

brigade. General Gillmore brought a brigade from

the Tenth Army Corps. At least ten thousand of them were

veterans, and had driven many confederates out of their breastworks.

The world never saw such a spectacle as America

presented in the winter and early spring of 1864. The attempt to

capture Richmond and Petersburg had failed.

The Army of the Potomac lay like a weary lion under cover, watching

its opponent. Bruised, but spirited and defiant, it had

driven, and in turn had been driven time and again, by its equally

valient foe. It had advanced and retreated until the soldiers

were foot-sore from marching and counter-marching, crossing and

re-crossing the now historic streams of the Old Dominion. Of

all this, the loyal people were tired and demanded of the

Administration a change. The causes of the failures to take

the confederate capitol were not so much the fault of the commanders

of the brave army as that of the authorities at Washington, whose

indecision and interference had entailed almost a disgrace upon

McClellan, Hooker, Burnside and Meade.

But finally the people saw the greatest of the difficulties, and

demanded its removal, which the Administration signified its

willingness to do.

[Page 379]

Parade of the 20th Reg't. U. S. C. T. in New York

[Page 380] - BLANK PAGE

[Page 381]

Then began an activity at the

North, East and West, such as was never before witnessed. The

loyal heart was again aroused by the President's call for troops,

and all realized the necessity of a more sagacious policy, and the

importance of bringing the war to a close. The lion of the

South must be bearded in his lair, and forced to surrender Richmond,

the Confederate Capitol, that had already cost the Government

millions of dollars, and the North thousands of lives. The

cockade city, - Petersburg, - like the Gibralter of the Mississippi,

should haul down the confederate banner from her breastworks; in

fact, Lee must be vanquished. That was the demand of

the loyal nation, and right well did they enter into preparations to

consummate it; placing brave and skillful officers in command.

The whole North became a recruiting station.

Sumner, Greeley, Beeher, Philips and Curtis, with

the press had succeeded in placing the fight upon the highest plane

of civilization, and linked freedom to the cause of the Union

thus making the success of one the success of the other, - "Liberty

and Union, one and inseparable." What patriotism should fail

in accomplishing, bounties - National, State, county, city and

township - were to induce and effect. The depleted ranks of

the army were filled to its maximum, and with a hitherto victorious

and gallant leader would be hurled against the fortifications of the

Confederacy with new energy and determination.

Early in January, General Burnside

was ordered again to take command of the Ninth Army Corps, and

to recruit its strength to fifty thousand effective men, which he

immediately began to do. General Butler, then in

command of the Department of Virginia and North Carolina, began the

organization of the Army of the James, collecting at Norfolk,

Portsmouth and on the Peninsula, the forces scattered throughout his

Department, and to recruit Phalanx regiments. In March,

General Grant was called to Washington, and received the

appointment of Lieutenant General, and placed in command of

the armies.

[Page 382]

of the Republic. He

immediately began their reorganization, as a preliminary to

attacking Lee's veteran army of northern Virginia.

As has before been stated, the negro had, up to this

time, taken no very active part in the battles fought in Virginia.

The seed of prejudice sown by Generals McDowell and

McClellan at the beginning of hostilities, had ripened into

productive fruit. The Army of the Potomac being early engaged

in apprehending and returning run-away slaves to their presumed

owners, had imbibed a bitter, unrelenting hatred for the poor, but

ever loyal negro. To this bitterness the Emancipation

Proclamation gave a zest, through the pro-slavery press at the

North, which taunted the soldiers with "fighting to free the

negroes.' This feeling ha served to practically keep the

negro, as a soldier, out of the Army of the Potomac.

General Burnside, upon assuming his

command, asked for and obtained permission from the War Department

to raise and unite a division of Negro troops to the 9th Army Corps.

Annapolis, Md., was selected as the "depot and rendezvous," and very

soon Camp Stanton had received its allowance of Phalanx regiments

for the Corps. Early in April, the camp was broken, and the

line of march taken for Washington. It was rumored throughout

the city that the 9th Corps would pass through there, and that about

6,000 Phalanx men would be among the troops. The citizens were

on the qui vive; members of Congress and the President were

eager to witness the passage of the Corps.

At nine o'clock on the morning of the 25th of April,

the head of the column entered the city, and at eleven the troops

were marching down New York Avenue. Halting a short distance

from the corner of 14th street, the column closed up, and prepared

to pay the President a marching salute, who, with General

Burnside and a few friends, was awaiting their coming.

Mr. Lincoln and his party occupied a balcony over the entrance

of Williard Hotel. The scene was one of great beauty

and anima-

[Page 383]

tion. The day was superbly

clear; the soft atmosphere of the early spring was made additionally

pleasant by a cool breeze; rain had fallen the previous night,

and there was no dust to cause discomfort to the soldiers or

spectators. The troops marched and appeared well; their soiled

and battered flags bearing inscriptions of battles of six States.

The corps had achieved almost the first success of the war in North

Carolina; it had hastened to the Potomac in time to aid in rescuing

the Capitol, when Lee made his first Northern invasion; it

won glory at South Mountain, and made the narrow bridge at Antietam,

forever historic; it had likewise reached Kentucky in time to aid in

driving the confederates from that State. Now it appeared with

recruited ranks, and new regiments of as good blood as ever was

poured out in the cause of right; and with a new element - those

whom they had helped set free from the thraldom of slavery - whom

they were proud to claim as comrades.

Their banners were silent, effective witnesses of their

valor and their sacrifices; Bull's Run, Ball's Bluff, Roanoke,

Newburn, Gaines' Mills, Mechanicsville, Seven Pines, Savage Station,

Glendale, Malvern, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Antietam,

South Mountain, Knoxville, Vicksburg, Port Hudson and Gettysburg,

were emblazoned in letters of gold. The firm and soldierly

bearing of the veterans, the eager and expectant countenances of the

men and officers of the new regiments, the gay trappings of the

cavalry, the thorough equipment and fine condition of sabres, the

drum-beat, the bugle call, and the music of the bands were all

subjects of interest. The President beheld the scene.

Pavement, sidewalks, windows and roofs were crowded with people.

A division of veterans passed, saluting the President and their

commander with cheers. And then, with full ranks - platoons

extending from sidewalk to sidewalk - brigades which had never been

in battle, for the first time shouldered arms for their country;

they who even then were disfranchised and were not American

citizens, yet they were going out to

[Page 384]

fight for the flag. Their

country was given them by the tall, pale, benevolent hearted man

standing upon the balcony. For the first time, they beheld

their benefactor. They were darker hued than their veteran

comrades, but they cheered as lustily, "hurrah, hurrah, hurrah for

Massa Linkun! Three cheers for the President!"

They swung their caps, clapped their hands and shouted their joy.

Long, loud and jubilant were the rejoicings of these redeemed sons

of Africa. Regiment after regiment of stalwart men, - slaves

once, but freemen now, - with steady step and even ranks, passed

down the street, moving on to the Old Dominion. It was the

first review of the negro troops by the President. Mr.

Lincoln himself seemed greatly pleased, and acknowledged the

plaudits and cheers of teh Phalanx soldiers with a dignified

kindness and courtesy. It was a spectacle which made many eyes

grow moist, and left a life-long impression. Thus the corps

that had never lost a flag or a gun, marched through the National

Capitol, crossed long bridge and went into camp near Alexandria,

where it remained until the 4th of May.

The Phalanx regiments composing the 4th division were

the 19th, 23rd, 27th, 28th, 29th, 30th, 31st. 39th and 43rd,

commanded by General E. Ferrero.

The Army of the James, under

General Butler, which was to act in conjunction with the Army of

the Potomac, under Meade, was composed of the 10th and 18th

Corps. The 10th Corps had two brigades of the Phalanx,

consisting of the 7th, 9th, 29th, 16th, 8th, 41st, 45th and 127th

Regiments, commanded by Colonels James Shaw, Jr., and

Ulysses Doubleday, and constituted the 3rd division of that

Corps commanded by Brigadier-General Wm. Birney.

The 3rd division of the 18th Corps,

commanded by Brigadier-General Charles G. Paine, was

compolsed of the 1st, 22nd, 37th, 5th, 36th, 38th, 4th, 6th, 10th,

107th, 117th, 118th and 2nd Cavalry, with Colonels Elias Wright,

Alonzo G. Draper, John W. Ames and E. Martindale as

brigade commanders of the four brigades. A cav-

[Page 385]

alry force numbering about two

thousand, comprising the 1st and 2nd, was under command of

Colonel West, * making not less than 20,000 of the

Phalanx troops, including the 4th Division with the Ninth Corps, and

augmenting Butler's force to 47,000, concentrated at York

town and Gloucester Point.

On the 28th of April, Butler received his final

orders, and on the night of the 4th of May embarked his troops on

transports, descended the York river, passed Fortress Monroe and

ascended the James River. Convoyed by a fleet of armored war

vessels and gunboats, his transports reached Bermuda Hundreds on the

afternoon of the 5th. General Wilde, with a

brigade of the Phalanx, occupied Fort Powhatan, on the south bank of

the river, and Wilson's Wharf, about five miles below on the north

side of the James, with the remainder of his division of 5 000 of

the Phalanx. General Hinks landed at City Point, at

the mouth of the Appomattox. The next morning the troops

advanced to Trent's, with their left resting on the Appomattox, near

Walthall, and the right on the James, and intrenched. In the

meantime, Butler telegraphed Grant:

| |

|

'OFF CITY POINT, VA., May 5th. |

"LIEUT.

GEN. GRANT, Commanding Armies of the United States, Washington

D. C.

"We have seized Wilson's Wharf Landing; a brigade of

Wilde's colored troops are there; at Fort Powhatan landing two

regiments of the same brigade have landed. At City Point,

Hinks' division, with the remaining troops and battery,

have landed. The remainder of both the 18th and 10th Army

Corps are being landed at Bermuda Hundreds, above Appomattox.

No opposition experienced thus far, the movement was

comparatively a complete surprise. Both army corps left

York town during last night. The monitors are all over the

bar at Harrison's landing and above City Point. The

operations of the fleet have been conducted today with energy

and success. Gens. Smith and Gill

more are pushing the landing of the men. Gen.

Graham with the army gunboats, lead the advance during the

night, capturing the signal station of the rebels. Colonel

West, with 1800 cavalry, made several demonstrations from

Williamsburg yesterday morning. Gen. Rantz

left

---------------

*The reader will bear in mind that there were several

changes in the command of these troops during the campaign, on

account of promotions, but the troops remained in the Department and

Army of the James. See Roster, for changes.

[Page 386]

Suffolk this morning with his cavalry, for the

service indicated during the conference with the Lieut.-General.

The New York flag-of-truce boat was found lying at the wharf with

four hundred prisoners, whom she had not time to deliver. She

went up yesterday morning. We are landing troops during the

night, a hazardous service in the face of the enemy.

| "A. F. PUFFER,

Capt. and A. D. C. |

|

"BENJ. F. BUTLER,

Maj.-Gen. Commanding. |

About two

miles in front of their line ran the Richmond & Petersburg Railroad,

near which the enemy was encountered. Butler's

movements being in concert with that of the Army of the Potomac and

the 9th Corps, - the latter as yet an independent organization.

General Meade, with the Army of the Potomac,

numbering 120,000 effective men, crossed the Rapidan en route

for the Wilderness, each soldier carrying fifty rounds of ammunition

and three days rations. The supply trains were loaded with ten

days forage and subsistence. The advance was in two columns,

General Warren being on the right and General

Hancock on the left. Sedgwick followed closely upon

Warren and crossed the Rapidan at Germania Ford. The Ninth Corps

received its orders on the 4th, whereupon General Burnside

immediately put the Corps in motion toward the front.

Bivouacking at midnight, the line of march was again taken up at

daylight, and at night the Rapidan was crossed at Germania

Ford. The corps marched on a road parallel to that of its

old antagonist, General Longstreet's army, which was

hastening to assist Lee, who had met the Army of the Potomac

in the entanglements of the wilderness, where a stubborn and

sanguinary fight raged for two days. General

Ferrero's division, composed of the Phalanx regiments, reached

Germania Ford on the morning of the 6th, with the cavalry, and

reported to General Sedgwick, of the 6th Corps, who

had the care of the trains. The enemy was projecting an attack

upon the rear of the advancing columns. Gen. Ferrero

was ordered to guard with his Phalanx division, the bridges, roads

and trains near and at the Rapidan river. That night

the confederates attacked Sedgwick in force; wisely the

immense supply trains had been committed to the care of

[Page 387]

the Phalanx, and the enemy was

driven back before day light, while the trains were securely moved

up closer to the advance. General Grant, finding

that the confederates were not disposed to continue the battle,

began the movement toward Spottsylvania Court House on the night of

the 7th. The 9th Corps brought up the rear, with the Phalanx

division and cavalry covering the trains.

Butler and his Phalanx troops, as we have seen, was

within six miles of Petersburg, and on the 7th, Generals

Smith and Gillmore reached the railroad near Port

Walthall Junction, and commenced destroying it; the confederates

attacked them, but were repulsed. Col. West, on the

north side of the James River, forded the Chickahominy with the

Phalanx cavalry, and arrived opposite City Point, having destroyed

the railroad for some distance on that side.

Leaving General Hinks with his Phalanx

division to hold City Point, on the 9th Butler again moved forward

to break up the railroad which the forces under Smith and

Gillmore succeeded in doing, thus separating Beaurguard's

force from Lee's. He announced the result of his

operation's in the following message to Washington:

“Our operations may be summed up in a

few words. With one thousand and seven hundred cavalry we have

advanced up the Peninsula, forced the Chickahominy and have safely

brought them to our present position. These were colored

cavalry, and are now holding our advanced pickets toward Richmond.

General Kautz, with three thou sand cavalry from

Suffolk, on the same day with our movement up James river, forced

the Blackwater, burned the railroad bridge at Stony Creek, below

Petersburg, cutting in two Beauregard's force at that point.

We have landed here, intrenched ourselves, destroyed many miles of

railroad, and got possession, which, with proper supplies, we can

hold out against the whole of Lee's army. I have

ordered up the supplies. Beauregard, with a large

portion of his force, was left south, by the cutting of the railroad

by Kautz. That portion which reached Petersburg under

Hill, I have whipped to-day, killing and wounding many, and

taking many prisoners, after a well contested fight. General

Grant will not be troubled with any further re- inforcements

to Lee from Beaureguard's force.

| |

|

'BENJ. F. BUTLER,

Major-General" |

[Page 388]

But for

having been misinformed as to Lee's retreating on Richmond, -

which led him to draw his forces back into his intrenchments, -Butler

would have undoubtedly marched triumphantly into Petersburg: The

mistake gave the enemy holding the approaches to that city time to

be re-enforced, and Petersburg soon became well fortified and

garrisoned. Beaureguard succeeded in a few days time in

concentrating in front of Butler 25,000 troops, thus checking

the latter's advance toward Richmond and Petersburg, on the south

side of the James, though skirmishing went on at various points.

General Grant intended to have Butler

advance and capture Petersburg, while General Meade,

with the Army of the Potomac, advanced upon Richmond from the north

bank of the James river. Gen. Butler failed to

accomplish more than his dispatches related, though his forces

entered the city of Petersburg, captured Chester Station, and

destroyed the railroad connection between Petersburg and Richmond.

Failure to support his troops and to intrench lost him all he had

gained, and he re turned to his intrenchments at Bermuda

Hundreds. The Phalanx (Hinks division ) held City Point

and other stations on the river, occasionally skirmishing with the

enemy, who, ever mindful of the fact that City Point was the base of

supplies for the Army of the James, sought every opportunity to raid

it, but they always found the Phalanx ready and on the alert.

After the battle of Drewry's Bluff, May 16th,

Butler thought to remain quiet in his intrenchments, but

Grant, on the 22nd, ordered him to send all his troops,

save enough to hold City Point, to join the Army of the Potomac;

whereupon General W.F. Smith, with 16,000 men, embarked

for the White House, on the Pamunky river, Butler retaining

the Phalanx division and the Cavalry. Thus ended the

operations of the Army of the James, until Grant crossed the

river with the army of the Potomac.

On the 13th of May, Grant determined upon a

flank movement toward Bowling Green, with a view of making

[Page 389] - BLANK PAGE

[Page 390]

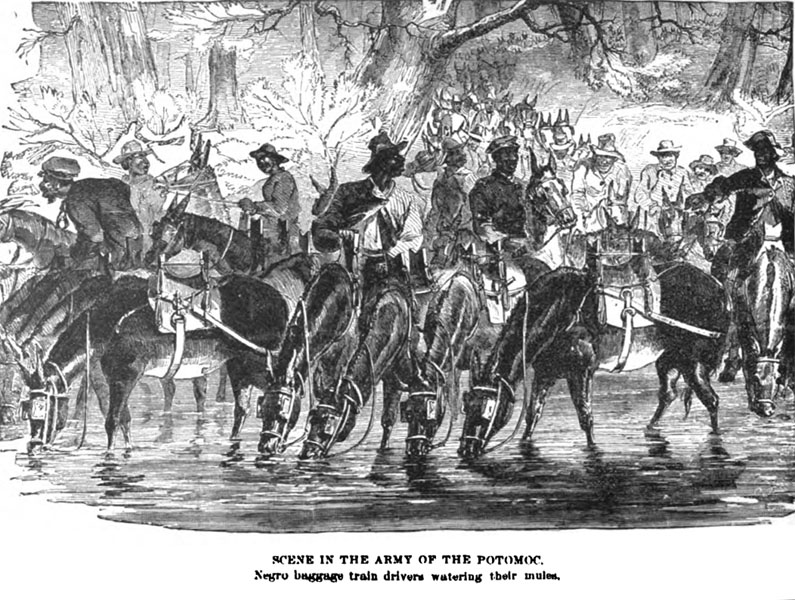

Scene in the Army of the Potomoc.

Negro baggage train drivers watering their mules

[Page 391]

Port Royal, instead of

Fredericksburg, his depot for supplies. Sending his reserve

artillery to Belle Plain, he prepared to advance. It was in

this manœuvre that Lee, for the last time, attacked the

Federal forces, outside of cover, in any important movement.

The attempt to change the base of supply was indeed a hazardous move

for Grant; it necessitated the moving of his immense train,

numbering four thousand wagons, used in carrying rations, ammunition

and supplies for his army, and transportation of the badly wounded

to the rear, where they could be cared for.

Up to this time the Wilderness campaign had been a

continuous fight and march. The anxiety which Grant

felt for his train, is perhaps best told by himself:

“ My movements are

terribly embarrassed by our immense wagon train. It could not

be avoided, however."

It was

the only means by which the army could obtain needful supplies, and

was consequently indispensable. It was the near approach to

the train that made the con federates often fight so desperately,

for they knew if they could succeed in capturing a wagon they would

probably get something to eat. Soon after the advance began,

it was reported to Grant, that the confederate cavalry was in

the rear, in search of the trains. On the 14th he ordered

General Ferrero to “keep a sharp lookout for this

cavalry, and if you can attack it with your (Phalanx) infantry and

(white ) cavalry, do so.” On the 19th Ferrero, with his

Phalanx division, (4th division, 9th Corps) was on the road to

Fredericksburg, in rear of and to the right of General

Tyler's forces, in the confederates' front. The road

formed Grant's direct communication with his base, and here

the confederates, under Ewell attacked the Federal troops. Grant

sent this dispatch to Ferrero:

“The enemy have crossed the Ny on the right of our lines, in

considerable force, and may possibly detach a force to move on

Fredericksburg. Keep your cavalry pickets well out on the

plank road, and all other roads leading west and south of you.

If you find the enemy moving infantry and artillery to you, report

it promptly. In that case take up strong positions and detain

him all you can, turning all your trains

[Page 392]

back to Fredericksburg, and whatever falling back

you may be forced to do, do it in that direction."

The

confederates made a dash for the train and captured twenty-seven

wagons, but before they had time to feast off of their booty the

Phalanx was upon them. The enemy fought with uncommon spirit;

it was the first time “F. F. V's," the chivalry of the South, -

composing the Army of Northern Virginia, - had met the negro

soldiers, and true to their instinctive hatred of their black

brothers, they gave them the best they had; lead poured like rain

for a while, and then came a lull. Ferrero knew what it

meant, and prepared for their coming. A moment more and the

accustomed yell rang out above the roar of the artillery. The

confederates charged down upon the Phalanx, but to no purpose, save

to make the black line more stable. They retaliated, and

the confederates were driven as the gale drives chaff, the Phalanx

recapturing the wagons and saving Grant's line of

communication. General Badeau, speaking of their

action, in his military history of Grant, says:

“It was the first time at the East when colored troops had been

engaged in any important battle, and the display of soldierly

qualities won a frank acknowledgment from both troops and

commanders, not all of whom had before been willing to look upon

negroes as comrades. But after that time, white soldiers in

the army of the Potomac were not displeased to receive the support

of black ones; they had found the support worth having."

Ferrero had the confidence of his men, who were ever ready

to follow where Grant ordered them to be led.

But this was not the last important battle the Phalanx

took part in. Butler, after sending the larger poition

of his forces to join the Army of the Potomac, was not permitted to

remain quiet in his intrenchments. The confederates felt

divined to destroy, if not capture, his base, and therefore were

continually striving to break through the lines. On the 24th

of May, General Fitzhugh Lee made a dash with

his cavalry upon Wilson's Wharf, Butler's most

northern outpost, held by two Phalanx Regiments of General

Wilde's brigade. Lee's men had been led to believe

that it was only necessary to yell at

[Page 393]

the "niggers” in order to make

them leave the Post, but in this affair they found a foe worthy of

their steel. They fought for several hours, when finally the

confederate troops beat a retreat. An eye witness of the fight

says:

“The chivalry of Fitzhugh Lee and his cavalry division

was badly worsted in the contest last Tuesday with negro troops,

composing the garrison at Wilson's Landing; the chivalry made

a gallant fight, how ever. The battle began at half-past

twelve P. M., and ended at six o'clock, when the chivalry retired,

disgusted and defeated. Lee's men dismounted far in the

rear, and fought as infantry; they drove in the pickets and

skirmishers to the intrenchments, and made several valiant charges

upon our works. To make an assault, it was necessary to come

across an opening in front of our position, up to the very edge of a

deep and impassable ravine. The rebels, with deafening yells,

made furious onsets, but the negroes did not flinch, and the

mad assailants, discomforted, returned to cover with shrunken

ranks. The rebels' fighting was very wicked; it showed that

Lee's heart was bent on taking the negroes at any cost.

Assaults on the center having failed, the rebels tried first

the left, and then the right flank, with no greater success.

When the battle was over, our loss footed up, one man killed

outright, twenty wounded, and two missing. Nineteen rebels

were prisoners in our hands. Lee's losses must have

been very heavy; the proof thereof was left on the ground.

Twenty-five rebel bodies lay in the woods unburied, and pools of

blood unmistakably told of other victims taken away. The

estimate, from all the evidence carefully considered, puts the

enemy's casualties at two hundred. Among the corpses Lee

left on the field, was that of Major Breckenridge, of

the 2nd Virginia Cavalry. There is no hesitation here in

acknowledging the soldierly qualities which the colored men engaged

in the fight have exhibited. Even the officers who have

hitherto felt no confidence in them are compelled to express

themselves mistaken. General Wilde, commanding

the Post, says that the troops stood up to their work like

veterans.”

Newspaper

correspondents were not apt to overstate the facts, nor to give too

much favorable coloring to the Phalanx in those days. Very

much of the sentiment in the army - East and West - was manufactured

by them. The Democratic partizan press at the North,

especially in New York and Ohio, still engaged in throwing paper

bullets at the negro soldiers, who were shooting lead bullets at the

country's foes.

The gallantry and heroic courage of the Phalanx in the

Departments of the Gulf and South, and their bloody sacrifices, had

not been sufficient to stop the violent

[Page 394]

clamor and assertions of those

journals, that the "niggers won't fight!”

Many papers favorable to the Emancipation, opposed

putting negro troops in battle in Virginia. But to all these

bomb-proof opinions Grant turned a deaf ear, and when and

where necessity required it, he hurled his Phalanx brigades against

the enemy as readily as he did the white troops. The conduct

of the former was, nevertheless, watched eagerly by the

correspondents of the press who were with the army, and when they

began to chronicle the achievements of the Phalanx, the prejudice

began to give way, and praises were substituted in the place of

their well-worn denunciations. A correspondent of the

New York Herald thus wrote in May:

“The conduct of the colored troops, by the way, in the actions of

the last few days, is described as superb. An Ohio soldier

said to me to day, “I never saw men fight with such desperate

gallantry as those negroes did. They advanced as grim and

stern as death, and when within reach of the enemy struck about them

with a pitiless vigor, that was almost fearful. 'Another

soldier said to me,' These negroes never shrink, nor hold

back, no matter what the order. Through scorching heat and

pelting storms, if the order comes, they march with prompt,

ready feet.' Such praise is great praise, and it is deserved.

The negroes here who have been slaves, are loyal, to a man,

and on our occupation of Fredericksburg, pointed out the prominent

secessionists, who were at once seized by our cavalry and put in

safe quarters. In a talk with a group of faithful fellows, I

discovered in them all a perfect understanding of the issues of the

conflict, and a grand determination to prove themselves worthy of

the place and privileges to which they are to be exalted."

The ice

was thus broken, and then each war correspondent found it his

duty to write in deservedly glowing terms of the Phalanx.

The newspaper reports of the engagements stirred the

blood of the Englishman, and he eschewed his professed love for the

freedom of mankind, and particularly that of the American negro.

The London Times, in the following article, lashed the North for

arming the negroes to shoot the confederates, forgetting, perhaps,

that England employed negroes against the colonist in 1775, and at

New Orleans, in 1814, had her black regiments to shoot down

[Page 395]

the fathers of the men whom it now

sought to uphold, in rebellion against the government of the United

States:

"THE NEGRO UNION SOLDIERS.

"Six months have now passed

from the time Mr. Lincoln issued his proclamation abolishing

slavery in the States of the Southern Confederacy. To many it

may seem that this measure has failed of the intended effect and

this is doubtless in some respects the case. It was intended

to frighten the Southern whites into submission, and it has only

made them more fierce and resolute than ever. It was intended

to raise a servile war, or produce such signs of it as should compel

the Confederates to lay down their arms through fear for their wives

and families; and it has only caused desertion from some of the

border plantations and some disorders along the coast. But in

other respects the consequences of this measure are becoming

important enough. The negro race has been too much attached to

the whites, or too ignorant or too sluggish to show any signs of

revolt in places remote from the presence of the federal armies; but

on some points where the federals have been able to maintain

themselves in force in the midst of a large negro population, the

process of enrolling and arming black regiments has been carried on

in a manner which must give a new character to the war. It is

in the State of Louisiana, and under the command of General

Banks, that this use of negro soldiers has been most

extensive. The great city of New Orleans having fallen into

the possession of the federals more more than a year ago, and the

neighboring country being to a certain degree abandoned by the white

population, a vast number of negroes have been thrown on the hands

of the General in command to support and, if he can, make use of.

The arming of these was begun by General Butler, and it has

been continued by his successor. Though the number actually

under arms is no doubt exaggerated by Northern writers, yet enough

have been brought into service to produce a powerful effect on the

imaginations of the the combatants, and, as we can now

clearly see, to add almost grievously to the fury of the struggle.

"Of all wars, those between races which had been

accustomed to stand to each other in the relation of master and

slave have been so much the most horrible that by general consent

the exciting of a servile insurrection has been considered as beyond

the pale of legitimate warfare. This had been held even in the

case of European serdom, although there the rulers and the ruled are

of the same blood, religion and language. But the conflict

between the white men and the negro, and particularly the

American white man and the American negro, is likely to be more

ruthless than any which the ancient world, fruitful in such

histories, or the modern records of Algeria can furnish.

There was reason to hope that the deeds of 1857 in India would not

be paralleled in our time or in any after age. The Asiatic

savagery rose upon a dominant race scattered throughout the land,

and wreaked its vengeance upon it by atrocities which it would be a

relief to forget. But it has

[Page 396]

been reserved for the New World to present the

spectacle of civil war, calling servile war to its aid, and of men

of English race and language 80 envenomed against each other that

one party places arms in the hands of the half savage negro, and the

other acts as if resolved to give no quarter to the insurgent race

or the white man who commands them or fights by their side. In

the valley of the Mississippi, where these negro soldiers are in

actual service, it seems likely that a story as revolting as that of

St. Domingo is being prepared for the world. No one who reads

the description of the fighting at Port Hudson, and the accounts

given by the papers of scenes at other places, can help fearing that

the worst part of this war has yet to come, and that a people who

lately boasted that they took the lead in education and material

civilization are now carrying on a contest without regard to any law

of conventional warfare, one side training negroes to fight against

its own white flesh and blood, the other slaughtering them without

mercy whenever they find them in the field.

" * * * It is

pitiable to find these unhappy Africans, whose clumsy frames are no

match for the sinewy and agile white American, thus led this manner,

it is possible that the massacre of Africans may not be confined to

actual conflict in the field. Hitherto the whites have been

sufficiently confident in the negroes to leave them unmolested,

even when the enemy was near; but with two or three black regiments

in each federal corps, and such events as the Port Hudson massacre

occuring to infuriate the minds on either side, who can

foresee what three months more of war may bring forth?

“All that we can say with certainty is that the unhappy

negro will be the chief sufferer in this unequal conflict. An

even greater calamity, however, is the brutalization of two

antagonistic peoples by the introduction into the war of these

servile allies of the federals. Already there are military

murders and executions on both sides. The horrors which Europe

has foreseen for a year past are now upon us. Reprisal will

provoke reprisal, until all men’s natures are hardened, and the land

flows with blood."

The

article is truly instructive to the present generation; its

malignity and misrepresentation of the Administration's intentions

in regard to the arming of negroes, serves to illustrate the

deep-seated animosity which then existed in England toward the union

of the States. Nor will the American negro ever forget

England's advice to the confederates, whose massacre of negro

soldiers fighting for freedom she endorsed and applauded. The

descendants of those black soldiers, who were engaged in the

prolonged struggle for freedom, can rejoice in the fact

[Page 397]

that no single act of those

patriots is in keeping with the Englishman's prediction; no taint of

brutality is even charged against them by those whom they took

prisoners in battle. The confederates themselves testify to

the humane treatment they unexpectedly received at the hands of

their negro captors. Mr. Pollard, the historian,

says:

“ No servile

insurrections had taken place in the South.”

But it is

gratifying to know that all Englishmen did not agree with the writer

of the Times. A London letter in the New York Evening Post,

said:

“Mr.

Spurgeon makes most effective and touching prayers,

remembering, at least once on a Sunday, the United States.

“Grant, O God,' he said recently, “that the right may conquer,

and that if the fearful canker of slavery must be cut out by the

sword, it be wholly eradicated from the body politic of which it is

the curse.' He is seldom, however, as pointed as this;

and, like other clergymen of England, prays for the return of

peace. Indeed, it must be acknowledged that if the English

press and government have done what they could to continue this war,

the dissenting clergy of England have nobly shown their good will

and hearty sympathy with the Americans, and their sincere desire for

the settlement of our difficulties. 'If praying would do you

Americans any good,' said an irreverent acquaintance last Sunday,

‘you will be gratified to learn that a force of a thousand -

clergymen-power is constantly at work for you over here.' "

After the

heroic and bloody effort at Cold Harbor to reach Richmond, or to

cross the James above the confederate capitol, and thus cut

off the enemy's supplies -after Grant had flanked, until to

flank again would be to leave Richmond in his rear, - when Lee

had withdrawn to his fortifications, refusing to accept Grant's

challenge to come out and fight a decisive battle, - when all hope

of accomplishing either of these objects had vanished, Grant

determined to return to his original plan of attack from the coast,

and turned his face toward the James river. On the 12th of

June the Army of the Potomac began to move, and by the 16th it was,

with all its trains across, and on the south side of the James.

Petersburg Grant regarded as the citadel

of Richmond, and to capture it was the first thing on his list to be

accomplished. General Butler was made acquainted

[Page 398]

with this, and as soon as

General Smith, who, with a portion of Butler's

forces had been temporarily dispatched to join the army of the

Potomac at Cold Harbor, returned to Bermuda Hundreds with his force,

he was ordered forward to capture the Cockade City. It was

midnight on the 14th, when Smith's troops arrived.

Butler ordered him immediately forward against Petersburg, and

he moved accordingly. His force was in three divisions of

Infantry, and one of Cavalry, under General Kautz, who

was to threaten the line of works on the Norfolk road.

