|

CHAPTER III

THE METHODS OF THE UNDERGROUND

RAILROAD

Pg. 47

By the

enactment of the first Fugitive Slave Law, Feb. 12,

1793, the aiding of fugitive slaves became of penal

offence. This measure laid a fine of five hundred

dollars upon any one harboring escaped slaves, or

preventing their arrest. The provisions of the law

were of a character to stimulate resistance to its

enforcement. The master or his agent was

authorized to arrest the runaway, wherever found; to

bring him before a judge of the circuit or the district

court of the United States, or before a local magistrate

where the capture was made; and to receive, on the

display of satisfactory proof, a certificate operating

as a full warrant for taking the prisoner back to the

state from which he had fled. This summary method

of disposing of cases involving the high question of

human liberty was regarded by many persons as unjust;

they freely denounced it, and, despite the penalty

attached, many violated the law. Secrecy was the

only safeguard of these persons,

as it was of those they were attempting to succor; hence

arose the numerous artifices employed.

The uniform success of the attempts to evade this first

Fugitive Slave Law, and doubtless, also, the general

indisposition of Northern people to take part in the

return of refugees to their Southern owners, led, as

early as in 1823, to negotiations between Kentucky and

the three adjoining states across the Ohio. It is

unnecessary to trace the history of these negotiations,

or to point out the statutes in which the legislative

results are recorded. It is notable that sixteen

years elapsed before the legislature of Ohio passed a

law to secure the recovery of slave property, and that

the new enactment remained on the statute books only

four years. The penalties imposed by this law for

advising or for enticing a slave

[Pg. 48]

to leave his master, or for harboring a fugitive, were a

fine, not to exceed five hundred dollars, and, at the

discretion of the court, imprisonment not to exceed

sixty days. In addition, the offender was to be

liable in an action at the suit of the party

injured.1 It can scarcely be supposed

that a state Fugitive Slave Law like this would

otherwise affect persons that were already engaged in

aiding runaways than to make them more certain than ever

that their cause was just.

The loss of slave property sustained by Southern

planters was not diminished, and the outcry of the South

for a more rigorous national law on the subject was by

no means hushed. In 1850 Congress met the case by

substituting for the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 the

measure called the second Fugitive Slave Law. The

penalties provided by this law were, of course, more

severe than those of the act of 1793. Any person

hindering the claimant from arresting the fugitive, or

attempting the rescue or concealment of the fugitive,

became "subject to a fine not exceeding one thousand

dollars, or imprisonment not exceeding six months," and

was liable for " civil damages to the party injured by

such illegal conduct in the sum of one thousand dollars

for each fugitive so lost." These provisions of

the new law only added fresh fuel to the fire. The

determination to prevent the recovery of escaped slaves

by their owners spread rapidly among the inhabitants of

the free states. Many of these persons, who had

hitherto refrained from acting for or against the

fugitive, were provoked into helping defeat the action

of a law commanding them "to aid and assist in the

prompt and efficient execution" of a measure that would

have set them at the miserable business of

slave-catching. Clay only expressed a wish

instead of a fact, when he maintained in 1851 that the

law was being executed in Indiana, Ohio and other

states. Another Southern senator was much nearer

the truth when he complained of the small number of

recaptures under the recent act.

The risk of suffering severe penalties by violating the

Fugitive Slave laws was less wearing, probably, on

abolitionists than was the social disdain they brought

upon themselves by acknowledging their principles.

During a generation or more

---------------

1 The date of the act is February 26, 1839.

[Pg. 49] - ABUSE SUFFERED BY

ABOLITIONISTS

they were in a minority in many

communities, and were forced to submit to the taunts and

insults of persons that did not distinguish between

abolition of slavery and fusion of the white and the

black races. "Black abolitionist," "niggerite,"

"amalgamationist" and "nigger thief " were convenient

epithets in the mouths of pro-slavery champions in many

Northern neighborhoods. The statement was not

uncommonly made about those suspected of harboring

slaves, that they did so from motives of thrift and

gain. It was said that some underground helpers

made use of the labor of runaways, especially in

harvest-time, as long as it suited their convenience,

then on the pretext of danger hurried the negroes off

without pay. Unreasoning malice alone could

concoct so absurd an explanation of a philanthropy

involving so much cost and risk.1

Abolitionists were often made uncomfortable in their

church relations by the uncomplimentary attentions they

received, or by the discovery that they were regarded as

unwelcome disturbers of the household of faith.2

Even the Society of Friends is not above the charge of

having lost sight, in some quarters, of the precepts of

Anthony Benezet and John Woolman.

Uxbridge monthly meeting is known to have disowned

Abby Kelly because she gave anti-slavery

lectures.3 The church certificate given

to Mrs. Elizabeth Buffum Chace when she

transferred her membership from Swanzey monthly meeting

to Providence (Rhode Island) monthly meeting was without

the acknowledgment usually contained in such

certificates that the bearer "was of orderly life and

conversation."4 A popular Hicksite

minister of New York City, in commending the fugitive

Thomas Hughes for consenting to return South

with his master, said, "I had a thousand times rather be

a slave, and spend my days with slaveholders, than to

dwell in companionship with abolitionists."5

In the Methodist Church

---------------

1 See an article entitled "An Underground Railway," by

Robert W. Carroll, of Cincinnati, O., in the

Cincinnati Times-Star, Aug. 19, 1890; also Smedley,

Underground Railroad, p. 182; and J. B. Robinson,

Pictures of Slavery and Anti-Slavery, pp. 293,

294.

2 History of Henry County, Indiana, p. 126,

et seq.

3 Elizabeth Buffum Chace,

Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, p. 19.

4 Ibid., p. 18.

5 Lydia Maria Child, Life of Isaac T. Hopper,

pp. 388, 389.

[Pg. 50]

there came to be such stress of

feeling between the abolitionists and the other members,

that in many places the former withdrew and organized

little congregations apart, under the denominational

name, Wesleyan Methodist. The truth is, the mass

of the people of the free states were by no means

abolitionists; they cherished an intense prejudice

against the negro, and permitted it to extend to all

anti-slavery advocates. They were willing to let

slavery alone, and desired that others should let it

alone. In the Western states the character of

public sentiment is evidenced by the fact that generally

the political party considered to be most favorable to

slavery could command a majority, and "black laws" were

framed at the behest of Southern politicians for the

purpose of making residence in the Northern states a

disagreeable thing for the negro.1

Abolitionists were frequently subjected to espionage;

the arrival of a party of colored people at a house

after daybreak would arouse suspicion and cause the

place to be closely watched; a chance meeting with a

neighbor in the highway would perhaps be the means by

which some abolitionists' secrets would become known.

In such cases it did not always follow that the

discovery brought ruin upon the head of the offender,

even when the discoverer was a person of pro-slavery

views. Nevertheless, accidents of the kind

described served to fasten the suspicions of a locality

upon the offender. Gravner and Hannah Marsh,

Quakers, living near Downington, in Chester County,

Pennsylvania, became known to their proslavery neighbors

as agents on the Underground Road. These neighbors

were not disposed to inform against them, although one

woman, intent on finding out how many slaves they aided

in a year, with much watching counted sixty.2

The Rev. John Cross, a Presbyterian

minister living in Elba Township, Knox County, Illinois,

about the year 1840, had neighbors that insisted on his

answering to the law for the help he gave to some

fugitives. Mr. Cross made no secret

of his principles and accordingly became game for his

enemies. One of these was Jacob Kightlinger,

who observed a wagon-load of

---------------

1 See President

Fairchild's pamphlet, The Underground Railroad.

2 Smedley, Underground

Railroad, p. 139

[Pg. 51] - ABOLITIONISTS UNDER

SURVEILLANCE

negroes being taken in the direction

of Mr. Cross's house. Investigation

by Mr. Kightlinger and several of his

friends proved their suspicions to be true, and by their

action Mr. Cross was indicted for

harboring fugitive slaves.1

Parties in pursuit of fugitives were compelled to make

careful and often long-continued search to find traces

of their wayfaring chattels. During such missions

they were, of course, inquisitive and vigilant, and when

circumstances seemed to warrant it, they set men to

watch the premises of the persons most suspicioned, and

to report any mysterious actions occurring within the

district patrolled. The houses of many noted

abolitionists along the Ohio River were frequently under

the surveillance of slave-hunters. It was not a

rare thing that towns and villages in regions adjacent

to the Southern states were terrorized by crowds of

roughs eager to find the hiding places of slaves,

recently missed by masters bent on their recovery. The

following extracts from a letter written by Mr.

William Steel to Mr. David

Putnam, Jr., of Point Harmar, Ohio, will

show the methods practised by slave-hunters when in

eager pursuit of fugitives: -

| |

|

WOODSFIELD, MONROE CO., O.

Sept. 5, 1843. |

DR. DAVID PUTNAM, JR.:

Dear Sir, - I received yours of the 26th ult.

and was very glad to hear from it that Stephen Quixot

had such good luck in getting his family from Virginia,

but we began to be very uneasy about them as we did not

hear from them again until last Saturday, . .

. . we then heard they were on the route leading

through Summerfield, but that the route from there to

Somerton was so closely watched both day and night for

some time past on account of the human cattle that have

lately escaped from Virginia, that they could not

proceed farther on that route. So we made an

arrangement with the Summerfield friends to meet them on

Sunday evening about ten miles west of this and bring

them on to this

route . . . the abolitionists of the west

part of this county have had very difficult work in

getting them all off without being caught, as the whole

of that part of the country has been filled with

Southern blood hounds upon their track, and some of the

aboli-

---------------

1 History of Konx County, Ill., pp.

213, 214. Mr. Kightlinger's account of this

affair is published under his own name.

[Pg. 52]

tionists' houses

have been watched day and night for several days in

succession. This evening a company of eight

Virginia hounds passed through this place north on the

hunt of some of their two legged chattels. . . .

Since writing the above I have understood that something

near twenty Virginians including the eight above

mentioned have just passed through town on their way to

the Somerton neighborhood, but I do not think they will

get much information about their lost chattels there. .

. .

| |

|

Yours for the

Slave,

WILLIAM STEEL1 |

A case that well illustrates the

method of search employed by pursuing parties is that of

the escape of the Nuckolls slaves through Iowa,

the incidents of which are still vivid in the memories

of some that witnessed them. Mr. Nuckolls,

of Nebraska City, Nebraska, lost two slave-girls in

December, 1858. He instituted search for them in

Tabor, an abolitionist centre, and did not neglect to

guard the crossings of two streams in the vicinity,

Silver Creek and the Nishnabotna River. As the

slaves had been promptly despatched to Chicago, this

search availed him nothing. A second and more

thorough hunt was decided on, and the aid of a score or

more fellows was secured. These men made entrance

into houses by force and violence, when bravado failed

to gain them admission.2 At one house

where the remonstrance against intrusion was unusually

strong the person remonstrating was struck over the head

and injured for life. The outcome of the whole

affair was that Mr. Nuckolls had some ten

thousand dollars to pay in damages and costs, and, after

all, failed to recover his slaves.3

Many were the inducements to practise espionage on

abolitionists.

Large sums were offered for the capture of fugitives,

and rewards were offered also for the arrest and

delivery

---------------

1 The original letter is in the possession

of the author of this book.

2 The Tabor Beacon, 1890 1891,

Chapter XXI of a series of articles by the Rev. John

Todd, on "The Early Settlement and Growth of Western

Iowa." Mr. Todd was one of the early settlers of

western Iowa. The letters were received from his

son, Professor James E. Todd, of the University of South

Dakota, Vermillion, S. Dak.

3 Letter of Mr. Sturgis Williams, Percival,

Ia., 1894. Mr. Williams was also one of the

pioneers of western Iowa.

[Pg. 53] - REWARDS FOR ABDUCTION OF

ABOLITIONISTS

south of Mason and Dixon’s line of

certain abolitionists, who were well-enough known to

have the hatred of many Southerners. “At an

anti-slavery meeting of the citizens of Sardinia and

vicinity, held on Nov. 21,1838, a committee of

respectable citizens presented a report, accompanied

with affidavits in support of its declarations, stating

that for more than a year past there had been an unusual

degree of hatred manifested by the slave-hunters and

slaveholders towards the abolitionists of Brown County,

and that rewards varying from $500 to $2,500 had been

repeatedly offered by different persons for the

abduction or assassination of the Rev. John B. Mahan;

and rewards had also been offered for Amos Pettijohn,

William A. Frazier and Dr. Isaac M. Beck,

of Sardinia, the Rev. John Rankin and Dr.

Alexander Campbell, of Ripley, William McCoy,

of Russellville, and citizens of Adams County."1

A resolution was offered in the Maryland Legislature, in

January, 1860, proposing a reward for the arrest of

Thomas Garrett, of Wilmington, for "stealing"

slaves.2 It is perhaps an evidence of

the extraordinary caution and shrewdness employed by

managers of the Road generally that so many of them

escaped without suffering the penalties of the law or

the inflictions of private vengeance.

Slave-owners occasionally tried to find out the secrets

of an underground station or of a route by visiting

various localities in disguise. A Kentucky

slaveholder clad in the Friends' peculiar garb went to

the house of John Charles, a Quaker of Richmond,

Indiana, and meeting a son of Mr. Charles

accosted him with the words, "Well, sir, my little

mannie, hasn't thee father gone to Canada with some

niggers?" Young Charles quickly perceived

the disguise, and pointing his finger at the man

declared him to be a "wolf in sheep's clothing."3

About the year 1840 there came into Cass County,

Indiana, a man from Kentucky by the name of Carpenter,

who professed to be an anti-slavery lecturer and an

agent for

---------------

1

History of Brown County, Ohio, p. 314

2 The New Reign of Terror in the

Slaveholding States, for 1859-1860 (Anti-Slavery

Tracts, No. 4, New Series), pp. 49. 50.

3 Letter of Mrs. Mary C. Thorne, Selma,

Clark Co., O., Mar. 3, 1892. John Charles was an

uncle of Mrs. Thorne

[Pg. 54]

certain anti-slavery papers. He

visited the abolitionists and seemed zealous in the

cause. In this way he learned the whereabouts of

seven fugitives that had arrived in the neighborhood

from Kentucky a few weeks before. He sent word to their

masters, and in due time they were all seized, but had

not been taken far before the neighborhood was aroused,

masters and victims were overtaken and carried to the

county-seat, and trial was procured, and the slaves were

again set free.

Thus the penalties of the law, the contempt of

neighbors, and the espionage of persons interested in

returning fugitives to bondage made secrecy necessary in

the service of the Underground Railroad.

Night was the only time, of course, in which the

fugitive and his helpers could feel themselves even

partially secure. Probably most slaves that

started for Canada had learned to known the north star,

and to many of these superstitious persons its light

seemed the enduring witness of the divine interest in

their deliverance. When clouds obscured the stars

they had recourse, perhaps, to such bits of homely

knowledge as, that in forests the trunks of trees are

commonly moss-grown on their north sides. In

Kentucky and western Virginia many fugitives were guided

to free soil by the tributaries of the Ohio; while in

central and eastern Virginia the ranges of the

Appalachian chain marked the direction to be taken.

After reaching the initial station of some line of

Underground Road reaching the initial station of some

line of Underground Road the fugitive found himself

provided with such accommodations for rest and

refreshment as circumstances would allow; and after an

interval of a day or more he was conveyed, usually in

the night, to the house of the next friend.

Sometimes, however, when a guide was thought to be

unnecessary the fugitive was sent on foot to the next

station, full and minute instructions for finding it

having been given him. The faltering step, and the

light, uncertain rapping of the fugitive at the door,

was quickly recognized by the family within, and the

stranger was admitted with a welcome at once sincere and

subdued. There was a suppressed stir in the house

while the fire was building and food preparing; and

after the hunger and chill of the wayfarer had been

dispelled, he was provided with a bed in some

out-of-the-way part of the

[Pg. 55] - MIDNIGHT SERVICE

house, or under the hay in the barn

loft, according to the degree of danger. Often a

household was awakened to find a company of five or more

negroes at the door. The arrival of such a company

was sometimes announced beforehand by special messenger.

