|

CHAPTER VII

LIFE OF THE COLORED REFUGEES IN CANADA

Pg. 190

The passengers of the

Underground Railroad had but one real refuge, one region

alone within whose bounds they could know they were safe

from reënslavement;

that region was Canada. The position of Canada on

the slavery question was peculiar, for the imperial act

abolishing slavery throughout the colonies of England

was not passed until 1833; and, legally, if not

actually, slavery existed in Canada until that year. The

importation of slaves into this northern country had

been tolerated by the French, and later, under an act

passed in 1790, had been encouraged by the English.

It is a singular fact that while this measure was in

force slaves escaped from their Canadian masters to the

United States, where they found freedom.1

Before the separation of the Upper and Lower Provinces

in 1791, slavery had spread westward into Upper Canada,

and a few hundred negroes and some Pawnee Indians were

to be found in bondage through the small scattered

settlements of the Niagara, Home and Western districts.

The Province of Upper Canada took the initiative in the

restriction of slavery. In the year 1793, in which

Congress provided for the rendition by the Northern

states of fugitives from labor, the first parliament of

Upper Canada enacted a

---------------

1 "A case of this kind," says Dr. S. G. Howe,"

was related to us byMrs. Amy Martin. She

says: "My father's name was James Ford . . . . He

. . . would be over one hundred years old, if he were

now living . . . . He was held here (in Canada) by the

Indians as a slave, and sold, I think he said to a

British officer, who was a very cruel master, and he

escaped from him, and came to Ohio, . . . to Cleveland,

I believe, first, and made his way from there to Erie

(Pa.), where he settled . . . . When we were in Erie, we

moved a little way out of the village, and our house was

. . . a station of the U. S. R. R." The

Refugees from Slavery in Canada West, by S. G.

Howe, 1864, pp.8, 9.

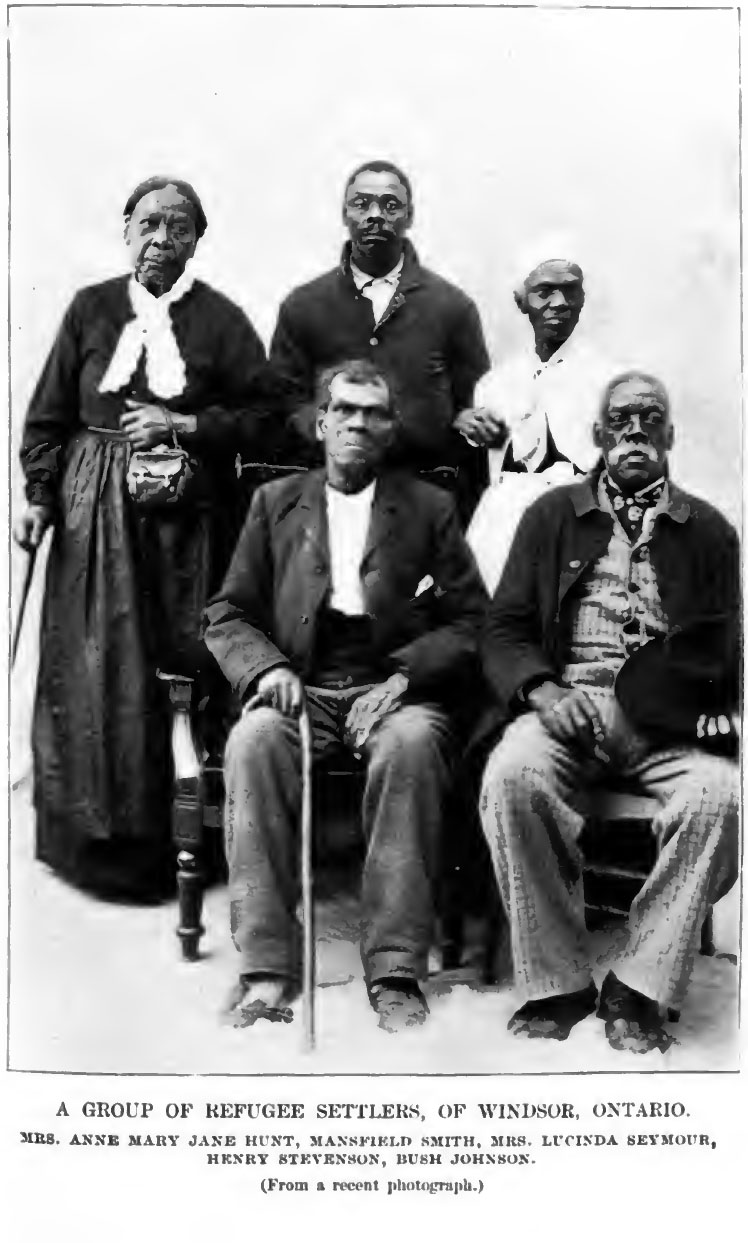

A GROUP OF REFUGEE SETTLERS, OF WINDSOR, ONTARIO

MRS. ANN MARY JANE HUNT, MANSFIELD SMITH, MRS. LUCINDA

SEYMOUR, HENRY STEVENSON, BUSH JOHNSON.