General Hinks, with his division of the Phalanx, was to

take position across the Jordon's Point road on the right of

Kautz; Brooks' division of white troops was to follow,

Hinks coming in at the center of the line, while General

Martindale with the other division was to move along the

Appomattox and strike the City Point road. Smith's

movement was directed against the north east side of Petersburg,

extending from the City Point to the Norfolk railroad. About

daylight on the 15th, as the columns advanced on the City Point road

at Bailey's farm, six miles from Petersburg, a

confederate battery opened fire. Kautz reconnoitered

and found a line of rifle trench, extending along the front, on

rapidly rising ground, with a thicket covering. The work was

held by a regiment of cavalry and a light battery. At once

there was use for the Phalanx; the works must be captured with the

battery before the troops could proceed. The cavalry was

re-called, and Hinks began the formation of an attacking

party from his division. The confederates were in an open

field, their battery upon a knoll in the same field, commanding a

sweeping position to its approaches. The advancing troops must

come out from the woods, rush up the slope and carry it at the point

of the bayonet, exposed to the tempest of musketry and cannister of

the battery. Hinks formed his line for the assault, and

the word of command was given, - "forward." The line emerged

from the woods, the enemy opened with cannister upon the steadily

advancing column, which, without stopping, replied with a volley of

Minie bullets.

"The long, dusky line,

arm to arm, knee to knee.”

[Page 399] - BLANK PAGE

[Page 400]

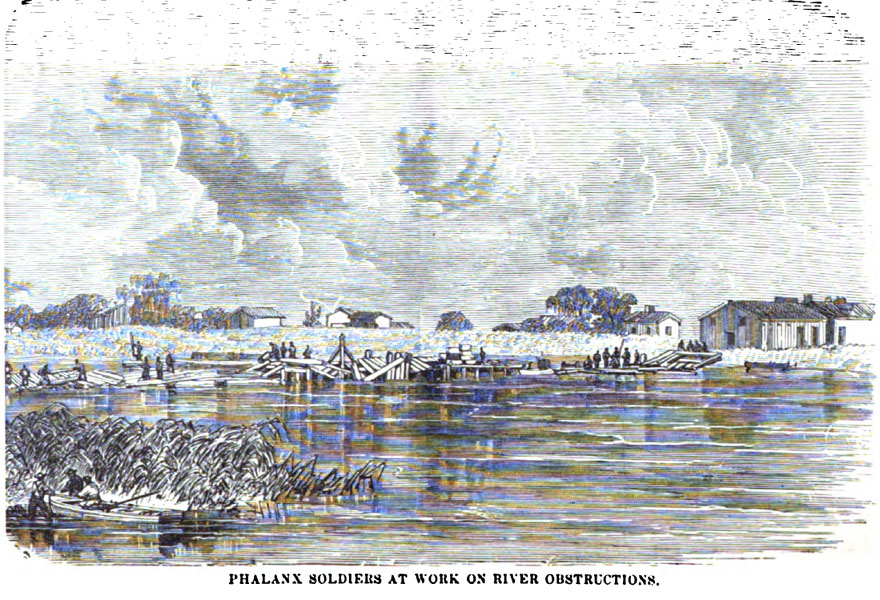

Phalanx Soldiers at Work on river Obstructions

[Page 401]

Then

shells came crashing through the line, dealing death and shattering

the ranks; but on they went, with a wild cheer, running up the

slope; again a storm of cannister met them; a shower of musketry

came down upon the advancing column, whose bristling bayonets were

to make the way clear for their white comrades awaiting on the

roadside. A hundred black men went down under the fire; the

ranks were quickly closed however, and with another wild cheer the

living hundreds went over the works with the impetuosity of a

cyclone; they seized the cannon and turned them upon the fleeing

foe, who, in consternation, stampeded toward Petersburg, to their

main line of intrenchments on the east. Thus the work of the

5th and 22nd Phalanx regiments was completed and the road made clear

for the 18th Corps.

Brooks now moved up simultaneously with

Martindale, on the river road. By noon the whole corps was

in front of the enemy's main line of works, Martindale on the

right, Brooks in the center, the Phalanx and cavalry on the

left, sweeping down to the Jerusalem Plank Road on the southeast.

Hinks, with the Phalanx, in order to gain the position

assigned him, had necessarily to pass over an open space exposed to

a direct and cross-fire. Nevertheless, he prepared to occupy

his post, and forming a line of battle, he began the march.

The division numbered about 3,000, a portion of it being still at

Wilson's Landing, Fort Powhatan, City Point and Bermuda

Hundreds. This was a march that veterans might falter in,

without criticism or censure. The steady black line advanced a

few rods at a time, when coming within range of the confederate guns

they were obliged to lie down and wait for another opportunity.

Now a lull, - they would rise, go forward, and again lie down.

Thus they continued their march, under a most galling, concentrated

artillery fire until they reached their position, from which they

were to join in a general assault; and here they lay, from one till

five o'clock, - four long hours, - exposed to cease less shelling by

the enemy. Badeau says, in speaking of the Phalanx in

this ordeal:

[Page 402]

“No worse strain on the

nerves of troops is possible, for it is harder to remain quiet under

cannon fire, even though comparatively harm less, than to advance

against a storm of musketry.”

General W. F. Smith, though brave, was too cautious and

particular in detail, and he spent those four hours in careful

reconnoissance, while the troops lay exposed to the enemy's

concentric fire.

The main road leading east from Petersburg ascends a

hill two or more miles out, upon the top of which stood what was

then known as Mr. Dunn's house. In front of it

was a fort, and another south, and a third north, with other works;

heavy embankments and deep ravines and ditches, trunks of hewn trees

blackened by camp fires, formed an abatis on the even ground.

Here the sharp shooters and riflemen had a fair view of the entire

field. The distance from these works to the woods was about

three hundred and sixty paces, in the edge of which lay the black

Phalanx division, ready, like so many tigers, waiting for the

command, “forward.” The forts near Dunn's house

had direct front fire, and those on the north an enfilading fire on

the line of advance. Smith got his troops in line for

battle by one o'clock, but there they lay.

Hinks impatiently awaited orders; oh! what a

suspense - each hour seemed a day, - what endurance - what valor.

Shells from the batteries ploughed into the earth where they stood,

and began making trouble for the troops. Hinks gave the

order, “lie down;" they obeyed, and were somewhat sheltered.

Five o'clock - yet no orders. At length the command was given,

“forward.” The skirmishers started at quick time; the enemy

opened upon them vigorously from their batteries and breastworks,

upon which they rested their muskets, in order to fire with

accuracy. A torrent of bullets was poured upon the advancing

line, and the men fell fast as autumn leaves in a gale of wind.

Then the whole line advanced, the Phalanx going at double-quick;

their well aligned ranks, with bayonets glittering obliquely in the

receding sunlight, presented a spectacle both magnificent and grand.

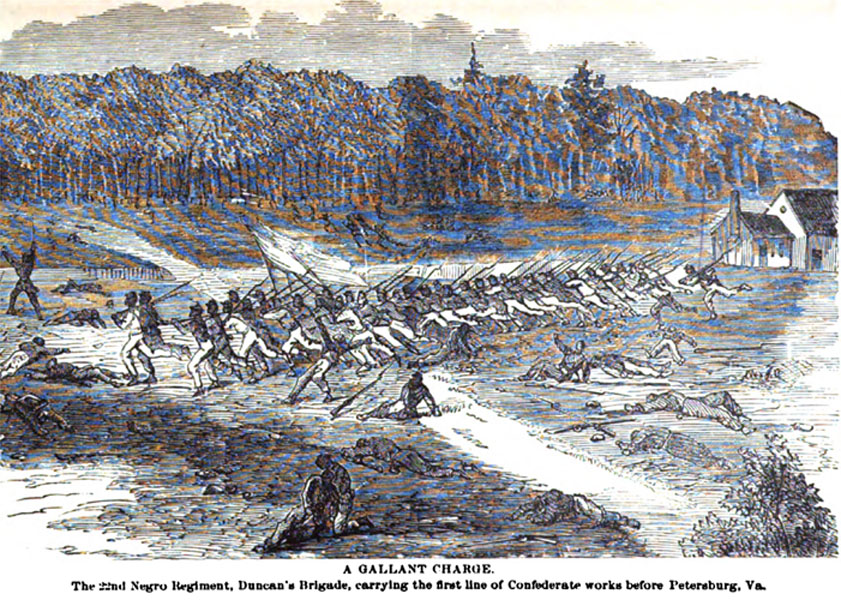

Duncan rushed his skirmishers and reached the

ditches in front of the breastworks, which, without waiting for

[Page 403]

A Gallant Charge

The 22nd Negro Regiment, Duncan's Brigade, carrying the first line

of Confederate works before Petersburg, Va.