That the amount of time taken from the hours of sleep

by underground service was no small item may be seen

from the following record covering the last half of

August, 1843. The record or memorandum is that of

Mr. David Putnam, Jr., of

Point Harmar, Ohio, and is given with all the

abbreviations:

| Aug. |

13/42 |

Sunday Morn. |

2 o'clock |

arrived |

| |

|

Sunday Eve. |

8½

" |

departed for

B. |

| |

16 |

Wednesday

Morn. |

2 " |

arrived |

| |

20 |

Sunday eve. |

10 " |

departed for

N. |

| Wife &

children |

21 |

Monday morn. |

2 " |

arrived from

B. |

| |

|

" eve. |

10 " |

left for Mr.

H. |

| |

22 |

Tuesday " |

11 " |

left for W. |

| A. L. & S. J. |

28 |

Monday morn.

|

1 " |

arrived left

2 o'clock.1 |

This is plainly a schedule of arriving

and departing “trains” on the Underground Road. It

is noticeable that the schedule contains no description,

numerical or otherwise, of the parties coming and going;

nor does it indicate, except by initial, to what places

or persons the parties were despatched; further, it does

not indicate whether Mr. Putnam

accompanied them or not. It does, however, give us

a clue to the amount of night service that was done at a

station of average activity on the Ohio River as early

as the year 1848. The demands upon operators

increased, we know, from this time on till 1860.

The memorandum also shows the variation in the length of

time during which different companies of fugitives were

detained at a station; thus, the first fugitive, or

company of fugitives, as the case may have been,

departed on the evening of the day of arrival; the

second party was kept in concealment from Wednesday

morning until the Sunday night next following before it

was sent on its way; the third

---------------

1 The

original memorandum is written in pencil on a letter

received by Mr. Putnam from Mr. John Stone, of Belpre,

O., in Aug., 1843. The contents of this letter, or

message, is given on page 57. The original is in

possession of the author.

[Pg. 56]

party seems to have been divided, one

section being forwarded the night of the day of arrival,

the other the next night following; in the case of the

last company there seems to have existed some especial

reason for haste, and we find it hurried away at two

o’clock in the morning, after only an hour’s

intermission for rest and refreshment. The

memorandum of night service at the Putnam station may be

regarded as fairly representative of the night service

at many other posts or stations throughout Ohio and the

adjoining states.

Much of the communication relating to fugitive slaves

was had in guarded language. Special signals,

whispered conversations, passwords, messages couched in

figurative phrases, were the common modes of conveying

information about underground passengers, or about

parties in pursuit of fugitives. These modes of

communication constituted what abolitionists knew as the

“ grape-vine telegraph.”1 The signals

employed were of various kinds, and were local in usage.

Fugitives crossing the Ohio River in the vicinity of

Parkersburg, in western Virginia, were sometimes

announced at stations near the river by their guides by

a shrill tremolo-call like that of the owl.

Colonel John Stone and Mr.

David Putnam, Jr., of Marietta, Ohio,

made frequent use of this signal.2

Different neighborhoods had their peculiar combinations

of knocks or raps to be made upon the door or window of

a station when fugitives were awaiting admission.

In Harrison County, Ohio, around Cadiz, one of the

recognized signals was three distinct but subdued

knocks. To the in-

---------------

1 The

Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888,

p. 20; also letter of S. J. Wright, Rushville,

O., Aug. 29, 1894, and letter of Ira Thomas, Springboro,

O., Oct. 29, 1895.

2 This owl signal was mentioned in

conversation with several residents of Marietta.

Miss Martha Putnam says she has heard her father make

the “hoot-owl ” call hundreds of times. General R.

R. Dawes designates this call the “river signal.”

“When I was a hoy of eight,” he says, “I was visiting my

grandfather, Judge Ephraim Cutler.

The place was called Constitution. Somehow, in the

night I was wakened up, and a wagon came down over the

hill to the river. Then a call was given, a

hoot-owl call, and this was answered by a similar one

from the other side; then a boat went out

and brought over the crowd. My mother got out of

bed and kneeled down and prayed for them, and had me

kneel with her.” Conversation with General

Dawes, Marietta, O., Aug. 21, 1892.

[Pg. 57] - MESSAGES

|

quiry, "Who's there?"

the reply was, "a friend with friends."1

Passwords were used on some sections of the

Road. The agents at York in

southeastern Pennsylvania made use of them,

and William Yokum, a constable of the

town, who was kindly disposed towards

runaways, was able to be most helpful in

times of emergency by his knowledge of the

watchwords, one of which was "William

Penn."2 Messages

couched in figurative language were often

sent. The following note, written by

Mr. John Stone, of Belpre, Ohio, in

August, 1843, is a good example: -

BELPRE Friday Morning

DAVID PUTNAM

Business is aranged for

Saturday night be on the lookout and if

practicable let a carriage come & meet the

carawan.

J. S.3

Mr. I. Newton Peirce forwarded a

number of fugitives from Alliance, Ohio, to

Cleveland, over the Cleveland and Western

Railroad. He sent with each company a

note to a Cleveland merchant, Mr. Joseph

Garretson, saying: "Please forward

immediately the U. G. baggage this day sent

to you. Yours truly, I. N. P."4

Mr.

---------------

1 Letter of the Rev. J. B. Lee, Franklinville,

N.Y., Oct. 21, 1895.

2 Smedley, Underground Railroad, p. 46

3 See the facsimile.

4 Letter of I. Newton Peirce, Folcroft, Sharon Hill

P.O., Delaware Co., Pa., Feb. 1, 1893. |

[Pg. 58]

G. W. Weston, of Low Moor,

Iowa, was the author of similar communications addressed

to a friend, Mr. C. B. Campbell, of Clinton.

MR. C. B. C.,

Dear Sir: - By tomorrow evening's mail, you

will receive two volumes of the "Irrepressible

Conflict" bound in black. After perusal,

please forward, and oblige,

The Hon.

Thomas Mitchell, founder of Mitchellville, near Des

Moines, Iowa, forwarded fugitives to Mr. J. B.

Grinnell, after whom the town of Grinnell was

named. The latter gives the following note as a

sample of the messages that passed between them: -

Dear

Grinnell: - Uncle Tom says if the

roads are not too bad you can look for those fleeces of

wool by tomorrow. Send them on to test the market

and price, no back charges.

There were

many persons engaged in underground work that did not

always take the precaution to veil their communications.

Judge Thomas Lee, of the Western Reserve, was one

of this class, as the following letter to Mr.

Putnam, of Point Harmar, will show: -

| |

|

CADIZ, OHIO,

March 17th, 1847. |

MR. DAVID PUTNAM,

Dear Sir: - I

understand you are a friend to the poor and are willing

to obey the heavenly mandate," Hide the outcases, betray

not him that wandereth." Believing this, and at

the request of Stephen Fairfax (who has been

permitted in divine providence to enjoy for a few days

the kind of liberty which Ohio gives to the man of

colour), I would be glad if you could find out and let

me know by letter what are the prospects if any.

---------------

1 History of Clinton County, Iowa,

article on the "Underground Railroad," pp. 413-416.

2 J. B. Grinnell, Men and Events of Forty

Years, p. 217.

[Pg. 59] - CONVEYANCE OF FUGITIVES

and. the probable time when, the

balance of the family will make the same effort to

obtain their inalienable right to life, liberty, and the

pursuit of happiness. Their friends who have gone

north are very anxious to have them follow, as they

think it much better to work for eight or ten dollars

per month than to work for nothing.

Yours in behalf of the millions of poor, opprest and

downtrodden in our land.

In the

conveyance of fugitives from station to station there

existed all the variety of method one would expect to

find. In the early days of the Underground Road

the fugitives were generally men. It was scarcely

thought necessary to send a guide with them unless some

special reason for so doing existed. They were,

therefore, commonly given such directions as they needed

and left to their own devices.) As the number of

refugees increased, and women and children were more

frequently seen upon the Road, and pursuit was more

common, the practice of transporting fugitives on

horseback, or by vehicle, was introduced. The

steam railroad was a new means furnished to

abolitionists by the progress of the times, and used by

them with greater or less frequency as circumstances

required, and when the safety of passengers would not be

sacrificed.