(From a recent photograph.)

[Pg. 191] -

DISAPPEARANCE OF SLAVERY FROM CANADA

law against the

importation of slaves, and incorporated in it a clause

to the effect that children of slaves then held were to

become free at the age of twenty-five years.1

Nevertheless, judicial rather than legislative action

terminated slavery in Lower Canada, for a series of

three fugitive slave cases occurred between the first

day of February, 1798, and the last day of February,

1800. The third of these suits, known as the Robin

case, was tried before the full Court of King's Bench,

and the court ordered the discharge of the fugitive from

his confinement. Perhaps the correctness of the

decisions rendered in these cases may be questioned; but

it is noteworthy that the provincial legislature would

not cross them, and it may therefore be asserted that

slavery really ceased in Lower Canada after the decision

of the Robin case, Feb.18, 1800.2

The seaboard provinces were but little infected by

slavery. Nova Scotia, to which probably more than

to any other of these, refugees from Southern bondage

fled, had be reason of natural causes, lost nearly, if

not quite all traces of slavery by the beginning of our

century. The experience of the eighteenth century

had been sufficient to reform public opinion in Canada

on the question of slavery, and to show that the climate

of the provinces was a permanent barrier to the

profitable employment of slave labor.

During the period in which Canada was thus freeing

herself from the last vestiges of the evil, slaves who

had escaped from Southern masters were beginning to

appeal for protection to anti-slavery people in the

Northern states.3 The arrests of

refugees from bondage, and the cases of kidnapping of

free negroes, which were not infrequent in the North,

strengthened the appeals of the hunted suppliants.

Under these circumstances, it was natural that there

should have arisen early in the present century the

beginnings of a movement on thenorthern border of the

United States for the purpose of helping fugitives to

Canadian soil.4

---------------

1 Act of 30th Geo. III.

2 See the article entitled "Slavery in

Canada," by J. C. Hamilton, LL.B.

3 M. G. McDougall, Fugitive Slaves,

p. 20.

4 Ibid., p. 60; R. C. Smedley,

Underground Railroad, p. 26.

[Pg. 192]

Upon the questions how and when this system arose, we

have both unofficial and official testimony. Dr.

Samuel G.

Howe learned upon careful investigation, in 1863,

that the early abolition of slavery in Canada did not

affect slavery in

the United States for several years. "Now and then

a slave was intelligent and bold enough," he states, "to

cross the

vast forest between the Ohio and the Lakes, and find a

refuge beyond them. Such cases were at first very

rare, and knowledge of them was confined to few; but

they increased early in this century; and the rumor

gradually spread among the slaves of the Southern

states, that there was, far away under the north star, a

land where the flag of the Union did not float; where

the law declared all men free and equal; where the

people respected the law, and the government, if need

be, enforced it. . . . Some, not

content with personal freedom and happiness, went

secretly back to their old homes, and brought away their

wives and children at much peril and cost. The

rumor widened; the fugitives so increased, that a secret

pathway, since called the Underground Railroad, was soon

formed, which ran by the huts of the blacks in the slave

states, and the houses of good Samaritans in the free

states. . . . Hundreds trod this path

every year, but they did not attract much public

notice."1 Before the year 1817 it is

said that a single little group of abolitionists in

southern Ohio had forwarded to Canada by this secret

path more than a thousand fugitive slaves.2

The truth of this account is confirmed by the diplomatic

negotiations of 1826 relating to 0this subject.

Mr. Clay, then Secretary of State, declared

the escape of slaves to British territory to be a

"growing evil"; and in 1828 he again described it as

still "growing," and added that it was well calculated

to disturb the peaceful relations existing between the

United States and the adjacent British provinces.

England, however, steadfastly refused to accept Mr.

Clay's proposed stipulation for extradition, on

the ground that the British government could not, "with

respect to the British possessions where slavery is not

admitted, de-

---------------

1 S. G. Howe,

The Refugees from Slavery in Canada West, pp. 11,

12.

2 William Birney, James G. Birney and His

Times, p. 435.

[Pg. 193] -

INFLUX OF FUGITIVES INTO CANADA.

part from the principle

recognized by the British courts that every man is free

who reaches British ground."1

During the decade between 1828 and 1838 many persons

throughout the Northern states, as far west as Iowa, had

cooperated in forming new lines of Underground Railroad

with termini at various points along the Canadian

frontier. A resolution submitted to Congress in

December, 1838, was aimed at these persons, by calling

for a bill providing for the punishment, in the courts

of the United States, of all persons guilty of aiding

fugitive slaves to escape, or of enticing them from

their owners.2 Though this resolution

came to nought, the need of it may have been

demonstrated to the minds of Southern men by the fact

that several companies of runaway slaves were organized,

and took part in the Patriot War of this year in defence

of Canadian territory against the attack of two or three

hundred armed men from the State of New York.3

Each succeeding year witnessed the influx into Canada

of a larger number of colored emigrants from the South.

At length, in 1850, the Fugitive Slave Law called forth

such opposition in the North that the Underground

Railroad became more efficient than ever. The

secretary of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society

wrote in 1851 that, "notwithstanding the stringent

provisions of the Fugitive Bill, and the confidence

which was felt in it as a certain cure for escape, we

are happy to know that the evasion of slaves was never

greater than at this moment. All abolitionists, at

any of the prominent points of the country, know that

applications for assistance were never more frequent."4

This statement is substantiated by the testimony of many

persons who did underground service in the North.

---------------

1 Mr.

Gallatin to Mr. Clay, Sept. 26, 1827, Niles'

Register, p. 290.

2 Congressional Globe, Twenty-fifth

Congress, Third Session, p. 34.

3 The Patriot War defeated a foolhardy

attempt to induce the Province of Upper Canada to

proclaim its independence. The refugees were by no

means willing to see a movement begun, the success of

which might "break the only arm interposed for their

security." J. W. Loguen as a Slave and as a

Freeman, p. 344.

4 Nineteenth Annual Report of the

Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, January, 1851,

p. 67.

[Pg. 194]

[Pg. 195] - CHARACTER OF CANADIAN

REFUGEES

[Pg. 196]

[Pg. 197] - MISINFORMATION ABOUT

CANADA AMONG SLAVES

[Pg. 198]

[Pg. 199] - TREATMENT OF REFUGEES IN

CANADA -

[Pg. 200]

[Pg. 201] - ATTITUDE OF CANADA

TOWARDS FUGITIVES

[Pg. 202]

[Pg. 203] - CONDITIONS IN CANADA

[Pg. 204]

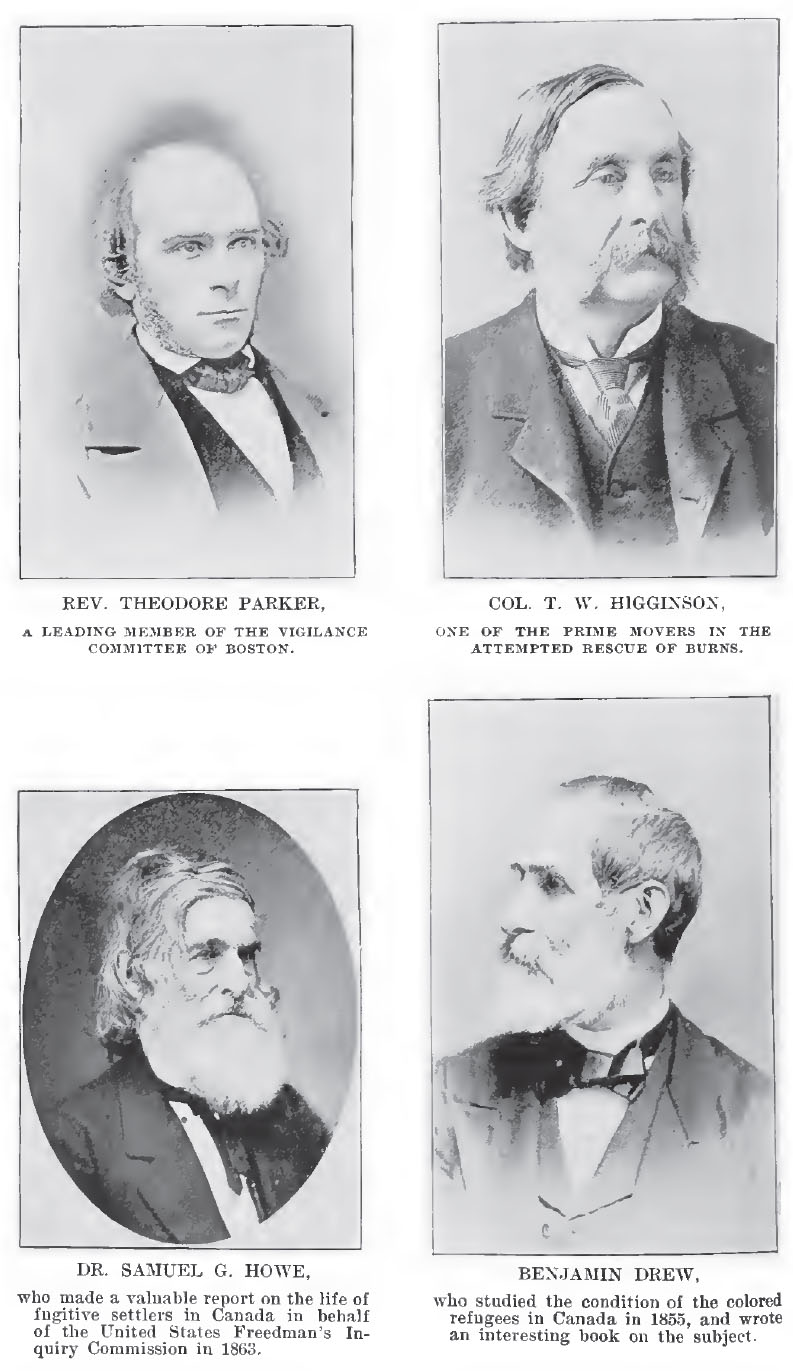

REV. THEODORE PARKER

COL. T. W. HIGGINSON

DR. SAMUEL G. HOWE

BENJAMIN DREW

[Pg. 205] - FUGITIVE AID SOCIETIES IN

CANADA

[Pg. 206] -

[Pg. 207] - DAWN SETTLEMENT -

[Pg. 208] -

[Pg. 209] - ELGINAND REFUGEES' HOME

SETTLEMENTS -

[Pg. 210] -

[Pg. 211] - DR. HOWE'S CRITICISM OF

THE COLONIES -

[Pg. 212] -

[Pg. 213] - DR. HOWE'S CRITICISM

ANSWERED -

[Pg. 214] -

[Pg. 215] - SERVICES OF THE

COLONIZATION SOCIETIES -

[Pg. 216] -

[Pg. 217] - CONCLUSIONS CONCERNING

THE COLONIES -

[Pg. 218] -

[Pg. 219] - REFUGEES IN THE EASTERN

PROVINCES -

[Pg. 220] -

[Pg. 221] - REFUGEE POPULATION OF

CANADA -

[Pg. 222] -

[Pg. 223] - OCCUPATIONS OF CANADIAN

REFUTEES -

[Pg. 224] -

[Pg. 225] - CONGREGATION OF FUGITIVES

IN TOWNS -

[Pg. 226] -

[Pg. 227] - PROGRESS OF CANACIAN

REFUGEES -

[Pg. 228] -

[Pg. 229] - SCHOOLS OF THE REFUGEES -

[Pg. 230] -

[Pg. 231] - TRUE BANDS AMONG THE

REFUGEES -

[Pg. 232] -

[Pg. 233] - POLITICAL PRIVILEGES OF

REFUGEES -

[Pg. 234] -

Howe, that the refugees "promote the industrial and

material interests of the country and are valuable

citizens."1

---------------

1 The Refugees from Slavery in Canada West, p.

102. William Still, who made a trip through

Canada Wet in 1855, expressed a view similar to that

above quoted, and added the words: "To say that there

are not those amongst the colored people in Canada, as

every place, who are very poor, . . . who will commit

crime, who indulge in habits of indolence and

intemperance, . . . would be far from the truth.

Nevertheless, may not the same be said of white people,

even where they have had the best chances in every

particular? " Underground Railroad Records, p.

xxviii.

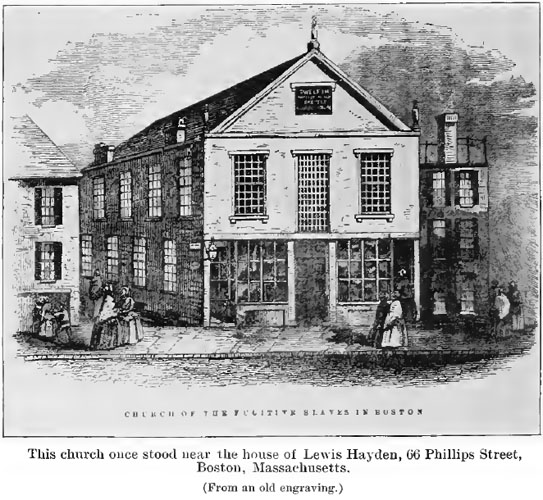

This church once stood near the house of Lewis Hayden,

66 Phillips Street, Boston, Massachusetts.

(From an old engraving)

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS |