|

CHAPTER II.

-

ORIGIN AND GROWTH OF THE

UNDERGROUND ROAD

Pg. 17 - 46

THE Underground Road

developed in a section of country rid of slavery, and

situated between two regions, from one of which slaves

were continually escaping with the prospect of becoming

indisputably free on crossing the borders of the other.

Not a few persons living within the intervening

territory were deeply opposed to slavery, and although

they were bound by law to discountenance slaves seeking

freedom, they felt themselves to be more strongly bound

by conscience to give them help. Thus it happened

that in the course of the sixty years before the

outbreak of the War of the Rebellion the Northern states

became traversed by numerous secret pathways leading

from Southern bondage to Canadian liberty.

Slavery was put in process of extinction at an early

period in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York and the New

England states. From the five and a fraction

states created out of the Northwestern Territory slavery

was excluded by the Ordinance of 1787. It is

interesting to note how rapid was the progress of

emancipation in the Northeastern states, where the

conditions of climate, and industry and public opinion

were unfavorable to the continuance of slavery. In

1777 emancipation was begun by the action of Vermont,

which upon its separation from New York adopted a

constitution in which slavery was prohibited.

Pennsylvania and Massachusetts was less direct, but not

less effective, in securing the extinction of slavery;

happily it had inserted in the declaration of

[Pg. 18]

rights prefixed to its constitution: "All men are

born free and equal, and have certain natural, essential

and inalienable rights."1 This clause

received at a later time strict interpretation at the

bar of the state supreme court, and slavery was held to

have ceased with the year 1780.

There is little to be said about the remaining group of

states with which we are here concerned. Their

territorial organizations were effected under the

provision of the Ordinance of 1787. One of the

most important of these provisions is as follows:

"There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary

servitude in the said Territory, otherwise than in the

punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been

duly convicted."2 It was this feature,

introduced into the great Ordinance by New England men,

that rendered futile the many attempts subsequently made

by Indiana Territory to have slavery admitted within its

own boundaries by congressional enactment. "It is

probable," says Rhodes, "that had it not been for the

prohibitory clause, slavery would have gained such a

foothold in Indiana and Illinois that the two would have

been organized as slaveholding states"3

The five states, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan and

Wisconsin were therefore admitted to the Union as free

states. West of the Mississippi River there is one

state, at least, that must be added to the group just

indicated, namely, Iowa. Slaveholding was

prevented within its domain by the Act of Congress of

1820, prohibiting slavery in the territory acquired

under the Louisiana purchase north of latitude 36°

30', and several years before this law was abrogated

Iowa had entered statehood with the constitution that

fixed her place among the free commonwealth. The

enfranchisement of this extended region was thus

accomplished by state and national action. The

ominous result was the establishment of a sweeping line

of frontier between the slaveholding South and the

non-slaveholding North, and thereby the propounding to

the nation of a new question,

---------------

1

Constitution of Massachusetts, Part I, Art. 1; quoted by

Du Bois, Suppression of the Slave Trade, p. 225

2 See Appendix A, p 359

3 History of the United States, Vol.

I, p. 16.

[Pg. 19] - RENDITION OF FUGITIVES

IN THE COLONIES

that of the status of fugitives in free regions.

The elements were in the proper condition for the

crystallization of this question.

The colonies generally had found it necessary to

provide regulations in regard to fugitives and the

restoration of them to their masters. Such

provisions, it is probable, were reasonably well

observed as long as runaways did not escape beyond the

borders of the colonies to which their owners belonged;

but escapes from the territory of one colony into that

of another were at first left to be settled as the state

of feeling existing between the two peoples concerned

should dictate. In 1643 the New England

Confederation of Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut

and New Haven, unwilling to leave the subject of the

delivery of fugitives longer to intercolonial comity,

incorporated a clause in their Articles of Confederation

providing: "If any servant runn away from

his master into any other of these confederated

Jurisdiccons, That in such case vpon the Certyficate of

one Majistrate in the Jurisdiccon out of which the said

servant fled, or upon other due proofs, the said servant

shall be deliuered either to his Master or any other

that pursues and brings such Certificate or proofe."

About the same time an agreement was entered into

between the Dutch at New Netherlands and the English at

New Haven for the mutual surrender of fugitives, a step

that was preceded by a complaint from the commissioners

of the United Colonies to Governor Stuyvesant of New

Netherlands, to the effect that the Dutch agent at

Hartford was harboring one of their Indian slaves, and

by the refusal to return some of Stuyvesant's runaway

servants from New Haven until the redress of the

grievance. It was only when some of the fugitives

had been restored to New Netherlands, and a

proclamation, issued in a spirit of retaliation by the

Lords of the West Indian Company, forbidding the

rendition of fugitive slaves to New Haven, had been

annulled, that the agreement for the mutual surrender of

runaways was made by the two parties..

Negotiations in regard to fugitives early took place

between Maryland and New Netherlands; at one time on

account of the flight of some slaves from the Southern

colony into the Northern colony, and later on account of

the reversal of the

[Pg. 20] - FUGITIVE SLAVE CLAUSE IN

THE CONSTITUTION

conditions. The temper of the Dutch when

calling for their servants in 1859 was not conciliatory,

for they threatened, if their demand should be refused,

"to publish free liberty, access and recess to all

planters, servants, negroes, fugitives, and runaways

which may go into New Netherland." The escape of

fugitives from the Eastern colonies northward to Canada

and also a constant source of trouble between the French

and the Dutch, and between the French and English.1

When, therefore, emancipation acts were passed by

Vermont and four other states the new question came into

existence. It presented itself also in the Western

territories. The framers of the Northwest

Ordinance found themselves confronted by the question,

and they dealt with it in the spirit of compromise.

They enacted a stipulation for the territory, "that any

person escaping into the same, from whom labor or

service is lawfully claimed in any one of the original

states, such fugitive may be lawfully reclaimed and

conveyed to the person claiming his or her labor or

service aforesaid."2

Meanwhile the Federal Convention in Philadelphia had

the same question to consider. The result of its

deliberations on the point was not different from that

of Congress expressed in the Ordinance. Among the

concessions to slavery that the Federal Convention felt

constrained to make, this provision found place in the

Constitution: "No person held to service or labor in one

state under the laws thereof, escaping into another,

shall, in consequence of any law or regulation therein,

be discharged from such service or labor, but shall be

delivered up on claim of the party to whom such service

or labor may be due."3 Neither of these

clauses appears to have been subjected to much debate,

and they were adopted by votes that testify to their

acceptableness; the former received the support of all

members present but one, the latter passed unanimously.

In the sentiment of the time there seems to have been

no

---------------

1. M. G. McDougall, Fugitive Slaves,

pp. 2-11

2. Journals of Congress, XII, 84, 92

3. Constitution of the United States, Art.

IV, §2. See

Revised Statutes of the United States, I, 18.

See also Appendix A, p. 359.

[Pg. 21] - FUGITIVE SLAVE CLAUSE IN THE

CONSTITUTION.

sense of humiliation on the part of

the North over the conclusions reached concerning the

rendition of escaped slaves. It had been seen by

Northern men that the subject was one requiring

conciliatory treatment, if it were not to become a block

in the way of certain Southern states entering the

Union; and, besides, the opinion generally prevailed

that slavery would gradually disappear from all the

states, and the riddle would thus solve itself.1 The

South was pleased, but apparently not exultant, over the

supposed security gained for its slave property.

General C. C. Pinckney, of South Carolina,

probably expressed the view of most Southerners when he

said that the terms for the security of slave property

gained by his section were not bad, although they were

not the best from the slaveholders' standpoint, and that

they permitted the recapture of runaways in any part of

America—a right the South had never before enjoyed.2

In abstract law the rights of the slave-owner had in

truth been well provided for. Especially deserving of

note is the fact that a constitutional basis had been

furnished for claims which, in case slavery did not

disappear from the country - a contingency not

anticipated by the fathers - might be insisted upon as

having the fundamental and positive sanction of the

government. But what would be the fate of the

running slave was a matter with which, after all,

private principles and sympathies, and not merely

constitutional provisions, would have a good deal to do

in each case.

For several years the stipulations for the rendition of

fugitive slaves remained inoperative. At length,

in 1791, a case of kidnapping occurred at Washington,

Pennsylvania, and this served to bring the subject once

more to the public mind. Early in 1793

Congress passed the first Fugitive Slave Law.3

This law provided for the reclamation of fugitives from

justice and fugitives from labor. We are concerned, of

course, with the latter class only. The sections

of the act dealing with this division are too long to be

here quoted:

---------------

1 Elliot's Debates. See also George

Livermore's Historical Research Respecting the

Opinions of the Founders of the Republic on Negroes, as

Citizens and as Soldiers, 1862, p. 51 et seq.

2 Elliot's Debates, III, 277.

3 Appendiz A, pp. 359-361

[Pg. 22]

they empowered the owner, his agent or

attorney, to seize the fugitive and take him before a

United States circuit or district judge within the state

where the arrest was made, or before any local

magistrate within the county in which the seizure

occurred. The oral testimony of the claimant, or

an affidavit from a magistrate in the state from which

he came, must certify that the fugitive owed service as

claimed. Upon such showing the claimant secured

his warrant for removing the runaway to the state or

territory from which he had fled. Five hundred

dollars fine constituted the penalty for hindering

arrest, or for rescuing or harboring the fugitive after

notice that he or she was a fugitive from labor.

All the evidence goes to show that this law was

ineffectual; Mrs. McDougall points out that two

cases of resistance to the principle of the act occurred

before the close of 1793.1 Attempts at

amendment were made in Congress as early as the winter

of 1796, and were repeated at irregular intervals down

to 1850. Secret or "underground" methods of rescue

were already well understood in and around Philadelphia

by 1804. Ohio and Pennsylvania, and perhaps other

states, heeded the complaints of neighboring slave

states, and gave what force they might to the law of

1793 by enacting laws for the recovery of fugitives

within their borders. The law of Pennsylvania for

this purpose was passed the same year in which Mr.

Clay, then Secretary of State, began negotiations

with England looking toward the extradition of slaves

from Canada (1826); but it was quashed by the decision

of the United States Supreme Court in the Prigg

case in 1842.2 By 1850 the Northern

states were traversed by numerous lines of Underground

Railroad, and the South was declaring its losses of

slave property to be enormous.

The result of the frequent transgressions of the

Fugitive Slave Law on the one hand and of the clamorous

demand for a measure adequate to the needs of the South

on the other, was the passage of a new Fugitive Recovery

Bill in 1850.3 The

---------------

1 Fugitive Slaves, p. 19

2 See Chap. I, pp. 259-267 also Stroud, Sketch of

the Laws Relating to Slavery in the Several States,

2d ed., pp. 220-222.

3 Appendiz A, pp. 361-366

[Pg. 23] - FUGITIVE SLAVE LAW OF 1850

increased rigor of the provisions of

this act was ill adapted to generate the respect that a

good law secures, and, indeed, must have in order to be

enforced. The law contained features sufficiently

objectionable to make many converts to the cause of the

abolitionists; and a systematic evasion of the law was

regarded as an imperative duty by thousands. The

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 was based on the earlier law,

but was fitted out with a number of clauses, dictated by

a self interest on the part of the South that ignored

the rights of every party save those of the master.

Under the regulations of the act the certificate

authorizing the arrest and removal of a fugitive slave

was to be granted to the claimant by the United States

commissioner, the courts, or the judge of the proper

circuit, district, or county. If the arrest were

made without process, the claimant was to take the

fugitive forthwith before the commissioner or other

official, and there the case was to be determined in a

summary manner. The refusal of a United States

marshal or his deputies to execute a commissioner's

certificate, properly directed, involved a fine of one

thousand dollars; and failure to prevent the escape of

the negro after arrest, made the marshal liable, on his

official bond, for the value of the value of the slave.

When necessary to insure a faithful observance of the

fugitive slave clause in the Constitution, the

commissioners, or persons appointed by them, had the

authority to summon the posse comitatus of the county,

and "all good citizens" were "commanded to aid and

assist in the prompt and efficient execution" of the

law. The testimony of the alleged fugitive could

not be received in evidence. Ownership was

determined by the simple affidavit of the person

claiming the slave; and when determined it was shielded

by the certificate of the commissioner

from "all molestation . . . by any process issued by any

court, judge, magistrate, or other person whomsoever."

Any act meant to obstruct the claimant in his arrest of

the fugitive, or any attempt to rescue, harbor, or

conceal the fugitive, laid the person interfering liable

"to a fine not exceeding one thousand dollars, and

imprisonment not exceeding six months," also liable for

"civil damages to the party injured in the sum of one

thousand dollars for each fugitive so

[Pg. 24]

lost.” In all cases where the

proceedings took place before a commissioner he was

“entitled to a fee of ten dollars in full for his

services,” provided that a warrant for the fugitive’s

arrest was issued; if, however, the fugitive was

discharged, the commissioner was entitled to five

dollars only.1

By the abolitionists, at whom it was directed, this law

was detested. A government, whose first national

manifesto contained the exalted principles enshrined in

the Declaration of Independence, stooping to the task of

slave-catching, violated all their ideas of national

dignity, ecency and consistency. Many persons,

indeed, justified their opposition to the law in the

familiar words: “We hold these truths to be

self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they

are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable

rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the

pursuit of happiness.” The scriptural injunction

“not to deliver unto his master the servant that hath

escaped,” 2 was also frequently quoted by men

whose religious convictions admitted of no compromise.

They pointed out that the law virtually made all

Northern citizens accomplices in what they denominated

the crime of slave-catching; that it denied the right of

trial by jury, resting the question of lifelong liberty

on ex-parte evidence; made ineffective the writ of

habeas corpus; and offered a bribe to the commissioner

for a decision against the negro.3 The

penalties of fine and imprisonment for offenders against

the law were severe, but they had no deterrent effect

upon j those engaged in helping slaves to Canada.

On the contrary, the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

stimulated the work of secret emancipation. “The

passage of the new law,” says a recent investigator,

“probably increased the number of anti-slavery people

more than anything else that had occurred during the

whole agitation. Many of those formerly

indifferent were roused to active opposition by a sense

of the injustice of the Fugitive Slave Act as they saw

it executed in Boston and

---------------

1 Statutes at Large,

IX, 462-465

2 Deut. xxiii, 15, 16

3 See Some Recollections of the Anti-Slavery

Conflict, by S. J. May, p. 345 et seq.;

Stroud's Sketch of the Laws Relating to Slavery in

the Several States, 2d ed., 1856, pp. 271-280;

Wilson, History of the Rise and Fall of the Slave

Power, Vol. II, pp. 304-322

[Pg. 25] - DESIRE FOR FREEDOM AMONG SLAVES

elsewhere. . . . As Mr. James

Freeman Clarke has said, ‘It was impossible to

convince the people that it was right to send hack to

slavery men who were so desirous of freedom as to run

such risks. All education from boyhood up to

manhood had taught us to believe that it was the duty of

all men to struggle for freedom.’ ”1

The desire for freedom was in the mind of nearly every

enslaved negro. Liberty was the subject of the

dreams and visions of slave preachers and sibyls; it was

the object of their prayers. The plaintive songs

of the enslaved race were full of the thought of

freedom. It has been well said that “one of the

finest touches in Uncle Tom’s Cabin is the joyful

expression of Uncle Tom when told by his good and

indulgent master that he should be set free and sent

back to his old home in Kentucky. In attributing

the common desire of humanity to the negro the author

was as true as she was effective.”2 To slaves

living in the vicinity, Mexico and Florida early

afforded a welcome refuge. Forests, islands and

swamps within the Southern states were favorite places

of resort for runaways. The Great Dismal Swamp

became the abode of a large colony of these refugees,

whose lives were spent in its dark recesses, and whose

families were reared and buried there. Even in

this retreat, however, the negroes were not beyond

molestation, for they were systematically hunted by men

with dogs and guns.3 Scraps of

information about Canada and the Northern states were

gleaned and treasured by minds recognizing their own

degradation, but scarcely knowing how to take the first

step towards the betterment of their condition.