[Page 404] - BLANK PAGE

[Page 405]

the main body, they entered and

clambered up the steep embankments. A sheet of flame from

above was rained down, causing many a brave man to stagger and fall

back into the ditch, never to rise again. The troops

following, inspired by the daring of the skirmishers, pressed

forward on the run up to the forts, swept round the curtains, scaled

the breastworks and dashed with patriotic rage at the confederate

gunners, who deserted their pieces and ran for their lives.

Brooks and Martindale advanced simultaneously upon the

works at Osborn's house and up the railroad, sweeping

everything before them. The Phalanx seized upon the guns and

turned them instantly lanx seized upon the

guns and turned them instantly upon the fleeing foe, and then with

spades and shovels reversed the fortifications and prepared to hold

them. Fifteen pieces of artillery and three hundred

confederates were captured. “The Phalanx,” says the official report,

took two-thirds of the prisoners and nine pieces of artillery. General

Smith, finding that General Birney, with the

2nd Corps, had not arrived, instead of marching the troops into

Petersburg, waited for re-inforcements unnecessarily, and thereby

lost his chance of taking the city, which was soon garrisoned with

troops enough to defy the whole army. Thus Grant was

necessitated afterward to lay seige to the place.

The confederates never forgot nor forgave this daring

of the "niggers," who drove them, at the point of the bayonet, out

of their breastworks, killing and capturing their comrades and their

guns. They were chided by their brother confederates for

allowing negroes to take their works from them. The maidens of

the Cockade City were told that they could not trust themselves to

men who surrendered their guns to "niggers.” The soldiers of

the Phalanx were delirious with joy. They had caught “ole

massa," and he was theirs. General Hinks had

their confidence, and they were ready to follow wherever he led.

The chaplin of the 9th Corps, in his history, says:

[Page 406]

one piece of artillery in the most gallant

manner. On their arrival before Petersburg, they lay in front

of the works for nearly five hours, waiting for the word of command.

They then, in company with the white troops, and showing equal

bravery, rushed and carried the enemy's line of works, with what

glorious success has already been related.”

This,

indeed, was a victory, yet shorn of its full fruits; but t

hat Petersburg was not captured was no fault of the Phalanx.

They had carried and occupied the most formidable obstacles

Badeau, in chronicling these achievements, says:

“General Smith

assaulted the works on the City Point and Prince George Court House

roads. The rebels resisted with a sharp infantry fire,

but the center and left dashed into the works, consisting of five

redan's on the crest of a deep and difficult ravine. Kiddoo's

(220) black regiment was one of the first to gain the hill. In

support of this movement, the second line was swung around and moved

against the front of the remaining works. The rebels,

assaulted thus in front and flank, gave way, tour of the guns

already captured were turned upon them by the negro conquerors,

enfilading the line, and before dark, Smith was in possession

of the whole of the outer works, two and a half miles long, with

fifteen pieces of artillery and three hundred prisoners.

Petersburg was at his mercy.”

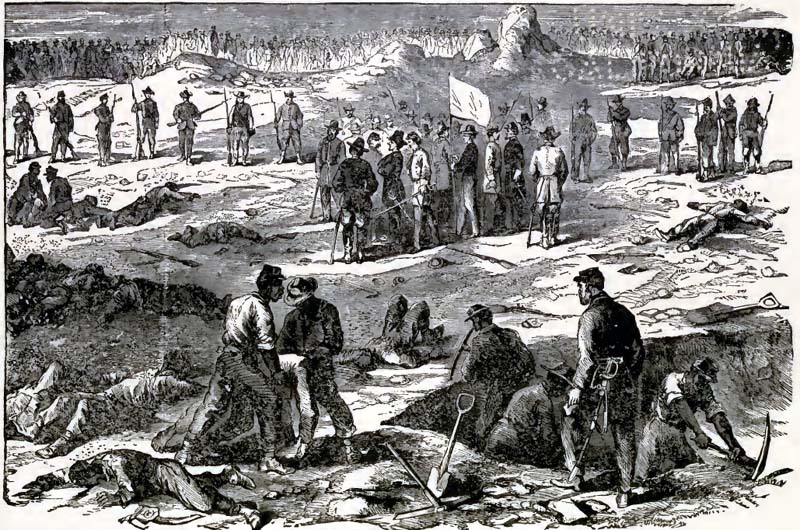

This

failure made a siege necessary, and General Grant

began by regular approaches to invest the place, after making the

three desperate assaults on the 16th, 17th and 18th. It had

been indeed a bloody June; the soil of the Old Dominion, which for

two centuries the negro had tilled and made to yield the choicest

products, under a system of cruel and inhuman bondage he now

reddened with his blood in defense of his liberty, proving by his

patriotism, not only his love of liberty, but his courage and

capacity to defend it. The negro troops had marched and fought

with the white regiments with equal intrepidity and courage; they

were no longer despised by their comrades; they now had recognition

as soldiers, and went into the trenches before Petersburg as a part

of as grand an army as ever laid siege to a stronghold or stormed a

fortification.

On the 18th of June, General Ferrero

reported to General Meade, with his division of the

Phalanx, (4th

[Page 407]

Division, 9th Corps), and was

immediately ordered to join its own proper corps, - from which it

had been separated since the 6th of May, - at the crossing of the

Rapidan. It had served under Sedgwick and Sheridan

until the 17th, when it came under the direct command of General

Grant, and thus remained until the 25th of May, when

General Burnside, waiving rank to Meade, the 9th

Corps was incorporated into the Army of the Potomac. During

its absence the division sustained the reputable renown of its

corps, not only in protecting the trains, but in fighting the enemy,

and capturing prisoners. Before rejoining the corps, the

division was strengthened by three regiments of cavalry, - the

5th New York, 3rd New Jersey and 2nd Ohio. From the 9th of May

till the 17th, the division occupied the plank road,

looking to the old Wilderness tavern, covering the extreme right of

the army, extending from Todd's to Banks' Ford.

On the 17th, the division moved to Salem Church, near the main

road to Fredericksburg, where, as we have seen, it defended the rear

line against the attack made by the con federates, under General

Ewell.

The historian of the corps says:

“The division on the

21st of May was covering Fredericksburg, and the roads leading hence

to Bowling Green. On the 22nd it marched toward Bowling Green,

and on the 23rd it moved to Milford Station. From that date to

the 27th it protected the trains of the army in the rear of the

positions on the North Anna. On the 27th, the division

moved to Newtown; on the 28th, to Dunkirk, crossing the Maltapony;

on the 29th, to the Pamunkey, near Hanovertown. On the

1st of June the troops crossed the Pamunkey, and from the 2nd to the

6th, covered the right of the army; from the 6th to the 12th they

covered the approaches from New Castle Ferry, Hanovertown, Hawe's

shop, and Bethusda Church. From the 12th to the 18th they

moved by easy stages, by way of Tunstall's New Kent Court House,

Cole's Ferry, and the pontoon bridge across the James, to the line

of the army near Petersburg. The dismounted cavalry were left

to guard the trains, and the 4th Division prepared to participate in

the more active work of soldiers. Through the remainder of the

month of June, and the most of July, the troops were occupied in the

second line of trenches, and in active movements towards the left,

under Generals Hancock and Warren. While

they were engaged in the trenches they were also drilled in the

movements necessary for an attack and occupation of the enemy's

[Page 408]

the hearts of the blacks, and they began to think

that they too might soon have the opportunity of some glory for

their race and country.”

How

natural was this feeling. As we have seen, their life

for more than a month had been one of marching and counter-marching,

though hazardous and patriotic. When on the 18th, they

entered upon the more active duty of soldiers, they found the 3rd

Division of the 18th Corps, composed of the Phalanx of the Army of

the James, covered with glory, and the welkin ringing with praises

of their recent achievements. The men of the 4th Division

chafed with eager ambition to rival their brothers of the 18th

Corps, in driving the enemy from the Cockade City. General

Burnside was equally as anxious to give his black boys a

chance to try the steel of the chivalry in deadly conflict, and this

gave them consolation, with the assurance that their day would ere

long dawn, so they toiled and drilled carefully for their

prospective glory.