When fugitive travellers afoot or on horseback found

themselves pursued, safety lay in flight, unless indeed

the company was large enough, courageous enough, and

sufficiently well armed to give battle. The safety of

fugitives while travelling by conveyance lay mainly in

their concealment, and many were the stratagems

employed. Characteristic of the service of the

Underground Railroad were the covered wagons, closed

carriages and deep-bedded farm-wagons that hid the

passengers. There are those living who remember

special day-coaches of more peculiar construction.

Abram Allen, a Quaker of Oakland, Clinton

County, Ohio, had a large three-seated wagon, made for

the purpose of carrying fugitives. He called it

the Liberator. It was curtained all around, would

hold eight or ten persons, and had a mechanism with a

bell, invented by Mr. Allen, to

[Pg. 60]

record the number of miles travelled.1

A citizen of Troy, Ohio, a bookbinder by trade, had a

large wagon, built about with drawers in such a way as

to leave a large hiding-place in the centre of the

wagon-bed. As the bookbinder drove through the

country he found opportunity to help many a fugitive on

his way to Canada.2 Horace

Holt, of Rutland, Meigs County, Ohio, sold reeds to

his neighbors in southern Ohio. He had a box-bed

wagon with a lid that fastened with a padlock. In

this he hauled his supply of reeds; it was well

understood by a few that he also hauled fugitive slaves.3

Joseph Sider, of southern Indiana, found

his pedler wagon well adapted to the transportation of

slaves \ from Kentucky plantations.4

William Still gives instances of negroes

being placed in boxes, and shipped as freight by boat,

and also by rail, to friends in the North.

William Box Peel Jones was

boxed in Baltimore and sent to Philadelphia by way of

the Ericsson line of steamers, being seventeen hours on

the way.5 Henry Box Brown had

the same thrilling and perilous experience. His

trip consumed twenty-four hours, during which time he

was in the care of the Adams Express Company in transit

from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia.6

Abolitionists that drove wagons or carriages containing

refugees, “conductors” as they came to be called in the

terminology of the Railroad service, generally took the

precaution to have ostensible reasons for their

journeys. They sought to divest their excursions

of the air of mystery by seeming to be about legitimate

business. Hannah Marsh, of Chester

County, Pennsylvania, was in the habit of taking

---------------

1 Judge R. B.

Harlan and others, History of Clinton County, Ohio, pp.

380-383; letter of Seth Linton, Oakland, Clinton County,

O., Sept. 4, 1892; Smedley, Underground Railroad, p.

187.

2 The Miami Union, April 10,1895,

article entitled “A Reminiscence of Slave Times.”

3 Letter of Mrs. C. Grant, Pomeroy, Meigs

Co., O.

4 The Republican Leader, Mar. 16,

1894, article, “ Reminiscence of the Underground

Railroad,” by E. H. Trueblood.

5 See Underground Railroad Records,

pp. 46, 47.

6 Ibid., pp. 81-84; see also

Narrative of Henry Box Brown, who escaped from slavery

enclosed in a box 3 feet long and 2 wide, written from a

statement of facts made by himself, 1849, by Charles

Stearns.

[Pg. 61] - CONVEYANCE OF FUGITIVES

[Pg. 62]

[Pg. 63] - HIDING-PLACES

[Pg. 64]

woods; and afterwards in a rail pen

covered with straw.1 Eli F. Brown,

of Amesville, Athens County, Ohio, writes: "I

built an addition to my house in which I had a room with

its partition in pannels. One pannel could be

raised about a half inch and then slid back, so as to

permit a man to enter the room. When the pannel

was in place it appeared like its fellows . . . .

In the abutment of Zanesville bridge on the Putnam side

there was a place of concealment prepared."2

"Conductors" Levi Coffin, Edward

Harwood, and W. H. Brisbane, of Cincinnati,

Ohio, had a number of hiding-places for slaves.

"One was in the dark cellar of Coffin's store;

another was at Mr. Coffin's out-of-the-way

residence between Avondale and Walnut Hills; another was

a dark sub-cellar under the rear part of Dr. Bailey's

residence, corner of Sixth and College Streets."3

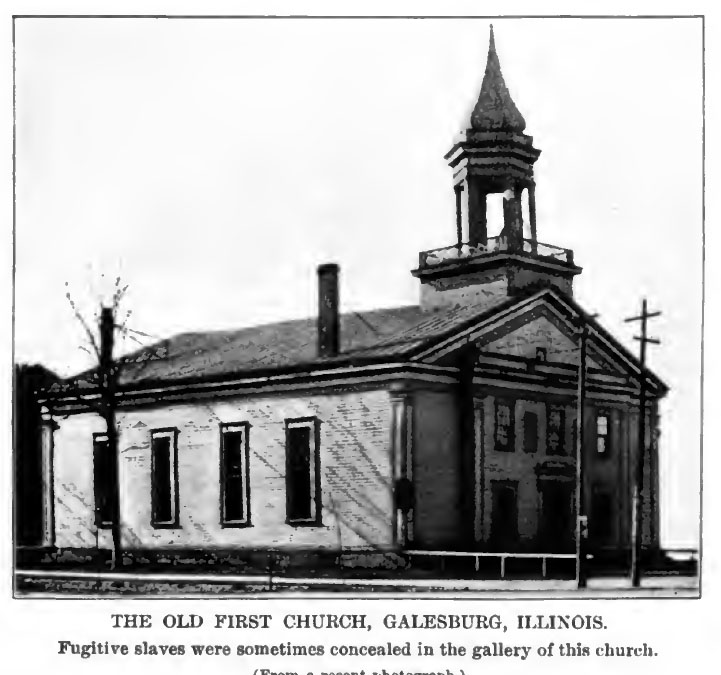

The gallery of the old First Church at Galesburg,

Illinois, was utilized as a place of concealment for

refugees by certain members of that church.4

Gabe N. Johnson, a colored man from Ironton, on

the Ohio River, sometimes hid fugitives in a coal-bank

back of his house.5 This list of

illustrations could be almost indefinitely continued.

A sufficient number has been given to show the ingenuity

necessarily used to secure safety.

In the transit from station to station some simple

disguise was often assumed. Thomas Garrett,

a Quaker of Wilmington, Delaware, kept a quantity of

garden tools on hand for this purpose. He

sometimes gave a man a scythe, rake, or some other

implement to carry through town. Having reached a

certain bridge on the way to the next station, the

pretending laborer concealed his tool under it, as he

had been directed, and journeyed on. Later the

tool was taken back to Mr. Garrett's to be used

for a similar purpose.6 Valentine

Nicholson, a station-keeper at Harveysburg, Warren

County,

---------------

1 Letter of

E. H. Trueblood, Hitchcock, Ind.

2 Letter of E. F. Brown, Amesville, O.

3 Cincinnati Commercial Gazette, Feb.

11, 1894, article by W. Eldebe.

4 Letter of Professor George Churchill,

Galesburg, Jan. 29, 1896.

5 Conversation with Gabe N. Johnson,

Ironton, O., Sept. 30, 1894.

6 Smedley, Underground Railroad, p.

242.

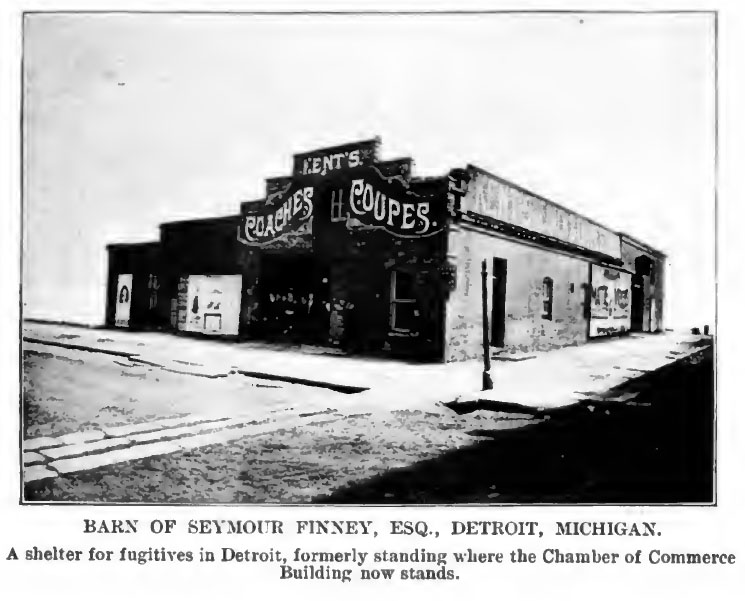

BARN OF SEYMOUR FINNEY,

ESQ., DETROIT, MICHIGAN,

A Shelter for fugitives in Detroit, formerly standing

where the Chamber of Commerce Building now stands.

THE OLD FIRST CHURCH,

GALESBURG, ILLINOIS

Fugitive slaves were sometimes concealed in the gallery

of this church.

(From a recent photograph)

[Pg. 65] - DISGUISES

[Pg. 66]

[Pg. 67] - LACK OF FORMAL

ORGANIZATION

Harper’s Ferry by resorting to similar

means.1 Among the Quakers the woman’s

costume was a favorite disguise for fugitives. No

one attired in it was likely to be in the least degree

suspicioned of being anything else than what the garb

proclaimed. The veiled bonnet also was peculiarly

adapted to conceal the features of the person disguised.2

One incident will suffice to show the utility of the

Quaker costume. One evening Joseph G. Walker,

a Quaker of Wilmington, Delaware, was appealed to by a

slave-woman, who was closely pursued. She was

permitted to enter Mr. Walker’s house, and

a few minutes later, in the gown and bonnet of Mrs.

Walker, she passed out of the front door leaning

upon the arm of the shrewd Quaker.3

It is quite apparent that the Underground Railroad was

not a formal organization with officers of different

ranks, a regular membership, and a treasury from which

to meet expenses. A terminology, it is true,

sprang up in connection with the work of the Road, and

one hears of station-keepers, agents, conductors, and

even presidents of the Underground Railroad; but these

titles were figurative terms, borrowed with other

expressions from the convenient vocabulary of steam

railways; and while they were useful among abolitionists

to save circumlocution, they commended themselves to the

friends of the slave by helping to mystify the minds of

the public. The need of organization was not felt

except in a few localities. It was only in towns

and cities that the distinctions of “managers,”

“contributing members,” and “agents” began to develop in

any significant way, and even in the case of these

places the distinctions must not be pushed far, for they

indicate merely that certain men by their sagacious

activity came to be called “managers,” while others less

bold, the contributing members, were willing to give

money towards defraying the expenses of some trusty

person, the agent, who would run the risk of piloting

fugitives.

The first reference to an organization devoted to the

busi-

---------------

1 Reminiscences of

Levi Coffin, pp. 439-442.

2 M. G. McDougall, Fugitive Slaves, p. 61.

3 Smedley, Underground Railroad, p. 244.

[Pg. 68]

[Pg. 69] - LACK OF FORMAL

ORGANIZATION

[Pg. 70]

[Pg. 71] - COMMITTEES OF VIGILANCE

agents or conductors was caused by the

large number of fugitives arriving at these points, and

the extreme caution necessary. When, at length,

indignation was aroused in the minds of Northern

abolitionists by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law,

Sept. 18, 1850, the determination to resist this measure

displayed itself in certain localities in the formation

of vigilance committees. Theodore Parker

explains that it was in consequence of the enactment of

this measure that "people held indignant meetings, and

organized committees of vigilance whose duty was to

prevent a fugitive from being arrested, if possible, or

to furnish legal aid, and raise every obstacle to his

rendition. The vigilance committees," he says,

"were also the employees of the U. G. R. R. and

effectively disposed of many a casus belli by

transferring the disputed chattel to Canada.

Money, time, wariness, devotedness for months and years,

that cannot be computed, and will never be recorded,

except, perhaps, in connection with cases whose details

had peculiar interest, was nobly rendered by the true

anti-slavery men."1 Such committees of

vigilance were organized in Syracuse, New York, Boston,

Springfield and some of the smaller towns of

Massachusetts, in Philadelphia and other places.

New York City, like Philadelphia, had a Vigilance

Committee as early as 1838. About this association

of the metropolis there is scarcely any information.2

We must be content then to confine our attention to the

committees called into existence by the Fugitive Slave

Law of 1850.

Eight days after the enactment of this law citizens of

Syracuse, New York, issued a call through the newspapers

for a public meeting, and on October 4 members of all

parties crowded the city-hall to express their censure

of the law. The meeting recommended "the

appointment of a Vigilance Committee of thirteen

citizens, whose duty it shall be to see that no person

is deprived of his liberty without 'due process of law.'

And all good citizens are earnestly requested to aid

---------------

1 Weiss, Life and

Correspondence of Theodore Parker, Vol. II, pp. 92,

93.

2 Frederick Douglass

relates that when he escaped from Maryland to New York,

in 1838, he was befriended by David Ruggles, the

secretary of the New York Vigilance Committee; Life

of Frederick Douglass, 1881, p. 205.

[Pg. 72]

[Pg. 73] - BOSTON COMMITTEE OF

VIGILANCE

[Pg. 74]

necessary, and he formed, therefore,

the League of Gileadites to resist systematically the

eforcement of the law. The name of this order was

significant in that it contained a warning to those of

its members that should show themselves cowards.

"Whosoever is fearful or afraid let him return and

depart early from Mount Gilead."1 In

the "Agreement and Rules" that Brown drafted for the

order, adopted Jan. 15, 1851, the following directions

for action were laid down: "Should one of your

number be arrested, you must collect together as quickly

as possible, so as to outnumber your adversaries . . . .

Let no able bodied man appear on the ground unequipped,

or with his weapons exposed to view. . . . Your plans

must be known only to yourselves and with the

understanding that all traitors must die, wherever

caught and proven to be guilty. . . . Let the

first blow be the signal for all to engage, . . . make

clean work with your enemies, and be sure you meddle not

with any others. . . . After effecting a rescue, if you

are assailed, go into the houses of your most prominent

and influential white friends with your wives, and that

will effectually fasten upon them the suspicion of being

connected with you, and will compel them to make a

common cause with you. . . . You may make a tumult

in the court-room where a trial is going on by burning

gunpowder freely in paper packages. . . . But in

such case the prisoner will need to take the hint at

once and bestir himself; and so should his friends

improve the opportunity for a general rush. . . .

Stand by one another and by your friends while a drop of

blood remains; and be hanged, if you must, but tell no

tales out of school. Make no confession." By

adopting the Agreement and Rules forty-four colored

persons constituted themselves "a branch of the United

States League of Gileadites," and agreed "to have no

officers except a treasurer and secretary pro tem.,

until after some trial of courage," when they could

choose officers on the basis of "courage, efficiency,

and general good conduct."2 Doubtless

the Gileadites of Springfield

---------------

1 Judg. vii. 3; Deut. xx.8; referred to by

Brown in his "Agreement and rules."

2 F. B. Sanborn, in his Life and Letters

of John brown, pp. 125, 126.

WILLIAM STILL,

Chairman of the Acting Vigilance Committee in

Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania, 1852-1860

[Pg. 75] - PHILADELPHIA COMMITTEES

OF VIGILANCE

did efficient service, for it appears

that the importance of the town as a way-station on the

Underground Road increased after the passage of the

Fugitive Slave Bill.1

We have already learned that Philadelphia had a

Vigilance Committee before 1840. In a speech made

before the meeting that organized the new committee,

Dec. 2, 1852, Mr. J. Miller McKim, the secretary

of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, gave the

reason for establishing a new committee. He said

that the old committee "had become disorganized and

scattered, and that for the last two or three years the

duties of this department had been performed by

individuals on their own responsibility, and sometimes

in a very irregular manner." It was accordingly

decided to form a new committee, called the General

Vigilance Committee, with the chairman and treasurer;

and within this body an Acting Committee of four

persons, "who should have the responsibility of

attending to every case that might require their aid, as

well as the exclusive authority to raise the funds

necessary for their purpose." The General

Committee comprised nineteen members, and had as its

head Mr. Robert Purvis, one of the signers of the

Declaration of Sentiments of the American Anti-Slavery

Society, and the first president of the old committee.

The Acting Committee had as its chairman William

Still, a colored clerk in the office of the

Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society and a most energetic

underground helper. The Philadelphia Vigilance

Committee, thus constituted, continued intact until

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation.2.

Some insight into the work accomplished by the Acting

Committee can be obtained by an examination of the book

compiled by William Still under the title

Underground Railroad Records. The Acting

Committee was required to keep a record of all its

doings. Mr. Still's volume was evidently

amassed by the

---------------

gives the agreement, rues, and signatures.

See also R. J. Hinton's John Brown and His Men,

Appendix, pp. 585, 588.

1 Mason A. Green, History of Springfield,

Massachusetts, 1636-1886, p. 506.

2 Article, "Meeting to Form a Vigilance

Committee," in the Pennsylvania Freeman, Dec. 9,

1852; quoted in the Underground Railroad Records,

by William Still, pp. 610-612

[Pg. 76]

transcription of many of the incidents

that found their way under this order into the archives

of the committee. The work was limited to the

assistance of such needy fugitives as came to

Philadelphia; and was not extended, except in rare

cases, to inciting slaves to run away from their

masters, or to aiding them in so doing.1

The relief of the destitution existing among the

wayworn travellers was a matter requiring considerable

outlay of time and money on the part of abolitionists.

There was occasionally a fugitive or family of

fugitives, that, having better opportunity or possessing

greater foresight than others, made provision for the

journey and escaped to Canada with little or no

dependence on the aid of underground operators.

Asbury Parker, of Ironton, Ohio, fled from

Greenup County, Kentucky, in 1857, clad in a suit of

broadcloth, alone befitting, as he thought, the dignity

of a free man.2

The brother of Anthony Bingey, of Windsor,

Ontario, came unexpectedly into the possession of five

hundred dollars. With this money he instructed a

friend in Cincinnati to procure a team and wagon to

convey the family of Bingey to Canada. The

com pany arrived at Sandusky after being only three days

on the road.3

But the mass of fugitives were thinly clad, and had

only such food as they could forage until they reached

the Under ground Railroad. The arrival of a

company at a station would be at once followed by the

preparation, often at midnight, of a meal for the

pilgrims and their guides. It was a common thing

for a station to entertain a company of five or six; and

companies of twenty-eight or thirty are not unheard of

Levi Coffin says, “The largest company of

slaves ever seated at our table, at one time, numbered

seventeen.”4

During one month in the year 1854 or 1855 there were

sixty runaways at the house of Aaron L. Benedict,

a station in the Alum-

---------------

1 Still's

Underground Railroad Records, p. 177.

References to the action of the committee of which

Mr. Still was chairman will be found scattered

through the Records. See, for example, pp.

70, 98, 102, 131, 150, 162, 173, 176, 204, 224, 274,

275, 303, 325, 335, 388, 412, 449, 493, 500.

2 Conversation with Asbury Parker, Ironton,

O., Sept. 30 1894.

3 Conversation with Anthony Bingey, Windsor,

Ont. July 3, 1895.

4 Reminiscenses, p. 178

[Pg. 77] - SUPPLIES FOR PASSENGERS

Creek Quaker Settlement in central

Ohio. On one occasion twenty sat down to dinner in

Mr. Benedict’s house.1

It will thus be seen

that the supply of provisions alone was for the average

station-keeper no inconsiderable item of expense, and

that it was one involving much labor.

The arrangements for furnishing fugitives with

clothing, like much of the underground work done at the

stations, came within the province of the women of the

stations., While the noted fugitive. William

Wells Brown, lay sick at the house of his

benefactor, Mr. Wells Brown, in southwestern

Ohio, the family made him some clothing, and Mr.

Brown purchased him a pair of boots.2

Women’s anti-slavery societies in many places conducted

sewing-circles, as a branch of their work, for the

purpose of supplying clothes and other necessities to

fugitives. The Woman’s Anti-Slavery Society of

Ellington, Chautauqua County, New York, sent a letter to

William Still, Nov. 21, 1859, saying:

“Every year we have sent a box of clothing, bedding,

etc., to the aid of the fugitive, and wishing to send it

where it would be of the most service, we have it

suggested to us, to send to you the box we have at

present. You would confer a favor . . . by writing

us, . . . whether or not it would be more advantageous

to you than some nearer station. . . .”3

The Women's Anti-Slavery Sewing Society of Cincinnati

maintained an active interest in underground work going

on in their city by supplying clothing to needy

travellers.4 The Female Anti-Slavery

Association of Henry County, Indiana, organized a

Committee of Vigilance in 1841 "to seek out such colored

females as are not suitably provided for, who may now

be, or who shall hereafter come, within our limits, and

assist them in any way they may deem expedient, either

by advice or pecuniary means. . . ."5

---------------

1.

Conversation with M. J. Benedict, Alum Creek

Settlement, Dec. 2, 1893. See also Underground

Railroad, Smedley, pp. 56, 136, 142, 174.

2 Narrative of William W. Brown, A

Fugitive Slave, written by himself, 2d ed., 1848, p.

102.

3. The letter is printed in full, together

with others letters, in Still's Underground Railroad

Records,pp. 590, 591.

4 Levi Coffin, Reminiscences, p. 316.

5 Protectionist, Arnold Buffum,

Editor, New Garden, Ind., 7th mo., 1st 1841.

[Pg. 78]

In some of

the large centres, money as well as clothing and food

was constantly needed for the proper performance of the

underground work. Thus, for example, at

Cincinnati, Ohio, it was frequently necessary to hire

carriages in which to convey fugitives out of the city

to some neighboring station. From time to time as

the occasion arose Levi Coffin collected

the funds needed for such purposes from business

acquaintances. He called these contributors

“stock-holders ” in the Underground Railroad.1

After steam railroads be came incorporated in the

underground system money was required at different

points to purchase tickets for fugitives. The

Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia defrayed the

travelling expenses of many refugees in sending some to

New York City, some to Elmira and a few to Canada.2

Frederick Douglass, who kept a station at

Rochester, New York, received contributions of money to

pay the railroad fares of the fugitives he forwarded to

Canada and to give them a little more for pressing

necessities.3

The use of steam railroads as a means of transportation

of this class of passengers began with the completion of

lines of road to the lakes. This did not take

place till about 1850. It was, therefore, during

the last decade of the history of the Underground Road

that surface lines, as they were some times called by

abolitionists, became a part of the secret system.

There were probably more surface-lines in Ohio than in

any other state. The old Mad River Railroad, or

Sandusky, Dayton and Cincinnati Railroad, of western

Ohio, (now a part of the “Big Four” system), began to be

used at least as early as 1852 by instructed fugitives.4

The Sandusky, Mansfield and Newark Railroad

(now the Baltimore and Ohio) from Utica, Licking County,

Ohio, to Sandusky, was sometimes used by the same class

of persons.5 After

---------------

1

Reminiscences, pp. 317, 321.

2 Still’s Underground Railroad Records, p. 613.

3 Ibid., p. 598. In the fragment of a

letter from which Mr. Still quotes, Mr. Douglass says,

“They [the fugitives] usually tarry with us only during

the night, and are forwarded to Canada by the morning

train. We give them supper, lodging, and

breakfast, pay their expenses, and give them a

half-dollar over.”

4 The Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888,

p. 21.

5 Ibid., pp. 23, 57, 79.

[Pg. 79] - TRANSPORTATION OVER

STEAM RAILROADS

the construction of the Cleveland,

Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad1 as far as

Greenwich in northern Ohio, fugitives often came to that

point concealed in freight-cars. In eastern Ohio

there were two additional routes by rail sometimes

employed in underground traffic: one of these appears to

have been the Cleveland and Western Canton from

Zanesville north,2 and the other was the

Cleveland and Western between Alliance and Cleveland.3

In Indiana the Louisville, New Albany and Chicago

Railroad from Crawfordsville northward was patronized by

underground travellers until the activity of

slave-hunters caused it to be abandoned.4

Fugitives were sometimes transported across the State of

Michigan by the Michigan Central Railroad. In

Illinois there seems to have been not less than three

railroads that carried fugitives: these were the

Chicago, Burlington and Quincy,5 the Chicago

and Rock Island6 and the Illinois Central.7

When John Brown made his famous journey through

Iowa in the winter of 1858-1859 he shipped his company

of twelve fugitives in a stock car from West Liberty,

Iowa, to Chicago, by way of the Chicago and Rock Island

route.8 In Pennsylvania and New York

there were several lines over which runaways were sent

when circumstances permitted. At Harrisburg,

Reading and other points along the Philadelphia and

Reading Railroad, fugitives were put aboard the cars for

Philadelphia.9 From Pennsylvania they

were forwarded

---------------

1 Ibid.,

p. 74. The "Tree C's" is now the Cleveland,

Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad, or "Big

Four" Route.

2 Conversation with Thomas Williams of

Pennsville, O.; letter of H. C. Harvey, Manchester,

Kan., Jan. 16, 1893.

3 Letter of I. Newton Peirce, Folcroft, Pa.,

Feb. 1, 1893.

4 Letter of Sidney Speed, Crawfordsville,

Ind., Mar. 6, 1896. Mr. Speed and his father were

both connected with the Crawfordsville centre.

5 Life and Poems of John Howard Bryant,

p. 30; letter of William H. Collins, Quincy, Ill.,

Jan. 13, 1896; History of Knox County, Illinois,

p. 211.

6 Letter of George L. Burroughes, Cairo,

Ill., Jan. 6, 1896.

7 Ibid.; conversation with the Rev.

R. G. Ramsey, Cadiz, O., Aug. 18, 1892.

8 J. B. Grinell, Men and Events of Forty

Years, p. 216.

9 Smedley, Underground Railroad, pp.

174, 176, 177, 365. The following letter is in

point: -

"SCHUYLKILL, 22th Mo., 7th, 1857.

WILLIAM STILL, Respected Friend: - There

are three colored friends at my house now, who will

reach the city by the Philadelphia and Reading train

this evening. Please meet them.

Thine, etc.,

E. F. PENNYPACKER."

[Pg. 80]

by the Vigilance Committee over

different lines, sometimes by "way of the Pennsylvania

Railroad to New York City; sometimes by way of the

Philadelphia and Reading and the Northern Central to

Elmira, New York, whence they were sent on by the same

line to Niagara Falls. Fugitives put aboard the

cars at Elmira were furnished with money from a fund

provided by the anti-slavery society. As a matter

of precaution they were sent out of town at four o’clock

in the morning, and were always placed by the train

officials, who knew their destination, in the

baggage-car.1 The New York Central

Railroad from Rochester west was an outlet made use of

by Frederick Douglass in passing slaves to

Canada. At Syracuse, during several years before

the beginning of the War, one of the directors of this

road, Mr. Horace White, the father

of Dr. Andrew D. White, distributed passes to

fugitives. This fact did not come to the knowledge

of Dr. White until after his father’s demise.

He relates: “Some years after . . . I met an old

‘abolitionist’ of Syracuse, who said to me that he had

often come to my father’s house, rattled at the windows,

informed my father of the passes he needed for fugitive

slaves, received them through the window, and then

departed, nobody else being the wiser. On my

asking my mother, who survived my father several years,

about it, she said: ‘Yes, such things frequently

occurred, and your father, if he was satisfied of the

genuineness of the request, always wrote off the passes

and handed them out, asking no questions.”2

In the New England states fugitives travelled, under

the instruction of friends, by way of the Providence and

Worcester Railroad from Valley Falls, Rhode Island, to

Worcester, Massachusetts, where by arrangement they were

transferred to the Vermont Road.3 The

Boston and Worcester Railroad between Newton and

Worcester, Massachusetts, as also between Boston and

Worcester, seems to have been used to some extent in

this way.4 The Grand Trunk, extending

from Port-

---------------

1 Letter of

John W. Jones, Elmira, N.Y., Jan. 18, 1897.

2 Letter of the Hon. Andrew D. White,

Ithaca, N. Y., Apr. 10, 1897.

3 Mrs. Elizabeth Buffum Chace,

Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, pp. 28, 38.

4 Letter of William I. Bowditch, Boston,

Apr. 5, 1893. Mr. Bowditch says: "Generally I

passed them (the fugitivs) on to William Jackson, at

[Pg. 81] - TRAFFIC BY WATER

land, Maine, through the northern

parts of New Hampshire and Vermont into Canada,

occasionally gave passes to fugitives, and would always

take reduced fares for this class of passengers.1

The advantages of escape by boat were early discerned

by slaves living near the coast or along inland rivers.

Vessels engaged in our coastwise trade became more or

less involved in transporting fugitives from Southern

ports to Northern soil. Small trading vessels,

returning from their voyages to Norfolk and Portsmouth,

Virginia, landed slaves on the New England coast.2

In July, 1853, the brig Florence (Captain

Amos Hopkins, of Hallowell, Maine) from

Wilmington, North Carolina, was required, while lying in

Boston harbor, to surrender a fugitive found on board.

In September, 1854, the schooner Sally Ann

(of Belfast, Maine), from the same Southern port, was

induced to give up a slave known to be on board.

In October of the same year the brig Cameo (of Augusta,

Maine) brought a stowaway from Jacksonville, Florida,

into Boston harbor, and, as in the two preceding cases,

the slave was rescued from the danger of return to the

South through the activity and shrewdness of Captain

Austin Bearse, the agent of the Vigilance

Committee of Boston.3 The son of a

slaveholder living at Newberne, North Carolina,

forwarded slaves from that point to the Vigilance

Committee of Philadelphia on vessels engaged in the

lumber trade.4 In November, 1855,

Captain Fountain brought twenty-one fugitives

concealed on his vessel in a cargo of grain from

Norfolk, Virginia, to Philadelphia.5

The tributaries flowing into the Ohio River from

Virginia and Kentucky furnished convenient channels of

escape for

---------------

Newton. His house being on the Worcester

Railroad, he could easily forward any one."

Captain Austin Bearse, Reminiscences of

Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston, p. 37.

1 Letter of

Brown Thurston, Portland, Me., Oct. 21, 1895.

2 Mrs. Elizabeth Buffum Chace,

Anti-Slavery Reminiscences, pp. 27, 30.

3 Austin Bearse, Reminiscences of

Fugitive-Slave Law Days in Boston, 1880, pp. 34-39.

4 Smedley, Underground Railroad,

letter of Robert Purvis, of Philadelphia, p. 335.

5 Still, Underground Railroad Records,

pp. 165-172. For other cases, see pp. 211,

379-381, 437, 558, 559-565.

[Pg. 82]

many slaves. The concurrent

testimony of abolitionists living along the Ohio is to

the effect that streams like the Kanawha River bore many

a boat-load of fugitives to the southern boundary of the

free states. It is not a mere coincidence that a

large number of the most important centres of activity

lie along the southern line of the Western free states

at points near or opposite the mouths of rivers and

creeks. On the Mississippi, Ohio and Illinois

rivers north-bound steamboats not infrequently provided

the means of escape. Jefferson Davis

declared in the Senate that many slaves escaped from his

state into Ohio by taking passage on the boats of the

Mississippi.1

Abolitionists found it desirable to have waterway

extensions of their secret lines. Boats, the

captains of which were favorable, were therefore drafted

into the service when running on convenient routes.

Boats plying between Portland, Maine, and St. John, New

Brunswick, or other Canadian ports, often took these

passengers free of charge.2 Thomas

Garrett, of Wilmington, Delaware, sometimes sent negroes

by steamboat to Philadelphia to be cared for by the

Vigilance Committee.3 It happened on

several occasions that fugitives at Portland and Boston

were put aboard ocean steamers bound for England.4

William and Ellen Craft were sent to England

after having narrowly escaped capture in Boston.5

On the great lakes the boat service was extensive.

The boats of General Reed touching at Racine, Wisconsin,

received fugitives without fare. Among these were the

Sultana (Captain Appleby), the

Madison, the Missouri, the Niagara and the Keystone

State. Captain Steele of the

propeller Galena was a friend of fugitives, as was also

Captain Kelsey of the Chesapeake. Mr. A. P.

Dutton was familiar with these

---------------

1 See p. 312, Chapter X.

2 Letters of Brown Thurston, Portland, Me., Jan. 13,

1893, and Oct. 21, 1895.

3 For letters from Mr. Garrett to William Still, of the

Acting Committee of Vigilance of Philadelphia, notifying

im that fugitives had been sent by boat, see Still's

Underground Railroad Records, pp. 380, 387.

4 Letter of S. T. Pickard, Portland, Me., Nov. 18,

1893.

5 Still, Underground Railroad Records, p. 368;

Wilson, Rise and Fall of the Slave Power, Vol.

II, p. 325; New England Magazine, January, 1890,

p. 580.

[Pg. 83] - TRAFFIC BY WATER

vessels and their officers, and for

twenty years or more shipped runaway slaves as well as

cargoes of grain from his dock in Racine.1

The Illinois (Captain Blake), running

between Chicago and Detroit, was a safe boat on which to

place passengers whose destination was Canada.2

John G. Weiblen navigated the lakes in 1855 and

1856, and took many refugees from Chicago to

Collingwood, Ontario.3 The Arrow,4

the United States,5 the Bay City and the

Mayflower plying between Sandusky and Detroit, were

boats the officers of which were always willing to help

negroes reach Canadian ports. The Forest Queen,

the Morning Star and the May Queen, running between

Cleveland and Detroit, the Phoebus, a little boat plying

between Toledo and Detroit, and, finally, some scows and

sail-boats, are among the old craft of the great lakes

that carried many slaves to their land of promise.6

A clue to the number of refugees thus transported to

Canada is perhaps given by the record of the boat upon

which the fugitive, William Wells Brown,

found employment. This boat ran from Cleveland to

Buffalo and to Detroit. It quickly became known at

Cleveland that Mr. Brown would take

escaped slaves under his protection without charge,

hence he rarely failed to find a little company ready to

sail when he started out from Cleveland. “In the

year 1842,” he says, “I conveyed, from the first of May

to the first of December, sixty-nine fugitives over Lake

Erie to Canada.”7

The account of the method of the Underground Railroad

could scarcely be called complete without some notice of

the rescue of fugitives under arrest. The first

rescue occurred at the intended trial of the first

fugitive slave case in Boston in 1793. Mr.

Josiah Quincy, counsel for the fugitive, “

heard

---------------

1 Letter of A. P. Dutton, of Racine, Wis.,

Apr. 7, 1896. As a shipper of grain and an

abolitionist for twenty years in Racine, Mr. Dutton was

able to turn his dock into a place of deportation for

runaway slaves.

2 A. J. Andreas, History of Chicago,

Vol. I, p. 606.

3 Letter of Mr. Weiblen, Fairview, Erie Co.,

Pa., Nov. 26, 1895.

4 The Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888,

p. 46.

5 Ibid., p. 50.

6 The names of the last six boats given, as

well as several of the others, were obtained from

freedmen in Canada, who keep them in grateful

remembrance.

7 Narrative of William W. Brown, by

himself, 1838, pp. 107, 108.

[Pg. 84]

a noise, and, turning around, saw the

constables lying sprawling on the floor, and a passage

opening through the crowd, through which the fugitive

was taking his departure without stopping to hear the

opinion of the court.”1

The prototype of deliverances thus established was, it is true more or

less deviated from in later instances, but the general

characteristics of these cases are such that they

naturally fall into one class. They are cases in

which the execution of the law was interfered with by

friends of the prisoner, who was spirited away as

quickly as possible. The deliverance in 1812 of a

supposed runaway from the hands of his captor by the New

England settlers of Worthington, Ohio, has already been

referred to in general terms.2 But some

details of the incident are necessary to bring out more

clearly the propriety of its being included in the

category of instances of violation of the constitutional

provision for the rendition of escaped slaves. It

appears that word was brought to the village of

Worthington of the capture of the fugitive at a

neighboring town, and that the villagers under the

direction of Colonel James Kilbourne

took immediate steps to release the negro, who, it was

said, was tied with ropes, and being afoot, was

compelled to keep up as best he could with his master’s

horse. On the arrival of the slave-owner and his

chattel, the latter was freed from his bonds by the use

of a butcher-knife in the hands of an active villager,

and the forms of a legal dismissal were gone through

before a court and an audience whose convictions were

ruinous to any representations the claimant was able to

make. The dispossessed master was permitted to

continue his journey southward, while the negro was

directed to get aboard a government wagon on its way

northward to Sandusky. The return of the

slave-hunter a day or two later with a process obtained

in Franklinton, authorizing the retaking of his

property, secured him a second hearing, but did not

change the result. A fugitive, Basil

Dorsey, from Liberty, Frederick County, Maryland,

was seized in Bucks County, Pennsyl-

---------------

1 Mr.

Quincy's report of the case, quoted by M. G. McDougall,

Fugitive Slaves, p. 35.

2 See p. 38.

[Pg. 85] - RESCUE OF FUGITIVES

UNDER ARREST

vania, in 1886, and carried away.

Overtaken by Mr. Robert Purvis at Doylestown, be was

brought into court, and the hearing of the case was

postponed for two weeks. When the day of trial

came the counsel for the slave succeeded in getting the

case dismissed on the ground of certain objections.

Thereupon the claimants of the slave hastened to a

magistrate for a new warrant, but just as they were

returning to rearrest the fugitive, he was hustled into

the buggy of Mr. Purvis and driven rapidly

out of the reach of the pursuers.1 In

October, 1858, the case of Louis, a fugitive from

Kentucky on trial in Cincinnati, was brought to a

conclusion in an unexpected way. The United States

commissioner was about to pronounce judgment when the

prisoner, taking advantage of a favorable opportunity,

slipped from his chair, had a good hat placed upon his

head by some friend, passed out of the court-room among

a crowd of colored visitors and made his way cautiously

to Avondale. A few minutes after the disappearance

of the fugitive his absence was discovered by the

marshal that had him in charge; and although careful

search was made for him, he escaped to Canada by means

of the Underground Railroad.2 In April,

1859, Charles Nalle, a slave from Culpeper

County, Virginia, was discovered in Troy, New York, and

taken before the United States commissioner, who

remanded him back to slavery. As the news of this

decision spread, a crowd gathered about the

commissioner’s office. In the meantime, a writ of

habeas corpus was served upon the marshal that had

arrested Nalle, commanding that officer to bring

the prisoner before a judge of the Supreme Court.

When the marshal and his deputies appeared with the

slave, the crowd made a charge upon them, and a

hand-to-hand melee resulted. Inch by inch the

progress of the officers was resisted until they were

worn out, and the slave escaped. In haste the

fugitive was ferried across the river to West Troy, only

to fall into the hands of a constable and be again taken

into custody. The mob had followed, however, and

now stormed the door behind which the prisoner rested

under guard. In the attack

---------------

1 Smedley,

Underground Railroad, pp. 356-361.

2 Levi Coffin, Reminiscences, pp. 548-554.

[Pg. 86]

the door was forced open, and over the body of a negro

assailant, struck down in the fray, the slave was torn

from his guards, and sent on his way to Canada.1

Well-known cases of rescue, such as the Shadrach case,

which occurred in Boston in January, 1851, and the Jerry

rescue, which occurred in Syracuse nine months later,

may be omitted here. They, like many others that

have been less often chronicled, show clearly the temper

of resolute men in the communities where they occurred.

It was felt by these persons that the slave,

who had already paid too high a penalty for his color,

could not expect justice at the hands of the law, that

his liberty must be preserved to him, and a base statute

be thwarted at any cost.

---------------

1 This account is condensed from a report

given in the Troy Whit, April 28, 1859, and

printed in the book entitled, Harrriet the Moses of

Her people, pp. 143-149.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS |