|

CHAPTER IX

PROSECUTIONS OF UNDERGROUND

RAILROAD MEN

Pg. 254 -

THE aversion

to a law for the rendition of fugitive slaves that early

manifested itself in the North was perhaps fore-shadowed

in the hesitating manner in which the question was dealt

with by Congress. The original demand for

legislation was caused by the activity of kidnappers in

Pennsylvania; but the first bill, reported from

committee to the House in November, 1791, was dropped

for soe reason not now discoverable. At the end of

March in the following year a committee of the Senate

was appointed to consider the matter, but it

accomplished nothing. At the beginning of the next

session a second Senate committee was chosen, and from

this body a bill emanated. This bill proved to be

unsatisfactory, however, and after the committee had

been remodelled by the addition of two new members the

bill was recommitted with instructions to amend.

With some slight change the measure proposed by the

committee was adopted by the Senate, January 18; and

after an interval of nearly three weeks the House passed

it with little or no debate, by a vote of forty-eight to

seven. Thus for nearly a year and a quarter the

subject was under the consideration of Congress before

it could be embodied in a bill and sent to the executive

for his signature. On Feb. 12, 1793, President

Washington signed this bill and it became a law.1

The object of the law was, of course, to enforce the

constitutional guarantee in regard to the delivery of

fugitives from service to their masters. An

analysis of the law will show that forcible seizure of

the alleged fugitive was authorized; that the decision

of the magistrate before whom he was to be taken was

allowed to turn on the testimony of the master, or

---------------

1. M. G. McDougall, Fugitive

Slaves, pp. 17, 18.

SALMON P. CHASE,

of Ohio

known as

"attorney-general for fugitive slaves," on account of

his frequent appearance as counsel in fugitive slave

cases.

THOMAS GARRETT,

of Wilmington, Delaware,

who aided 2700

runaways, and paid $8000 in fines for his violations of

the slave laws.

[Pg. 255] - GROUNDS OF

ATTACK UPON THE SLAVE LAWS

the affidavit of some magistrate in the state from which

he came; and that trial by jury was denied.

Persons attempting to obstruct the law by harboring or

concealing a fugitive slave, resisting his arrest, or

securing his rescue, were liable to a fine of five

hundred dollars for the benefit of the claimant, and the

right of action on account of these injuries was

reserved to the claimant.1

The exclusive regard for the rights of the owner

exhibited in these provisions was fitted to stir the

popular sense of justice in the Northern states most of

which had already ranged themselves by individual action

on the side of liberty. Persons moved by the

appeals of the hunted negro to transgress the statute

would naturally try to avoid its penalties by

concealment of their acts, and this we know was what

they did. The whole movement denominated the

Underground Railroad was carried on in secret, because

only thus could the fugitives, in whose behalf it

originated, and their abettors, by whom it was

maintained, be secure from the law. When through

mischance or open resistance, as sometimes happened, an

offender against the law was discovered and brought to

trial, the case was not allowed to progress far before

the Fugitive Recovery Act itself was assailed vigorously

by the counsel for the defendant. The grounds of

attack included the absence of provision for jury trial,

the authority of the claimant or his agent to arrest

without a warrant, the antagonism between state and

federal legislation, the supposed repugnancy of the law

of 1793 to the Ordinance of 1787, the denial of the

power of Congress to legislate on the subject of

fugitive slaves, and the question as to the

responsibility for the execution of the law.

Nearly if not all of these disputed points were involved

in the great question as to the constitutionality of the

congressional act, a question that kept working up

through the successive decisions of the courts to

irritate and disturb the peace between the sections,

that the fugitive clause in the federal Constitution,

the act of 1793 itself, and the judicial affirmations

following in their train were intended to promote.

The omission of a provision from the law of Congress

secur-

---------------

1. Statutes at Large, I, 302-305.

[Pg. 256]

ing trial by jury to the alleged fugitive was at once

remarked by the friends of the bondman, and caused the

law to be denounced in the court-room as worthy only of

the severest condemnation.1 As early as 1819, in

the case of Wright vs. Deacon,

tried before the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, it was

urged that the supposed fugitive was entitled to a jury

trial, but the arguments made in support of the claim

have not been preserved.2 The question was

presented in several subsequent cases of importance

arising under the law of 1793, namely Jack vs.

Hoppess, in 1845.5 From the reports of

these cases one is not able to gather much in the way of

direct statement showing what were the grounds

---------------

1.

Professor Eugene Wambaugh, of the Law School of

Harvard University, in a letter to the author, comments

as follows on the source of the injustice wrought by the

Fugitive Slave acts: "The difficulty lay in the initial

assumption that a human being can be property.

Grant this assumption, and there follow many

absurdities, among them the impossibility of framing a

Fugitive Slave Law that shall be both logical and

humane. Human beings are entitled to a trial of

the normal sort, especially in a case involving the

liability of personal restraint. Chattels,

however, are entitled to no trial at all; and it a

chattel be lost or stolen, the owner may retake it

wherever he finds it, provided he commits no breach of

the peace. (3 Blackstone's Commentaries, 4.)

If slaves had been treated as ordinary chattels, there

could have been no trial as to the ownership of them,

unless, indeed, there were a dispute between competing

claimants. There would have been, however, the

fatal objection that thus a free man - black, mulatto,

or white - might be enslaved without

a hearing. Here, then, is a puzzle. If the

man is a slave, he is entitled to no trial at all.

If he is free, he is entitled to a trial of the most

careful sort, surrounded with all the safeguards that

have been thrown up by the law. When there is such

a dilemma, is it strange that there should be a

compromise? The Fugitive Slave Laws really were a

compromise; for in so far as they provided for an

abnormal and incomplete trial, a hearing before a United

States Commissioner, simply to determine rights as

between the supposed slave and the supposed master, they

conceded the radical impossibility of following out

logically the supposition that human beings can be

chattels, and, in so far as they denied to the supposed

slave the normal trial, they assumed in advance that he

was a slave. I need not vn-ite of the dilemma

further. A procedure intermediate between a formal

trial and a total denial of justice was probably the

only solution practicable in those days; but it was an

illogical solution, and the only logical solution was

emancipation."

2 5 Sergeant and Rawle's Reports, 63.

See Appendix B, p. 368.

3 14 Wendells Reports, 514. See

Appendix B, p. 368.

4 In the Circuit Court of the United States

for the Southern District of New York. 2 Paine's

Reports, 352.

5 2 Western Law Journal, 282.

[Pg. 257] - DENIAL OF

TRIAL BY JURY

taken for the advocacy of trial by jury in such cases,

but the indications that appear are not to be mistaken.

In all of these cases it seems to have been insisted

that the law of 1793 failed to conform to the

constitutional requirement on this point; and in State

vs. Hoppess it is distinctly stated that the law

provided for a trial of the most important right without

a jury, contrary to the amendment of the Constitution

declaring that "In suits at common law, where the value

shall exceed twenty dollars, the right of trial by jury

shall be preserved . . .";1 and that the act

also authorized the deprivation of a person of his or

her liberty contrary to another amendment, which

declares that no person shall be "deprived of life,

liberty, or property, without due process of law."2

In Jack vs. Martin, as

probably in the other cases, the obvious objection seems

to have been made that the denial of the jury

contributed to make easy the enslavement of free

citizens. The courts, however, did not sustain

these objections; thus, for example, in the last case

named, Judge Nelson, while admitting the defect

of the law, decided in conformity with it,3

and the claims upon the constitutional guarantees,

asserted in behalf of the supposed fugitive, were also

overruled, a reason given in the case of Wright

vs. Deacon being that the evident scope

and tenor of both the Constitution and the act of

Congress favored the delivery of the fugitive on a

summary proceeding without the delay of a formal trial

in a court of common law. Another reason offered

by the court in this case, and repeated by the Circuit

Court of the United States for the Southern District of

New York in the matter of Peter, alias Lewis

Martin, was that the examination under the

federal slave law was only preliminary, its purpose

being merely to determine the claimant's right to carry

the fugitive back to the state whence he had fled, where

the question of slavery would properly be open to

inquiry. The mode of arrest permitted by the law

was a cause of irritation to the minds of abolitionists

throughout the free states, and became one of the points

concerning which they joined issue in the courts.

The law empowered the claimant

---------------

1 Amendments, Article

VII.

2 Ibid., Article V.

3 12 Wendells Reports, 315-324.

[Pg. 258]

to seize the fugitive wheresoever found for the purpose

of taking him before an officer to prove property.

The circumstances that quickened the sympathy of a

community into active resistance to this feature of the

law are fully illustrated in one of the earliest cases

coming before a high court, in which the question of

seizure was brought up for determination. The case

is that of Commonwealth vs. Griffith,

which was tried in the Supreme Judicial Court of

Massachusetts, at the October term in 1823. From

the record of the matter appearing in the law-books, one

gathers that a slave, Randolph, who had fled from

his master in Virginia, found a refuge in New Bedford

about 1818, where by his thrift he acquired a

dwelling-house. After several years he was

discovered by Griffith, his owner's agent, and

was seized without a warrant or other legal process,

although the agent had taken the precaution to have a

deputy sheriff present. The agent's intention was

to take the slave before a magistrate for examination,

pursuant to the act of 1793.1 New

Bedford was a Quaker town, and the slave seems not to

have lacked friends, for the agent was at once indicted

for assault and battery and false imprisonment.

The action thus begun was prosecuted in the name of the

state, under the direction of Mr. Norton,

the attorney-general. As against the act of

Congress the prosecution urged that the Constitution did

not authorize a seizure without some legal process, and

that such a seizure would manifestly be contrary to the

article of the amendments of the Constitution that

asserted the right of the people to be secure in their

persons, houses, papers and effects, against

unreasonable searches and seizures.2

The protest that if the law was constitutional any

citizen's house might be invaded without a warrant under

pretence that a negro was concealed there called forth

the interesting remark from Chief Justice

Parker that a case arising out of a constable's

entering a citizen's house without warrant in search of

a slave had come before him in Middlesex, and that he

had held the act to be a trespass. Nevertheless,

the court sustained the law

---------------

1 2

Pickering's Reports, 12. See Appendix B, p. 368.

2 Amendments, Article IV ; 2 Pickering's

Reports, 15, 16.

[Pg. 259] - ARREST

WITHOUT LEGAL PROCESS

on the ground that slaves

were not parties to the Constitution, and that the

amendment referred to had relation only to the parties.1

The question of arrest without warrant emerged later in

several other cases; for example, Johnson vs.Tompkins

(1833),2 the matter of Peter, alias

Lewis Martin (1837),3 Prigg vs.

Pennsylvania (1842),4 and State vs.

Hoppess (1845).5 The

line of objection followed by those opposing the law in

this series will be sufficiently indicated by the

arguments presented in the Massachusetts case of 1823,

treated above. The tribunals before which the later

suits were brought did not depart from the precedent set

in the early case, and the act of 1793 was invariably

justified. In Johnson vs.

Tompkins the court pointed out that under the law

the claimant was not only free to arrest his fugitive

without a warrant, but that he was also free to do this

unaccompanied by any civil officer, although, as was

suggested, it was the part of prudence to have such an

officer to keep the peace.6 In the

famous case of Prigg vs. Pennsylvania, the

Supreme Court of the United States went back of the law

of Congress to the Constitution in seeking the source of

the master's right of recaption, and laid down the

principle that "under and in virtue of the Constitution,

the owner of a slave is clothed with entire authority,

in every state in the Union, to seize and recapture his

slave, whenever he can do it without any breach of the

peace, or any illegal violence. In this sense and

to this extent this clause of the Constitution may

properly be said to execute itself, and to require no

aid from legislation, state or national."7

For many years before Prigg's case various

states in the North had considered it to be within the

province of their

---------------

1 2

Pickering's Reports, 19.

2 In the Circuit Court of the United States

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. 1

Baldwin's Circuit Court Reports, p. 571 et seq.

See Appendix B, p. 368.

3 2 Paine's Reports, 350. See

Appendix B, p. 369.

4 16 Peters' Reports, 613.

5 2 Western Law Journal, 282.

See Appendix B, p. 371.

6 1 Baldwin's Circuit Court Reports,

571; Hurd, Law of Freedome and Bondage,

Vol. II, p. 444.

7 16 Peters'

Reports, 613.

[Pg. 260]

legislative powers to enact laws dealing with the

subject of fugitive slaves. It would be beside our

purpose to enter here upon an examination of these

statutes, but it is proper to say that the variety of

particulars in which these differed from the law

concerning the same subject enacted by Congress prepared

the way for a series of legal contests in regard to the

question, whether the power to legislate in relation to

fugitive slaves could be exercised properly by the

states as well as by the federal government. This

issue presented itself in at least three notable cases

under the law of 1793: these were Jack vs. Martin

(1835), Peter, alias Lewis Martin (1837), and

Prigg vs. Pennsylvania (1842). The

decisions reached in the first and last cases are of

especial significance, because, in the first, the

question of concurrent jurisdiction constituted the

subject of main interest for the Supreme Court of New

York, the court to which the case had been taken from an

inferior tribunal; while in the last case, the

importance attaches to the conclusive character of an

adjudication pronounced by the most exalted court of the

nation.

In Jack vs. Martin the action was

begun under the New York law of 1828 for the recovery of

a fugitive from New Orleans. Notwithstanding the

fact that this law authorized the seizure and return of

fugitives to their owners, and that in the case before

us, as occurred also in the case of Peter,

alias Lewis Martin, the negro was

adjudged to his claimant, the law of the state was

considered invalid, because the right of legislation on

the subject was held to belong exclusively to the

national government.1

In Prigg's case2 a statute of

Pennsylvania, passed in 1826, and bearing the suggestive

title, "An act to give effect to the provisions of the

Constitution of the United States relative to fugitives

from labor, for the protection of free people of color,

and to prevent kidnapping," was violated by Edward

Prigg in seizing and removing a fugitive slave-woman

and her children from York County, Pennsylvania, into

Maryland, where their mistress lived. In the

argument made before the Supreme Court in support of the

state law, the authority of the state to legislate was

urged on the ground that

---------------

1 12 Wendell's Reports, 311,

316-318.

2 See Appendix B, p. 370.

[Pg. 261] - ANTAGONISM

BETWEEN STATE AND FEDERAL LAWS

such authority was not prohibited to the states nor

expressly granted "in terms" to Congress;1

that the statute of Pennsylvania had been enacted at the

instance of Maryland, and with a view to giving effect

to the constitutional provision relative to fugitives;2

that the states could best determine how the duty of

delivery enjoined upon them should be performed so as to

be made acceptable to their citizens;3

and that the act of Congress was silent as to the rights

of negroes wrongfully seized and of the states whose

territory was entered and laws violated by persons

acting under pretext of right.4 The

Supreme Court did not sustain these objections. A

majority of the judges agreed with Justice Story in the

view that Congress alone had the power to legislate on

the subject of fugitive slaves. The reasons given

for this view were two: first, the constitutional source

of the authority, by virtue of which the force of an act

of Congress pervades the whole Union uncontrolled by

state sovereignty or state laws, and secures rights that

otherwise would rest upon interstate comity and favor;

and, secondly, the necessity of having a uniform system

of regulations for all parts of the United States, by

which the differences arising from the varieties of

policy, local convenience and local feelings existing in

the various states can be avoided. The right to

retake fugitive slaves and the correlative duty to

deliver them were to be "coextensive and uniform in

remedy and operation throughout the whole Union."

While maintaining that the right of legislation in this

matter was exclusively vested in Congress, the court

insisted that it did not thereby interfere with the

police power of the several states, and that by virtue

of this power the states had the authority to arrest and

imprison runaway slaves, and to expel them from their

borders, just as they might do with vagrants, provided

that in exercising this jurisdiction the rights of

owners to reclaim their slaves secured by the

Constitution and the legislation of Congress were not

impeded or destroyed.5

As the friends of runaway

slaves sometimes sought to oppose to the summary

procedure of the federal law the

---------------

1 16

Peters' Reports, 579.

2 Ibid., 588-590

3 Ibid., 595.

4 Ibid., 602

5 Ibid., 612-617

[Pg. 262]

processes provided by state laws in behalf of fugitives,

so in their endeavor to overthrow the act of 1793, they

occasionally appealed to the Ordinance for the

government of the Northwest Territory. The

Ordinance, it will be remembered, contained a clause

prohibiting slavery throughout the region northwest of

the Ohio River, and another authorizing the surrender of

slaves escaping into this territory.1

The abolitionists took advantage of these provisions

under certain circumstances, in the hope of securing the

release of those that had fallen into the eager grasp of

the congressional act, and at the same time of proving

the incompatibility of this measure with the Ordinance.

The attempt to do these things was made in three

well-known cases, which came before the courts about

1845. The first of these was State vs. Hoppess,

tried before the Supreme Court of Ohio on the circuit,

to secure the liberation of a slave that had fled from

his keeper, but was afterwards recaptured;2

the second was Vaughan vs. Williams,

adjudicated in the Circuit Court of the United States

for the District of Indiana, a case originating in an

action against the defendant for rescuing certain

fugitives;3 and the third was Jones

vs. Van Zandt, which was carried to the

Supreme Court of the United States and there decided.

This last case grew out of the aid given nine runaways

by Mr. Van Zandt, through which one of them

succeeded in escaping.4 The arguments,

based upon the Ordinance, that were advanced in these

cases are adequately set forth in the report of the

first case, a report prepared by Salmon P. Chase,

subsequently Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the

United States. These arguments, two in number, were as

follows: first, the Ordinance expressly prohibited

slavery, and thereby effected the immediate emancipation

of all slaves in the Territory; and, secondly, the

clause in the Ordinance providing for the surrender of

fugitives applied only to persons held to service in the

original states.5

---------------

1 See Chap.

II, pp. 28, 32.

2 2 Western Law Journal, 279-293.

3 Western Law Journal, 65-71; also, 3

McLean^s Reports, 530-538.

4 5 Howard's Reports, 215 et seq.

5 2 Western Law Journal, 281, 283 ; 3

McLean, 530

[Pg. 263] - LAW OF

1793 VERSUS ORDINANCE OF 1787

The opinions given by the courts in the cases under

consideration failed to support the idea of the

irreconcilability existing between the law of 1793 and

the Ordinance. The Supreme Court of Ohio declared

that under the federal Constitution the right of

recaption of fugitive slaves was secured to the new

states to the same extent that it belonged to the

original states.1 The Circuit Court of

the United States took virtually the same stand by

pointing out that a state carved from the Northwest

Territory assumed the same constitutional obligations by

entering the Union that the original thirteen states had

earlier assumed, and that where a conflict occurred the

Constitution was paramount to the Ordinance.2

Finally, the Supreme Court at Washington declared that

the clause in the Ordinance prohibiting slavery applied

only to people living within the borders of the

Northwest Territory, and that it did not impair the

rights of those living in states outside of this domain.

Wheresoever the Ordinance existed the states preserved

their own laws, as well as the Ordinance, by forbidding

slavery; the provision of the Constitution and the act

of Congress looking toward the delivery of fugitive

slaves did not interfere with the laws of the free

states as to their own subjects. The court

therefore held that there was no repugnance between the

act and the Ordinance.3

Among the various objections raised in the court-room

against the law of 1793, the denial of the power of

Congress to legislate on the subject of fugitive slaves

was one that should not be overlooked. It

commanded the attention of the bench in at least two

important cases, both of which have been mentioned in

other connections, namely, Peter, alias Lewis

Martin (1837), and State vs. Hoppess

(1845). In both of these cases the denial of

legislative authority was based upon the doctrine that

there had been no delegation of the necessary power to

Congress by the Constitution. The fugitive slave

clause in the Constitution, it was said in the report of

the second case, prepared by Mr. Chase,

---------------

1 2

Western Law Journal, 288.

2 3 McLean's Reports, 532 ; 3

Western Law Journal, 65.

3 5 Howard's Reports, 230, 231.

[Pg. 264]

granted no power at all to Congress, but was "a mere

clause of compact imposing a duty on the states to be

fulfilled, if at all, by state legislation."1

However prevalent this view may have been in the

Northern states, - and the number of state laws dealing

with the subject of fugitive slaves indicates that it

predominated, - neither the Circuit Court of the United

States for the Southern District of New York in the

earlier case, nor the Supreme Court of Ohio in the

later, were willing to subscribe to the doctrine.

On the contrary, both asserted the power of Congress to

pass laws for the restoration of runaway slaves, on the

ground that the creation of a duty or a right by the

Constitution is the warrant under which Congress

necessarily acts in making the laws needful to enforce

the duty or secure the right.2

The outcome of the judicial examination in the high

courts of the various points thus far considered was

wholly favorable to the constitutionality of the law of

1793. The one case within the category of great

cases in which that law was decided to be

unconstitutional in any particular was that of Prigg vs.

Pennsylvania. By the law of 1793 state and local

authorities were empowered to take cognizance of

fugitive slave cases together with judges holding their

appointments from the federal government.3

In the hearing given the case before the Supreme Court

at Washington, in 1842, Mr. Johnson, the

attorney-general of Pennsylvania, cited former decisions

of the Supreme Court to show that in so far as the

congressional law vested jurisdiction in state officers

it was unconstitutional and void.4 The

court's answer was momentous and far-reaching.

While the law was declared to be constitutional in its

essential features, it was asserted that it did not

point out any state functionaries, or any state actions,

to carry its provisions into effect. The states

could not, therefore, so the court decided, be compelled

to enforce them; and any insistence that the states were

bound to provide means for the

---------------

1 2

Paine's Reports, 354; 2 Western Law Journal,

282.

2 Paine^s Reports, 354, 355; also, 2

Western Law Journal, 289.

3 See Section 3 of the act, Statutes at

Large, I, 302-305.

4 16 Peters' Reports, 598.

[Pg. 265] - EFFECT OF

DECISION IN PRIGG CASE

performance of the duties

of the national government, nowhere delegated or

entrusted to them by the Constitution, would bear the

appearance of an unconstitutional exercise of the

interpretative power.1 As the decision

in the Prigg case carried the weight of great

authority, and became a precedent for all future

judgments,2 the relief it afforded state

officers from distasteful functions was soon accepted by

many states, and they enacted laws forbidding their

magistrates to issue warrants for the arrest or removal

of fugitive slaves.3 In consequence of this

manifest disinclination on the part of the Northern

states to restore to Southern masters their escaped

slaves, the federal government was induced to make more

effective provision for the execution of the

Constitution in this particular. Such provision

was embodied in the second Fugitive Slave Law, passed as

a part of the Compromise of 1850.

That the new law was not intended to extinguish the old

is apparent from the title assigned it, which read: "An

Act to amend, and supplementary to, the Act entitled 'An

Act respecting Fugitives from Justice, and Persons

escaping from the service of their Masters, .

. ."4 Its evident purpose was to

increase the facilities and improve the means for the

recovery of fugitives from, labor. To this end it

created commissioners, who were to have authority, like

the judges of the circuit and district courts of the

United States, to issue warrants for the apprehension of

runaway slaves, and to grant certificates for the

removal of such persons back to the state or territory

whence they had escaped. All cases were to be

heard in a summary manner; the testimony of the alleged

fugitive could not be received in evidence; and the fee

of the commissioner or judge was to be ten dollars when

the decision was in favor of the claimant, but only five

dollars when it was unfavorable. The

penalties created by the new law were more rigorous than

those

---------------

1 16 Peters' Reports,

608, 622. See also Marion G. McDougall's

Fugitive Slaves, pp. 108, 109.

2 M. G. McDougall's Fugitive Slaves, p.

28.

3 See Chap. IX, pp. 245, 246, and Chap. X, p. 337.

4 Statutes at Large, IX, 462.

[Pg. 266]

imposed by the old. A fine not to exceed a

thousand dollars and imprisonment not to exceed six

months constituted the punishment not to exceed six

months constituted the punishment for harboring a

runaway or aiding in his rescue, and the party injured

could bring suit for civil damages against the offender

in the sum of one thousand dollars for each fugitive

lost through his interference. If the claimant

apprehended a rescue, the officer in his custody for the

purpose of removing him to the state whence he had fled.

The refusal of the officer to obey and execute the

warrants and precepts issued under the provisions of the

law laid him liable to a fine of a thousand dollars for

the benefit of the claimant; and the escape of a

fugitive from his custody, whether with his assent or

without it made him liable to a prosecution for the full

value of the labor of the negro thus lost. Ample

security from such disaster was intended to be

authorizing them to summon to their aid the bystanders,

or posse comitatus, when necessary, and all good

citizens were commanded to respond promptly with their

assistance. In removing a fugitive back to the

state from which he had escaped, when an attempt at

rescue was feared, the marshal in charge was commanded

to employ as many persons as he deemed necessary to

resist the interference. The omission of the new

law to mention any officers appointed by the states is

doubtless traceable, as is the clause establishing

commissionerships, to the ruling in the decision of

Prigg's case that state officers could not be forced

to execute federal legislation.

It will be remembered that

the decision in the Prigg case also contained a

ruling that acknowledged the right of the claimant to

seize and remove the alleged fugitive, wheresoever

found, without judicial process. It has been

suggested recently that this part of the decision,

denominated the most obnoxious part, was avoided in the

law of 1850.1 But the language of the

new law no more denied this right than

---------------

1 Henry W.

Rogers, Editor, Constitutional History of the

United States as seen in the Development of American

Law, Lecture III, by George W. Biddle, p.

152.

[Pg. 267] -

OBJECTIONABLE FEATURES OF LAW OF 1850

the language of the old bestowed it. In both cases

equally the claimant seems to have enjoyed the right of

private seizure and arrest -without process, but for the

purpose of taking the supposed fugitive before the

proper official.1 So far as the language of the

statute was concerned the Prigg decision was

quite as possible under the later as under the earlier

law. It was the language of the Constitution upon

which this part of the famous decision was made to rest,

and that, it needs scarcely be said, continued unchanged

during the period with which we are concerned.

It is not to be supposed, of course, that the law of

1850 was found to be intrinsically less objectionable to

abolitionists than the measure it was intended to

supplement. On the contrary, it soon proved to be

decidedly more objectionable. The features of the

first Slave Act that were obnoxious to the Northern

people, and had been subjected to examination in the

courts, were retained in the second act, where they were

associated with a number of new features of such a

character that they soon brought the new law into the

greatest contempt. While, therefore, the records

of the trials of the chief cases arising under the later

law are found to contain arguments borrowed from the

contentions made in the cases

---------------

1 Section 3 of the law of 1793 provided that

"the person to whom such labour or service may be due,

his agent or attorney, is hereby empowered to seize and

arrest such fugitive from labour, and to take him or her

before any judge of the circuit or district courts of

the United States, . . . within the state, or before any

magistrate of a county (etc. ) . . . wherein such

seizure . . . shall be made, and upon proof to the

satisfaction of such judge or magistrate . . . it shall

be the duty of such judge or magistrate to give a

certificate thereof . . . which shall be a sufficient

warrant for removing the said fugitive . . . to the

state or territory from which he or she fled."

Section 6 of the act of 1850 provides that "the person

or persons to whom such service or labour may be due, or

his, her, or their agent or attorney . . may pursue and

reclaim such fugitive person, either by procuring a

warrant . . . or by seizing and arresting such fugitive,

where the same can be done without process, and by

taking, or causing such person to be taken, forthwith

before such court, judge or commissioner, whose duty it

shall be to hear and determine the case ... in a summary

manner; and upon satisfactory proof . . . to make out

and deliver to such claimant, his or her agent or

attorney, a certificate . . . with authority . . to use

such reasonable force . . . as may be necessary . . . to

take and remove such fugitive person back to the State

or Territory whence he or she may have escaped as

aforesaid."

[Pg. 268]

already discussed, it is interesting to note that they

afford proof that new arguments were also brought to

bear against the act of 1850. As with the first

Fugitive Slave Law, so also with its successor, fault

was found on account of the absence of any provision for

jury trial;1 the authority of a claimant or

his agent to arrest without legal process;2

the opposition alleged to exist between the law and the

Ordinance of 1787;3 and the power said to be

improperly exercised by Congress in legislating upon the

subject of fugitive slaves.4 It is

unnecessary to introduce here a study of these points as

they presented themselves in the various cases arising,

for a discussion of them would lead to no principles of

importance other than those discovered in the cases

already examined.5

In some of the cases that were tried under the act of

1850, however, new questions appeared; and in some,

where the questions were perhaps without novelty, the

circumstances were such that the cases cannot well be

passed over in silence.

If, as was freely declared by the abolitionists, it was

possible for free negroes to be abducted from the

Northern states under the form of procedure laid down by

the act of 1793, there can be little reason to doubt

that the same thing was equally possible under the

procedure established by the act

---------------

1 Sims' case, tried before the

Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts, March term,

1851. See 7 Cushing's Reports, 310.

Miller vs. McQuerry, tried before

the Circuit Court of the United States, in Ohio, 1853.

See 5 McLean's Reports, 481-484.

Ex parte Simeon Bushnell, etc.,

tried before the Supreme Court of Ohio, May, 1859.

See 9 Ohio State Reports, 170.

2 Norris vs. Newton et al.,

tried before the Circuit Court of the United States, in

Indiana, May term, 1850. See 5 McLean's Reports,

98.

Ex parte Simeon Bushnell, etc. See

9 Ohio State Reports, 174.

United States vs. Buck, tried before the

District Court of the United States for the Eastern

District of Pennsylvania, 1860. See 8 American

Law Register, 543.

3 Booth's case, tried before the Supreme

Court of Wisconsin, June term, 1854. See 3

Wisconsin Reports, 3.

Ex parte Simeon Bushnell, and ex parte

Charles Langston, tried before the Supreme

Court of Ohio, May, 1859. See 9 Ohio State

Reports, 111, 114-117, 124, 186.

4 Sims' case. See 7 Cushing's

Reports, 290. Booth's case. See 3 Wisconsin

Reports.

5 For the text of the Slave Laws, see

Appendix A, pp. 359-366.

[Pg. 269] - POWER OF

COMMISSIONERS QUESTIONED

of 1850. Certain it is that the anti-slavery

people were not dubious on this point, but they had

scarcely had time to formulate their criticisms of the

new law when the first case under it of which there is

any record demonstrated the ease with which this

legislation could be taken advantage of in the

commission of a foul injustice. The case occurred

September 26, only eight days after the passage of the

act. A free negro, James Hamlet,

then living in New York, was arrested as the slave of

Mary Brown, of Baltimore. The hearing

took place before a United States commissioner and the

negro's removal followed at once. The community in

which Hamlet was living was greatly incensed when the

facts concerning his disappearance became known, and the

sum of money necessary for his redemption was quickly

contributed. Before a fortnight had elapsed he was

brought back from slavery.1

The summary manner in which this case was

disposed of had prevented a defence being made in behalf

of the supposed fugitive. In the next case,

however, that of Thomas Sims, which was

tried before the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts

in 1851, the negro was represented by competent counsel,

who brought forward objections against the second

Fugitive Slave Law. Almost the first of these was

directed against the power of the special officers, the

commissioners, created by the new law. It was

insisted that the authority with which these officers

were invested was distinctly judicial in character,

despite the constitutional provision limiting the

exercise of the judicial power of the United States to

organized courts of justice, composed of judges, holding

their offices during good behavior, and receiving fixed

salaries for their services.2 The same

argument seems to have been adduced in Scott's

case, tried before the District Court of the United

States in Massachusetts in 1851; in the case of

Miller vs. McQuerry, tried before the

---------------

1 Marion G. McDougall, Fugitive

Slaves, pp. 43 and 44, with the references there

given; Wilson, Rise and Fall of the Slave Power,

Vol. II, pp. 304, 305. See Appendix B, p. 372.

2 7 Cushing's Reports, 287. The

constitutional requirement will he found in Article III,

Section 1, of the Constitution of the United States.

