|

Until 1862

Grant township was a portion of Ross township. At

that time Ross was found to be so large as to be unweildy and so was divided, forming the new township.

The name chosen tells the sentiment of the people who

had come to that section of Vermilion County.

Loyalty to their country was expressed in choosing the

name of the hero who was conspicuous in saving that

country. The naming of this township was about the

first honor to be accorded him. This township has

never had a changed boundary. Its northern limit

is the same as the northern limit of Vermilion County,

the eastern limit that of the Indiana state line, the

southern limit, Ross township and the western boundary,

Butler township and the western boundary, Butler

township. The shape of the township is

rectangular; twelve and a half miles long by seven and

one-half miles wide. It contains 58,880 acres and

is the largest township in Vermilion County. It is

almost entirely prairie land and only had a small

portion of timber which was known as Bicknell's Point,

in about the center of the dividing line between Grant

and Ross townships. This formed the treeless

divide between the head waters of the Vermilion and

those of the Iroquois. It was late in attracting

settlement, being as late as 1860, without cultivation.

The direct road between Chicago and the south ran

directly through the center of this township, yet it was

avoided as locations for homes. Indeed, when in

1872, the railroad was surveyed through this township,

there were but few farms intersected. This stretch

of open prairie, north of Bicknell's Point, was a dread

to the benighted

traveller. The first settlements in Grant township

were made along the road stretching north from

Rossville.

An early as 1835, George and William Bicknell

took up land at Bicknell's Point which was the last

piece of timber on the route to Chicago until the valley

of the Iroquois was reached. Mr. Lockhart,

who came form Kentucky with William Newell, was

the man who first entered land north of Bicknell's

Point. Asel Gilbert entered a section of

land south of Bicknell's Point in 1838. Albert

Cumstock, B. C. Green, and James R. Stewart,

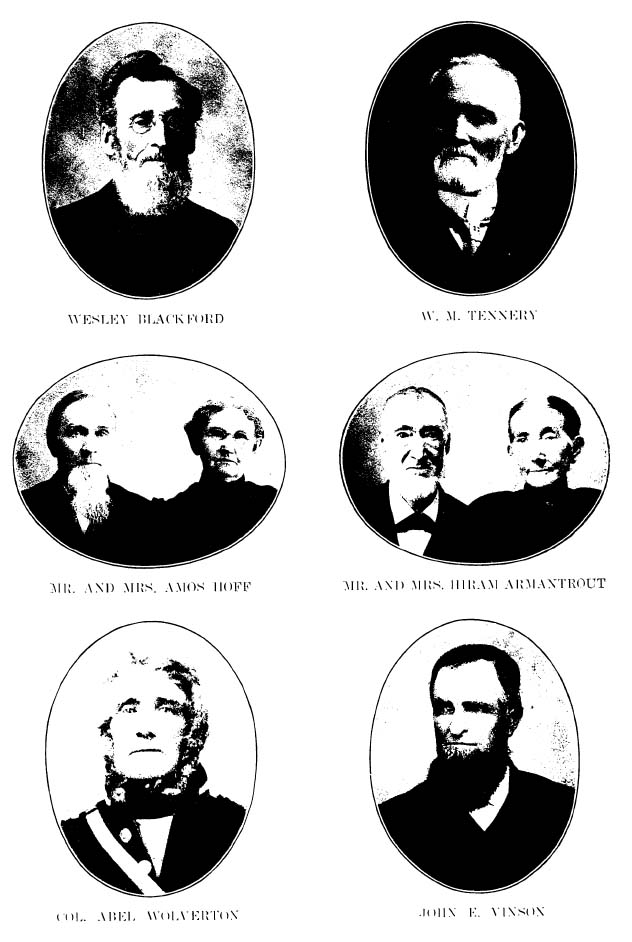

early settled near this. Col. Abel Wolverton

settled on sextion 18 in 1840, two miles

northeast of the Point. He was probably the first

settler in that neighborhood. He came from

Perrysville, Indiana. He had been in the Blackhawk

war and was as brave in fighting the hardships of the

new home in the prairie as was he in fighting the

Indians. Col. Woolverton was a competent

surveyor and his new home provided much work of this

kind. William Allen was the pioneer in the

northern part of the township. He came to Ohio in

1844. Thos. Hoopes, from whom Hoopeston was

named, came in 1855 and bought Mr. Allen's farm.

Conditions in this part of the county at this time is

pictured by Mrs. Cunningham, then a child, whose

playmates were "sky and prairie flowers in the summer

time, with the bleak cold in the winter." A

description of her experience on a night in late autumn

in this lonely place, reads: "The shadows of

declining day were creeping over the prairie landscape,

when this child, young in years but older in experience,

as were the pioneers, stood listening for a familiar

sound. The cold wind came sweeping from far over

tractless wilds, and with almost resistless force nearly

drove her to the protection of the house, yet she stood

and listened for a familiar sound, straining her ear to

catch the rumble of a wagon which told of the return of

her foster parents, who had the day before, gone to an

inland town for provisions to last them through the

coming days of winter. They had gone on this

errand some days before and were due to come back every

hour. This young girl had learned to love even

this solitude, and while she listened for the sound of

human life she noted the lull of the fierce wind, the

whirring of a flock of prairie chickens, frightened from

their accustomed haunts, fleeing by instinct to the

protection of man. Suddenly a wolf gave a sharp

bark on a distant hillside, then another, and another

and yet another answering each other from the echoing

vastness. With a shudder, not so much from fear as

from the utter lonesomeness of the time and place, she

turned and entered the house, but she could not leave

these sounds outside, she heard the mournful wail.

It is impossible to describe those sounds. So

weird, so lonely were they that the early settler

remembered them always. The lack of courage of

these animals was made up in the increased numbers they

called together, whether it was to attack the timid

prairie hen or the larger game of the open. Surely

these wolves were fit companions for the Indians.

The interior of this little house was much better

furnished than were those of the early settlers of

Vermilion County who came into other portions

twenty-five years before this time. It was easier

to transport furniture and the homes of this period were

less primitive in every way. When the girl went

into the house she found the "hired man" had milked and

was ready for his supper. He seated himself at the

kitchen stove and remarked that he did not think that

"the

[pg. 420]

folks" would come that night, as it would be very dark

and every prospect of the snowstorm, they surely would

not leave the protection of the nearest settlement to

venture on the prairie that night. The little girl

busied herself with the supper with grave misgivings

about her people, whom she earnestly hoped would venture

to come home, but whom she feared would be injured.

She could not eat and going to the window she pressed

her face to the glass and took up her silent watch.

Soon taking his candle, the hired man went to his bed,

leaving the girl to keep her watch alone. After a

little, she imagined she heard a faint sound; she ran to

the door and threw it open. As the door was flung

open their faithful shepherd dog bounded in. He

was closely followed by a number of wolves who were

chasing him and almost had caught him. They

stopped when the light from the open door fell upon

them. The girl hastily closed the door and

shutting them out shut the dog within. Then all

was silent on the prairie, except the howling of the

wind while the wolves silently slunk away in the

darkness. The girl turned to the dog and eased his

mind by a bountiful supper, when she took up her watch

once more. She hoped almost against hope as she

pressed the window pane, scanning the horizon. As

the night wore on the storm increased in violence, the

wind drove the snow in sheets of blinding swiftness,

piling it high on the window ledge, and obstructing the

view across the expanse. The wolves were silenced

by the terrible storm, but the faithful dog yet scented

them in the near neighborhood. The old clock

slowly ticked the hours away while the girl sat by the

wooden table in the center of the room with drooping

head and strained ears, until she dropped to sleep from

sheer exhaustion. Uneasy were her dreams as her

slumber was broken through discomfort and the ever

recurring growls of the dog at her feet who growled at

the scent of his pursuers. As the hours passed the

girl aroused herself and went to the window. The

storm clouds had partially cleared, and the young moon

had peeped out with a faint light. Casting her

eyes down she looked into the piercing orbs of two

wolves who were standing in the glare of the lamplight.

The girl turned to the dog and dropping beside him

buried her face in his wooly coat and bursting into

tears called out, "Taylor, what shall we do?"

With a growl and a glance toward the opening, which said

as plain as words, "I'll do all I can to protect you,"

he lay with his nose to the crack in the door. The

hours wore away and the girl and the dog watched alone

on the prairie for the coming of the human beings who

might be out on the prairie. Toward dawn the dog

sprang to her side with a low bark of delight. He

had heard and recognized the voices of his friends, and

was telling his companion that those for whom they were

keeping vigil were very near. Soon they were

housed in safety. A new day was theirs while all

the terrors of the night had been vanquished. The

sun came up, the deer were dashing from one snow bank to

another, the wolves had slunk away, the agony of the

night was passed away. Such were frequent

occurrences in the section of the country in and about

Hoopeston.

Mr. Dale Wallace, in a talk before a Hoopeston

audience, some years ago, describes that village when he

first saw it. He went to this new village on the

Illinois prairie a young man full of hope and promise.

He entered the town on the freight train of the C. D. &

V. R. R. (commonly called the "Dolly Varden") which

consisted of six gravel cars and a caboose. The

conductor stopped his

[pg. 422]

and country property. Land now worth $250 per acre

then sold for $15 to $25 per acre. Business lots

then bought for $125 some time ago, were worth $5,000.

Hoopeston gave rapidly and business enterprises kept

pace with it. About 1872,

J. S. McFerrin and Wright Chamberlain

established a bank. J. M. R. Spinning was

the first postmaster. A spirit of enterprise

pervaded every nook and corner of the hustling little

village. About every thirty days the enterprising

citizens would hold meetings and build factories and

railroads on paper. The first year of existence

Hoopeston had a circus and menagerie. This gave

the newspaper a chance to give news. Business

houses multiplied rapidly, all branches being well

represented by January, 1873. The Chronicle gave a

resume for the year, showing the erection of 180

buildings, 27 or which were business houses altogether.

The grain men brought 450,000 bushels during the year.

The freight business of the "Dolly Varden" road amounted

to 40,000. Hoopeston has had a phenomenal growth

and is a small city of beautiful homes.

<

BACK TO TABLE OF CONTENTS >

|