There can be no doubt that the form in which slavery

existed in the South during the opening decade of the

present century was comparatively mild; but it is quite

clear that it soon exchanged this character for one from

which the amen-

---------------

1 M. G.

McDougall, Fugitive Slaves, p. 43; J. F. Clarke,

Anti-Slavery Days, p. 92.

2 Rhodes, History of the United States,

Vol. I, p. 377.

3 F. L. Olmsted, JOurney in the Bank

Country, p. 155; Rev. W. M. Mitchell, The

Underground Railroad, pp. 72, 73; M. G. McDougall,

Fugitive Slaves, p. 57.

[Pg. 26]

ities of the patriarchal type had

practically disappeared. With the rapid expansion

of the industries peculiar to the South after the

opening up of the Louisiana purchase, the invention of

the cotton gin, and the removal of the Indians from the

Gulf states, came the era of the slave's dismay.

The auction block and the brutal overseer became his

dread while awake, his nightmare when asleep. That

his fears were not ill founded is proved by the activity

of the slave-marts of Baltimore, Richard, New Orleans

and Washington from the time of the migrations to the

Mississippi territory until the War. Alabama is

said to have bought millions of dollars worth of slaves

from the border states up to 1849. Dew estimated

that six thousand slaves were carried from Virginia,

though not all of these were sold to other states.1

The fear of sale to the far South must have stimulated

slaves to flight. That the number of escapes did

increase is deduced from the consenus of abolitionist

testimony. Our sole reliance is upon this

testimony until the appearance of the the United States

census reports for 1850 and I860;2 and the

exhibits on fugitive slaves in these compendiums we are

constrained by various considerations to regard as

inadequate. However, the flight of slaves from the

South was not what the new conditions would readily

account for. We must conclude, therefore, that the

deterring effect of ignorance and the sense of the

difficulties in the way were reenforced after 1840 by

increased vigilance on the part of the slave-owning

class, owing to the rise in value of slave property.

“Since 1840,” says a careful observer, “the high price

of slaves may be supposed . . . to have increased the

vigilance and energy with which the recapture of

fugitives is followed up, and to have augmented the

number of free negroes reduced to slavery by kidnappers.

Indeed it has led to a proposition being quite seriously

entertained in Virginia, of enslaving the whole body of

the free negroes in that state by legislative

enactment.”3 Then, too, the negro’s

attachment

---------------

1 Edward Ingle, Southern Side-Lights,

p. 293.

2 These reports will be dealt with in

another connection. See Chapt. IX, pp. 342, 343.

3 G. M. Weston, Progress of Slavery in

the United States, Wasington, D. C., 1858, pp. 22,

23.

[Pg. 27] - INCENTIVES TO FLIGHT

to the land of his birth, and to his kindred, when

these were not torn from him, must be allowed to have

hindered flight in many instances; when, however, the

appearance of dreaded slave-dealer, or the brutality of

the overseer or the master, spread dismay among the

hands of a plantation, flights were likely to follow.

This was sometimes the case, too, when by the death of a

planter the division of his property among his heirs was

made necessary. William Johnson, of

Windsor, Ontario, ran away from his Kentucky master

because he was threatened with being sent South to the

cotton and rice fields.1 Horace Washington

of Windsor, after working nearly two years for a man

that had a claim on him for one hundred and twenty-five

dollars, reminded his employer that the original

agreement required but one year's labor, and asked for

release. Getting no satisfaction, and fearing

sale, he fled to Canada.2 Lewis Richardson,

one of the slaves of Henry Clay, sought relief in

flight after receiving a hundred and fifty stripes from

Mr. Clay's overseer.3 William Edwards,

of Amherstburg, Ontario, left his master on account of a

severe flogging.4 One of the station-keepers of an

underground line in Morgan County, Ohio, recalls an

instance of a family of seven fugitives giving as the

cause of their flight the death of their master, and teh

expected scattering of their number when the division of

the estate should occur.5

It has already been remarked that slaves began to find

their way to Canada before the opening of hte present

century, but information in regard to that country as a

place of refuge can scarcely be said to have come into

circulation before the War of 1812. The hostile

relations existing between the two nations at that time

caused negroes of sagacious minds to seek their liberty

among the enemies of the United States.6 Then,

too, soldiers returning from the War to their homes in

Kentucky

---------------

1 Conversation with William Johnson,

Windsor, Ontario, July, 1895

2 Conversation with Horace Washington,

Windsor, Ontario, Aug. 2, 1805.

3 The Liberator, April 10, 1846

4 Conversation with William Edwards,

Amherstburg, Ontario, Aug. 3, 1895.

[Pg. 28]

and Virginia brought the news of the disposition of

the Canadian government to defend the rightgs of the

self-emancipated slaves under its jurisdiction. Rumors

of this sort gave hope and courage to the blacks that

heard it, and, doubtless, the welcome reports were

spread by these among trusted companions and friends.

By 1815 fugitives were crossing the Western Reserve in

Ohio, and regular stations of the Underground Railroad

were lending them assistance in that and other portions

of the state.1

After the discovery of Canada by colored refugees from

the Southern states, it was, presumably, not long before

some of the, returning for their families and friends,

gave circulation in a limited way to reports more

substantial than the vague rumors hitherto afloat.

Among the escaped slaves that carried the promise of

Canadian liberty across Mason and Dixon's line were such

successful abductors as Josiah Henson and

Harriet Tubman. In 1860 it was estimated that

the number of negroes that journeyed annually from

Canada to the slave states to rescue their fellows was

about five hundred. It was said that these persons

"carried the Underground Railroad and the Underground

Telegraph into nearly every Southern state.; 2

The work done by these fugitives was supplemented by the

cautious dissemination of news by white persons that

went into the South to abduct slaves or encourage them

to escape, or while engaged there in legitimate

occupations used their opportunities to pass the helpful

word or to afford more substantial aid. The

Rev. Calvin Fairbank, the Rev. Charles T. Torrey

and Dr. Alexander M. Rose may be cited as notable

examples of this class. The latter, a citizen of

Canada, made extensive tours through various slave

states for the express purpose of spreading information

about Canada and the routes by which that country could

be reached. He made trips into Maryland, Kentucky,

Virginia and Tennessee, and did not think it too great a

risk to make excursions into the more southern states.

He went to New Orleans, and from that point set out on a

journey, in the course of which he visited

---------------

1 Wilson, History of the Rise and

Fall of the Slave Power, Vol. II, p. 63

2 Redpath, The Public Life of

Captain John Brown, p. 229

[Pg. 29] - KNOWLEDGE OF CANADA AMONG SLAVES

Vicksburg, Selma and Columbus,

Mississippi, Augusta, Georgia, and Charleston, South

Carolina.1

Considering the comparative freedom of movement between

the slave and the free states along the border, it is

easy to understand how slaves in Maryland, Virginia,

Kentucky and Missouri might pick up information about

the “Land of Promise” to the northward. Isaac

White, a slave of Kanawha County, Virginia, was

shown a map and instructed how to get to Canada by a man

from Cleveland, Ohio. Allen Sidney,

a negro who ran a steamboat on the Tennessee River for

his master, first learned of Canada from an abolitionist

at Florence, Alabama.2 Until the

contest over the peculiar institution had become heated,

it was not an uncommon thing for slaves to be sent on

errands, or even hired out to residents of the border

counties of the free states. Notwithstanding

Ohio’s political antagonism to slavery from the

beginning, there was a “tacit tolerance” of slavery by

the people of the state down to about 1835; and “numbers

of slaves, as many as two thousand it was sometimes

supposed, were hired . . . from Virginia and Kentucky,

chiefly by farmers.” Doubtless such persons heard

more or less about Canada, and when the agitation

against slavery became vehement, they were approached by

friends, and many were induced to accept transportation

to the Queen’s dominions.3

Depredations of this sort caused alarm among

slaveholders. They sought to deter their chattels

from flight by talking freely before them about the

rigors of the climate and the poverty of the soil of

Canada. Such talk was wasted on the slaves, who

were shrewd enough to discern the real meaning of their

masters. They were alert to gather all that was

said, and interpret it in the light of rumors from other

sources. Thus, masters themselves became

disseminators of information

---------------

1 Dr. A. M.

Ross, Recollections and Experiences of an

Abolitionist, 2d ed., 1876, pp. 10, 11, 16, 39.

2 Conversation with White and Sidney in

Canada West, August, 1895.

3 Rufus King, Ohio, in American

Commonwealths, pp. 364, 365, relates that some of

these slaves were discharged from servitude “by writs of

habeas corpus procured in their names,” and that

“numbers were abducted from the slave states and

concealed, or smuggled by the ‘Underground Railroad’

into Canada.”

[Pg. 30]

they meant to withhold. In this

and other ways the slaves of the border states heard of

Canada. The sale of some of these slaves to the

South helps to explain the knowledge of Canada possessed

by many blacks in those distant parts. When Mr.

Ross visited Vicksburg, Mississippi, he found

that “many of these negroes had heard of Canada from the

negroes brought from Virginia and the border slave

states; but the impression they had was that, Canada

being so far away, it would be useless to try to reach

it.”1 Notwithstanding the distance, the

number of successful escapes from the interior as well

as from the border slave states seems to have been

sufficient to arouse the suspicion in the minds of

Southerners that a secret organization of abolitionists

had agents at work in the South running off slaves.

This suspicion was brought to light during the trial of

Richard Dillingham in Tennessee in 1849.2

The labors of Mr. Ross several years later

gave color to the same notion. These facts help to

explain the insistence of the lower Southern states on

the passage and strict enforcement of the Fugitive Slave

Law in 1850.

With the growth of a thing so unfavored as was the

Underground Road, local conditions must have a great

deal to do. The characteristics of small and

scattered localities, and even of isolated families, are

of the first importance in the consideration of a

movement such as this. These little communities

were in general the elements out of which the

underground system built itself up. The sources of

the convictions and confidences that knitted these

communities together in defiance of what they considered

unjust law can only be learned by the study of local

conditions. The incorporation in the Constitution

of the compromises concerning slavery doubtless quieted

the consciences of many of the early friends of

universal liberty. It was only natural, however,

that there should be some that would hold such

concessions to be sinful, and in violation of the

principles asserted in the Declaration of Independence

and in the very Preamble of the Constitution itself.

These persons would cling tena-

---------------

1 Dr. A. M. Ross, The

Recollections and Experiences of an Abolitionist, p.

38.

2 A. L. Benedict, Memoir of Richard Dillingham,

p. 17.

[Pg. 31] - FAVORABLE LOCAL CONDITIONS

ciously to their views, and would aid

a fugitive slave whenever one would ask protection and

help. It is not strange that representatives of

this class should be found more frequently among the

Quakers than any other sect. In southeastern

Pennsylvania and in New Jersey the work of helping

slaves to escape was, for the most part, in the hands of

Quakers from the beginning. This was true also of

Wilmington, Delaware, New Bedford, Massachusetts, and

Valley Falls, Rhode Island, as of a number of important

centres in western Pennsylvania, and eastern, central

and southwestern Ohio, in eastern Indiana, in southern

Michigan and in eastern Iowa.

Anti-slavery views prevailed against the first attempts

at enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793 in

Massachusetts, and spread to other localities in the New

England states. When the tide of emigration to the

Western states set in, settlers from New England were

given more frequent occasions to put their principles

into practice in their new homes than they had known in

the seaboard region. The western portions of New

York and Pennsylvania, as well as the neighboring

section of Ohio, called the Western Reserve, are dotted

over with communities where negroes learned the meaning

of Yankee hospitality. Like Joshua R. Giddings,

the people of these communities claimed to have borrowed

their abolition sentiments from the writings of

Jefferson, whose “abolition tract,” Giddings said, “was

called the Declaration of Independence.”1

In northern Illinois there were many centres of the New

England type, though, of course, not all the underground

stations in that region were kept by New Englanders.

In a few neighborhoods settlers from the Southern

states were helpers. These persons had left the

South on account of slavery; they preferred to raise

their families away from influences they felt to be

harmful; and they pitied the slave. It was easy

for them to give shelter to the self-freed negro.

In south central Ohio, in a district of four or five

counties locally known as the old Chillicothe

Presbytery, a number of the early preachers were

anti-slavery men from the Southern

---------------

1 George W. Julian, Life of Joshua B.

Giddings, p. 157.

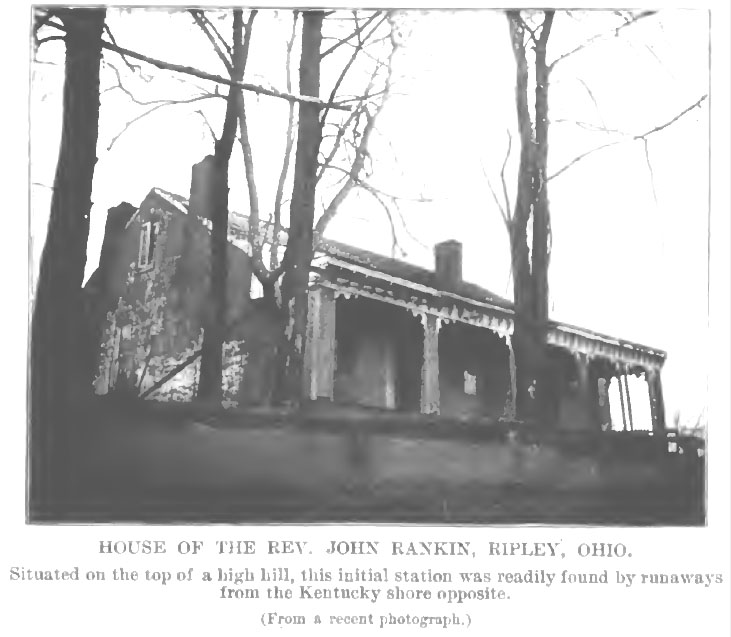

[Pg. 32]

states. Among the number were

John Rankin, of Ripley, James Gilliland,

of Red Oak, Jesse Lockhart, of

Russellville, Robert B. Dobbins, of Sardinia,

Samuel Crothers, of Greenfield, Hugh S.

Fullerton, of Chillicothe, and William

Dickey, of Ross or Fayette County. The

Presbyterian churches over which these men presided

became centres of opposition to slavery, and fugitives

finding their way into the vicinity of any one of them

were likely to receive the needed help.1

The stations in Bond, Putnam and Bureau counties,

Illinois, were kept in part by anti-slavery settlers

from the South. It is a fact worthy of record in

this connection that the teachings of the two sects, the

Scotch Covenanters and the Wesleyan Methodists, did not

exclude the negro from the bonds of Christian

brotherhood, and where churches of either denomination

existed the Road was likely to be found in active

operation. Within the borders of Logan County,

Ohio, there were a number of Covenanter homes that

received fugitives; and in southern Illinois, between

the towns of Chester and Centralia, there was a series

of such hospitable places. There were several

Wesleyan Methodist Stations in Harrison County, Ohio,

and with these were intermixed a few of the Covenanter

denomination.