But the situation of the Phalanx

before Petersburg was far from being enviable. Smarting

under the thrashing they had received from Hinks' division,

the confederates were ever ready now to slaughter the “niggers" when

advantage offered them the opportunity. A steady, incessant

fire was kept up against the positions the Phalanx occupied, and

their movements were watched with great vigilance.

Although they did not raise the black flag, yet manifestly no

quarter to negro troops, or to white troops that fought with them,

was the confederates' determination.

“Judging from their

actions, the presence of the negro soldiers, both in the Eighteenth

and Ninth Corps," says Woodbury, "seemed to have the effect of

rendering the enemy more spiteful than ever before the Fourth

Division came. The closeness of the lines on the front of the

corps rendered constant watchfulness imperative, and no day passed

without some skirmishing between the opposing pickets. When

the colored soldiers appeared, this practice seemed to

increase, while in front of the Fifth Corps, upon the left of our

line, there was little or no picket firing, and the outposts of both

armies were even disposed to be friendly. On the front of the

Ninth, the firing was incessant, and in many cases fatal.”

[Page 409] - BLANK PAGE

[Page 410]

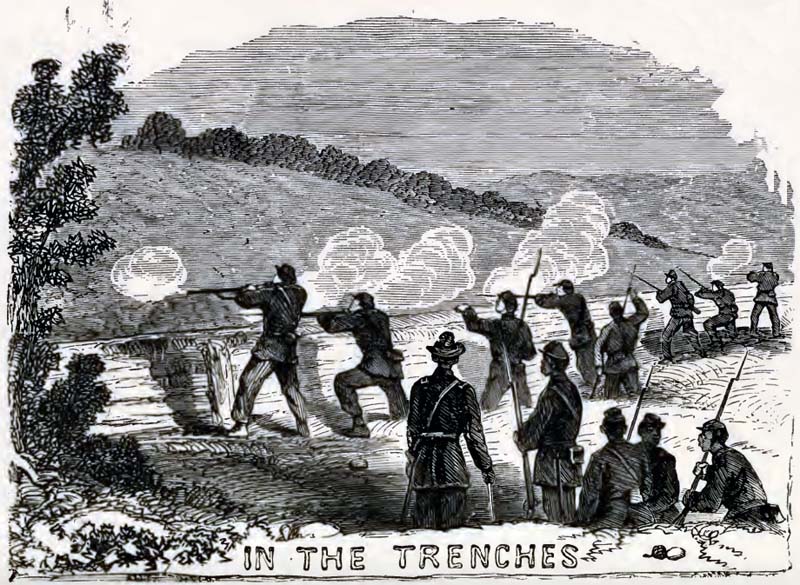

In the Trenches

[Page 411]

“General

Potter, in his report, mentions that, when his division occupied

the front, his loss averaged some fourteen or fifteen officers

killed and wounded per diem. The sharpshooters on either side

were vigilant, and an exposure of any part of the person was the

signal for the exchange of shots. The men, worn by hard

marching, hard fighting and bard digging, took every precaution to

shield themselves, and sought cover at every opportunity. They

made fire proofs of logs and earth, and with tortuous covered ways

and traverse, endeavoring to secure themselves from the enemy's

fire. The artillery and mortars on both sides were kept almost

constantly at work. These were all precursors of the coming,

sanguinary struggle for the possession of Cemetery Hill.

Immediately in front of the salient occupied by the Ninth Corps, the

rebels had constructed a very strong redoubt, a short distance below

Cemetery Hill. In the rear of the redoubt ran a ridge nearly

at right angles with the rebels' lines, to the hill. It

appeared that if this redoubt was captured, the enemy's line would

be seriously threatened, if not entirely broken up. A feasible

plan for the destruction of the redoubt, was seriously discussed

among the soldiers destruction of the redoubt, was seriously

discussed among the soldiers of the corps; finally Colonel

Pleasants, of the 48th Pennsylvania Regiment, devised a plan to

run a mine under the intervening space between the line of the corps

and the redoubt, with the design of exploding it, directly under the

redoubt. To this plan General Burnside lent his

aid, and preparations were made for an assault upon Cemetery Hill,

at the time of its explosion. The work of digging and

preparing the mine was prosecuted under the most disadvantageous

circumstances. General Meade reluctantly gave

official sanction, and the work of excavation proceeded with,

despite the fact that General Burnside's requisitions

for supplies were not responded to. Nevertheless, in less than

a month the mine was ready, and after considerable discussion, and

not without some bickering, the plan of attack was arranged, which,

in brief, was to form two columns, and to charge with them through

the breach caused by the explosion of the mine. Then to sweep

along the enemy's line, right and left, clearing away the artillery

and infantry, by attacking in the flank and rear. Other

columns were to make for the crest, the whole to co-operate.

General Ferrero, in command of the Phalanx division

was informed, that in accordance with the plan of attack, he was to

lead in the assault, when the attack was made, after the mine had

been fired. He was ordered to drill his troops accordingly.

After a careful examination of the ground, Ferrero decided

upon his methods of advance, not to go directly in the crater formed

by the explosion, but rather upon one side of it, and then to take

the enemy in flank and reverse. When he informed his officers

and men that they would be called upon to lead in the assault, they

received the information with delight. His men, desirous of

emulating their comrades of the Third Division of the Eighteenth

Corps, felt that their cherished hope, the opportunity for which

they had prayed, - was near at hand; the hour in which they would

show themselves worthy of the honor of being asso-

[Page 412]

ciated with the Army of the Potomac. They

rejoiced at the prospect of wiping off whatever reproach an

ill-judged prejudice might have cast upon them, by proving

themselves brave, thereby demanding the respect which brave men

deserve. For three weeks they drilled with alacrity in the

various movements; charging upon earthworks, wheeling by the right

and left, deployment, and other details of the expected operations.

General Burnside had early expressed his confidence in the

soldierly capabilities of the men of the Phalanx, and now wished to

give them an opportunity to justify his good opinion.”

His white

troops, moreover, had been greatly exposed throughout the whole

campaign, had suffered severely, and had been so much under the fire

of the sharpshooters that it had become a second nature with them to

dodge bullets. The negro troops had not been so much exposed,

and had already shown their steadiness under fire in one or two

pretty severe skirmishes in which they had previously been engaged.

The white officers and men of the corps were elated with the

selection made by General Burnside, and they, too,

manifested an uncommon interest in their dark-hued comrades.

The demeanor of the former toward the latter was very different from

that of the other corps, of which that particular army was composed.

The 9th Corps had seen more service than any other corps in the Army

of the Potomac. Its operations in six States had given to the

men an experience calculated to destroy, very greatly, their race

prejudice; besides a very large portion of the regiments in the

corps came from the New England States, especially Massachusetts,

Vermont and Rhode Island, where race prejudice was not so strong;

consequently the treatment of the men in the 4th Division was

tempered by humanity, and pregnant with a fraternal feeling of

comradeship. And then there was a corps pride very naturally

existing among the white troops, which prompted a desire for the

achievement of some great and brilliant feat by their black

comrades. This feeling was expressed in more than one way by

the entire corps, and greatly enhanced the ambition of the Phalanx

to rout the enemy and drive him out of his fortifications before

Petersburg, if not to capture the city.

These high hopes were soon dissipated, however, Gen-

[Page 413]

eral Meade had

an interview with General Burnside on the 28th; the

subject was fully discussed as to the plan of the assault, as

proposed by General Burnside, and made known to

Meade by Burnside, in writing, on the 26th. It was

at this meeting that General Meade made his objections

to the Phalanx leading the assault. General Burn

side argued with all the reason he could command, in favor of his

plans, and especially for the Phalanx, going over the grounds

already cited; why his white troops were unfit and disqualified for

performing the task of leading the assault, but in vain. Meade

was firm in his purpose, and, true to his training, he had no use

for the negro but as a servant; he never had trusted him as a

soldier. The plan, with General Meade's

objection was referred to General Grant for

settlement. Grant, doubting the propriety of agreeing with a

subordinate, as against the commander of the army, dismissed the

dispute by agreeing with Meade; therefore the Phalanx was

ruled out of the lead and placed in the supporting column.

It was not till the night of the 29th, a few hours before the

assault was made, that the change was made known to General

Ferrero and his men, who were greatly chagrined and filled

with disappointment.

