|

CHAPTER XI. -

EFFECT OF THE UNDERGROUND

RAILROAD

Pg. 340 -

THE Underground Road as a subject for

research - Obscurity of the subject - Books dealing with

the subject

Magazine articles on the Underground Railroad -

Newspaper articles on the subject

Scarcity of contemporaneous documents - Reminiscences

the chief source - The value of reminiscences

illustrated

THE effect of Underground

Railroad operations in steadily withdrawing from the

South some of its property and thus causing constant

irritation to slave-owners and slave-traders has already

been commented upon. The persons losing slaves of

course regarded their losses as a personal and

undeserved misfortune. Yet, considering the

question broadly from the standpo9int of their own

interests, the work of the underground system was a

relief to the masters and to the South. The

possibility of a servile insurrection was a dreadful

thing for Southern minds to contemplate; but they could

not easily dismiss the terrible scenes enacted in San

Domingo during the yeas 1791 to 1793 and the three

famous uprisings of 1800, 1820 and 1831, in South

Carolina and Virginia. The Underground Railroad

had among its passengers such persons as Josiah

Henson, J. W. Loguen, Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman,

William Wells Brown and Henry Bibb; it

therefore furnished the means of escape for persons well

qualified for leadership among the slaves, and thereby

lessened the danger of an uprising of the blacks against

their masters. The negro historian, Williams,

has said of the Underground Road that it served as a

"safety-valve to the institution of slavery. As

soon as leaders arose among the slaves, who refused to

endure the yoke, they would go North. Had they

remained there must have been enacted at the South the

direful scenes of San Domingo."1

It is difficult to arrive at any satisfactory idea of

the actual loss sustained by slave-owners through

underground channels. The charges of bad faith

against the free states made in Congress by Southern

members where sometimes accompanied

---------------

1 History of the Negro Race in America, Vol II,

pp. 58, 59 [Page 341] - LOSS

SUSTAINED BY SLAVE-OWNERS -

by estimates of the amount of human property lost on

account of the indisposition of those living north of

Mason and Dixon's line to meet the requirements of the

fugitive slave legislation. Thus as early as 1822,

Moore, of Virginia, speaking in the House in favor of a

new fugitie recovery law, said that the district he

represented lost four or five thousand dollars worth of

runaway slaves annually.1 In August,

1850, Atchison, of Kentucky, informed the Senate that

"depredations to the amount of hundreds of thousands of

dollars are committed upon the property of the people of

the border slave states of this Union annually."2

Pratt of Maryland, said that not less than

$80,000 worth of slaves was lost every year b citizens

of this state.3 Mason, of

Virginia, declared that the losses of ihs state were

already too heavy to be borne, that they were increasing

from year to year, and were then in excess of $100,000

per year.4 Butler, of South

Carolina, reckoned the annual loss of the Southern

section at $200,000.5 Clingman,

of North Carolina, said that the thirty thousand

fugitives then reported to be living in the North were

worth at current prices little less than $15,000,000.6

Claiborne, the biographer of General John A.

Quitman, who was at one time governor of Louisiana,

indicated as one of the defects of the second Fugitive

Slave Law its failure to make "provision for the

restitution to the South of the $30,000,000, of which

she had been plundered through the 100,000 slaves

abducted from her in the course of the last forty years"

(1810-1850);7 and the same writer stated that

slavery was rapidly disappearing from the District of

Columbia at the time of the enactment of the new law,

the number of slaves "having been reduced since 1840

form ---------------

1 Benton's Abridgment of the Debates of Congress,

Vol. VII, p. 296.

2 Congressional Glove, Thirty-first Congress,

First Session, Appendix, p. 1601.

3 Ibid., p. 1603.

4 Ibid., p. 1606.

5 Von Holst, Constitutional and Political History of

the United States, Vol. III, p. 552.

6 Congressional Globe, Thirty-first Congress,

First Session, p. 202. See also Von Holst's work,

Vol. III, p. 552, foot-note.

7 J. F. H. Caliborne, Life and Correspondence of

John A. Quitman,Vol. II, p. 28.

[Page 342]

4,694 to 650, by 'underground railroads' and felonious

abductions."1

The wide divergences among the estimates here given, as

well as the obvious difficulty of getting reliable

information in regard to the number of runaway slaves,

renders these figures of little use in determining the

loss of human property by the slaveholding states.

Nevertheless, the estimates are valuable in illustrating

the character of the complaints that were made in

Congress, and in enabling one to realize that the tenure

of slave property in the border states was rendered

precarious by the operations of the Underground

Railroad. Can it be thought strange that the

disappearance week by week and month by month of

valuable slaves over the unknown routes of the

underground system should have produced wrath, suspicion

and hostility in the minds of people who could justly

claim to have a constitutional guarantee, the laws of

Congress, and the decisions of the highest courts on

their side?

In the compendiums of the United States Census for 1850

and 1860 are some statistics on fugitive slaves, which

fall far short of the most moderate estimates of the

Southerners, and flatly disagree with the testimony

gathered from all other quarters. The official

reports appear to show that the number of slaves

escaping from their masters was small and

inconsiderable, that it rapidly decreased, and that it

was independent of proximity to a free population.

But the censuses are not only opposed to the evidence,

they are on their face inadequate.

If, as those tables indicate, only 1,011 slaves escaped

from

their masters in 1850, and only 803 in 1860, and in the

latter year only 500 escaped from the border slave

states, then it becomes impossible to understand the

emphasis laid by Southern men upon the value of their

runaway slaves, the steady pressure made by the border

states for a more stringent law that resulted in the

Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, and the allegation of bad

faith on the part of the North put

---------------

1 J. F. H. Claiborne, Life and

Correspondence of John A. Quitman, Vol. II,

p. 30. His figures are, of course, of not correct.

[Pg. 343] - CENSUS REPORTS ON FUGITIVE

SLAVES -

forth by the Southern states as a reason for secession.1

In considering the weight to be ascribed to the figures

on fugitive slaves supplied by the census compendiums,

it is proper to set over against them the showing

afforded by the same compendiums relative to the decline

of the slave population in the border slave states

during the decade 1850-1860;for it is to be noted that

the compendiums show a marked decline in these states,

that they show a greater percentage of decline in the

northernmost counties of these states than in the states

as a whole, and, what is even more remarkable, that the

loss appears to have been still greater during this time

in the four "pan-handle" counties of Virginia than in

any of the other states referred to, or in the border

counties of any one of them.2 It can

scarcely be suggested that the relatively rapid decline

of the slave population in the border counties was due

to larger shipments of slaves to the far South from

these marginal regions without at the same time

suggesting that the explanation for such shipments lay

in the proximity of a free population and the numerous

lines of Underground Railroad maintained by it.

The concurrence of evidence from sources other than the

census reports, and the agreement therewith of part of

the evidence gathered from these reports themselves,

constrains one to say that those who compiled the

statistics on fugitive slaves did not secure the facts

in full; and that the complaints of large losses

sustained by slave-owners through the befriending of

fugitive slaves by Northern people, frequently made by

Southern representatives in Congress and by the South

generally, were not without sufficient foundation.

It is natural that there should be great variation

among the guesses made as to the total number of those

indebted for liberty to the Underground Road. Very

few of the persons that harbored runaways were so

indiscreet as to keep a register of their hunted

visitors. The hospitality was equal to all

possible demands, but was kept strictly secret.

Under these circumstances one should handle all

numerical generalizations with caution.

---------------

1 Census of 1860, pp. 11, 12. See Tale

A, Appendix C, p. 378.