[Pg. 270]

Circuit Court of the United States in Ohio in 1853;1

in Booth's case, argued in the Supreme Court of

Wisconsin in 1854;2 in the case known as

ex parte Robinson, adjudicated by the Circuit

Court of the United States for the Southern District of

Ohio at its April term, 1855;3 and in

the case ex parte Simeon Bushnell,

argued and determined in the Supreme Court of Ohio in

1859.4 The court met this argument by a

direct answer in four of the cases mentioned, namely,

those of Sims, Scott, Booth and

ex parte Robinson. In the first,

Sims' case. Chief Justice

Shaw pointed out that under the Slave Law of 1793

the jurisdiction over fugitive slave cases had been

conferred on justices of the peace and magistrates of

cities and towns corporate, as well as on judges of the

United States circuit and district courts, and that

evidently, therefore, the power bestowed had not been

deemed judicial in the sense in which it was urged that

the functions of the commissioners were judicial.

At the same time the judge admitted that the "argument

from the limitation of judicial power would be entitled

to very grave consideration" if it were without the

support of early construction, judicial precedent and

the acquiescence of the general and state governments.

In the trial of James Scott, on the charge

of aiding in the rescue of Shadrach (May or June,

1851), Judge Sprague, of the United States

District Court, held that the legal force of the

certificate issued by a commissioner lay merely in the

authority it conveyed to remove the person designated

from one state to another, and that the disposition made

of the person removed depended solely upon the laws of

the state to which he was taken. The facts set

down in the certificate were not, therefore, to be

considered as matters judicially established, but as

facts only in the opinion of the commissioner. In

Booth's case, the opinion of the Supreme Court of

Wisconsin contained a reference to the legality of the

power of the commissioners and sustained the objection

to their authority on the ground of unconstitutionality.5

In ex parte Robinson, Judge

McLean admitted

---------------

1 5 McLean's Reports, 481.

9 Ohio State Reports, 176

2 3 Wisconsin Reports, 39.

3 Wisconsin Reports, 64.

3 6 McLean's Reports, 359

[Pg. 271] -

REMUNERATION OF COMMISSIONERS

that the inquiry made by

the commissioner was "somewhat in the nature of judicial

power," but that the same remark applied to all the

officers of the accounting departments of the

government, as, for example, the examiners in the Patent

Office. He also remarked that the Supreme Court

had always treated the acts of the commissioners, in the

cases that had come before it, as possessed of authority

under the law.1

The uncertainly as to the precise character of the

commissioners' power displayed in the different views of

the courts before which the question was brought marks

the observations of the commissioners themselves in

regard to their authority. Examples will be found

in Sims' and Burns' cases. In the former, Mr.

George T. Curtis declared that claims for fugitive

slaves came within the judicial power of the federal

government, and that, consequently, the mode and means

of the application of this power to the cases arising

were properly to be determined by Congress. In the

latter, Mr. Edward G. Loring asserted that his

action was not judicial at all, but only ministerial.

An additional ground of objection to the commissioners

was found in the provision made in the law of 1850 for

their remuneration. When one of these officers

issuers certificate authorizing the removal of a runaway

to the state whence he had escaped, he was legally

entitled to a fee of ten dollars; when, however, he

withheld the warrant he could receive but five dollars.

Abolitionists took much offence at this arrangement, and

sometimes scornfully denominated the special appointees

under the law the "ten-dollar commissioners," and

insisted that the difference between the fees was in the

nature of a bribe held out to the officers to induce

them to decide in favor of the claimant.

Considering the prevalence of this feeling outside of

the courts, it is not surprising that objections to the

section of the act regulating the fees of commissioners

should have been taken within the court-room.2

Such objection was raised in McQuerrys case, and

was answered by Judge McLean.

---------------

1 6

McLean's Reports, 359, 360.

2. Hurd, Law of Freedom and Bondage,

Vol. II, p. 747.

[Pg. 272]

This answer is probably the only one judicially

declared, and is worth quoting: "In regard to the five

dollars, in addition, paid to the commissioner, where

the fugitive is remanded to the claimant," the judge

explained, "in all fairness it cannot be considered as a

bribe, or as so intended by Congress; but as a

compensation to the commissioner for making a statement

of the case, which includes the facts proved, and to

which the certificate is annexed. In cases where

the witnesses are numerous and the investigation takes

up several days, five dollars would scarcely be a

compensation for the statement required. Where the

fugitive is discharged, no statement is necessary."1

The fees paid to commissioners were, as indicated in

the remarks just quoted, by way of remuneration for

services rendered in inquiries relative to the rights of

ownership of negroes alleged to have escaped from the

South. These inquiries, together with similar

inquiries that arose under the act of 1793, constitute a

group by themselves. Another group is made up of

the cases growing out of the prosecution under the two

acts of persons charged with harboring fugitive slaves,

or aiding in their rescue. The secrecy observed by

abolitionists in giving assistance to escaping bondmen

shows that the evils threatening, if a discovery

occurred, were constantly kept in mind. After the

passage of the second act, public denunciation of the

measure was indulged in freely, and open resistance to

its provisions, whether these should be considered

constitutional or not, was recommended in some quarters.

Such remonstrances seem to have early disturbed the

judicial repose of the courts, for, six months after the

new Fugitive repose of the courts, for, six months after

the new Fugitive Slave Bill had become a law, Justice

Nelson found occasion in the course of a charge

to the grand jury of the Circuit Court of the United

States for the Southern District of New York to deliver

a speech on sectional issues in which he gave an

exposition of the new law, "so that those, if any there

be, who have made up their minds to disobey it, may be

fully apprised of the consequences."2

The severer penalties of the law of 1850 had

---------------

1 5 McLean's Reports, 481.

2 1 Blachford's Circuit Court Reports,

636.

[Pg. 273] - PENALTIES

FOR AIDING FUGITIVES

no deterrent effect upon

those who were determined to resist its enforcement.

The fervor displayed in harboring runaways increased

rather than diminished throughout the free states, and

the spirit of resistance thus fostered broke out in

daring and sometimes successful attempts at rescue.

Through the activity of slave-owners in seeking the

recovery of their lost property, and the support

afforded them by the government in the strict

enforcement of the new law, a number of offenders were

brought to trial and subjected to punishments inflicted

under its provisions.

Among the prosecutions arising under the two

congressional acts the following cases are offered as

typical. The number has been limited by choosing

in general from among such as came before supreme courts

of the states, or before circuit and district courts of

the United States.

One of the earliest cases of which we have record was

brought before the Circuit Court of the United States

for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania on writ of

error, in 1822. The action was for the penalty

under the law of 1793 for obstructing the plaintiff, a

citizen of Maryland, in seizing his escaped slave in

Philadelphia for the purpose of taking him before a

magistrate there to prove property. The trial in

the United States District Court had terminated in a

verdict of $500 for the slave-owner. Judge

Washington, of the Circuit Court, decided, however,

that there was an error in the judgment of the lower

court, that the judgment must be reversed with costs,

and the cause remitted to the District Court in order

that a new trial might be had. This case is known in the

law books as the case of Hill vs. Low.1

Occasionally an attempt at rescue ended in the arrest

and imprisonment of the slave-catchers, as well as the

release of the captured negro. When a party of

rescuers went to such a length as here indicated it laid

itself liable to an action for damages on the ground of

false imprisonment, as well as to prosecution for the

penalty under the Fugitive Slave Law. This is

illustrated in the case of Johnson vs.

---------------

1 4 Washington's Circuit Court Reports,

327-331.

[Pg. 274]

Tomkins, a case belonging to the year 1833.1

It was the outgrowth of the attempt of a master to

reclaim his slave from the premises of a Quaker, John

Kenderdine, of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

Before the slave-owner could return to New Jersey, the

state of his domicile, he and his party were overtaken,

and after violent handling in which the master was

injured, they were taken into custody, and were

forthwith prosecuted. The trial ended in the

acquittal of the company from New Jersey, whose seizure

of the negro was found to be justifiable. Then

followed the prosecution of some of the Pennsylvania

party for trespass and false imprisonment, before the

Circuit Court of the United States. The fact that

the defendants were all Quakers was noted by the judge,

who found it "hard to imagine" the motives by which

these persons, "members of a society distinguished for

their obedience and submission to the laws" were

actuated. The question of damages was left

exclusively to the jury. The verdict rendered was

for $4,000, and the court gave judgment on the verdict.2

The law of 1793 provided a double penalty for those

guilty of transgressing its provisions: first, the

forfeiture of a sum of $500 to be recovered for the

benefit of the claimant by action of debt; secondly, the

payment of such damages as might be awarded by the court

in an action brought by the slave-owner on account of

the injuries sustained through the loss, or even the

temporary absence, of his property. In the famous

case of Jones vs. Van Zandt,

which was pending before the United States courts, in

Ohio and at Washington, for five years, from 1842 to

1847, the defendant was compelled to pay both penalties.

In April, 1842, Mr. Van Zandt, an anti-slavery

Kentuckian, who had settled at Springdale, a few miles

north of Cincinnati, Ohio, was caught in the act of

conveying a company of nine fugitives in his

market-wagon at daybreak one morning, and,

notwithstanding the efforts of the slave-catchers, one

of the negroes escaped. The trial was held before

the United States Circuit Court at its July term, 1843.

The jury gave

---------------

1 4 Baldwin's Circuit Court Reports,

571-605.

2 Washington's Circuit Court Reports,

327-331

[Pg. 275] - PENALTIES

FOR AIDING FUGITIVES

a verdict for the

claimant of $1,200 in damages on two counts.1 Besides

the suit for damages, an action was brought against

Van Zandt for the penalty of $500. In this

action, as in the other, the verdict was for Jones,

the plaintiff. The matter did not end here,

however, and was carried on a certificate of division in

opinion between the judges to the Supreme Court of the

United States. The decision of this court was also

adverse to Van Zandt, and final judgment was

entered against him for both amounts. This

settlement was reached at the January term in 1847.2

The successful rescue of a large company of slaves was

likely to make the adventure a very expensive one for

the responsible persons that took part in it. Such

was the experience of the defendants in the case of

Giltner & Gorham and others, determined in 1847.

Six slaves, the chattels of Mr. Giltner, a

citizen of Carroll County, Kentucky, were discovered and

arrested in Marshall, Michigan, by the agents of the

claimant, but through the intervention of the defendants

were set at liberty. Action was brought to recover

the value of the negroes, who were estimated to be worth

$2,752. In the first trial the journey failed to

agree. At the succeeding term of court, however, a

verdict for the value of the slaves was found for the

plaintiff.3

The value of four negroes was involved in the case of

Norris vs. Newton and others.

These negroes were found in September, 1849, after two

years' absence from Kentucky, living in Cass County,

Michigan. Here they had taken refuge among

abolitionists and people of their own color. They

were at once seized by their pursuers and conveyed

across the line into Indiana, but had not been taken far

when their progress was stopped by an excited crowd with

a sheriff at its head. The officer had a writ of

habeas corpus, and the temper of the crowd would admit

of no delay in securing a hearing for the fugitives.

The court-house at South Bend, whither the captive were

now taken, was at

---------------

1 2

McLean's Reports, 612.

2. 5

Howard's Reports, 215-232; see also Schuckers, Life

and Public Services of S. P. Chase, 53-66; Warden,

Private Life and Public Services of S. P. Chase,

296-298.

3. 4 McLean's Reports, 402-426.

[Pg. 276]

once crowded with spectators, and the streets around it

filled with the overflow. The negroes were

released by the decision of the judge, but were

rearrested and placed in jail for safe-keeping. On the

following day warrants were sworn out against several

members of the Kentucky party, charging them with riot

and other breaches of the peace, and civil process was

begun against Mr. Norris, the owner of the

slaves, claiming large damages in their behalf.

Meanwhile companies of colored people, some of whom had

firearms and others clubs, came tramping into the

village from Cass County and the intermediate country.

Fortunately a demonstration by these incensed bands was

somehow avoided. Two days later the fugitives were

released from custody on a second writ of habeas corpus,

and, attended by a great bodyguard of colored persons,

were triumphantly carried away in a wagon. The

slave-owner, the charges against whom were dropped, had

declined to attend the last hearing accorded his slaves,

declaring that his rights had been violated, and that he

would claim compensation under the law. Suit was

accordingly brought in the Circuit Court of the United

States in 1850, and the sum of $2,850 was awarded as

damages to the plaintiff.1

Another case in which large damages were at stake was

that of Oliver vs. Weakley and

others tried in the United States Circuit Court for the

Western District of Pennsylvania, in October term, 1853.

It was alleged and proved that Mr. Weakley, one

of the defendants, had give shelter in his barn to

several slaves of the plaintiff, who was a citizen of

Maryland. The jury failed to agree on the first

trial. A second trial was therefore held, and this

time a verdict was reached; one of the defendants was

found guilty, and damages to the amount of $2,800 were

assessed upon him; the other defendants were declared

"not guilty."2

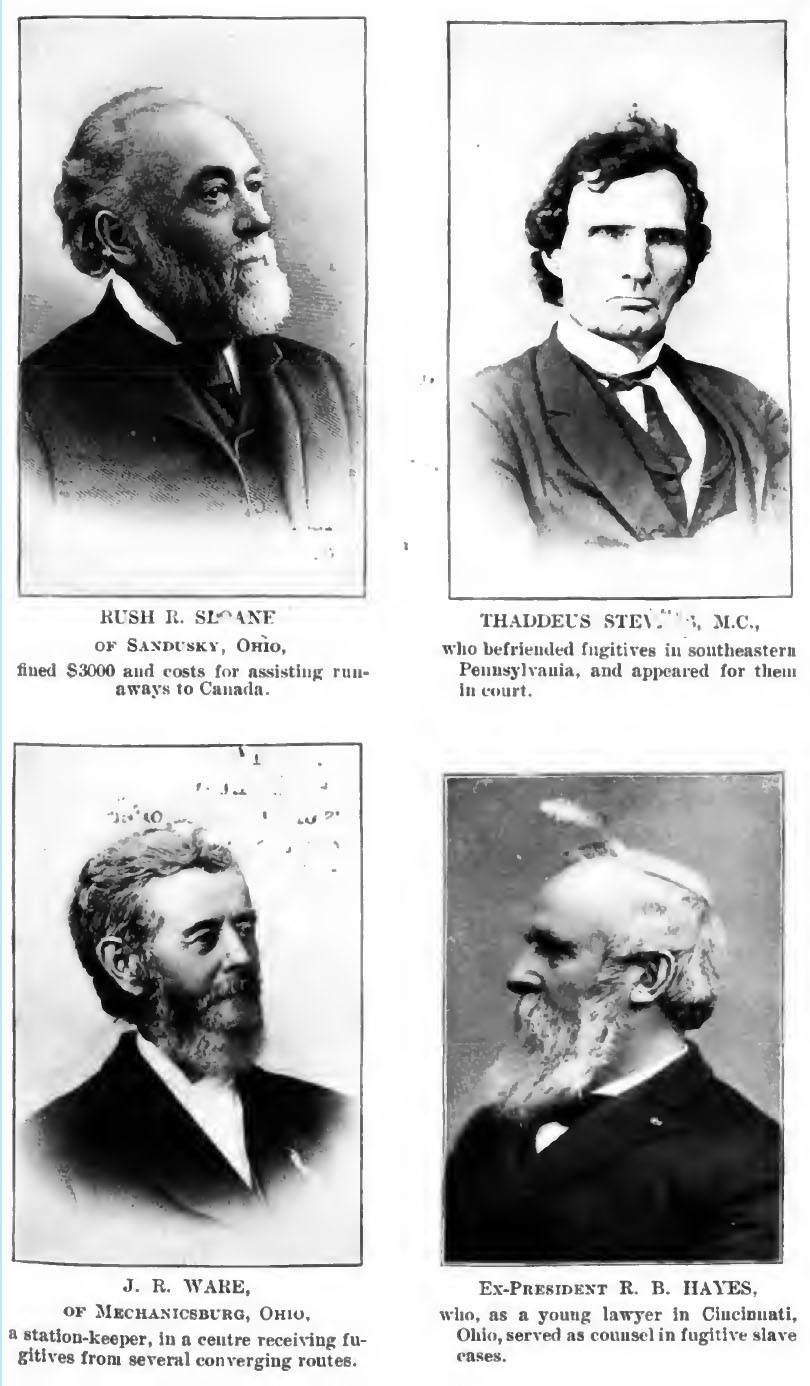

The dismissal without proper authority of seven

fugitives from the custody of their captors at Sandusky,

Ohio, by Mr. Rush R. Sloane, a lawyer of that

city, led to the institution of two suits against him by

Mr. L. F. Weimer, the claimant of three of the

slaves. The suits were tried before

---------------

1 5 McLean's Reports, 92-106.

2 2 Wallace Jr.'s Reports,

324-326

[Pg. 277] - PENALTIES

FOR AIDING FUGITIVES

the District Court of the

United States of Columbus, Ohio, in 1854, and a verdict

for $3,000 and costs was returned in favor of the

slaveholder. The costs amounted to $330.30, and

the defendant had also to pay $1,00 in attorney's fees.

Some friends of Mr. Sloane in Sandusky formed a

committee and collected $393, an amount sufficient to

pay the court and marshal's costs, but the judgment and

the other expenses were borne by the defendant

individually.1

The burden of the penalty, of which, as we have just

seen, a small fraction was assumed by sympathizers with

the offender in the case of Mr. Sloane, was

altogether removed by friendly contributors in the case

of another citizen of Sandusky. Two negroes from

Kentucky, who were being cared for at the house of

Mr. F. D. Parish, were protected from arrest by

their benefactor in February, 1845, 1845. As

Parish was a fearless agent of the Underground Road, the

fugitives were not seen afterwards in northern Ohio.

The result was that Parish was required to undergo three

trials, and in the last, in 1849, the Circuit Court of

the United States for the District of Ohio fined him

$500, the estimated value of the slaves at the time.

This sum, together with the costs and expenses,

amounting to as much more, was paid by friends of Mr.

Parish, who made up the necessary amount by

subscriptions of one dollar each.2

---------------

1 6 McLean's Reports, 259-273.

Mr. Sloane's account of the case will be found in

The Firelands Pioneer for July, 1888, pp. 46-49.

A copy of the certificate of the clerk of court there

given is here reproduced: -

"Louis F. Weimer vs. Rush R. Sloane. United

States District of Ohio, in debt.

Judgment for Plaintiff for $3000 and costs.

Received

July 8th, 1856, of Rush R. Sloane, the above

Defendant, a receipt of Louis F. Weimer the

above Plaintiff, bearing date Dec. 14th, 1854, for

$3000, acknowledging full satisfaction of the above

judgment, except the costs; also a receipt of L.

F. Weimer, Sr., per Joseph Doniphan

attorney, for $85, the amount of Plaintiff's witness

fees in said case; also $20 in money, the attorney's

docket fees attached, which, with the clerk and

marshal's fees heretofore paid, is in full of the

costs in said case.

| |

(Signed) |

WILLIAM MINER, Clerk." |

2 For

the first trial (1845), see 3 McLean's

Reports, 631; s. c. 5 Western Law Journal,

25; 7 Federal Cases, 1100; for the second

trial (1847), see

[Pg. 278]

It will have been noticed that the Van Zandt

and Parish cases were in litigation for about five years

each. A famous Illinois case, that of Dr.

Richard Eells, occupied the attention of

the courts and of the public more or less during an

entire decade. The incidents that gave rise to

this case occurred in Adams County, Illinois, in 1842.

In that year Mr. Eells was indicted for

secreting a slave owing service to Chauncey

Durkee, of Missouri, and was convicted and sentenced

to pay a fine of $400 and the costs of the prosecution.

The case was taken on writ of error first to the Supreme

Court of the state, and after the death of Mr.

Eells to the Supreme Court of the United States.

In both instances the judgment of the original tribunal

was confirmed. The decision of the federal

court was reached at its December term for 1852.1

It was sometimes made clear in the courts that the

defendants in cases arising under the Fugitive Slave

laws were persons in the habit of evading the

requirements of these laws. This is true of the

case of Ray vs. Donnell and

Hamilton, which was tried before the United States

Circuit Court in Indiana, at the May term, 1849. A

slave woman, Caroline, and her four children fled

from Kemble County, Kentucky, and found shelter in a

barn near Clarksburg, Indiana. Here they were

discovered by Woodson Clark, a farmer

living in the neighborhood, who took measures

immediately to inform their master, while the slaves

were removed to a fodder-house for safe-keeping.

In some way Messrs. Donnell and

Hamilton learned of the capture of the negroes by

Mr. Clark, and secured a writ of habeas

corpus in their behalf; but, if the testimony of Mr.

Clark's son, supported by certain circumstantial

evidence, is to be credited, the blacks were released

from custody by the personal efforts of the defendants,

and not by legal process. Considerable evidence

conflicting with that just mentioned appears to have

---------------

10 Law Reporter, 395 ; s. c. 5 Western Law

Journal, 206; 7 Federal Cases, 1093; for the

third trial (1849), see 5 McLean's Reports, 64;

s. c. 7 Western

Law Journal, 222; 7 Federal Cases, 1095.

See also The Firelands Pioneer, July, 1888, pp.

41,42.

1 5 Illinois Reports, 498-618; 14

Howard's Reports, 13, 14.

[Pg. 279] - PENALTIES

FOR AIDING FUGITIVES

had little weight with

the jury, for it gave a verdict for the claimant and

assessed his damages at $1,500.1

In the trial of Mitchell, an abolitionist of the

town of Indiana, Pennsylvania, in 1853, for harboring

two fugitives, some of the evidence was intended to show

that he was connected with a "regularly organized

association," the business of which was "to entice

negroes from their owners, and to aid them in escaping

to the North." The slaves he was charged with

harboring had been given employment on his farm in the

country, where, as it was thought, they would be secure.

After remaining about four months they were apprised of

danger and escaped. Justice Grier charged

the jury to "let no morbid sympathy, no false respect

for pretended 'rights of conscience,' prevent it from

judging the defendant justly." A verdict of $500

was found for the plaintiff.2

Penalties for hindering the arrest of a fugitive slave

were imposed in two other noted cases, which deserve

mention here, although they are considered at length in

another connection. One of these was Booth's

case, with which the Supreme Court of Wisconsin, and the

Distinct and Supreme Courts of the United States dealt

between the years 1855 and 1858. The sentence

pronounced against Mr. Booth included

imprisonment for one month and a fine of $1,000 and

costs - $1,451 in all.3 The other case

was what is commonly known as the Oberlin-Wellington

case, tried in the United States District Court at

Cleveland, Ohio, in 1858 and 1859. Only two out of

the thirty-seven men indicted were convicted, and the

sentences imposed were comparatively light. Mr.

Bushnell was sentenced to pay a fine of $600 and

costs and to be imprisoned in the county jail for sixty

days, while the sentence of the colored man, Langston,

was a fine of $100 and costs and imprisonment for twenty

days.

In all of the cases thus far considered the charges

upon which the transgressors of the Fugitive Slave laws

were

---------------

1 4 McLean's Reports, 504-515

2 2 Wallace, Jr.'s Reports, 313,

317-323

3 21 Howard's Reports, 510; The

Fugitive Slave Law in Wisconsin, with Reference to

Nullification Sentiment, by Vroman Mason, p. 134.

[Pg. 280]

prosecuted were, in general terms, harboring and

concealing runaways, obstructing their arrest, or aiding

in their rescue. There was, however, one case in

which the crime alleged in the indictment was much more

serious, being nothing less than treason against the

United States. This was the famous Christiana

case, marked not only by the nature of the indictment,

but by the organized resistance to arrest made by the

slaves and their friends, and by the violent death of

one of the attacking party. The frequent abduction

of negroes from the neighborhood of Christiana, in

southeastern Pennsylvania, seems to have given occasion

for the formation, about 1851, of a league for

self-protection among the many colored persons living in

that region.1 The leading spirit in

this association was William Parker, a

fugitive slave whose house was a refuge for other

runaways. On September 10, Parker and his

neighbors received word from the Vigilance Committee of

Philadelphia that Gorsuch, a slaveholder of

Maryland, had procured warrants for the arrest of two of

his slaves, known to be staying at Parker's

house. When, therefore, Gorsuch with his

son and some friends appeared upon the scene about

daybreak on the morning of the 11th, and, having broken

into the house, demanded the fugitives, the negroes lost

little time in sounding a horn from one of the

upper-story windows to summon their friends. From

fifty to one hundred men, armed with guns, clubs and

corn-cutters, soon came up. Castner

Hanway and Elijah Lewis, two Quakers,

who had been drawn to the place by the disturbance,

declined to join the marshal's posse and help arrest the

slaves; but they advised the negroes against resisting

the law, and warned Gorsuch and his party to

depart if they would prevent bloodshed. Neither

side would yield, and a fight was soon in progress.

In the course of the conflict the slave-owner was

killed, his son severely wounded, and the fugitives

managed to escape.

The excitement caused by this affair extended

throughout the country. The President of the

United States placed a company of forty-five marines at

the disposal of the United

---------------

1 Smedley, Underground Railroad,

pp. 107, 108 ; 2 Wallace Jr.'s Reports, 159.

[Pg. 281] - CHRISTIANA

CASE, 1854

States marshal, and these

proceeded under orders to the place of the riot. A

large number of police and special constables made

search far and wide for those concerned in the rescue.

Their efforts were rewarded with the arrest of

thirty-five negroes and three Quakers, among the latter

Hanway and Lewis, who gave themselves up.

The prisoners were taken to Philadelphia and indicted by

the grand jury for treason. Hanway was

tried before the Circuit Court of the United States for

the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in November and

December, 1851. In the trial it was shown by the

defence that Mr. Hanway was a native of a

Southern state, had lived long in the South, and, during

his three years' residence in Pennsylvania, had kept

aloof from anti-slavery organizations and meetings; his

presence at the riot was proved to be accidental.

Under these circumstances the charge of Justice

Grier to the jury was a demonstration of the

unsoundness of the indictment: the judge asked the jury

to observe that a conspiracy to be classed as an act of

treason must have been for the purpose of effecting

something of a public nature ; and that the efforts of a

band of fugitive slaves in opposition to the capture of

any of their number, even though they were directed by

friends and went the full length of committing murder

upon their pursuers, was altogether for a private

object, and could not be called "levying war" against

the nation. It did not take the jury long to

decide the case. After an absence of twenty

minutes the verdict "not guilty" was returned. One of

the negroes was also tried, but not convicted.

Afterward a bill was brought against Hanway and

Lewis for riot and murder, but the grand jury

ignored it, and further prosecution was dropped.1

One cannot examine the records of the various cases

that have been passed in review in the preceding pages

of this chapter without being struck in many instances

by the character of the men that served as counsel for

fugitive slaves and

---------------

1 Still's Underground Railroad Records,

pp. 348-368; Smedley, Underground Railroad,

pp. 107-130; 2 Wallace Jr.'s Reports, pp.

134-206;

M. G. McDougall, Fugitive Slaves, pp. 50,

51; Wilson, Rise and Fall of the

Slave Power, Vol. H, pp. 328, 329.

[Pg. 282]

their friends. It not infrequently happens that

one comes upon the name of a man whose principles,

ability and eloquence won for him in later years

positions of distinction and influence at the bar and in

public life. In the Christiana case, for example,

Thaddeus Stevens was a prominent figure; in the

Van Zandt case Salmon P. Chase and William H.

Seward presented the arguments against the Fugitive

Slave Law before the United States Supreme Court;1

Mr. Chase also appeared in Eells' case and

in the case known as ex parte Robinson,

besides others of less judicial importance. Rutherford

B. Hayes took part in a number of fugitive slave

cases in Cincinnati, Ohio. A letter written by the

ex-President in 1892 says: "As a young lawyer, from the

passage of the Fugitive Slave Law until the war, I was

engaged in slave cases for the fugitives, having an

understanding with Levi Coffin and other

directors and officers the U. R.

R. that my services would be freely give."2

John Jolliffe, another lawyer of Cincinnati, less

known than the antislavery advocates already mentioned,

was sometimes associated with Chase and Hayes

in pleading the cause of fugitives.3

The Western Reserve was not without its members of the

bar that were ready to display their legal talent in a

movement well grounded in the popular mind of eastern

Ohio. An illustration is afforded by the

trial of the Oberlin-Wellington rescuers, when four

eminent attorneys of Cleveland offered their services

for the defence, declining at the same time to accept a

fee. The vent shows that the political aspirations

of these men were not injured by their procedure, for

Mr. Albert G. Riddle, who spoke first for the

defence, was elected to Congress from the Cleveland

district the following year, and Mr. Rufus P.

Spalding, one of his associates, was similarly

honored by the same district in 1862.4

In November, 1852, the legal firm of William H. west

and James Walker, of Bellefontaine, Ohio,

attempted to release from custody several

---------------

1. Wilson, Rise and Fall of the Slave

Power, Vol. I, p. 477.

2. Letter of Mr. Hayes, Fremont, O., Aug. 4,

1892.

3. Reminiscences of Levi Coffin, pp.

548, 549.

4. Rhodes, History of the United States,

Vol. II, p. 364. The others representing the

rescuers were Franklin T. Backus and Seneca O. Griswold.

See bJ. R. Shiperd's History of the

Oberlin-Wellington Rescue,p. 14.

[Pg. 283] - COUNSEL

FOR FUGITIVE SLAVES

negroes belonging to the

Piatt family of Kentucky, before their claimants could

arrive to prove property. The attempt was

successful, and, by prearrangement, the fugitives were

taken into a carriage and driven rapidly to a

neighboring station of the Underground Railroad.

The funds to pay the sheriff, the court expenses and the

livery hire were borne in part by Messrs. West and

Walker.1

Among the names of the legal opponents of fugitive

slave legislation in Massachusetts, that of Josiah

Quincy, who gained distinction in public life and

as President of Harvard College, is first to be noted.

Mr. Quincy was counsel for the alleged

runaway in one of the earliest cases arising under the

act of 1793.2 In some of the well-known

cases that were tried under the later act Richard H.

Dana, Robert Rantoul, Jr., Ellis Gray Loring, Samuel E.

Sewell and Charles G. Davis appeared for the

defence. Sims' case was conducted by

Robert Rantoul, Jr., and Mr. Sewell;

Shadrach's by Messrs. Davis,

Sewell and Loring; and Burns' case by

Mr. Dana and others.3

Instances gathered from

other Northern states seem to indicate that information

of arrests under the Fugitive Slave acts almost

invariably called out some volunteer to use his legal

knowledge and skill in behalf of the accused, and that

in many centres there were not lacking men of

professional standing ready to give their best efforts

under circumstances that promised, in general, little

but defeat. Owen Lovejoy, of

Princeton, Illinois, was arrested on one occasion for

aiding fugitive slaves, and was defended by James H.

Collins, a well-known attorney of Chicago.

Returning from the trial of Lovejoy, Mr.

Collins learned of the arrest of Deacon

Gushing, of Will County, on a similar charge, and

together with John M. Wilson he immediately

volunteered to conduct the new case.4

At the hearing of Jim Gray, a runaway from

Missouri, held before Judge Caton of the

State Supreme Court at Ottawa, Illinois, Judge E. S.

Leland, B. C. Cook,

---------------

1 Conversion

with Judge William H. West, Bellefontaine, O.,

Aug. 11, 1894.

2 M. G. McDougall, Fugitive

Slaves, p. 35.

3 Ibid., pp. 44, 46, 47.

4 G. H. Woodruff, History of Will

County, Illinois, p. 264.

[Pg. 284] -

O. C. Gray and J. O. Glover appeared

voluntarily as counsel for the negro.1

As a result of the hearing it was decided by the court

that the arrest was illegal, since it had been made

under the state law; the negro was, therefore,

discharged from the arrest, but could not be released by

the judge from the custody of the United States marshal.

However, the bondman was rescued, and thus escaped.