General Ledlie's division of white troops

was to lead the assault, after the explosion of the mine on the

morning of the 30th. It was on the night of the 29th, when

General Burnside issued his battle order, in accordance

with General Meade's plan and instructions, and at the

appointed hour all the troops were in readiness for the conflict.

The mine, with its several tons of powder, was ready at a quarter

past three o'clock on the eventful morning of the 30th of July.

The fuses were fired, and “all eyes were turned to the confederate

fort opposite," which was discernible but three hundred feet

distant. The garrison was sleeping in fancied security; the

sentinels slowly paced their rounds, without a suspicion of the

crust which lay between them and the awful chasm below. Our own

troops, lying upon their arms in unbroken silence, or with an

occasional murmur, stilled at once by

[Page 414]

the whispered word of command, looked

for the eventful moment of attack to arrive. A quarter of an

hour passed, -a half hour, yet there was no report. Four

o'clock, and the sky began to brighten in the east; the confederate

garrison was bestirring itself. The enemy's lines once more

assumed the appearance of life; the sharp shooters, prepared for

their victims, began to pick off those of our men, who came within

range of their deadly aim. Another day of siege was drawing

on, and still there was no explosion. What could it mean?

The fuses had failed, -the dampness having penetrated to the place

where the parts had been spliced together, prevented the powder from

burning. Two men (Lieut. Jacob Douty and

Sergeant - afterwards Lieutenant Henry Rees,)

of the 48th Pennsylvania volunteered to go and ascertain where the

trouble was. At quarter past four o'clock they bravely entered

the mine, re-arranged the fuses and re lighted them. In the

meantime, General Meade had arrived at the permanent

headquarters of the 9th Corps. Not being able to

see anything that was going forward, and not hearing any report, he

became somewhat impatient. At fifteen minutes past four

o'clock he telegraphed to General Burnside to know

what was the cause of the delay. Gen. Burnside was too

busy in remedying the failure already incurred to reply immediately,

and expected, indeed, that before a dispatch could be sent that the

explosion would take place. General Meade

ill-naturedly telegraphed the operator to know where General

Burnside was. At half-past four, the commanding general

became still more impatient, and was on the point of ordering an

immediate assault upon the enemy's works, without reference to the

mine. Five minutes later he did order an assault.

General Grant was there when, at sixteen minutes

before five o'clock, the mine exploded. Then ensued a scene

which beggars description.

General Badeau, in describing the

spectacle, says:

“The

mine exploded with a shock like that of an earthquake, tearing up

the rebels' work above them, and vomiting men, guns and cais-

[Page 415]

sons two hundred feet into the air. The

tremendous mass appeared for a moment to hang suspended in the

heavens like a huge, inverted cone, the exploding powder still

flashing out here and there, while limbs and bodies of mutilated

men, and fragments of cannon and wood-work could be seen, then all

fell heavily to the ground again, with a second report like thunder.

When the smoke and dust had cleared away, only an enormous crater,

thirty feet deep, sixty wide, and a hundred and fifty long stretched

out in front of the Ninth Corps, where the rebel fort had been."

The

explosion was the signal for the federal batteries to open fire, and

immediately one hundred and ten guns and fifty mortars opened along

the Union front, lending to the sublime horror of the upheaved and

quaking earth, the terror of destruction.

A confederate soldier thus describes the explosion, in

the Philadelphia Times, January, 1883:

“About fifteen feet of dirt intervened between the sleeping soldiers

and all this powder. In a moment the superincumbent earth, for

a space forty by eighty feet, was hurled upward, carrying with it

the artillerymen, with their four guns, and three companies of

soldiers. As the huge mass fell backwards it buried the

startled men under immense clods - tons of dirt. Some of the

artillery was thrown forty yards towards the enemy's line. The

clay subsoil was broken and piled in large pieces, often several

yards in diameter, which afterwards protected scores of Federals

when surrounded in the crater. The early hour, the unexpected

explosion, the concentrated fire of the enemy's batteries, startled

and wrought confusion among brave men accustomed to battle."

Says a Union

account:

“Now

was the time for action, forward went General Ledlie's

column, with Colonel Marshall's brigade in advance.

The parapets were surmounted, the abatis was quickly removed, and

the division prepared to pass over the intervening ground, and

charge through the still smoking ruins to gain the crest beyond.

But here the leading brigade made a temporary halt; it was said at

the time our men suspected a counter mine, and were themselves

shocked by the terrible scene they had witnessed. It was,

however, but momentary; in less than a quarter of an hour, the

entire division was out of its entrenchments, and was advancing

gallantly towards the enemy's line. The ground was somewhat

difficult to cross over, but the troops pushed steadily on with

soldiery bearing, overcoming all the obstacles before them.

They reached the edge of the crater, passed down into the chasm and

attempted to make their way through the yielding sand, the bro-

[Page 416]

ken clay, and the masses of rubbish that were

everywhere about. Many of the enemy's men were lying among the

ruins, half buried, and vainly trying to free themselves. They

called for mercy and for help. The soldiers stopped to take

prisoners, to dig out guns and other material. Their

division commander was not with them, there was no responsible head,

the ranks were broken, the regimental organizations could not be

preserved, and the troops were becoming confused. The enemy

was recovering from his surprise, our artillery began to receive a

spirited response, the enemy's men went back to their guns; they

gathered on the crest and soon brought to bear upon our troops a

fire in front from the Cemetery Hill, and an enfilading and

cross-fire from their guns in battery. Our own guns could not

altogether silence or overcome this fire in flank, our men in the

crater were checked, felt the enemy's fire, sought cover, began to

entrench. The day was lost, still heroic men continued to push

forward for the crest, but in passing through the crater few got

beyond it. Regiment after regiment, brigade followed brigade,

until the three white divisions filled the opening and choked the

passage to all. What was a few moments ago organization and

order, was now a disordered mass of armed men. At six o'clock,

General Meade ordered General Burnside

to push his men forward, at all hazards, white and black. His

white troops were all in the crater, and could not get out. As

instructed, he ordered General Ferrero to rush in the

Phalanx; Colonel Loving was near when the order came

to Ferrero; as the senior staff officer present, seeing the

impossibility of the troops to get through the crater, at that time

countermanded the order, and reported in person to General

Burnside, but he had no discretion to exercise, his duty was

simply to repeat Meade's order. The order must be

obeyed; it was repeated; away went the Phalanx division, loudly

cheering, but to what purpose did they advance? The historian

of that valiant corps, presumably more reliable than any other

writer, says:

“The colored troops charged forward, cheering with

enthusiasm and gallantry. Colonel J. K. Sigfried, commanding

the first brigade, led the attacking column. The command moved

out in rear of Colonel Humphrey's brigade of the Third

Division. Colonel Sigfried, passing Colonel

Humphrey by the flank, crossed the field immediately in

front, went down the crater, and attempted to go through. The

passage was exceedingly difficult, but after great exertions the

brigade made its way through the crowded masses in a somewhat broken

and disorganized condition, and advanced towards the crest.

The 43rd U.S. Colored troops moved over the lip of the crater toward

the right, made an attack upon the enemy's line of intrenchments,

and won the chief success of the day, capturing a number of

prisoners and rebel colors, and re-capturing a stand of national

colors. The other regiments of the brigade were unable to get

up, on account of white troops in advance of them crowding the line.

The second brigade, under command of Colonel H. G. Thomas,

followed the first with equal enthusiasm. The

[Page 417]

through. Colonel Thomas'

intention was to go to the right and attack the enemy's rifle-pits.

- He partially succeeded in doing so, but his brig ade was much

broken up when it came under the enemy's fire. The gallant

brigade commander endeavored, in person, to rally his command, and

at last formed a storming column, of portions of the 29th, 28th,

23rd, and 19th Regiments of the Phalanx division.'

" 'These troops' made a spirited attack, but lost

heavily in officers and became somewhat disheartened.

Lieutenant-Colonel Bross, of the 29th, with the colors in his

hands, led the charge; was the first man top leap upon the nemy's

works, and was instantly killed. Lieutenant Pennell

seized the colors, but was shot down, riddled through and through.

Major Theodore H. Rockwood, of the 19th, sprang upon the

parapet, and fell while cheering on his regiment to the attack.

The conduct of these officers and their associates was indeed

magnificent. No troops were ever better lead to an assault;

had they been allowed the advance at the outset, before the enemy