2 See Tables B and C, Appendix C, p. 379.

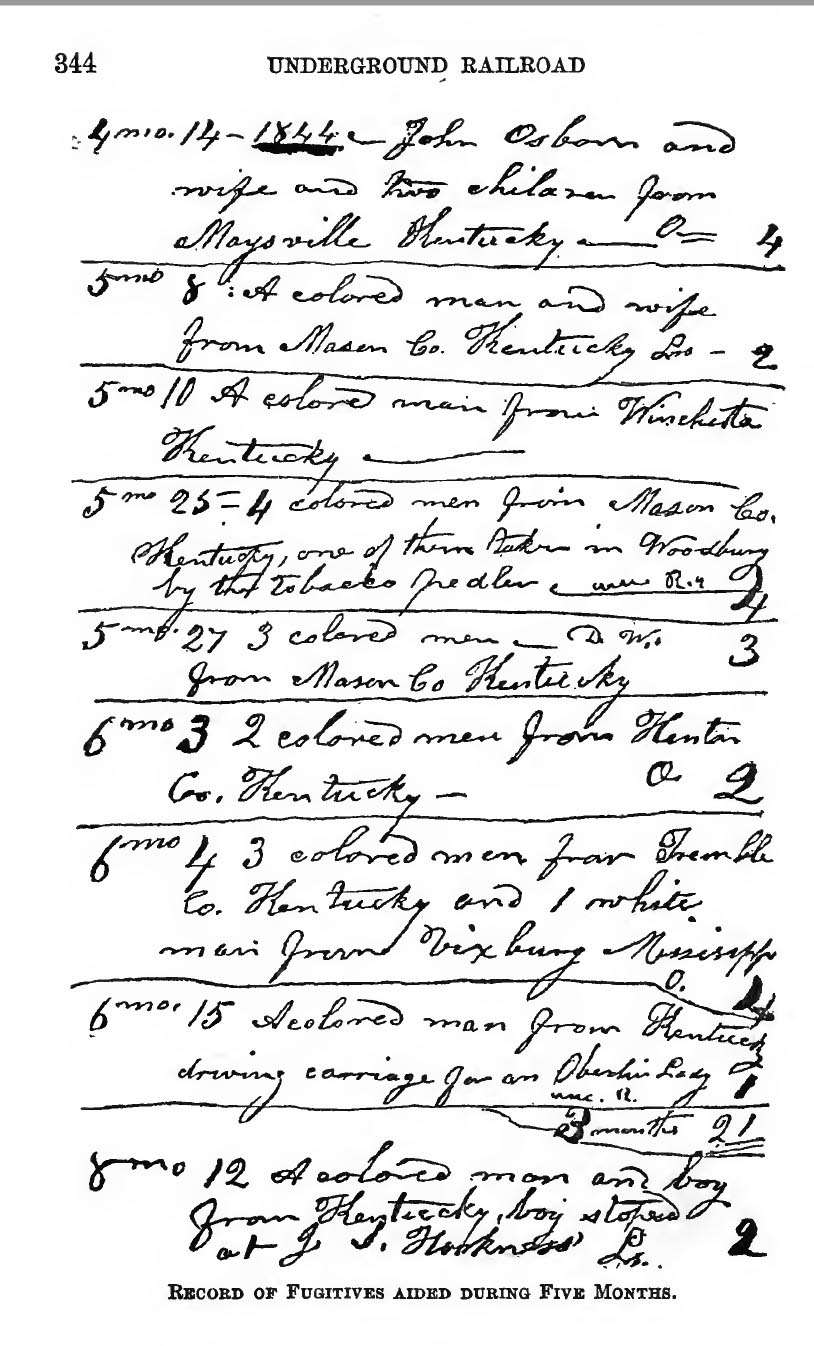

[Pg. 344]

Record of Fugitives Aided During Five Months.

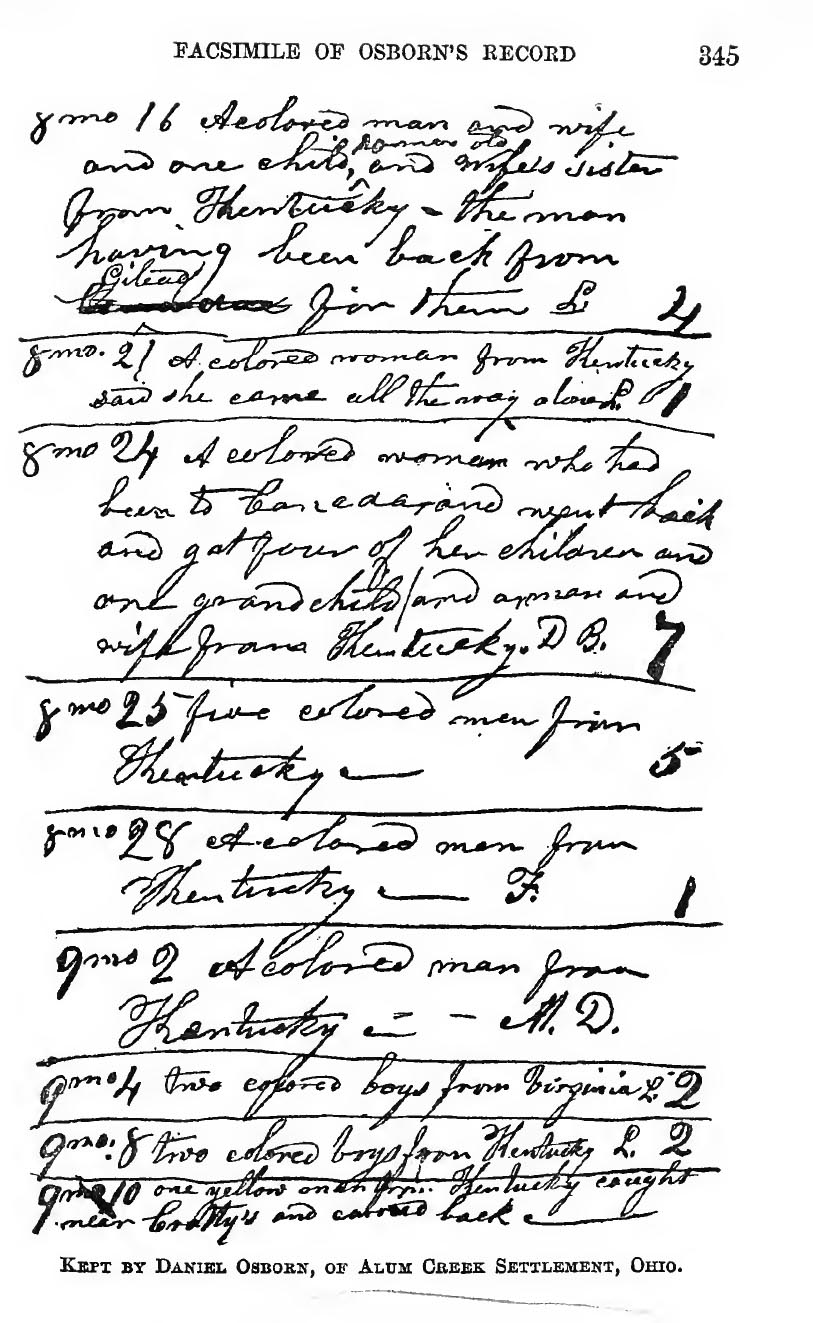

[Pg. 345] - FACSIMILEOF OSBORN'S

RECORD

Kept by Daniel Osborn, of Alum Creek Settlement, Ohio.

[Pg. 346]

By rare good fortune the writer has found a single leaf

of a diary kept by Daniel Osborn, a Friend or

Quaker, of Alum Creek Settlement, Delaware County, Ohio,

which gives a record of the blacks passing through that

neighborhood during an interval of five months, from

April 14 to Sept. 10, 1844. The accompanying

facsimiles, which reproduce the two sides of the leaf,

show that the number is forty-seven. The year in

which this memorandum was made may be fairly taken as a

average year, and the line on which this Quaker

settlement was a station as a representative underground

route in Ohio. Now, along Ohio's southern boundary

there were the initial stations of at least twelve

important lines of travel, some of which were certainly

in operation before 1830. Let us consider, as we

may properly, that the period of operation continued

from 1830 to 1860. Taking these as the elements

for a computation, one may reckon that Ohio may have

aided not less than 40,000 fugitives in the thirty years

included in our reckoning.1 That the number

of refugees after 1844 did not decrease is indicated by

the statement that during one month in the year of

1854-1855 sixty were harbored by one member of the Alum

Creek Settlement. It is to be remembered that

several families of the settlement were engaged in this

work.2

An illustration of

underground activity in the East may be ventured. Mr.

Robert Purvis, of Philadelphia, states that he kept

a record of the fugitives that passed through the hands

of the Vigilance Committee of Philadelphia for a long

period, till the trepidation of his family after the

passage of the Fugitive Slave Bill in 1850 caused him to

destroy it. His record book showed, he says, an

average of one a day sent northward. In other

words, between 1830 and 1860 over 9,000 runaways were

aided in Philadelphia. But we know that the

Vigilance Committee did not begin this sort of work in

the Quaker City, and that underground activities there

date back at least to the time of Isaac T. Hopper’s

earliest efforts, that ---------------

1 This computation was first printed by the

writer in the American Historical Review, April,

1896, pp. 462, 463.

2 Conversation with M. J. Benedict,

L. A. Benedict and others, Alum Creek Settlement,

Ohio, Dec. 2, 1893. [Pg. 347] -

DRAIN ON RESOURCES OF LAWRENCE DEPOT -

is, 1800 and before. We also know that there were

many centres round about Philadelphia, some of whose

work was certainly done independently of that place.

That the resources of some of the operators in centres

in the West were being drained almost to exhaustion by

the demands of the heavy traffic towards the close of

the underground period, distinctly appears in the

following letter from Col. J. Bowles, of

Lawrence, Kansas, to Mr. F. B. Sanborn:—

LAWRENCE April 4th, 1859

MR. F. B. SANBOURN

Dear Sir at the suggestion of friend Judge Conway

I address you these few hastily written lines. I

see I am expected to give you some information as to the

present condition of the U. G. R. R. in Kansas or

more particularly at the Lawrence depot. In ofrer

that you may fully understand the present condition of

affairs I shall ask your permission to relate a small

bit of the early history of this, the only paying, R. R.

in Kansas.

Lawrence has been (from the first settlement of Kansas)

known and cursed by all slave holders in and out of Mo.

for being an abolition town. Missourians have a

peculiar faculty for embracing every opportunity to

denounce, curse, and blow every thing they

dislike. This peculiar faculty of theirs gave

Lawrence great notoriety in Mo. especially among

the negroes to whom the principal part of their

denunciations were directed and on whom they were

intended to have great effect. I have learned from

negroes who were emigrating from Mo. that they never

would have known anything about a land of freedom or

that they had a friend in the world only from their

master’s continual abuse of the Lawrence abolits.

Slaves are usually very cunning and believe about as

much as they please of what the master is telling him (thoug

of course he must affect to believe every word) knowing

it is to the master’s interest to keep him ignorant of

every thing that would make him likely or even wish to

be free.

One old fellow said “when he started to come to

Lawrence he didn’t know if all de peoples in disha town

war debbils as ole massa had said or not, but dis he did

know if he could get dar safe old massa was fraid to

come arter him, and if dey all should prove to be bad as

ole massa had said he could lib wid dem bout as well as

at home.” Some few of them were unavoidably taken

[Pg. 348]

back to Mo. after leaving here for Iowa. Many of

them found an opportunity to make their escape and bring

others with them and none ever failed to be a successful

missionary in the cause, telling every one he had a

chance to converse with of the land of freedom, and the

friends he found in Lawrence. One man I know well

who has been captured twice and was shot each time in

resisting his captors (one of whom he killed) told me

that he was confident he had assisted in the escape of

no less than twenty five of his fellow beings, and that

he had also given information or sown the seed that

would make a hundred more free men. He is now with

some others in or about Canada. The last and

successful escape was made from western Texas where he

was sent for safe keeping. You can see from the

above why L_____ has had more than would seem to be her

share of this good work to do. At first our means

were limited and of course could not do much but then we

were not so extensively known or patronized. As

our means increased we found a corresponding increase in

opportunity for doing good to the white man as well as

the black. Kansas has been preeminently a land of

charity. The friends in the East have helped such

objects liberally yet Kansas has had much to do for

herself in that line. To give you an idea of what

has been done by the people of this place in U. G. R. R.

I’ll make a statement of the number of fugitives who

have found assistance here. In the last four years

I am personally known to [cognizant of] the fact of

nearly three hundred fugitives having passed through and

received assistance from the abolitionists here at

Lawrence. Thus you see we have been continually

strained to meet the heavy demands that were almost

daily made upon us to carry on this (not very)

gradual emancipation. I usually have assisted

in collecting or begging money for the needy of either

class. Many of the most zealous in the cause of

humanity complained (as they had good cause to) that

this heavy (and continually increasing) tax was

interfering with their business to such a degree that

they could not stand it longer and that other provisions

must be made by which they would be relieved of a

portion of a burden they had long bourn. This was

about the state of affairs last Christmas when as you

are aware the slaves have a few days holiday. Many

of them chose this occasion to make a visit to Lawrence

and during the week some twenty four came to our town,

five or six of the number brought means to assist them

on their journey. These were sent on but the

remainder must be kept until money could be raised to

send them on. $150 [Pg.

349] - DRAIN ON RESOURCES OF LAWRENCE DEPOT -

was the ain’t necessary to send them to a place of

safety. Under the circumstances it necessarily

took some time to raise that am’t, and a great many

persons had to be applied to. It was not enough

that the sympathies and love for the cause of humanity

was appealed to in order to raise money, many had to be

argued with and shown that the cause was actually in a

suffering condition and the fugitives were then in town

and the number must also be made known in order that the

person might give liberally. Lawrence like most

all towns has her bad men pimps and worst of all a few

democrats, all of whom will do anything for money.

Somewhere in the ranks of the intimate friends to the

cause these traitors to God and humanity found a judas

who for thirty pieces of silver did betray our cause.

This was not suspected until after the capture of Ur

Day. . . . Every thing goes to prove that the

capture of Day’s party was the work of a traitor who

though suspected has not yet been fairly tried and dealt

with as will be done as soon as Day is bailed out which

will be done [in] a few days.

* * *

* * * *

* * We would like .

. . that you plead our cause with those of our friends

who are disposed to censure us and convince them we are

still worthy and in great need of their respect and

cooperation. I am sorry to say (but tis true) that

many of the most zealous in the cause of humanity have

become somewhat discouraged by the hard times and the

lamentable capture of Day and party and cannot be

induced to take hold of it and lend a willing hand.

Never the less the work has went slowly but surely on,

until very recently. Those who have

persevered like many others, have found their bottom

dollar also of the money so generously contributed by

persons of your notable society. This is partialy

owing to heavy expenses of the trial of Dr Day

and son which has been principally borne by the society

here and has amounted to near $300. Now seems to

be our dark day and we are casting about to see what can

be done. We have some eight or ten fugitives now

on hand who cannot be sent off until we get an addition

to our financial department. This statement of

facts has been made with a full knowledge of the many

calls that is made upon your generosity in that quarter.

Nothing shall be urged as an alternative for we feel

confident the case here presented will meet with merited

assistance sympathy or advice, as you may deem best.

One word of old Brown and his movement in the

emancipation cause, and I will have done. I

understand from [Pg. 350]

some parties who have been corresponding with some

persons in Boston and other places in behalf of our

cause that we could and would receive material aid only

they are holding themselves in readiness to assist

Brown. Such men I honor and they show themselves

worthy the highest regard yet I assure them they do not

understand Brown’s plans for carrying out his

cause. I have known Brown nearly four

years, he is a bold cool calculating and far seeing man

who is as consciencious as he is smart. He “knows

the right and dare maintain it.” I have talked

confidentially with him on the subject. I know he

expressed himself in this way as to the effects that he

intended to make the master pay the way of the slave to

the land of freedom. That is he intended to take

property enough with the slaves to pay all expenses.

So you see there is not fear of a large demand from that

quarter. By no means would I be understood as

counciling not to assist him. No indeed if I

counciled at all it would be to this effect, render him

all the assistance he ever asks for he is worthy and his

cause is a good one. Others would have been

with him only they had all they could do in another

quarter. I feel myself highly honored to be placed

where I can with propriety communicate with a society

whom I have only known to admire. Hoping what I

have written (disconnectedly and badly written as it is)

may be acceptable and that I may hear from you soon.

I am very respectfully Your obedient servant

J. BOWLES

Lawrence

F. B. SANBOURN

Concord.

The success of the Underground Road in transporting

negroes beyond the limits of the Southern states was

long ago commented upon as standing in marked contrast

with that of the American Colonization Society.

This association was organized in 1816 and soon had

auxiliary societies in most of the states. Its

object was to remove the free blacks and such as might

be made free from the South, and colonize them on the

coast of Africa. By 1857, after an existence of

forty years, the Colonization Society had sent to Africa

9,502 emigrants, of whom 3,676 were free-born, 326

self-purchased, and 5,500 emancipated on condition of

being transported. That the informal method of the

abolitionists was many times as efficient as that

adopted by the organization mentioned,

[Pg. 351] - ACCUSATIONS MADE BY

SOUTHERN STATES -

with its treasury and its board of officers, cannot be

denied.1

It is not surprising that the secret enterprises of

this determined class of people - so effectual as to

make rare the pursuit of a fugitive during the last

years of the decade preceding the War2 -

should have become the ground of an important charge

against the North in the crisis of 1860. The

violation of the Fugitive Slave Law was an accusation

upon which Southern members of Congress rang all the

changes in the course of the violent debates of the

sessions of 1860-1861. Thus Jones, of

Georgia, said in the House in April, 1860: "It is a

notorious fact that in a good many of the non-slaving

holding states the Republican party have regularly

organized societies - underground railroads - for the

avowed purpose of stealing the slaves from the border

States, and carrying them off to a free State or to

Canada. These predatory hands are kept up by

private and public subscriptions among the

Abolitionists; and in many of the States, I am sorry to

say, they receive the sanction and protection of the

law. The border States lose annually thousands and

millions of collars' worth of property by this system of

larceny that has been carried on for years."

Polk of Missouri, whose state had suffered not a

little through the flight and abduction of slaves, made

the same complaint in the Senate in January, 1861:

"Underground railroads are established," said he,

"stretching from the remotest slaveholding States clear

up ---------------

1 E. M. Pettit, Sketches in the

History of the Underground Railroad, Introduction,

p. xi. Wilson gives an account of the

American Colonization Society in his Rise and Fall of

the Slave Power, Vol. I, pp. 208-222; see also the

Life of Garrison, by his children, Index.

2 McDougall, Fugitive Slaves,

p. 71. [Pg. 352]

to Canada. Secret agencies are put to work in the

very midst of our slaveholding communities to steal away

slaves. The constitutional obligation for the

rendition of the fugitive from service is violated.

The laws of Congress enacted to carry this provision of

the Constitution into effect are not executed.

Their execution is prevented. Prevented, first, by

hostile and unconstitutional state legislation.

Secondly, by a vitiated public sentiment. Thirdly,

by the concealing of the slave, so that the United

States law cannot be made to reach him. And when

the runaway is arrested under the fugitive slave law -

which, however, is seldom the ase - he is very often

rescued . . . . This lawlessness is felt with

special seriousness in the border slave States.

The underground railroads start mostly from these

States. Hundreds of thousands of dollars are lost

annually. And no State loses more heavily than my

own. Kentucky, it is estimated, loses annually as

much as $200,000. The other border States no doubt

lose in the same ratio, Missouri much more.

But all these losses and outrages, all this disregard of

constitutional obligation and social duty, are as

nothing in their bearing upon the Union in comparison

with the animus, the intent and purpose of which they

are at once the fruit and the evidence. . . .” 1

Of this animus the election of Lincoln was

regarded as the crowning proof; and it became, as is

well known, the signal for secession.

In December, 1860, the very month in which South

Carolina chose to withdraw from the Union, the arrest of

a runaway negro in Canada gave rise to an extradition

case that became an additional cause of excitement.

The negro was William Anderson who in 1853 had

been caught without a pass in Missouri, and had killed

the man that tried to capture him. In 1860 he was

recognized in Canada by a slave-catcher from Missouri,

was arrested on the charge of murder, and thrown into

jail at Toronto. As the Ashburton treaty contained

an article providing for the extradition of slaves

guilty of crimes committed in the United States, the

American government sought to secure the surrender of

-----

1 Congressional Globe, Thirty-sixth

Congress, Second Session, p. 356; see also ibid.,

Appendix, p. 197. [Pg. 353] -

EXTRADITION OF ANDERSON REFUSED -

Anderson for punishment. Lord Elgin,

Governor-General of Canada at the time, was appealed to

in the fugitive’s behalf by Mrs. Laura S. Haviland.

He made a spirited reply to the effect that “in case of

a demand for William Anderson, he should

require the case to be tried in their British court; and

if twelve freeholders should testify that he had been a

man of integrity since his arrival in their dominion, it

should clear him.” Nevertheless, the case was

twice decided against the defendant, first by the common

magistrate’s court, then by the Court of Error and

Appeal, to which it had been carried on a writ of habeas

corpus. But this did not end the matter.

Through the efforts of the fugitive’s friends

application was made for a writ of habeas corpus to the

English Court of the Queen’s Bench, and the writ was

granted. Anderson was defended by Gerrit

Smith, whose eloquent speech produced a profound

impression in Canada, and did not fail to attract

considerable notice in all parts of the United States.1

During the month of December, in which the Anderson

case came into prominence, the example of secession set

by South Carolina was followed by five other cotton

states. Meantime Congress was giving unmistakable

evidence of the importance attaching to the fugitive

slave question. In his message of December 4,

President Buchanan gave serious consideration

to this question, although he insisted that the Fugitive

Slave Law had been duly enforced in every contested case

during his administration.2 He

recommended an “ explanatory amendment” to the

Constitution affording “recognition of the right of the

master to have his slave who has escaped from one state

to another restored and ‘delivered up’ to him, and of

the validity of the Fugitive Slave Law enacted for this

purpose, together with a declaration that all State laws

impairing or defeating this right, are violations of

---------------

1 Accounts of Anderson's case will be found

in a collection of pamphlets in the Boston Public

Library; in the Liberator, Dec. 3, 1860 and Jan. 22,

1861; in A Woman's Life Work, by Laura S.

Haviland, pp. 207, 208; in the History of Canada,

by J. M. McMullen, Vol. II, p. 259; in the History of

Canada, by John MacMullen, p. 553; and in

Fugitive Slaves, by M. G. McDougall, pp. 25,

26.

2 Journal of the Senate, Thirty-sixth

Congress, Second Session, p. 10.

[Pg. 354]

the Constitution, and are consequently null and void.”1

On December 12 not less than eleven resolutions were

introduced into the House on this subject, and on

December 13, 18 and 24 other resolutions followed.

Resolutions of a similar nature continued to be

presented in both Houses during January and February of

the succeeding year, ceasing only with the end of the

session.2

These efforts on the part of the national legislature

to appease the spirit of secession in the South were

paralleled by efforts equally futile on the part of

various Northern state legislatures during the same

period. It was reported that towards the close of

the year 1860 a caucus of governors of seven Republican

states was held in New York City, and decided to

recommend to their legislatures “the unconditional and

early repeal of the personal liberty bills passed by

their respective states.” As a matter of fact this

recommendation was made by the Republican governors of

four states, Maine, Massachusetts, New York and

Illinois, and the Democratic governors of Rhode Island

and Pennsylvania. Rhode Island repealed her

personal liberty law in January, 1861; Massachusetts

modified hers in March; and was followed by Vermont,

which took similar action in April. Ohio had

repealed her act in 1858, but her legislature seized

this opportunity to urge her sister states to cancel any

of their statutes “conflicting with or rendering less

efficient the Constitution or the laws.”3

The conciliation of the South was clearly the purpose of

these measures, but action came too late, for confidence

between the sections had already been destroyed.

The fact that the border slave states, with the

exception of Virginia, remained in the Union, must not

be interpreted as indicating small losses of human

property by these states. The strong ties existing

between the states lying on either side of the sectional

line, the presence of a rigorous Union sentiment in

Kentucky, western Virginia and the slaveholding regions

lying east and west of these, together with the hope

---------------

1 Journal of the Senate, Thirty-sixth

Congress, Second Session, p. 18.

2 For a complete list of these resolutions

see Mrs. McDougall’s monograph on

Fugitive Slaves, Appendix, pp. 117-119.

3 Rhodes, History of the United States,

Vol. Ill, pp. 262, 263. [Pg.

355] - CONCLUSION OF FUGITIVE SLAVE CONTROVERSY -

of a new compromise entertained by these states, tended

to keep them in their places in the Union. The

prospect of a stampede of slaves, in case they should

join the secession, movement, was a consideration that

may be supposed to have had some weight in fixing the

decision of the border slave states. Certainly it

was one to which Northern men attached considerable

importance at the time in explaining the steadfast

position of these states; and the impossibility of

recovering even a single fugitive from the free states

in case of a disruption of the Union along Mason and

Dixon’s line was a thing of which Southern members of

the national House were duly reminded by their Northern

colleagues.

The retention of the loyalty of the border slave states

was a matter of grave concern to President

Lincoln, who sought first of all the preservation of

the Union. In his inaugural address Lincoln had

declared his purpose to see to it that the Fugitive

Slave Law was executed, and when a few months later an

opportunity presented itself he kept his promise.

Congress also realized the need of caution on account of

the border states, and moved slowly in framing general

enactments. The changed conditions surrounding the

slaves, due to the marshalling of forces for the War and

the advance of Northern troops into the enemy’s country,

multiplied the chances for escape throughout the South,

and removed the necessity for a long and perilous

journey by the slaves to find friends. Negroes

from the plantations of both loyal and disloyal masters

flocked to the camps of Union soldiers, and could not be

separated. Under such circumstances the need of

uniformity of method in dealing with cases early became

apparent. The War had scarcely more than commenced

when protests began to be made against the employment of

Northern troops as slave-catchers. A letter read

in the Senate by Mr. Sumner, in December,

1861, made inquiry, “Shall our sons, who are offering

their lives for the preservation of our institutions, be

degraded to slave-catchers for any persons, loyal or

disloyal? If such is the policy of the government,

I shall urge my son to shed no more blood for its

preservation.”1 Two German companies in

one of the Massachusetts regi-

---------------

1 Congressional Globe, Thirty-seventh

Congress, First Session, p. 30.

[Pg. 356]

ments also entered protest, making it a condition of

their enlistment that they should not be required to

perform such discreditable service. "They

complained, and with them the German population

generally throughout the country.”1 The

inexpediency of the return of fugitives by the army was

recognized by Congress in the early part of 1862, and a

bill forbidding officers from restoring them under any

consideration was signed by the President on May 14,

1862.2

The various acts of Congress and the President relative

to fugitive slaves down to the Proclamation of

Emancipation, practically circumscribed the legal effect

of the Fugitive Slave laws to the border states, for in

the free states the laws had not been observed for a

long time. It was not until June, 1864, that these

measures were swept from the statute-book of the nation,

notwithstanding the insistence of Kentucky and the other

loyal states of the South that a constitutional

obligation rested upon the government to retain them.

The repeal act did not remove this obligation.

Such a result could come only with the extinction of

slavery, and the last vestige of slavery did not

disappear until the adoption of the Thirteenth Amendment

to the Constitution in 1865. The Amendment

provides: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,

except as a punishment for crime, whereof the party

shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the

United States or any place subject to their

jurisdiction.”

The general significance of the long controversy in

regard to fugitive slaves can best be understood by

tracing the development as a sectional issue of the

question at the bottom of it, namely, the obligation to

restore fugitives to their masters. The creation

of a line dividing the free North from the slaveholding

South in the early years of our national history, and

the enactment of the first Fugitive Slave Law, by which

the general government assumed a certain responsibility

for runaways, led to the opening of the question. From

that time ---------------

1 Congressional Globe, Thirty-seventh

Congress, First Session, p. 30; see also M. G.

McDougall's Fugitive Slaves, p. 79.

2 House Journal, Thirty-seventh

Congress, Second Session, p. 265; Senate Journal,

Thirty-seventh Congress, Secon Session, p. 285;

Congressional Globe, Thirty-seventh Congress, Second

Session, p. 1243. [Pg. 357]

on, the steadily increasing number of escapes, together

with the spread of the underground system, which made

these escapes almost uniformly successful, kept the

question open. Operations along the secret lines

constantly caused aggravation in the South; and the

pursuit of passengers, mobs and violence were results

widely witnessed in the North. The other questions

between the sections were subject to compromise, but

party action could not control the workings of the

Underground Railroad. The stirring sights and

affecting stories with which the North became acquainted

through the stealthy migration of slaves were well

adapted to make abolitionists rapidly, and the

consequence was more aggravation on both sides.

The practice of midnight emancipation in Northern states

during the early years was accompanied, not unnaturally,

with the formulation and statement of the principle of

immediatism in neighborhoods where underground methods

were familiar. Thus the way was prepared for

Garrison and his talented coworkers, whose eloquent

tongues and pens could no more be controlled by

pro-slavery forces than could the Underground Railroad

itself. Agitation reacted upon the Road and

increased its activity; this caused counter agitation by

Southerners in and out of Congress until a more rigorous

Fugitive Slave Law was secured.

The Compromise of 1850 failed to reconcile the

sections: Northern men despised the Fugitive Slave

Law, and displayed greater zeal than ever before in

aiding runaway slaves. Thus, in the later stages

of the controversy, as from its beginning, the fugitive

was a successful missionary in the cause of freedom.

Personal liberty laws were passed by the free states to

defend him; Uncle Tom's Cabin was written to

portray to the world his aspirations for liberty and his

endeavors to secure it; John Brown devised a

"subterranean pass way" to assist him, as a part of the

great scheme of liberation that failed at Harper's

ferry. One of the chief reasons for with-drawing

from the Union assigned by the seceding states was the

bad faith of the North in refusing to surrender

fugitives. At eh outbreak of the Civil War large

numbers of slaves sought refuge with the Union fores,

the government soon found it impracticable to restore

them, and disavowed all re- [Pg.

358]

sponsibility for them in 1862. By the Proclamation

of Emancipation slavery was abolished within the area of

the disloyal states, and the controversy became merely

formal, the loyal slave states striving to maintain an

abstract right based by them upon the Constitution.

In 1864, however, they were forced to yield, and the

fugitive, slave legislation was repealed. The year

following witnessed the cancellation of the fugitive

slave clause in the Constitution by the amendment of

that instrument. In view of all this it is safe to

say that the Underground Railroad was one of the

greatest forces which brought on the Civil War, and thus

destroyed slavery.

RETURN TO TABLE OF CONTENTS |