It was natural that negro settlements in the free

states should be resorted to by fugitive slaves.

The colored people of Greenwich, New Jersey, the Stewart

Settlement of Jackson County, Ohio, the Upper and Lower

Camps, Brown County, Ohio, and the Colored Settlement,

Hamilton County, Indiana, were active. Thelist of

towns and cities in which negroes became coworkers with

white persons in harboring and concealing runaways is a

long one. Oberlin, Portsmouth and Cincinnati,

Ohio, Detroit, Michigan, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and

Boston, Massachusetts, will suffice as examples.

The principles and experience gained by a number of stu-

---------------

1 History of Brown

County, Ohio, p. 313 et seq. Also

letter of Dr. Isaac M. Beck, Sardinia, O., Dec. 26,

1892. Mr. Beck was born in 1807, and knew

personally the clergymen named. He joined the

abolition movement in 1835. His excellent letter

is verified in various points by other correspondents.

[Pg. 33] - ORIGIN OF THE UNDERGROUND MOVEMENT

dents while attending college in

Oberlin did not come amiss later when these young men

established themselves in Iowa. Professor L. F.

Parker, after describing what was probably the

longest line of travel through Iowa for escaped slaves,

says: “Along this line Quakers and Oberlin students were

the chief namable groups whose houses were open to such

travellers more certainly than to white men,”1

and the Rev. William M. Brooks, a graduate of

Oberlin, until recently President of Tabor College,

writes: “The stations . . . in southwestern Iowa were in

the region of Civil Bend, where the colony from Oberlin,

Ohio, settled which afterwards settled Tabor.”2

The origin of the Underground Road dates farther back

than is generally known; though, to be sure, the

different divisions of the Road were not contemporary in

development. Two letters of George

Washington, written in 1786, give the first reports,

as yet known, of systematic efforts for the aid and

protection of fugitive slaves. One of these

letters bears, the date May 12, and the other, November

20. In the former, Washington speaks of the

slave of a certain Mr. Dalby residing at

Alexandria, who has escaped to Philadelphia, and “whom a

society of Quakers in the city, formed for such

purposes, have attempted to liberate.”3

In the latter he writes of a slave whom he sent “under

the care of a trusty overseer” to the Hon. William

Drayton, but who afterwards escaped. He says:

“The gentleman to whose care I sent him has promised

every endeavor to apprehend him, but it is not easy to

do this, when there are numbers who would rather

facilitate the escape of slaves than apprehend them when

runaways.”4 The difficulties attending

the pursuit of the Drayton slave, like those in the

other case mentioned, seem to have been associated in

Washington’s mind with the procedure of certain

citizens of Pennsylvania; it is quite possible that he

was again referring to the Quaker

---------------

1 Letter from Professor L. F. Parker, Grinell, Iowa,

Aug. 3, 1894.

2 Letter from President W. M. Brooks, Tabor, Iowa, Oct.

11, 1894.

3 Sparks's Washington, IX, 158, quoted in

Quakers of Pennsylvania, by Dr. A. C. Applegarth,

Johns Hopkins Studies, X, p. 463.

4. Lunt, Origin of the Late War, Vol. I, p. 20.

[Pg. 34]

society in Philadelphia. However

that may be, it appears probable that the record of

Philadelphia as a centre of active sympathy with the

fugitive slave was continuous from the time of

Washington's letters. In 1787 Isaac T.

Hopper, who soon became known as a friend of slaves,

settles in Philadelphia, and, although only sixteen or

seventeen years old, had already taken a resolution to

befriend the oppressed Africans.1 Some

case of kidnapping that occurred in Columbia,

Pennsylvania, in 1804, stirred the citizens of that town

to intervention in the runaways' behalf; and the

movement seems to have spread rapidly among the Quakers

of Chester, Lancaster, York, Montgomery, Berks and Bucks

counties.2 New Jersey was probably not

behind southeastern Pennsylvania in point of time in

Underground Railroad work. This is to be inferred

from the fact that the adjacent parts of the two states

were largely settled by people of a sect distinctly

opposed to slavery, and were knitted together by those

times of blood that are known to have been favorable in

other quarters to the development of underground routes.

That protection was given to fugitives early in

the present century by the Quakers of southwestern New

Jersey can scarcely be doubted; and we are told that

negroes were being transported through New Jersey before

1818.3 New York was closely allied with

the New Jersey and Philadelphia centres as far back as

our meagre records will permit us to go. Isaac

T. Hopper, who had grown familiar with underground

methods of procedure in Philadelphia, moved to New York

in 1829. No doubt his philanthropic arts were soon

mae use of there, for in 1835 we find him accused,

---------------

1 L. Maria Child, Life of Isaa T. Hopper, 1854,

p. 35.

2 History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, R. C.

Smedley's article on the "Underground Railroad," p. 426;

also Smedley, Underground Railroad, p. 26.

3. The Rev. Thomas C. Oliver, born and raised in Salem,

N. J. says that the work of the Underground Railroad was

going on before he was born, (1818) and continued until

the time of the War. Mr. Oliver was railsed

in the family of Thomas Clement, a member of the

Society of Friends. He graduated fro the

Princeton Theological Seminary in 1856. As a youth

he began to take part in rescues. Although

seventy-five years old when visited by the author, he

was vigorous in boy and mind, and seemed to have a

remarkably clear memory.

[Pg. 35] - DEVELOPMENT OF THE UNDERGROUND SYSTEM.

though falsely this time, of harboring

a runaway at his store in Pearl Street.1 Frederick

Douglass mentions the assistance rendered by Mr.

Hopper to fugitives in New York; and says that he

himself received aid from David Ruggles, a

colored man and coworker with the venerable Quaker.2

After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, New

York City became more active than ever in receiving and

forwarding refugees.3 This city at the

mouth of the Hudson was the entrepêt

for a line of travel by way of Albany, Syracuse and

Rochester to Canada, and for another line diverging at

Albany, and extending by the way of Troy to the New

England states and Canada; and these routes appear to

have been used at an early date. The Elmira route,

which connected Philadelphia with Niagara Falls by way

of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, was made use of from about

1850 to 1860. Its comparatively late development

is explained by the fact that one of its principal

agents was a fugitive slave. John W. Jones,

who did not settle in Elmira until 1844, and that the

line of the Northern Central Railroad was not completed

until about 1850.4 In western New York

fugitives began to arrive from the neighboring parts of

the Pennsylvania and Ohio between 1835 and 1840, if not

earlier. Professor Edward Orton recalls

that in 1838, soon after his father moved to Buffalo,

two sleigh-loads of negroes from the Western Reserve

were brought to the house in the night-time;s

and Mr. Frederick Nicholson, of Warsaw, New York,

states that the underground work in his vicinity began

in 1840. From this time on there was apparently no

cessa-

---------------

1 L. Maria Child, Life of Isaac T. Hopper, p.

316.

2 History of Florence, Mass., p. 131. Charles A.

Sheffeld, Editor.

3 The Underground Road was

active in New York City at a much earlier date certainly

than Lossing gives. He says, "After the Fugitive

Slave Law, the Underground Railroad was established, and

the city of New York became one of the most important

stations on the road." History of New York,

Vol. II, p. 655.

4 Letter of Mrs. Susan L. Crane, Elmira, Sept. 14,

1896. Mrs. Crane's father, Mr. Jervis Langdon, wsa

active in underground work at Elmira, and had a trusted

co-laborer in John W. Jones, who still lives in Elmira.

5. Conversation with Professor Orton, Ohio State

University, Columbus, O., 1893.

[Pg. 36]

tion of migrations of fugitives into

Canada at Black Rock, Buffalo and other points.1

The remoteness of New England from the slave states did

not prevent its sharing, in the business of helping

blacks to Canada. In Vermont, which seems to have

received fugitives from the Troy line of eastern New

York, the period of activity began “in the latter-part

of the twenties of this century, and lasted till the

time of the Rebellion.”2 In New

Hampshire there was a station at Canaan after 1830, and

probably before that time.3 The Hon.

Mellen Chamberlain, of Chelsea, Massachusetts,

personally conducted a fugitive on two occasions from

Concord, New Hampshire, to his uncle’s at Canterbury, in

the same state “most probably in 1888 or 1839.”4

This thing once begun in New Hampshire seems to have

continued steadily during the decades until the War of

the Rebellion.5 As regards Connecticut

the Rev. Samuel J. May states that as long ago as

1834 slaves were addressed to his care while he was

living in the eastern part of the state.6

In Massachusetts the town of Fall River became an

important station in 1839.7 New

Bedford, Boston, Marblehead, Concord, Springfield,

Florence and other places in Massachusetts are known to

have given shelter to fugitives as they travelled

northward. Mr. Simeon Dodge, of Marblehead,

who had per-

---------------

1 For cases of arrivals of escaped slaves

over some of the western New York branches, see

Sketches in the History of the Underground Railroad,

by Eber M. Pettit, 1879. These sketches were first

published in the Fredonia Censor, the series

closing Nov. 18, 1868.

2 Letter of Mr. Aldis O. Brainerd, St.

Albans, Vt., Oct. 21, 1895.

3 Letter of Mr. Charles E. Lord, Franklin,

Pa., July 6, 1896: "My maternal grandfather, James

Furber, lived for several years in Canaan, N. H., where

his house was one of the stations of the Underground

Railway. His father-in-law, James Harris, who

lived in the same house, had been engaged in helping

fugitive negroes on toward Canada ever since 1830, and

probably before that time."

4 Letter to Judge Mellen Chamberlain,

Chelsea, Mass., Feb. 1, 1896.

5 Letter of Mr. Thomas P. Cheney, Ashland,

N. H., Mar. 30, 1896.

6 Recollections of the Anti-Slavery

Conflict, p. 297.

7 Elizabeth Buffum Chace, Anti-Slavery

Reminiscences, p. 27. Mrs. Chace says:

"From the time of the arrival of James Curry at Fall

River, and his departure for Canada, in 1839, that town

became an important station on the so-called Underground

Railroad." The residence of Mrs. Chace was a place

on refuge from the year named.

[Pg. 37] - ITS SPREAD IN OHIO

sonal knowledge of what was going on,

recollects that the Underground Road was active between

1840 and 1860, and his testimony is substantiated by

that of a number of other persons.1

Doubtless there was underground work going on in

Massachusetts before this period, but it was probably of

a less systematic character. In Maine fugitives

frequently obtained help in the early forties. The

Rev. O. B. Cheney, later President of Bates

College, was concerned in a branch of the Road running

from Portland to Effingham, New Hampshire, and

northward, during the years 1843 to 1845.2

That later conditions probably increased the labors of

the Maine abolitionists appears from the statement of

Mr. Brown Thurston, of Portland, that

he had at one time after the passage of the second

Fugitive Slave Law the care of thirty fugitives.3

Considering the

geographical situation of Ohio and western Pennsylvania,

the period of their settlement, and the character of

many of their pioneers, it is not strange that this work

should have become established in this region earlier

than in the other free states along the Ohio River.

The years 1815 to 1817 witnessed, so far as we now know,

the origin of underground lines in both the eastern and

western parts of this section. Henry Wilson

explains this by saying that soldiers from Virginia and

Kentucky, returning home after the War of 1812, carried

back the news that there was a land of freedom beyond

the lakes. John Sloane, of Ravenna,

David Hudson, the founder of the town of

Hudson, and Owen Brown, the father of

John Brown of Osawattomie, were among the

first of those known to have harbored slaves in the

eastern part.4 Edward Howard,

the father of Colonel D. W. H. Howard, of

Wauseon, and the Ottawa Indians of the village of

Chief Kinjeino were among the earliest

friends of fugitives

---------------

1 Concerning

Springfield, Mass. see Mason A. Green's History of

Springfield, pp. 470, 471. For the

sentiment of New Bedford, see Ellis's History of New

Bedford, pp. 306, 307.

2 Letter of the Rev. O. B. Cheney, Pawtuxet,

R. I., Apr. 8, 1896.

3 Letter of Mr. Brown Thurston, Portland,

Me., Oct. 21, 1895.

4 Wilson, Rise and Fall of the Slave

Power, Vol. II, p. 63; Alexander Black, The Story

of Ohio, see account of the Underground Railroad.

[Pg. 38]

in the western part.1

At least one case of underground procedure is reported

to have occurred in central Ohio as early as 1812.

The report is but one remove from its original source,

and was given to Mr. Robert McCrory, of

Marysville, Ohio, by Richard Dixon, an

eye-witness. The alleged runaway, seized at

Delaware, was unceremoniously taken from the custody of

his mounted captor when the two reached Worthington, and

was brought before Colonel James Kilbourne, who

served as an official of all work in the village he had

founded but a few years before. By Mr.

Kilbourne’s decision, the negro was released, and

was then sent north aboard one of the government wagons

engaged at the time in carrying military supplies to

Sandusky.2 That such action was not

inconsistent with the character of Colonel

Kilbourne and his New England associates is

evidenced by the fact that as an agent for “The Scioto

Company,” formed in Granby, Connecticut, in the winter

of 1801-1802, he had delayed the purchase of a township

in Ohio for settlement until a state constitution

forbidding slavery should be adopted.3

If now the testimony of the oldest surviving

abolitionists from the different regions of the state be

compared, some interesting results may be found.

Job Mullin, a Quaker of Warren County, in

his eighty-ninth year when his statement was given,

says: “The most active time to my knowledge was from

1816 to 1830. . . .” In 1829 Mr. Mullin

moved off the line with which he had been connected and

took no further part in the work.4

Mr. Eliakim H. Moore, for a number of years the

treasurer of Ohio University at Athens, says that the

work began near Athens during 1823 and 1824. “In

those years not so many attempted to escape as later,

from 1845 to 1860.”5 Dr.

Thomas Cowgill, an aged Quaker of Kennard,

Champaign County, recollects that the work of the

Underground Railroad began in his

---------------

1 Letter of Col. D. W. H. Howard, Wauseon, O., Aug. 22,

1894.

2 Conversaton with Robert McCrory, Marysville, O.,

Sept. 30, 1898. Mr. McCrory was educated at

Oberlin College, and has an excellent memory.

3 Howe's Historical Collections of Ohio, Vol. I,

p. 614.

4. Letter from Job Mullin, dictated to his son-in-law,

W. H. Newport, at Springboro, O., Sept. 9, 1895.

5. Conversation with Mr. Eliakim H. Moore, Athens, O.

[Pg. 39] - ITS SPREAD IN OHIO

neighborhood about 1824. The

time between 1840 and the passage of the Fugitive Slave

Law he regards as the period of greatest activity within

his experience. Joseph Skillgess, a colored

citizen of Urbana, now seventy-six years old, says that

it is among his earliest recollections that runaways

were entertained at Dry Run Church, in Ross County.1

William A. Johnston, an old resident of

Coshocton, testifies: "We had such a road here as

early as the twenties, I know from tradition and

personal observation."2 Mahlon

Pickrell, a prominent Quaker of Logan County,

writes: "There was some travel on the Underground

Railroad as early as 1820, but the period of greatest

activity in this vicinity was between 1840 and 1850."3

Finally, Mr. R. C. Corwin, of Lebanon, writes:

"My first recollection of the business dates back to

about 1820, when I remember seeing fugitives at my

father's house, though I dare say it had been going on

long before that time. From that time until 1840

there was a gradual increase of business. From

1840 to 1860 might be called the period of greatest

activity."4 Among these aged witnesses,

those have been quoted whose experience, character and

clearness of mind gave weight to their words.

Mr. Rush R. Sloane, of Sandusky, who made some local

investigations in northwestern Ohio and published the

results in 1888, produces some evidence that agrees with

the testimony just given. He found that, "The

first runaway slave known as such at Sandusky was there

in the fall of the year 1820 . . . . Judge Jabez

Wright, one of the three associate judges who held

the first term of court in Huron County in 1815, was

among the first white men upon the Firelands to aid

fugitive slaves; he never failed when opportunity

offered to lend a helping hand to the fugitives,

secreting them when necessary, feeding them when they

were hungry, clothing an employing them."5

After reciting a number of instances of rescus occurring

between 1820 and 1850, Mr. Sloane remarks

---------------

1 Conversation with

Joseph Skillgess, Urbana, O., Aug. 14, 1894.

2 Letter of Wm. A. Johnston, Coshocton, O., Aug. 23,

1894.

3 Letter of Hannah W. Blackburn, for her father, Mahlon

Pickrell, Zanesfield, O., Mar. 25, 1893.

4. letter of R. C. Corwin, Lebanon, O., Sept. 11, 1895.

5. The Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888, p. 84.

[Pg. 40]

that one of the immediate results of

the passage of the second Fugitive Slave Law was the

increased travel of fugitives through the State of Ohio.1

The foregoing items have been brought together to show

that there was no break in the business of the Road from

the beginning to the end. The death or the change

of residence of abolitionists may have interrupted

travel on one or another route, and may even have broken

a line permanently, but the history of the Underground

Railroad system in Ohio is continuous.

In North Carolina underground methods are known to have

been employed by white persons of respectability as

early as 1819. We are informed that “Vestal

Coffin organized the Underground Railroad near

the present Guilford College in 1819. Addison

Coffin, his son, entered its service as a

conductor in early youth and still survives in hale old

age. . . . Vestal’s cousin, Levi Coffin,

became an antislavery apostle in early youth and

continued unflinching to the end. His early years

were spent in North Carolina, whence he helped many

slaves to reach the West.”2 Levi

Coffin removed to Indiana in 1826. Of his

own and his cousin’s activities in behalf of slaves

while still a resident of North Carolina, Mr.

Coffin writes: “Runaway slaves used frequently to

conceal themselves in the woods and thickets of New

Garden, waiting opportunities to make their escape to

the North, and I generally learned their places of

concealment and rendered them all the service in my

power. . . . These outlying slaves knew where I lived,

and, when reduced to extremity of want or danger, often

came to my room, in the silence and darkness of the

night, to obtain food or assistance. In my efforts

to aid these fugitives I had a zealous coworker in my

friend and cousin Vestal Coffin, who was

then, and continued to the time of his death - a

few years later - a staunch friend to the slave.”3

When Levi Coffin emigrated in 1826 to

southeastern Indiana, he did not give up his active

interest in the fleeing slave, and his house at Newport

(now Fountain City) became a centre

---------------

1 The Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888, p. 34 et

seq

2 Stephen B. Weeks,

Southern Quakers and Slavery, p. 242.

3. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, 2d. ed., pp.

20, 21.

[Pg. 41] - EARLY ACTIVITIES IN ILLINOIS

at which three distinct lines of

Underground Road converged. It is probable, however,

that wayfarers from bondage found aid from pioneer

settlers in Indiana before Friend Coffin’s

arrival. John F. Williams, of Economy,

Indiana, says that fugitives “commenced coming in 1820,”

and he denominated himself “an agent since 1820,”

although he “never kept a depot till 1852.”1

It is scarcely necessary to make a showing of testimony

to prove that an expansion of routes like that taking

place in Ohio and states farther east occurred also in

Indiana.

It is doubtful at what time stations first came to

exist in Illinois. Mr. H. B. Leeper, an old

resident of that state, assigns their origin to the

years 1819 and 1820, at which time a small colony of

anti-slavery people from Brown County, Ohio, settled in

Bond County, southern Illinois. Emigrations from

this locality to Putnam County, about 1830, led, he

thinks, to the establishment there of a new centre for

this work. These settlers were persons that had

left South Carolina on account of slavery, and during

their residence in Brown County, Ohio, had accepted the

abolitionist views of the Rev. James Gilliland, a

Presbyterian preacher of Red Oak; and in Illinois they

did not shrink from putting their principles into

practice. This account is plausible, and as it is

substantiated in certain parts by facts from the history

of Brown County, Ohio, it may be considered probable in

those parts that are and must remain without

corroboration. Concerning his father Mr.

Leeper writes: “John Leeper moved from

Marshall County, Tennessee, to Bond County, Illinois, in

1816. Was a hater of slavery. . . . Remained in

Bond County until 1823, then moved to Jacksonville,

Morgan County, and in 1831 to Putnam County, and in 1833

to Bureau County, Illinois. . . . My father’s house was

always a hiding-place for the fugitive

---------------

1 Letter from

John E. Williams, Economy, Ind., March 21, 1893.

When this letter was written, Mr. Williams was

eighty-one years old. He was, he says, born in

1812. In 1820 he would have been eight years old.

Children were sometimes sent to carry food to refugees

in hiding, or to do other little services with which

they could be safely trusted. Such experiences

were apt to make deep impressions on their young

memories.

[Pg. 42]

from slavery.”1 On

the basis of this testimony, and the probability in the

case, we may believe that the underground movement in

Illinois dates back, at least, to the time of the

admission of Illinois into the Union, that is, to 1818.

Soon after 1835, the movement seems to have become well

established, and to have increased in importance with

considerable rapidity till the War.

It is a fact worthy of note that the years that

witnessed the beginnings in Ohio, Indiana, North

Carolina and Illinois of this curious method of

assailing the slave power, precede but slightly those

that witnessed the formulation of three several bills in

Congress designed to strengthen the first Fugitive Slave

Law. The three measures were drafted during the

interval from 1818 to 1822.

The abolitionist enterprises of the more western

states, Iowa and Kansas, came too late to be in any way

connected with the proposal of these bills. The

settlement of these territories was, of course,

considerably behind that of Ohio, Indiana and Illinois,

but the nearness of the new regions to a slaveholding

section insured the opportunity for Underground Railroad

work as soon as settlement should begin. Professor

L. F. Parker, of Tabor College, Iowa, has sketched

briefly the successive steps in the opening of his state

to occupancy. “The Black-Hawk Purchase opened the

eastern edge of Iowa to the depth of 40 or 50 miles to

the whites in 1833. The strip . . .

west of that which included what is now Grinnell was not

opened to white occupancy till 1843, and it was ten

years later before the white residents in this county

numbered 500. Grinnell was settled in 1854, when

central and western Iowa was merely dotted by a few

hamlets of white men, and seamed by winding paths along

prairie ridges and through bridgeless streams.”2

One of the early settlers in southeastern Iowa was J.

H. B. Armstrong, who had been familiar with the

midnight appeals of escaping

---------------

1 Letter from

H. B. Leeper, Princeton, Ill., received Dec. 19, 1895.

Mr. Leeper is seventy-five years of age. His

letter shows a knowledge of the localities of which he

writes, Bond County in Southwestern Illinois, and

Bureau and Putnam Counties in the central part of the

state.

2 Letter from Professor L. F. Parker,

Grinnell, Iowa, Aug. 30, 1894.

[Pg. 43] - OPERATIONS IN IOWA

slaves in Fayette County, Ohio.

Mr. Armstrong removed to the West in 1839, and

settled in Lee County, Iowa. His proximity to the

northeastern boundary of Missouri seems to have involved

him in Underground Railroad work from the start, on the

route running to Salem and Denmark. When in 1852

Mr. Armstrong moved to Appanoose County, and

located within four miles of the Missouri line, among a

number of abolitionists, he found himself even more

concerned with secret projects to help slaves to Canada.

The lines of travel of fugitive slaves that extended

east throughout the entire length of Iowa were more or

less associated with Kansas men and Kansas movements,

and their development is, therefore, to be assigned to

the time of the outbreak of the struggle over Kansas

(1854). Residents of Tabor in southwestern Iowa,

and of Grinnell in central Iowa, agree in designating

1854 as the year in which their Undergrounds Railroad

labors began. The Rev. John Todd, one of

the founders of the college colony of Tabor, is

authority for the statement that the first fugitives

arrived in the summer of 1854.1

Professor Parker states that Grinnell was a

stopping- place for the hunted slave from the time of

its founding in 1854.

We may summarize our findings in regard to the

expansion of the Underground Railroad, then, by saying

that it had grown into a wide-spread “institution”

before the year 1840, and in several states it had

existed in previous decades. This statement

coincides with the findings of Dr. Samuel G. Howe

in Canada, while on a tour of investigation in 1863.

He reports that the arrivals of runaway slaves in the

provinces, at first rare, increased early in the

century; that some of the fugitives, rejoicing in the

personal freedom they had gained and banishing all fear

of the perils they must endure, went stealthily back to

their former homes and brought away their wives and

children. The Underground Road was of great

assistance to these and other escaping slaves, and

“hundreds,”

--------------

1 Letter from

Professor James E. Todd, Vermillion, South Dakota, Nov.

6, 1894. Professor Todd is the son of the Rev.

John Todd.

The Tabor Beacon, 1890,1891, contains a series

of reminiscences from the pen of the Rev. John Todd.

The first of these recounts the first arrival of

fugitives in July, 1854.

[Pg. 44]

says Dr. Howe, "trod

this path every year, but they did not attract much

public attention."1 It does not escape

Dr. Howe's consideration, however, that

the fugitive slaves in Canada were soon brought to

public notice by the diplomatic negotiations between

England and the United States during the years

1826-1828, the object being, as Mr. Clay,

the Secretary of State, himself declared, "to provide

for a growing evil." The evidence gathered from

surviving abolitionists in the states adjacent to the

lakes shows an increased activity of the Underground

Road during the period 1830-1840. The reason for

flight given by the slave was, in the great majority of

cases, the same, namely, fear of being sold to the far

South. It is certainly significant in this

connection that the decade above mentioned witnessed the

removal of the Indians from the Gulf states, and, in the

words of another contemporary observer and reporter,

"the consequent opening of new and vast cotton fields."2

The swelling emphasis laid upon the value of their

escaped slaves by the Southern representatives in

Congress, and by the South generally, resounded with

terrific force at length in the Fugitive Slave Law of

1850. That act did not, as it appears, check or

diminish in any way the number of underground rescues.

In spite of the exhibit on fugitive slaves made in the

United States census report of 1860, which purports to

show that the number of escapes was about a thousand a

year, it is difficult to doubt the consensus of

testimony of many underground agents, to the effect that

the decade from 1850 to 1860 was the period of the

Road's greatest activity in all sections of the North.3

It is not known when the name "Underground Railroad"

came to be applied to these secret trails, nor where it

was first applied to them. According to Mr.

Smedley the designation came into use among

slave-hunters in the neighborhood of Columbia soon after

the Quakers in southeastern Penn-

---------------

1 S. G. Howe, The Refugees from Slavery

in Canada West, 1864, pages 11, 12.

2 G. M. Weston, Progress of Slavery

in the United States, Washington, D. C., 1858, p. 22

3 Some

conclusions presented in the American Historical

Review, April, 1896, pp. 460-462, are here repeated.

[Pg. 45] - NAMING OF THE ROAD

sylvania began

their concerted action in harboring and forwarding

fugitives. The pursuers seem to have had little

difficulty in tracking slaves as far as Columbia, but

beyond that point all trace of them was generally lost.

All the various methods of detection customary in such

cases were resorted to, but failed to bring the runaways

to view. The mystery enshrouding these

disappearances completely bewildered and baffled the

slave-owners and their agents, who are said to have

declared, "there must be an Underground Railroad

somewhere."1 As this work reached

considerable development in the district indicated

during the first decade of this century the account

quoted is seen to contain an anachronism.

Railroads were not known either in England or the United

States until about 1830, so that the word "railroad"

could scarcely have received its figurative application

as early as Mr. Smedley implies.

The Hon. Rush R. Sloane, of Sandusky, Ohio,

gives the following account of the naming of the Road:

"In the year 1831, a fugitive named Tice

Davids came over the line and lived just back of

Sandusky. He had come direct from Ripley, Ohio,

where he crossed the Ohio River. . . .

"When he was running away, his master, a Kentuckian,

was in close pursuit and pressing him so hard that when

the Ohio River was reached he had no alternative but to

jump in and swim across. It took his master some

time to secure a skiff, in which he and his aid followed

the swimming fugitive, keeping him in sight until he had

landed. Once on shore, however, the master could

not find him. No one had seen him; and after a

long . . . search the disappointed

slave-master went into Ripley, and when inquired of as

to what had become of his slave, said . . .

he thought 'the nigger must have gone off on an

underground road.' The story was repeated with a

good deal of amusement, and this incident gave the name

to the line. First the 'Underground Road,'

afterwards' ' Underground Railroad.' "2

A colored man, the Rev. W. M. Mitchell,

who was for several years a resident of

---------------

1 R. C. Smedley, Underground Railroad, pp. 34,

35.

2 The Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888, p. 35.

[Pg. 46]

southern Ohio, and a friend of fugitives, gives what

appears to be a version of Mr. Sloane's story.1

These anecdotes are hardly morethan traditions,

affording a fair general explanation of the way in which

the Underground Railroad got its name; but they cannot

be trusted in the details of time, place and occasions.

Whatever the manner and date of its suggestion, the

designation was generally accepted as an apt title for

the mysterious means of transporting fugitive slaves to

Canada

---------------

1 The Underground Railroad, pp. 4, 5.

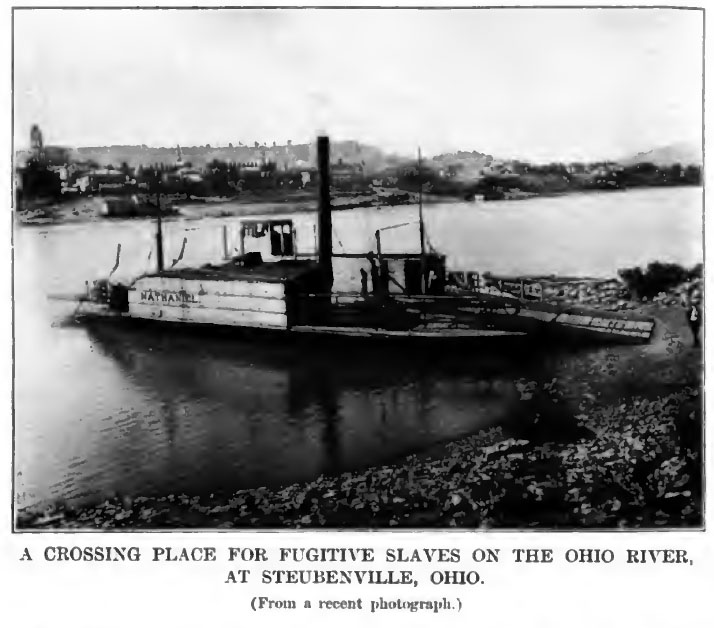

A CROSSING PLACE FOR FUGITIVE SLAVES ON THE OHIO RIVER,

AT STEUBENVILLE, OHIO.

(from a recent photograph)

HOUSE ON THE REV. JOHN RANKIN, RIPLEY,

OHIO.

Situated on the top of a high hill, this initial station

was readily found by runaways from the KEntucky shore

opposite.

(From a recent photograph)

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS |